The Dark Horse of Innsbruck

A Büchsflinte by Any Other Name

feature By: Terry Wieland | September, 23

Having said all that, the gun itself presented several mysteries.

First, it was a hammer gun, but reportedly made around 1925, long after hammerless designs had taken over the market. Second, while its shotgun barrel was a 16 gauge, the rifle barrel was…what? The only identification was the proof house stamp of “9.3.” Okay, 9.3mm, around .366 caliber? Right. We’ll figure it out.

I will take its technical aspects one by one, but first, I want to look at where such a gun fits into the extensive, baffling pantheon of Teutonic gun designs.

Most Americans are familiar with the term Drilling, and many even refer to any multi-barreled German or Austrian gun as a drilling. This is not the case. “Drilling” is derived from the German word drei (three) and refers only to three-barreled guns. Of course, there are variations on that, too: A drilling can have two shotgun barrels and one rifle underneath (Drilling), or two rifles and one shotgun (Doppelbüchsdrilling). A double shotgun topped by a rifle barrel is a Schienendrilling.

For reasons as yet unexplained, the Büchsflinte (one rifle and one shotgun barrel, side-by-side) is often referred to as a “Cape gun.” This is British terminology, the Cape in question being that of Good Hope (South Africa). Rifle/smoothbore combination guns were popular with colonists and farmers in southern Africa because they offered versatility.

Versatility was also a major consideration for hunters in the mountains of Central Europe. To take Austria as an example, a hunter might encounter anything from a red stag to a capercaillie, to a roe deer (in the woods) or a chamois (in the high meadows.) Down below, there were wild boar and hares, to say nothing of various varmints. The Vierling had four barrels – a double shotgun with two rifle barrels, in different calibers, underneath. One rifle might be a 9.3mm, the other a 22 Hornet or 22 High Power. One shotgun barrel could be loaded with buckshot (for roe deer) or birdshot (capercaillie).

The triggers to manage all these barrels were something to behold, as was realignment of strikers or hammers, and any kind of safety mechanism. Then there were the sights: On some mechanisms, when I switched over to one of the rifle barrels, the appropriate sight would pop up from the tang.

The others ranged in price from $2,500 to $7,000. There wasn’t quite something for everyone, but close.

With drillings and other combination guns, the most common choice for shotgun barrels is 16 gauge, always a European favorite, followed by 12.

Rifle barrels present much more variety, and even allowed individual gunmakers to chamber for their own proprietary designs.

The market for such guns is mixed. As with virtually every type of gun, there is a collector community; for these men, shooting their guns is not a priority and perhaps never done at all. Others, such as myself, are interested in getting the guns shooting again, especially if they are made for obscure cartridges.

I would much rather acquire a combination gun in 16 gauge and some unidentified 8mm, for which I might have to make my own brass and cast my own bullets, than one with a 9.3x74R barrel, for which ammunition is easily found. First, all things being equal, it will cost less, and second, it will be a lot more fun.

My Peterlongo’s rifle barrel was an immediate puzzle. While it was identified as a 9.3mm – and presumed to be a 9.3x72R – the bore did not slug 9.3, which translates to .366 inches. Instead, it slugged at .350 bore and .358 groove diameter, which is more like a 9mm (.354 inch).

Unlike its big brother, the 9.3x74R, there are many variations on 9.3x72R, with differences reported in both case dimensions and bullet diameter. This appears to be a Peterlongo variation, using a .358-diameter bullet, which really makes it a 9x72.

Johann Peterlongo was noted for introducing several proprietary cartridges, which itself is unusual because he is variously described as a gunmaker, a gun retailer, or a combination of the two. It is known that he was in business in Innsbruck through the latter half of the nineteenth century, that he retired sometime around 1890, his business was taken over (and later renamed) by Richard Mahrholdt, a gunmaker, firearms expert and technical author. Mahrholdt first renamed the business after himself, then later it became Tiroler Waffenfabrik.

It was very common throughout Germany and Austria for gun retailers to have their names engraved on guns they bought in from gunmakers in such centers as Suhl (Germany) and Ferlach (Austria.) For example, I have a gun with Jos. Heinige in Wien engraved on the top of the barrel, but it was actually made by Ferdinand Früwirth.

The Peterlongo has the more conventional “J. Peterlongo Innsbruck” engraved, which usually denotes the actual maker. Various sources insist that the gun is a standard design almost certainly made in Ferlach, and one online website even shows photos of a gun that could be its twin brother, except that it is very plain, devoid of wood carving or much engraving.

The authoritative source I have is Alte Scheibenwaffen, which mentions Peterlongo in one spot as a retailer, in another as a “respected maker,” yet, does not list the company in its rather exhaustive directory of gunmakers. My conclusion from all this is that Johann Peterlongo probably was both a gunmaker and a retailer, selling some guns of his own making, others that he brought in from Ferlach or Vienna – or anywhere else, for that matter. So did Holland & Holland, James Woodward, Boss & Co., and you name it. It was a common practice.

Cartridges of the World mentions several rounds bearing the name Peterlongo, but none that resembles a 9.3x72R necked down to 9mm – but that proves nothing. In the case of a British gun, the proofmarks would tell you pretty much what you need to know, but things are not that simple in Austria. The proof laws and practices there vary depending on in which city a gun was made, with Ferlach, Vienna, and others having distinguishing marks. Proof laws did not take effect in the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the early 1890s; these applied until 1918, with the dissolution of the Empire, at which point Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia went their own ways. Later revisions occurred in the 1920s.

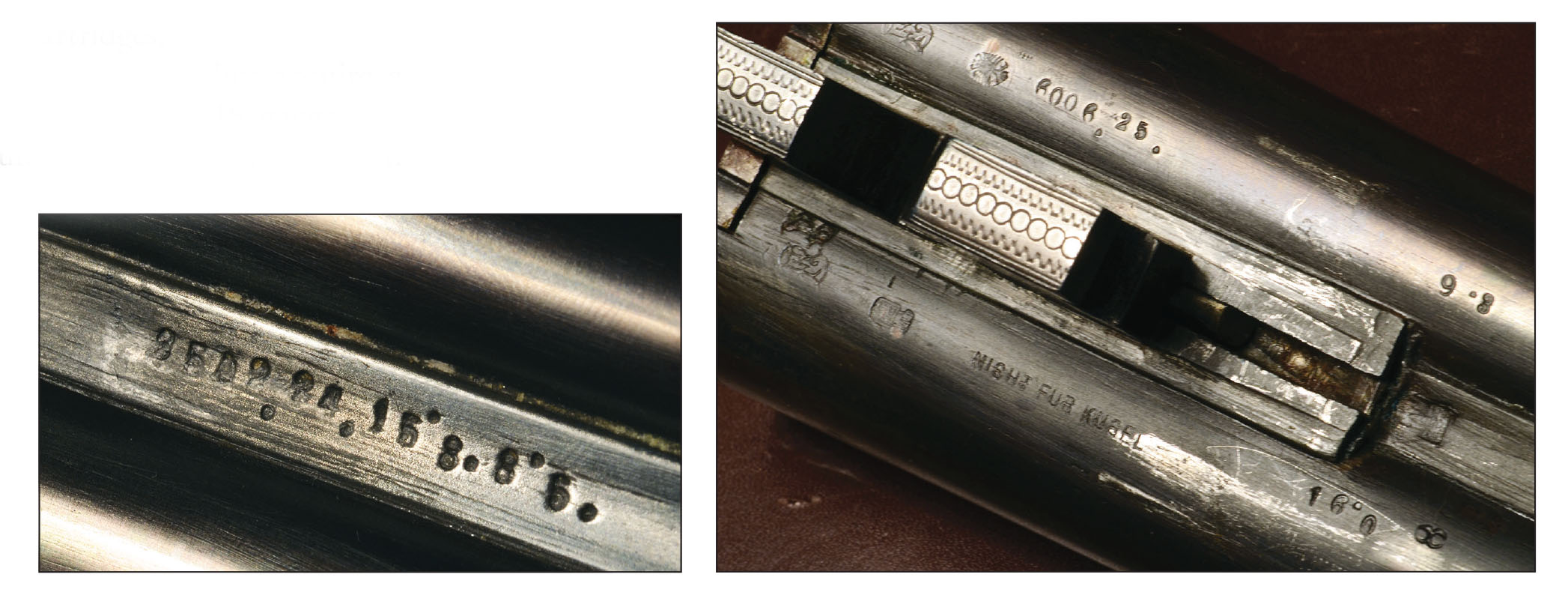

Taking all of this into account, what do the proofmarks on the Peterlongo indicate? Since there were different standards and marks for shotguns and rifles, not surprisingly the 16-gauge barrel has one set, the 9.3mm barrel another. Both appear to have the original Ferlach marks from the first proof law, although none are very clearly stamped. There is also a grab bag of numbers that presumably mean something to an expert versed in Austrian gunmaking, but I am not one, much as I admire them.

There is no indication whatsoever that either barrel was intended for, or proofed for, smokeless powder. The shotgun barrel does have the words Nicht Für Kugel, which is the same as the British “Not for Ball,” indicating a choked barrel. In England, at least, this designation was dropped during the transition to smokeless powder and nitro-proof.

Altogether, between the question of bore diameter and the mysteries of the proofmarks, it’s a rifle that is not going to be fired until I get an expert opinion.

Meanwhile, there it sits, as handsome and graceful a gun as you are likely to see from the long-ago workshops of the craftsmen of Central Europe, and built to a quality that today would cost tens of thousands. A trip back into history is always fun, regardless of the outcome.