Bullard Repeating Rifle

America's Better Lever Action

feature By: Art Merrill | May, 24

Bullard lever-action repeating and single-shot rifles had and have a reputation for high quality, but the 1881 newcomer Bullard Repeating Arms Company was apparently too small to compete successfully in the commercial world against already established monsters like Marlin, Remington and Winchester. Or perhaps, it just wasn’t managed well enough to do so. It didn’t help that Bullard rifles cost nearly twice that of its competitors so, unlike the Marlins and Winchesters, Bullard’s were pretty much out of the financial reach of “Everyman,” America’s most lucrative civilian market.

Bullard’s company might have lasted longer or survived if it had focused on chambering its rifles in already extant calibers, but Bullard instead manufactured rifles for its own proprietary cartridges, though standard calibers could be ordered from the company. Teddy Roosevelt owned a six-shot Bullard rifle in 50-115 Bullard, but factory cartridges loaded by Remington and Winchester were already getting scarce on store shelves when he died in 1919. They have been extinct for nearly a hundred years.

Bullard repeaters came in large and small frame variants, depending upon caliber, with calibers 40 and above chambered in the large frame rifles. The one presented here is a small frame repeating rifle chambered in 38-45 Bullard; the 32-40 Bullard also utilized the small frame. The action is, indeed, exceptionally slick and completely lacking in any loose play, rattle or lever droop we find present in other leverguns. Closing the lever completely depresses the lever safety catch without the need to maintain squeezing pressure on the lever to do so, as found on other lever-action rifles.

Bullard’s differ significantly from those others in having a rolling or swinging block, like that found on single-shot rifles such as the Remington Rolling Block rifle, interposed between the hammer and the bolt (Bullard referred to it as a “vertically swinging breech-block”). Upon opening the lever, the block tips backward and down; it rises and rolls forward upon closing the lever and is supported by a vertical brace that tips forward into position underneath the tail of the breech block. The combination of the brace, block and breech bolt makes for an exceptionally strong lockup. One can feel the lever “camming over” at the very end of its closing stroke as the action locks up tight. The hammer strikes a pin in the breech block that in turn transfers the energy to the firing pin in the breech bolt.

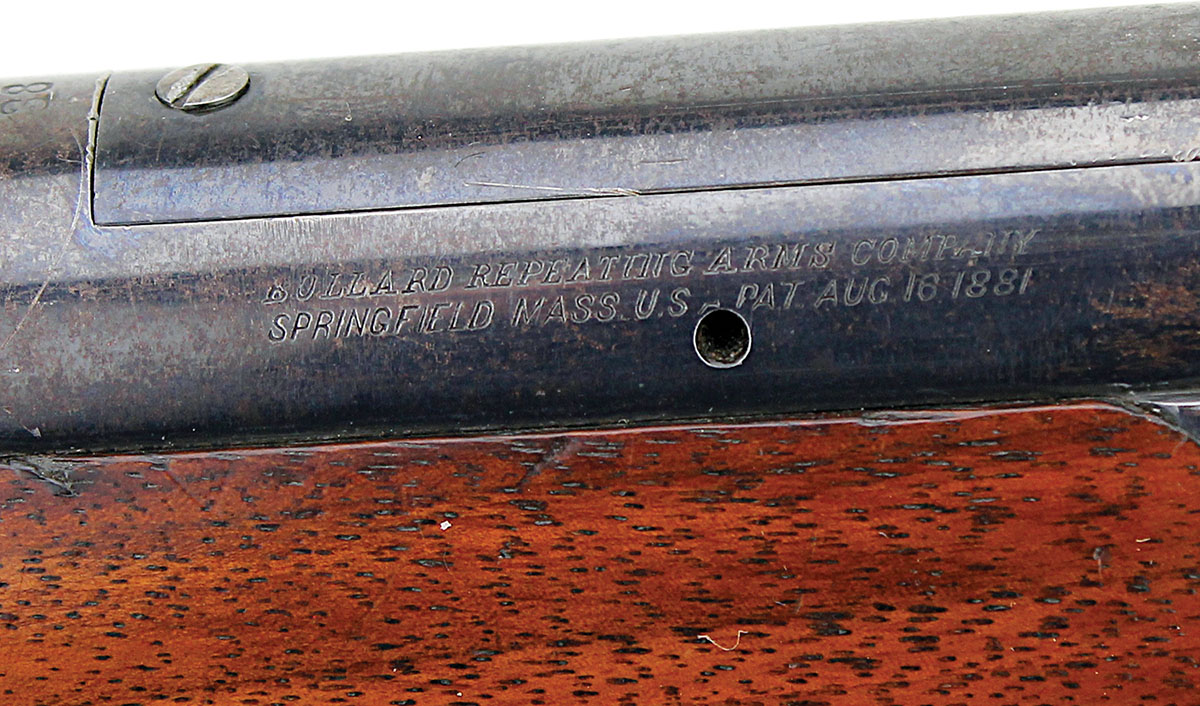

Two removable side plates on the receiver mimic those on Winchester’s Model 1873, as does a sliding dust cover on the receiver top. Three screws in the upper tang protect threaded holes that allow acceptance of a variety of tang sights. Very tiny serif script stamped into the left side of the receiver identifies the rifle with:

BULLARD REPEATING ARMS COMPANY

SPRINGFIELD MASS U.S. PAT AUG 16 1881

Another James Bullard innovation, a small hole appears in the left wall of the receiver below the factory stamps. In the event of the long, thin extractor breaking in the field, the hole permits accessing the extractor retaining pin to drive it out and back in without the need to disassemble the receiver to replace it.

There’s still plenty of original factory bluing on this Bullard; freckles of rust on the barrel and magazine tube have been treated and cold-blued. Brighter bluing on the rear sight hints that it might be a replacement. The hammer, trigger, lever and forend tip appear to have been color-case hardened; if so, all trace of color is gone now.

The forearm and buttstock wood show some figure and still wear a deep oil finish that comes with hand-rubbing. Certainly walnut, the wood has a light to medium stain with a hint of red visible under the right light. The wood-to-metal fit is excellent, as to be expected on a high-end rifle, with not a single split or crack in the wood where it meets steel.

With Bullard guns came Bullard proprietary cartridges, all of black-powder design and all made immediately obsolescent with the concurrent introduction of smokeless powder in 1885. All were unremarkable in that they brought no new performance or compelling advancement over existing cartridges, with the exception of the 50-115 Bullard. This latter cartridge was America’s (and probably the world’s) first semi-rimmed design and first cartridge case incorporating a solid head, small factoids lost to history.

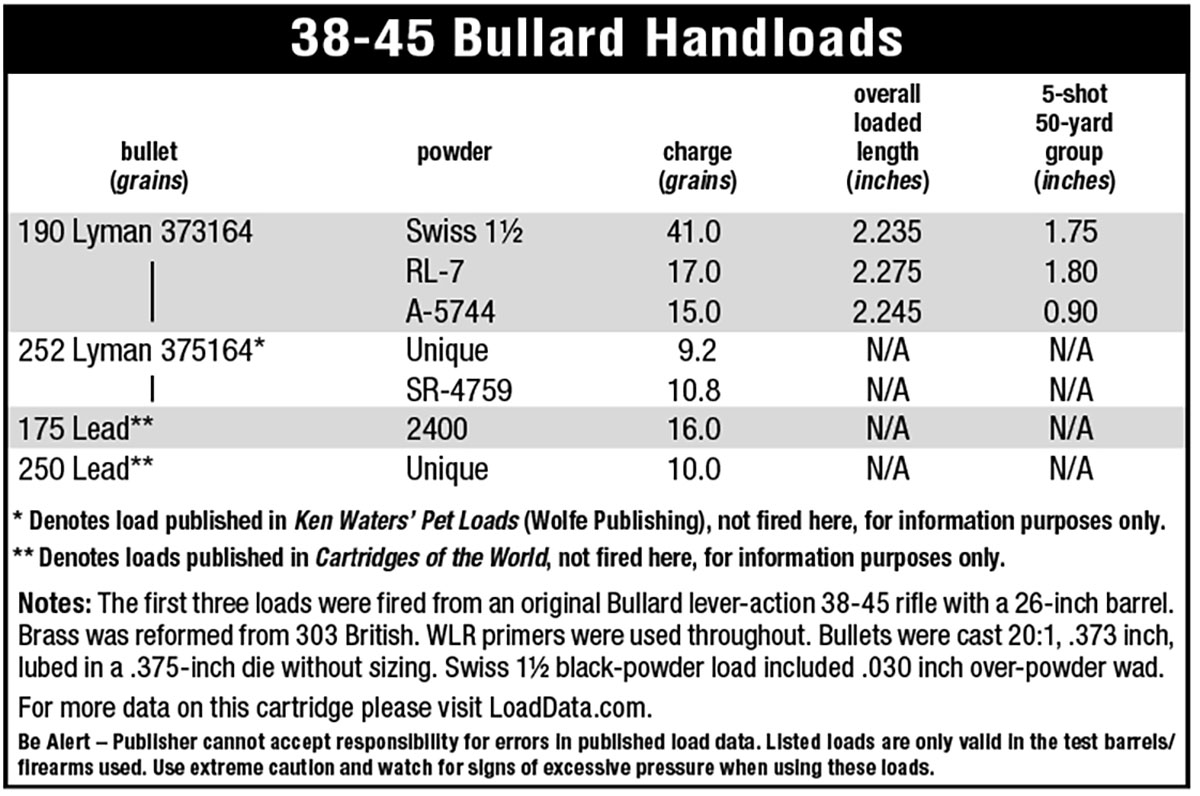

Ballistically similar to Winchester’s 38-40 WCF, the 38-45 Bullard cartridge enjoys a slight velocity and muzzle energy advantage over the original Winchester round, eclipsing it generally with a little over 200 feet per second and not quite 300 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. The Bullard’s 38-45 twist rate is variously given as 1:16, 1:18 and 1:22; a change in twist rate during production could account for the disparate reports. Made to take an original .373-inch bullet, the bore on this particular rifle slugs closer to .368 inch. As previously noted, factory ammunition has been out of production for many decades and Bullard cartridges are collector items today. Handloading the 38-45 Bullard is doable but not for the beginner or the impatient. For the moment, let it suffice to say that brass had to be converted from 303 British and 30-40 Krag, and bullets cast from an old Lyman No. 373164 mould; a few loads appear in the accompanying table here for informational purposes.

A Lyman tang sight accompanied this rifle, but required removing the barrel-mounted rear sight in order to see the front sight. I found that a Marbles Improved

In the end, Bullard Repeating Arms Company manufactured no more than 2,200 of its large-frame and small frame repeating rifles between 1883 and 1891, according to the exhaustive work on the subject, Bullard Firearms (G. Scott Jamieson, Schiffer Military History, 2002). That number is divided between 1,700 large-frame rifles and 500 small-frame rifles. All told, Bullard made approximately 2,800 repeating and single-shot rifles. Serial numbers of Bullard rifles run higher, but Bullard assigned the various model rifles serial number blocks, so the serial numbers do not start at number 1 and run sequentially without a break. Jamieson writes that single-shot Bullards, for example, were assigned serial number block 3501 to 4100, indicating manufacture of no more than 600 of the single shots – and possibly less, as the highest serial numbered Bullard rifle known to Jamieson is number 4076. Apparently, after creating his rifles, James Bullard turned company management over to someone else in 1885 so that he could pursue other inventions (including a working steam-powered automobile marketed as the Victor Steam Carriage by the Overman Automobile Company at the turn of the century), and Bullard Repeating Arms Company folded by 1891.

Surviving Bullard lever-action rifles, both repeaters and single shots, are obviously quite rare today. Because Bullard cartridges disappeared rather quickly and as a result, these rifles have generally been fired little; because the rifles are so well-made; and because such comparatively expensive guns tend to be pampered by those who have pride of ownership,

Despite the complexity of handloading for Bullards, few owners seem willing to part with these rifles that they generally cannot shoot, instead, keeping them as investments or as historical curiosities. That’s a pretty good endorsement for an American rifle that eclipsed the mainstream in quality and ingenuity and failed only in the business aspect.