Hodgdon’s “60 percent rule” for H-4895 cured headspace problems in an old Rolling Block.

Among our reasons for handload ing, one in particular requires more knowledge and perhaps a bit of intuition that comes only with considerable experience and that is getting old rifles to safely shoot their obsolete cartridges. While it’s fairly simple to work up loads for modern cartridges in modern firearms, very often, handloaders must troubleshoot and solve a number of convoluted problems before we can even begin load development for centenarians.

That’s all it takes. Even though the action closes, the slight protrusion of the rim on an overexpanded case prevents the hammer from falling.

When military surplus (milsurp) Model 1897 and Model 1902 Spanish No. 1 Remington Rolling Block rifles hit U.S. markets in the mid-twentieth century, the correct German-manufactured milsurp 7x57mm (aka 7x57 Mauser, 7mm Mauser and 7mm Spanish) ammunition accompanied them. However, when buyers of the old rifles fired commercial factory 7x57mm cartridges in the Rolling Block, many suffered noticeable case stretching and occasional case head separations.

This reputation may have helped keep the prices of these antique Spaniards reasonable, prompting me to purchase one at a live auction. Upon first firing, I found the rifle did, indeed, stretch brass cases. The problem in the Spanish 7x57mm Rolling Block is, as you probably guessed, a matter of headspace. Developed by Peter Paul Mauser in 1892, the cartridge is the stablemate of the limited-run Mauser Model 1892, though it is more recognized in its pairing with the Spanish Mauser Model 1893 rifle of Spanish-American War fame. So, in addition to being a foreigner, the 7x57mm cartridge predates the cartridge dimension and pressure standards set by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI), which didn’t set up shop until 1926. Commercial cartridge pressure alone isn’t an issue, as SAAMI pressure for the 7x57mm cartridge is only 46,000 CUP, (copper units of pressure) whereas the original loading for the Spanish version was 50,370 CUP. But it is a factor for another reason we’ll see in a moment.

The factory load primer showed some flattening (right), a sign of excessive headspace. A reduced load fired primer (left) appears normal.

According to a Remington representative responding to an

American Rifleman NRA Technical Staff query back in 1956, as originally manufactured, Remington’s turn of the century Spanish military Rolling Blocks have chambers .0065 to .0131 inch longer than today’s SAAMI standard 7x57mm chamber length, and of course, German 7x57mm cartridges of the day were manufactured to fit. This is the reason there was no problem shooting period milsurp ammunition in the Spaniards, and yet, for modern cases stretching to the point of separating case heads.

I fired five Prvi Partizan 139-grain 7x57mm factory cartridges in the Rolling Block to see if the Spaniard’s case-stretching reputation followed this particular rifle. Velocity averaged 2,674 feet per second (fps) and cases stretched .013 inch, reproducing the additional chamber length quoted by that Remington rep back in 1956. Primers showed moderate but definite flattening, a sign of excessive headspace.

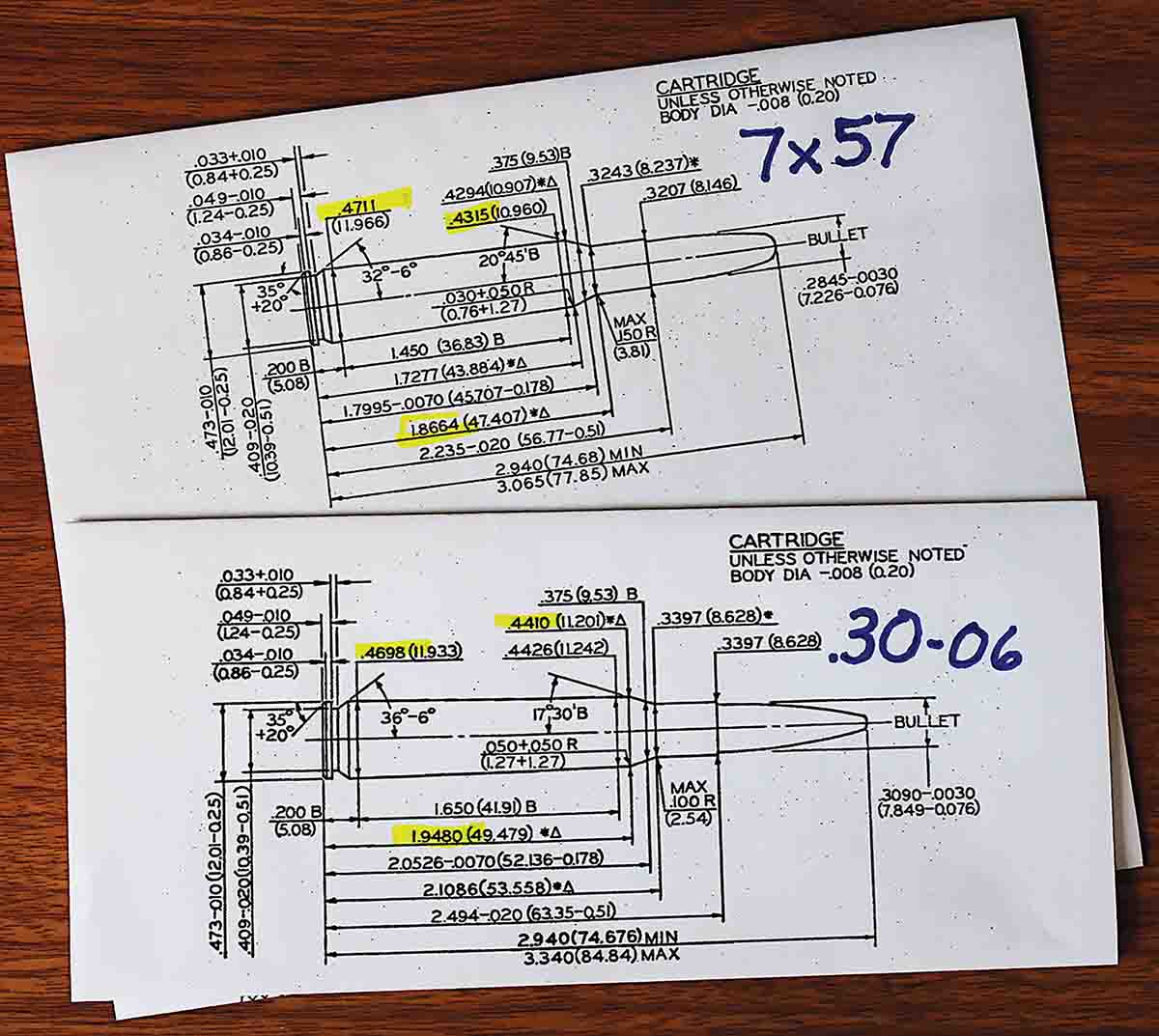

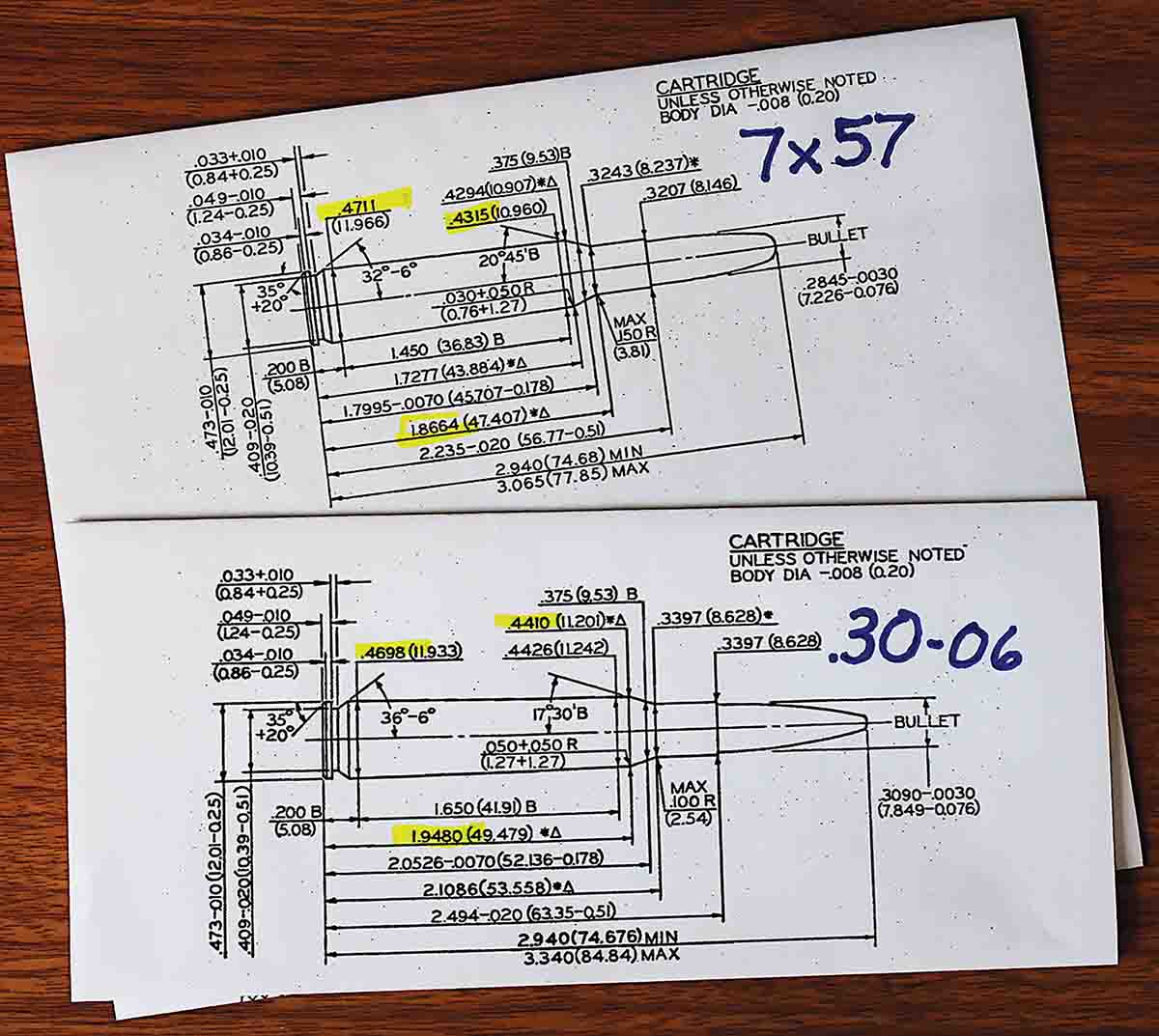

SAAMI cartridge dimensional drawings show the 30-06 resizing die can be used to resize the 7x57mm case base without touching the shoulders.

Fired cases revealed a second complication: the Spaniard’s military chamber is oversize. Outside neck diameter of fired cases expanded .018 inch, and shoulders expanded about .006 inch, as did the case near the base. The photo of the factory case with the fired case showed the shoulder angle has changed considerably, and both the shoulder and the case body have visibly expanded. Armies care nothing for the reloader; many military rifle chambers were made deliberately slightly oversized to facilitate loading dirty ammunition into dirty rifles under dirty field conditions.

Neck sizing the cases fired in this rifle’s oversize chamber did not, of course, resize the case body, with the result that neck-resized cases would not chamber fully. The extractor gouged some (empty) neck-resized cases at the base when forcing the case home, and the breechblock refused to roll the last few thousandths fully into battery, which did its proper job in thus preventing the hammer from falling. All this was not unexpected without full-length resizing cases fired in a military chamber. Subsequent full-length resizing these cases alleviated all these problems but reintroduced the original one: excessive headspace, as the sizing die pushed shoulders too far back.

This .75-inch group shows the old rifle is still capable of good accuracy with low-pressure loads.

Running neck-resized cases into a 30-06 die with the decapping rod removed, resized the 7x57mm case at the base without touching the shoulders (and thus reintroducing the headspace problem) allowing cases to chamber again, but this solution is not entirely satisfactory. Just as repeatedly bending a paper clip can cause it to break from metal fatigue, repeatedly overexpanding and resizing the case back down again would likely still lead to an eventual case head separation.

A better and simpler solution, of course, is to load cartridges to a low enough pressure that the cases would not require full-length resizing. But as it turned out, even minimum published 7x57mm rifle powder loads overexpanded cases. Cast bullet shooters routinely resort to pistol powders in rifle cases to keep pressure and velocity down, but only a minority of handloaders cast bullets. Is it possible to get the desired results from jacketed bullets and rifle powder?

Full-power factory load cases fired in the Rolling Block no longer fit into a Lyman Ammo Checker cartridge headspace gauge. The gauge is made to minimum SAAMI chamber specifications.

Reduced loads can extend brass life and stave off those eventual case head separations. The concern with reducing powder charges, however, is that reducing too far can cause other problems, including velocity excursions, poor accuracy and bullets getting stuck in bores. The most serious is a phenomenon called detonation, in which the cartridge and the firearm suffer catastrophic failure – a “kaboom.” Detonation is associated with a comparatively large cartridge case containing comparatively little powder. Theories for the cause include a simultaneous ignition of all powder granules producing instant pressure, or shock waves propagating inside the too-empty case. The phenomenon isn’t definitively understood, beyond that “kabooms” have happened and can happen again.

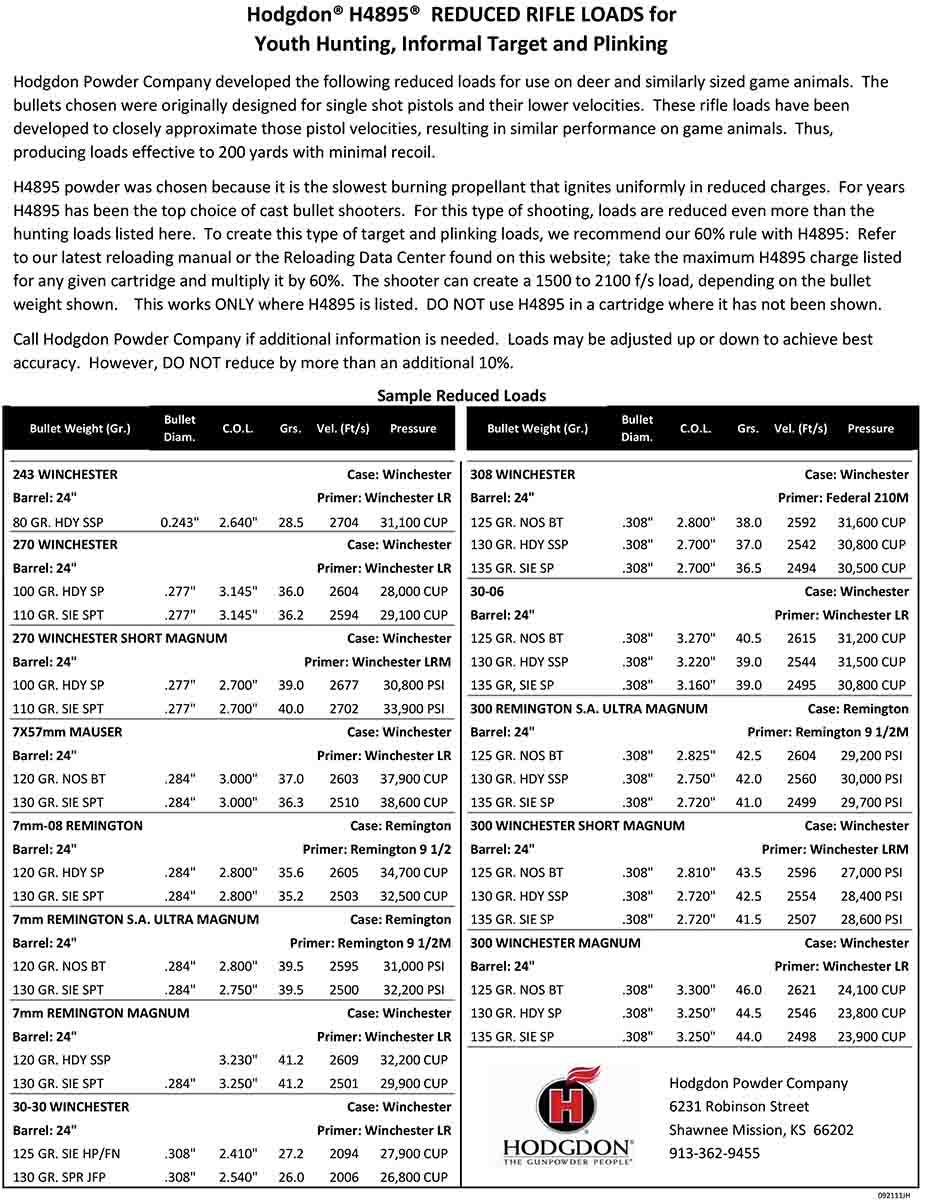

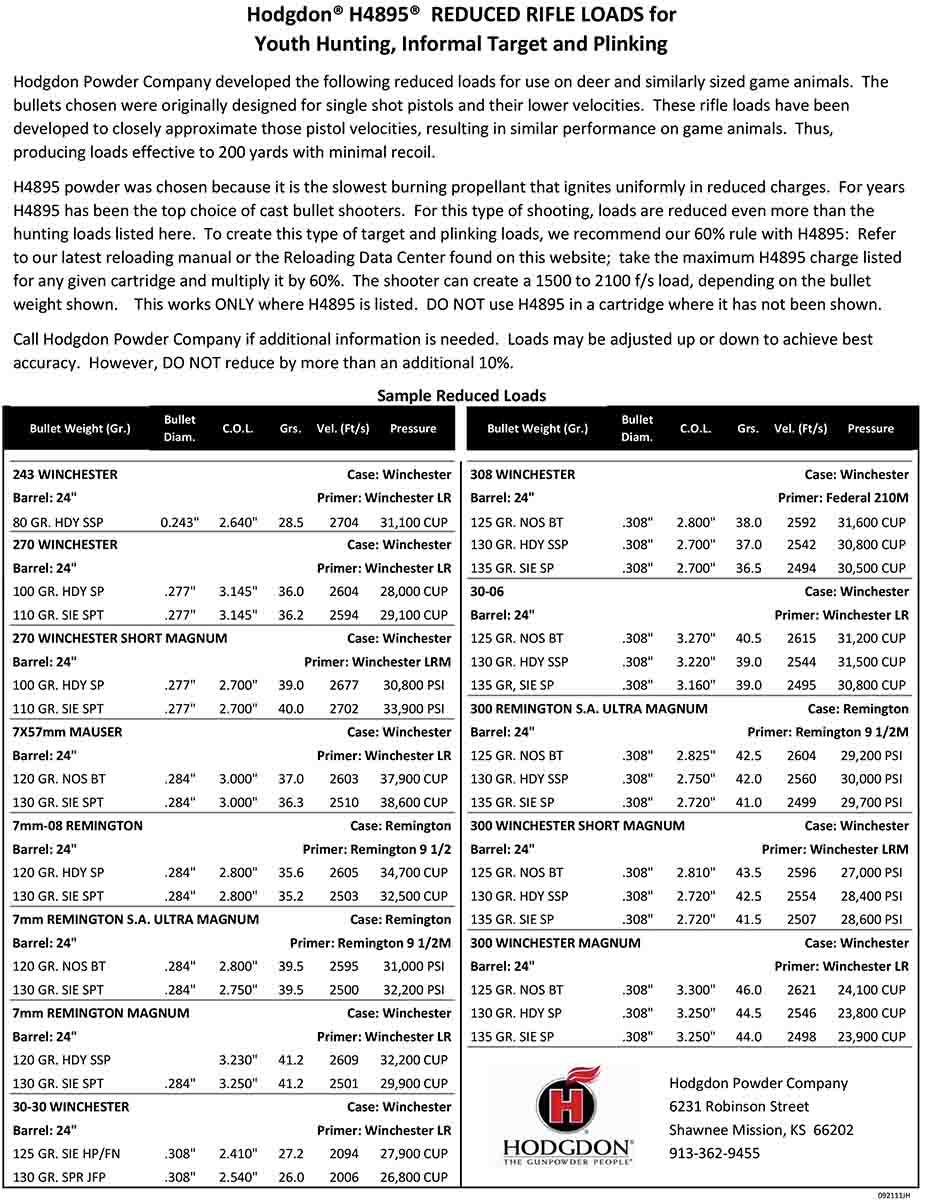

Hodgdon helps out by having developed specific reduced loads for a variety of rifle cartridges, including the 7x57mm, utilizing H-4895. These charges produce pressures below 40,000 CUP. In this military Rolling Block, however, even the minimum listed charge with lighter 120-grain bullets caused too much case expansion.

After neck sizing a reduced-load fired case, protrusion from the gauge is .013 inch.

Ah, but Hodgdon also has a “60 percent rule” that can be applied to Hodgdon’s own standard H-4895 load data (not Hodgdon’s separate reduced load data; type “Hodgdon 60 percent rule” into your browser bar to find the downloadable PDF). The rule is to note the maximum H-4895 charge listed for any given cartridge and bullet combination in the Hodgdon load data and multiply it by .6 (60 percent). Hodgdon stated that this should produce velocities of about 1,500 to 2,100 fps for the bullet weight listed, and Hodgdon cautions against reducing these charges by more than another 10 percent. It bears emphasis here that Hodgdon specifically selected only H-4895 for this 60 percent rule because it is the slowest rifle powder to ignite uniformly in reduced loads. Do not substitute any other powder, including IMR-4895, when using this 60 percent rule.

This case was fired with a 60 percent load and neck resized. Shooting it and dropping it in the Lyman Ammo Checker showed the over-expanded case walls caused by the oversize chamber prevent the case from fully entering the gauge (the shoulder hasn’t touched the gauge), yet it still chambers in the military rifle.

I pulled the bullets and primers and dumped the powder from the Prvi Partizan ammunition to make my own loads. Sure enough, applying the 60 percent rule to make a minimum test charge of 25.2 grains of H-4895 reduced 120-grain bullet velocity to 2,191 fps; reducing that another 10 percent to a rock-bottom low of 22.7 grains slowed bullets to 1,945 fps. Working up from that point gave the Hornady 120-grain Varmint bullet the best accuracy at 1,992 fps with 23.5 grains of powder. Sierra’s 130-grain hollowpoint and Prvi Partizan’s 139-grain softpoint each turned in an exceptional group, demonstrating the old Spaniard is certainly capable of excellent accuracy. The overall large group sizes we can attribute to a combination of tiny sights and older eyes. More to the point of this exercise, with the lighter charges in the accompanying table, cases did not overexpand and they readily rechambered after only neck resizing. With the heavier charges listed in the table, overexpansion began to cause some cases to not seat fully in the chamber, again causing the rifle to not fire.

Neck, shoulder and case body all show obvious expansion (right) compared to an unfired factory round (left).

Note that the cartridge overall length (C.O.L.) for the heavier bullets in the accompanying table is long, exceeding the SAAMI standard of 3.065 inches. Original Spanish 7x57mm cartridges featured roundnose bullets, placing the ogive well forward. The spitzer bullets used here have ogives set further back, necessitating seating them out for a longer C.O.L. to get ogives closer to the rifling for less of a “jump” before engaging the rifling, an aid to accuracy.

This old Spanish Rolling Block is not destined for combat or even hunting, it is a historical curiosity for occasional shooting, and so a lower bullet velocity is of no consequence. Of course, a permanent fix is to have a gunsmith set the barrel back and rechamber it to the shorter SAAMI standard, but this would negatively impact the rifle’s intrinsic value as a historical artifact. Rechambering old guns is a solution for shooters, but the challenge for handloaders is not in making an old gun fit a newer cartridge, but in replicating old cartridges to fit old guns.

.jpg)