The 270 Winchester: Young at 100

It’s Flat Arc and Lightning Kills Charmed Hunters

feature By: Wayne van Zwoll | March, 24

Initially offered only in 270 Winchester and 30-06, the 54 would add eight more chamberings. They were, in order of increasing rarity, the 22 Hornet, 30 W.C.F. (30-30), 250 Savage, 7x57 Mauser, 257 Roberts, 220 Swift, 7.65x53 Mauser and 9x57 Mauser. Sporter versions of the 54 were most common; nine others included Target and Sniper models with Marksman-style stocks, leather slings and scope blocks.

Winchester’s Model 54 was cataloged and available through 1941, though production slowed to a trickle in the last five years. Of 52,029 Model 54s shipped, 49,009 were boxed by the end of 1936. It was hardly a perfect rifle. Its trigger also served as a bolt stop, disappointing competitive shooters. The speed lock was blamed for occasional misfires. Weaver’s 330 scope was blocked by the top-side safety.

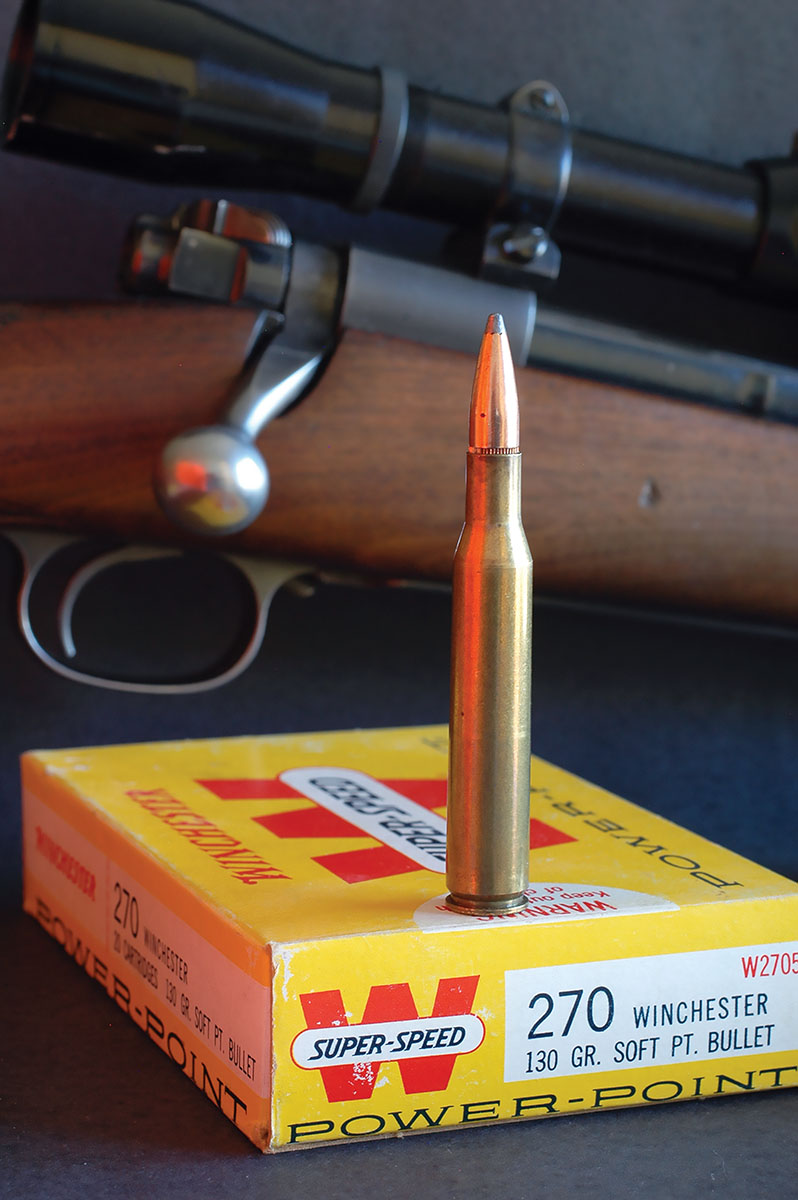

O’Connor has long been hailed for breathing life into the 270. His first rifle so chambered was a Winchester 54, acquired in its debut year. Decades later, he wrote of hunting deer with his new 270. Over open sights from the sit, he swung with a buck “trotting along a hillside” 200 yards off. Thunk! His bullet hit the paunch. Chiding himself for the lousy shot, he trailed the animal and finished it. He was astonished at the damage done by the little 130-grain softnose. Shortly after, he installed a Lyman 48 aperture sight on that Model 54 and had it restocked by R.D. Tait of Dunsmuir, California.

Some years later, Phoenix barrel-maker Bill Sukalle sold O’Connor a flat-bolt Mauser fitted with a 24-inch 270 barrel for $35. Ace Wisconsin stocker, Alvin Linden added “plain, straight-grained but very hard and stable Bosnian walnut, superbly shaped and checkered” for $75. Frank Pachmayr installed a 2½x Noske scope in a Noske mount on a Pachmayr base. This rifle, wrote Jack, “made a real .270 fan of me.”

Why a .277-inch diameter bullet? Surely that puzzle fueled many campfire debates in 1925. No other cartridges fired a bullet of that size. A 7mm (.284-inch diameter) missile would have seemed a more logical choice. The 7x57mm Mauser, in 1892 early to the smokeless party, had a following among both hunters and military units worldwide. In England, it became the 275 Rigby. The 7x64 Brenneke, circa 1917, had more spunk. The flanged and belted 275 H&H Magnums used .284-inch bullets too. (Perversely, the other 7mms of the period – the 280 Flanged Nitro Express, 280 Ross and 280 Jeffery – featured .287-inch bullets, as did the 7mm Rigby Magnum that blessed double rifles in 1927.)

Allegiances aside, the 270 excited hunters. Its frothy working pressure of 65,000 psi drove a 130-grain bullet at a listed 3,140 feet per second (fps). It beat Savage’s 87-grain 250-3000 bullet off the blocks, with a decided advantage in bullet weight. At 300 yards, a 270 softpoint was still clocking 2,320 fps – faster than 30-30 bullets left the muzzle. Not all was roses, however. Bullet jackets of the day, developed when 2,600 fps was a blistering exit, were prone to shatter at impact velocities approaching Mach 3. Fragmented cores failed to penetrate. Hunters accustomed to the slow, thick bullets of black-powder times also groused that the explosive upset of 270 bullets pulped their venison, which was a fair point. But when Winchester introduced a meat-saving 150-grain load throttled to 2,675 fps, it didn’t sell.

The barrel and receiver looked like the 54s, but the Model 70s trigger was better and could be adjusted for take-up, weight and overtravel. While not “magnum-length” by strict definition, the action cycled cartridges as long as the 375 H&H. A strong, non-rotating Mauser extractor controlled cartridges from magazine to chamber. The separate bolt stop arrested the left lug. For cartridges shorter than the 30-06 and 270 Winchester, an extractor collar extension limited bolt throw. The firing pin travel was increased by 1⁄16 inch to avoid misfires. A hole in the receiver ring backed up bolt-head gas ports. The Model 70s first safety, a top tab that swung horizontally, dodged most scopes. But it would be replaced in four years with a side-mounted, three-position wing. In place of the Model 54s stamped, fixed bottom metal, the Model 70 boasted a hinged floorplate and trigger guard, both machined. Hunters praised those improvements. Competitive shooters applauded adoption of the Model 54’s Marksman stock.

The 270 Winchester is a hunter’s cartridge. But the Great Depression took Model 54s off the Christmas wish lists of many hunters. I have no other way to explain the results of a 1939 survey conducted by the state of Washington’s Department of Game. Besides data on the 1938 harvest, it tapped the cartridge preferences of elk hunters. Not surprisingly, the 30-30 and 30-06 turned up most often, the 30-40 Krag next. Those rounds (with the 30 Remington, not broken out but almost surely on the hunts) appeared in 1,372 responses – 60 percent of the 2,285 recorded.

What was missing from the top 15 of 44 cartridges named on this roster was the 270 Winchester. Then well into its second decade, no doubt with many elk to its credit, it was named just nine times, same as the 44-40 and the 22 High-Power.

Results of my elk hunter surveys during the 1990s, after the debut of versatile rimless cartridges like the 308 Winchester, 280 Remington, 25-06 and 7mm-08 – and a flood of short, belted magnums – were different. The 30-06 kept its crown, but shared it with 7mm Remington Magnum. The 270 and Winchester’s 300 Magnum followed, ahead of that company’s 338 Magnum and many other fine elk cartridges. The 270 still makes a strong showing where elk and mule deer abound.

Jack O’Connor used the 270 to take at least 38 game species. One year, he reported firing 10,000 rounds, hunting and in range trials. He bought his first Model 70 270 in Tucson, Arizona, in 1943. Alvin Linden stocked it in time for Jack’s first Canadian pack trip that fall.

O’Connor scoped it with a Weaver 330 and used it to collect his first bighorn, mountain goat, caribou and moose. In 1953, Al Biesen turned down and shortened a standard M70 barrel to furnish Jack with a lightweight 270. The Winchester Model 70 action wore a Stith Kollmorgen 4x scope in Tilden rings. That rifle accompanied Jack on hunts to India, Iran and central Africa. In the Yukon, it downed a 40-inch Dall ram.

“I have shot more rams with .270 rifles than with anything else [and don’t] know of a better sheep cartridge,” declared Jack in 1962. But with hosts of other hunters, he found it deadly on tougher game too.

In the fall of 1944, after sneaking across a broad Wyoming canyon, O’Connor leveled his 270 at a big bull elk. One 160-grain Barnes copper bullet was enough. “Since then,” he wrote much later, “I have used the .270 for elk almost exclusively – sometimes with 150-grain bullets, but mostly with 130 grain.” On a hunt with Wyoming outfitter, Les Bowman, his only chance came at long range. O’Connor rested his rifle on his jacket over a stone. “When the .270 cracked, the elk fell …. he did not even kick.”

A moose hunt had yielded no sightings when, to change his luck, O’Connor swapped his 30-06 for his 270. Not long thereafter, a bull popped from the bush. As the animal quartered away, “I put a 130-grain Silvertip behind the last rib on the left side up into his right lung.” The follow-up shot, he insisted, shouldn’t count, as even a well-hit moose “has to think about it for a while before he realizes he is dead.” Jack would take 11 more moose with 270s.

Having handloaded for the 270 since the 1970s, I’ve sent lots of bullets from quite a few rifles. So my dearth of data is embarrassing. My defense: Early on, a friend sold me a 30-pound drum of surplus Hodgdon H-4831 for $1.50 a pound. I found most hunting bullets for the 270 liked H-4831, and every 270 rifle that comes to mind from those days met my standard for good hunting accuracy: 3-inch groups at 200 yards. For many shooters nowadays, that bar is pretty low. But 1½-MOA accuracy will still keep bullets in a 6-inch circle at 400 yards. That’s a long poke at game.

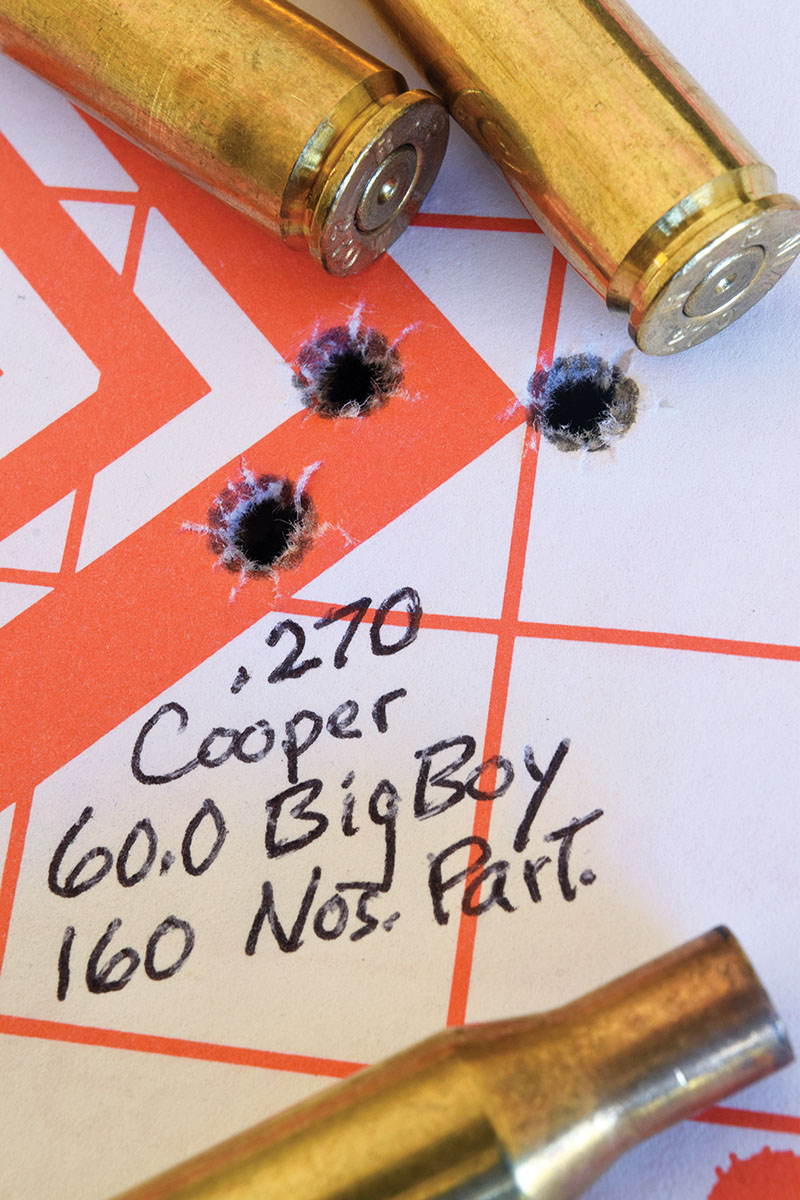

I consult several manuals when trying new loads, then weigh every charge on my Ohaus balance beam, as was my habit 50 years ago. Call the exercise therapeutic. It also yields safe, uniform loads. My go-to recipe for deer during the Nixon administration was 60 grains of H-4831 driving Speer 130 grains. For elk, I loaded 58 grains of H-4831 behind Nosler 150-grain Partitions. I used standard large rifle primers – typically CCIs.

This year, I tapped a few powders and bullets that weren’t available when my loading press shared counter space with my toaster in a rented 28-foot trailer. Table I shows some of these new loads. The data is suggestive, not conclusive. But three-shot strings are enough to sift out loads on the ends of bell curves – velocities too low, pressures too high, standard deviations excessive, groups abysmal. Dispensing with those, I usually follow with five each of promising loads. Time is precious, primers are still in hiding and powder is no longer $1.50 a pound.

Oddly enough, Remington’s Depression-era Model 30, arguably its first commercially successful bolt rifle, was not barreled to 270 Winchester. In 1948, Remington acknowledged the error of its ways and barreled its Model 721 in 270. The 270 would remain a popular chambering in its offspring, the Model 700. Savage has sold its Model 110 in 270 since the rifle’s 1958 debut. Legions of 270 bolt rifles, foreign and domestic, have followed. Remington introduced its slide-action Model 760 in 270 in 1958. Remington and Browning have peddled 270 autoloaders, Ruger and Browning 270 single-shots while Browning offers a lever-action.

I’ve found most 270 rifles shoot acceptably well with all traditional bullet weights – not just 130s and 150s, but Nosler’s fine 160s and the crop of 140s that have relieved us all of having to weigh, in our sleep, the virtues of bullets 10 grains lighter against those of bullets 10 grains heavier. I’m convinced if you wish to shoot 100-grain bullets, you’re best served by a 25-06 – even by a 243 Winchester. But to give the 270’s lightest common bullet its due, I fired a few 100-grain Remington loads through my Marlin X7 bolt rifle. Listed at 3,320 fps, they delivered an impressive 3,366 fps average velocity over my chronograph – and this from a 22-inch barrel. They printed a .75-inch group. Clearly, these bullets like the rifle’s standard 1:10 twist. (Husqvarna rifles have 1:9.5 twist, Mannlicher-Schoenauers are 1:9.)

.jpg)

While many powders have been listed for the 270, I’ve had consistently high-velocity readings from powders with burn rates bridging those of IMR-4350 and H-4831. I avoid powders so slow and bulky that they beg compressed charges. I’ve nothing against modest compression, as when charges climb into the base of the neck. But crushing powder can alter its burn rate.

Nearly all bolt-action sporting rifles barreled to 30-06 have now been offered in 270. Case dimensions below the shoulder are the same, so too the overall lengths. Magazines that work for one should work for the other. In sum, a barrel is the only difference. Any rifle listed in 30-06 should be offered in 270 too!

I came by the 270 long ago, in a swap for a Henriksen-stocked Mauser. It blessed me with deer, elk and my first bighorn ram. Other 270 rifles have come and gone. How any got permission to leave is beyond me. They were all fine companions, easy to carry and to shoot well. A forever favorite is a Model 70 of late-1940s manufacture, with fencepost wood, cracked recoil pad, age-silvered steel and many scars. Its price at a long-ago gun show reflected its cosmetic mediocrity, not its bright bore or buttery bolt travel. On a frosty morning above timber months later, I spied antlers 300 yards across open talus. Snugging the sling, I sat, nudged the 3x Lyman’s crosswire a hand’s width high and sent a Speer 130-grain through the vitals. When I hunt deer with other rifles now, I always wonder why.

But I have used others, including the accurate Bergara and Cooper rifles that fired the handloads featured here. I’m sweet on Tikka’s T3, Remington’s pre-Cerberus 700 Classic, Kimber’s Classic Select 94L and Ruger’s 77 RS (discontinued). Also, semi-custom rifles like those from H-S Precision. A couple of years ago, I met a hunter with a very early Savage 110 in 270. Checkered walnut, open sights. It came nicely to cheek; the bolt ran piston-smooth. It was listed in 1959 for $109.75.

More recently, in a used-gun rack, the 20-inch barrel of a Remington 700 caught my eye. It was a 270. Months after its 1962 debut, 20-inch barrels on standard 700s had given way to 22-inch. The stock on this rifle was battered but unaltered. I dug for my billfold. Carefully refinished, the wood now looks very nice, and I’m awaiting an aperture sight for this 270 “carbine.”

Did I need another 270? No. Can anyone ever have too many 270s? No.

.jpg)