Walnut Hill

Hawkeye Borescope

column By: Terry Wieland | May, 17

Sometime around 2002, wandering the SHOT Show, I came upon a booth operated by Gradient Lens Corporation. Laid out on the counter were a number of long, thin, polished steel tubes, with some attachments that looked sort of like eyepieces. It was sufficiently intriguing that I stopped and talked with the representative, a gentleman named Ken Harrington.

Ken had the kind of enthusiasm for the product that comes only from either derangement (We’ve all met those.) or a real belief that this product, right here, this one, is “the answer.” In Ken’s case, it was the latter.

Half an hour later, he had agreed to send me one of these gadgets to try out. Six months after that, having received it, used it and found new uses for it almost daily, I didn’t see how I could live without it. Accordingly, when the time came to send it back, I sent a check instead. It was close to $500, for which I could have bought two or three chronographs, but it was worth it.

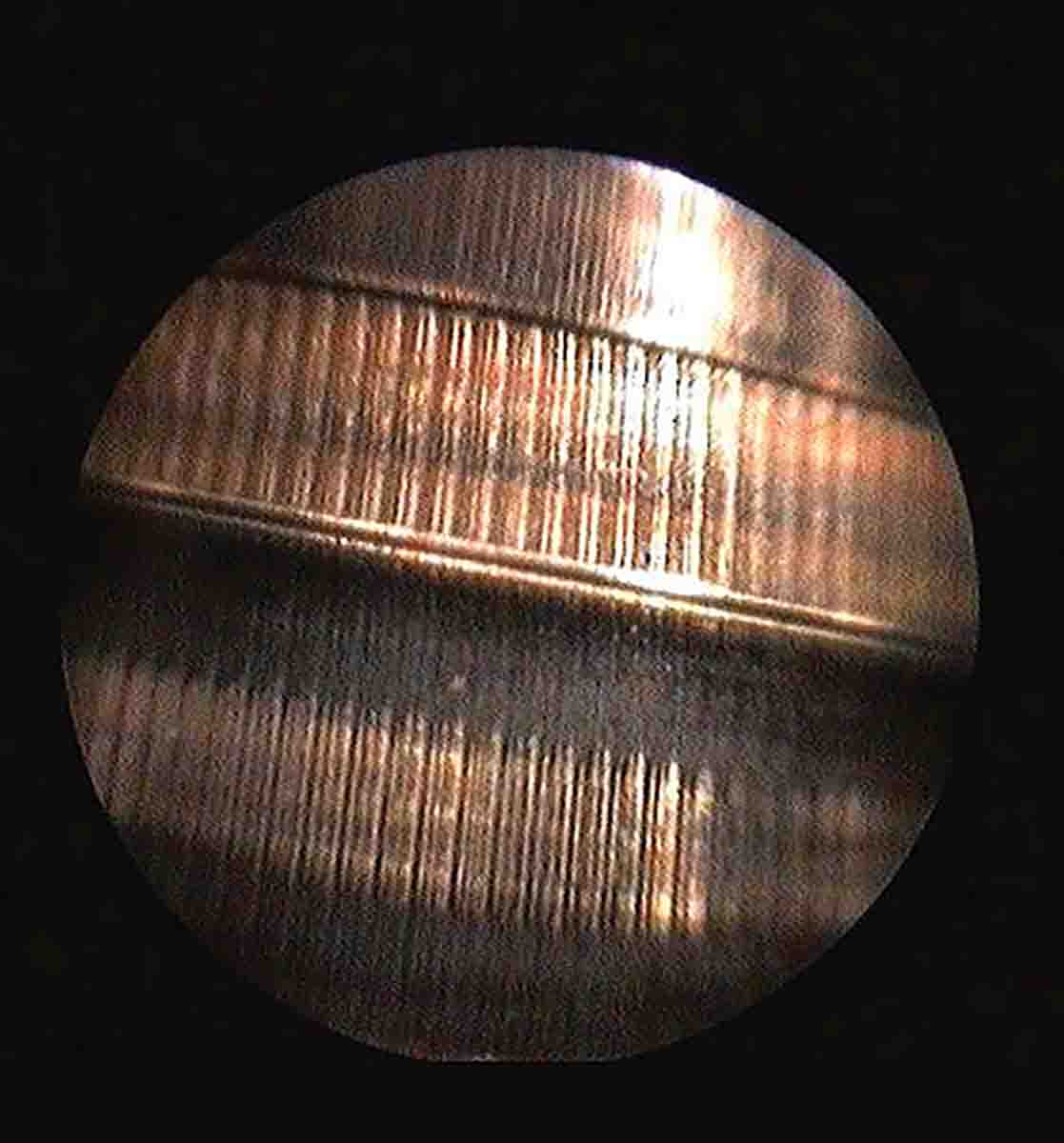

The object in question is called the Hawkeye Borescope. Essentially, it is a miniaturized microscope with a long tube that is fitted with tiny mirrors and a lighting system. It allows you to run it down a rifle bore and examine closely – and I mean closely – the state of the rifling, grooves, lands, chamber throat or anything else within 18 inches of either the bore or the breech.

Obviously, the borescope is not a new product, since Gradient has been around since 1995. What is new is the company’s special Shooting Edition that came out last year. It’s a bare-bones version, more simply packaged and retailing for considerably less now than I paid almost 15 years ago. What’s more, it uses different materials in vulnerable spots to resist such things as the aggressive bore solvents and other goop we stuff down our barrels. I never ran into any such problems with my old Hawkeye, but then I tend to be pretty careful about such things.

In the years since I first encountered Gradient at SHOT, a lot has happened technologically, especially in the fields of computers, digital instruments, digital imaging and video. Gradient has expanded its line in every direction, adding new versions and vastly expanding the capabilities of the borescope. The Gradient catalog is now 35 pages, and half of what’s in there completely baffles me. If you are a techno-geek with unlimited funds and an insatiable curiosity, however, you could go wild buying accessories, accoutrements and add-ons, connecting micro-macro video equipment to your borescope, and then connecting the video to your computer, and then the computer to the jumbotron down at the stadium.

This is why it was somewhat puzzling – but definitely gratifying– that Gradient thought to go the other way and make a version of the Hawkeye Borescope that is simpler, easy to use and, most important, affordable for the average shooter.

Without a doubt, the most important technological advance for shooters in the last 25 years has been the almost universal use of chronographs, made possible because they are now smaller, simpler, and much, much cheaper. Anyone who can afford to handload can afford a reliable chronograph. For the first time in history, shooters can discuss the relative merits of cartridges and loads using accurate, proven velocity figures, instead of extrapolation, guesswork and wishful thinking.

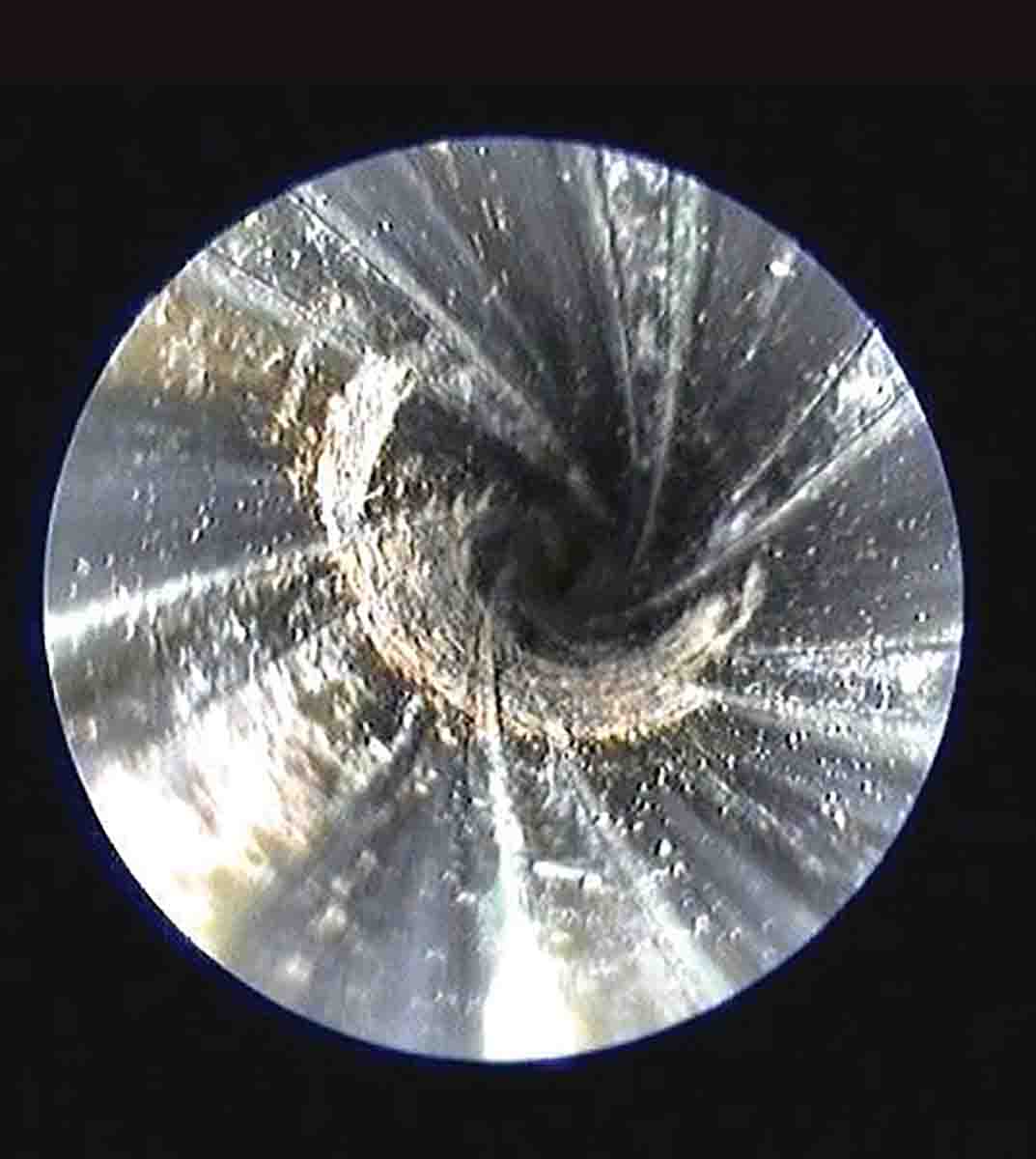

A lesser problem, but one that bedeviled riflemen for centuries, was knowing exactly what happens at the breech end of the bore, in the chamber, throat and leade. More accuracy problems have been blamed on throats that have been washed out by scalding gases than anything else I can think of. A borescope allows examination of the throat for actual deterioration.

The obvious use is the one I initially put my borescope to, which is checking the lands and grooves for stubborn patches of cuprous fouling. If a patch keeps coming out blue regardless of how many treatments have been applied, chances are there’s one isolated deposit somewhere in there. Find it, and then concentrate cleaning efforts on that exact spot and get rid of it pretty quickly.

Muzzleloaders and black-powder guns generally – especially really old ones – often have bores that look like the tunnel into a toxic waste dump, but because the bore can’t be seen, it is impossible to identify what problems you are really up against, much less exactly where they are and how to deal with them. The borescope helps here, although it can be limited by length. Still, it’s better than nothing, and if you are really zealous, there are accoutrements available from Gradient that will turn a borescope into a meandering video camera that can send images back to a computer

Lock time, and consistency of striker travel, can make a real difference in how well a rifle shoots. For years I wrestled with that, with one military rifle after another, shining flashlights into the bolt and performing all sorts of contortions to see what I was dealing with. It’s also good to know if attempted cleaning or alterations have actually accomplished anything beyond heartache. The Hawkeye Borescope, bless its little stainless steel heart, has made these concerns a thing of the past.

It is also supremely useful for examining the interior of tubular magazines for rust, debris, dents and all the other little annoyances that reduce their performance. If I was a serious Winchester or Marlin collector, I’d get a Hawkeye just for that purpose.

Using the Hawkeye without the mirror that allows right-angle views of bores and rifling adds another dimension to its usefulness. Again, lever actions are among the worst for having hidden areas inside the receiver with a lot of moving parts that are almost impossible to see without dismantling the whole thing. Like the inside of a bolt, smoothing, polishing or lubricating the inside of these frames, and the moving parts therein, can turn a rough lever action into one that is smooth as glass.

I long ago lost count of all the hours I’ve spent trying to correct what I thought was a problem, only to throw up my hands, take the offending piece to a gunsmith and find out that the difficulty lay in a different area altogether.

Looking over what I’ve written here, which really only scratches the surface, I realize I now sound the way Ken Harrington did, talking to me 15 years ago at SHOT. And no, it is not derangement. At least, I don’t think it is.