A "CHEAP" Benchrest Rifle

Ten Years of Tweaking the 6mm PPC

feature By: John Barsness | March, 22

I don’t know where this notion originated, but Noah Webster published his first dictionary in 1828, based on “common use” – what most Americans mean by a word. Most shooters use accuracy when discussing small groups, an example of “common use,” and today’s major English dictionaries back up such common shooters. Both a recent Webster’s unabridged and the British Oxford Dictionary of the English Language list “accuracy” as a synonym for “precision,” and “precision” as a synonym for “accuracy.”

Humans have been looking for finer accuracy since we started flinging rocks, arrows or bullets. Spiral rifling was developed 500 years ago, partly because arrows flew straighter if they spun during flight, due to angled fletching. Rifling similarly resulted in far finer accuracy than smoothbores.

My first attempt at improving accuracy was resting the Daisy on a small cardboard box placed on my family’s backyard picnic table. (Backyard BB shooting was then legal in our Montana town.) This “benchrest” helped, though not at long range, such as the 60 feet to the sandbox.

Soon this led to iron-sighted rimfire rifles, then my first scoped centerfire rifle and handloading. In my 20s, I started writing professionally, at first about any subject somebody paid me for. After a decade this included a little “gun writing,” and my accuracy obsession increased, a natural progression when you’re paid to obsess.

Back then, the primary handloading advice involved testing several different bullets and powders, to discover which my rifles “liked.” In my mid-20s, this worked very well on a new rifle, a Remington 700 ADL .270 Winchester. After bedding the action and free floating the barrel, I discovered that Hornady 150-grain Spire Points and “war surplus” H-4831 resulted in three-shot, 100-yard groups, which often had the bullet holes touching and at 300 yards averaged around an inch.

However, a decade later, I learned the major reason was not that my rifle “liked” 150-grain Spire Points. Instead, the seating stem in my RCBS die closely fit the “spire.” Hornady Spire Points have what gun writer Elmer Keith called a “pencil point,” formally named a secant ogive. This is less curved than the tangential ogive used on most hunting spitzers, and tangential ogives did not fit the seating stem as well. The Hornadys seated straighter, so entered the rifling straighter than other bullets – a major factor in accuracy.

This was discovered after RCBS sent me a Casemaster, a “concentricity gauge” indicating how straight bullets are seated compared to the case body. I started using the Casemaster when developing all rifle handloads, which helped – but it wasn’t the only answer. Some bullets refused to group well, due to some bullets being better balanced than others.

Within a decade, my research involved loading techniques used by benchrest shooters, as described in the magazine Precision Shooting and books by writers from Townsend Whelen to modern winners of major matches. This resulted in the revelation that few factory hunting rifles were sufficiently accurate to demonstrate how each part of the handloading process affected accuracy. They all shot more accurately with consistent handloads, but none came close to the tiny benchrest groups shown in magazines and books.

The next step occurred in 1994, while attending the annual Groundhog Shooters and Prevaricators Conference on a former 800-acre farm in West Virginia. Each year, Melvin Forbes of New Ultralight Arms, invited several firearms folks to shoot groundhogs (woodchucks), prevaricate (lie) and talk guns. One was the late Mickey Coleman, a benchrest gunsmith who introduced me to his personal 6mm PPC rifle and several sophisticated wind flags placed between the bench and target. Within half an hour I started shooting “photo” groups!

However, my gun writing income wasn’t enough to justify a real benchrest rifle, so instead I bought a new Remington 700, a heavy-barreled varmint model in .223 Remington. Out of the box, it grouped five handloads into around .75 inch, but after “accurizing” the rifle, mounting a 6-24x Bausch & Lomb scope and assembling ammunition with benchrest techniques, the .223 consistently grouped five shots in around .25 inch at 100 yards – on calm mornings using homemade wind flags.

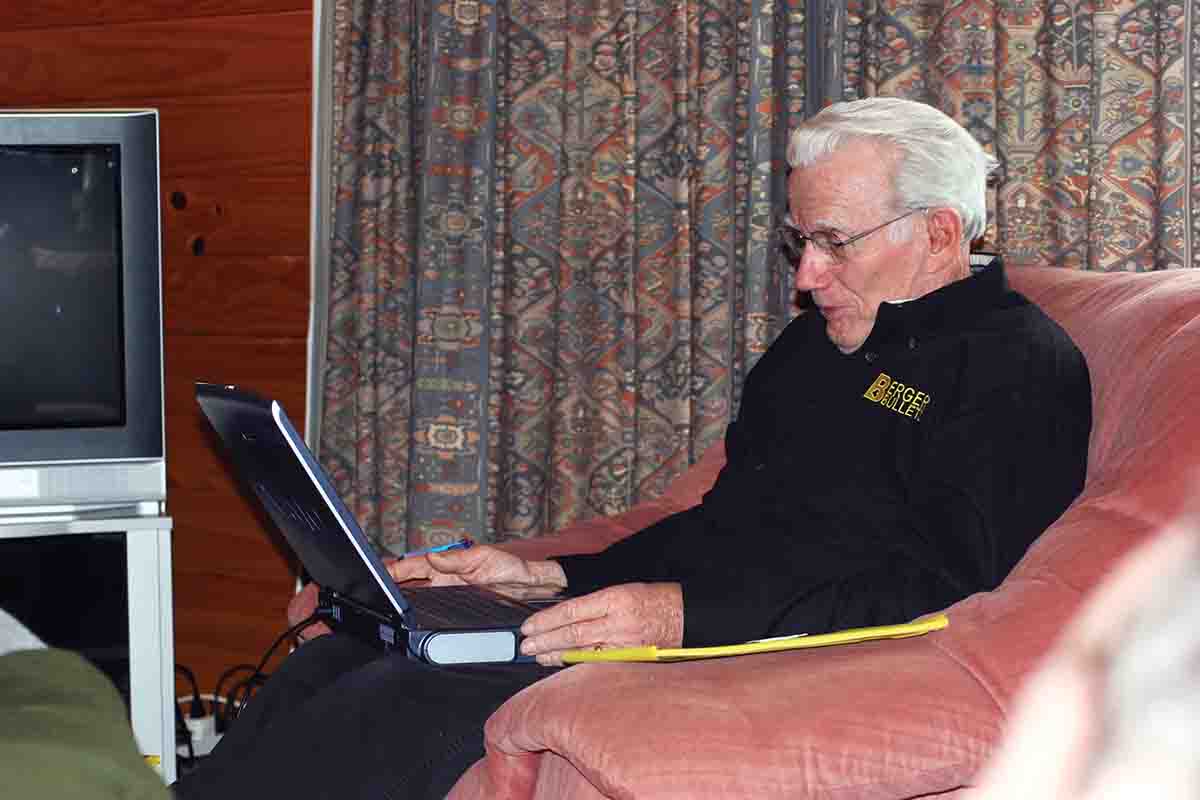

This satisfied my obsession for a while, but real benchrest rifles need to group five shots in “the ones,” as benchrest guys put it, meaning under .20 inch. Through my writing, I got to know several big names in benchresting. Among them were bullet maker Walt Berger; Allan Hall, who started building his fine benchrest actions and rifles in 1977, and Kenny Jarrett, known among hunters as a maker of super-accurate “beanfield” deer rifles.

Eventually, I started seriously thinking about ordering a custom benchrest rifle, but in mid-2011, I found one on the used rack at Capital Sports in Helena, Montana. It had a stainless steel barrel measuring almost an inch in diameter, a green metal flake synthetic stock and a Remington 700 action encased in a thick aluminum “sleeve,” firmly epoxied into the stock.

One suggestion encountered during my benchrest reading was NOT having a local gunsmith build a rifle. Instead, hire a real benchrest gunsmith like Mickey Coleman, Allan Hall or Kenny Jarrett to put it together, preferably on a specialized action like a Hall.

However, I knew Arnold was far better than most “local” gunsmiths. Among other things, he built excellent custom rifles from flintlocks to modern big-game guns, and another of my rifles purchased at Capital was an old Marlin lever action, originally a .30-30. Arnold had rebored and rechambered it to .38-55, and it shot very well.

The price of this 6mm PPC was a fraction of what a new bench rifle would cost, so I returned the next day with my Gradient Lens borescope. The inside of the barrel looked almost new, so the 6mm PPC left with me.

I had no desire to compete in benchrest matches, due to primarily being a hunter. Competing would take time away from my year-round hunting! Instead, I wanted to isolate the factors in accuracy handloading, so I decided to use tools handloading hunters use, rather than specialized benchrest tools.

Redding provided a set of its Competition “bushing” dies and 100 Norma 6mm PPC cases. I sorted the brass by weight, then neck-turned the most consistent 50 cases so loaded rounds would fit the chamber. Instead of a benchrest-type hand tool, I used the neck-turning attachment for my old Forster case trimmer, and “uniformed” the primer pockets and flash holes.

Match results in Precision Shooting indicated the primary powders preferred by 6mm PPC competitors were Hodgdon H-322 and Vihtavuori N133, though other powders occasionally appeared. However, this was during the middle of the “Great Obama Shortage,” and no VV-N133 could be found, but I had some H-322, and varying quantities of other suitable powders, including Benchmark. Many competitors used Federal 205 Match primers, and I had plenty on hand. MidwayUSA provided one of its Caldwell Rock BR Competition front rests, and Walt Berger sent some 62-, 65- and 68-grain target bullets.

It should be mentioned that typical “short-range” benchrest shooting at 100/200 yards runs contrary to the present trend of faster rifling twists, to shoot heavier boat-tailed bullets with high ballistic coefficients. Instead, the finest accuracy at those ranges occurs with relatively light, flatbase bullets shot through rifling twists just enough to stabilize them – which is why my rifle’s Hart barrel has a 1:14 twist.

I mounted a 30mm-tubed, 4.5-30x Bushnell Elite 6500 scope in Talley steel rings, bringing the weight to 13.5 pounds – the weight limit for the Heavy Varmint class in short-range benchrest shooting. Neither scope nor mounts is conventional among benchrest shooters, who tend to use fixed-power scopes of somewhat higher magnification, often with adjustments “frozen” to prevent shifts in point of impact. Kenny Jarrett recommends steel Talleys for his big-game rifles.

The 25.5-inch barrel is also longer than is fashionable. Most new benchrest 6mm PPCs have shorter barrels, because that makes them stiffer. I am guessing Arnold left it long so the barrel could be set back and rechambered after the throat eroded too much, and I might ask him next time we run into each other. He “retired” from Capital several years ago, but still makes a rifle now and then.

The first range-session “fireformed” the new, uniformed brass, using the three Bergers and a starting load of Benchmark, primarily because I had more Benchmark than any other suitable powder. Bullet runout on my Casemaster maxed out at .03 inch, which is okay for varmint rifles but not benchrest rifles. The breeze measured from 1 to 2 mph on my Minox Wind Watch, and I did not use wind flags – though I did experiment with shooting styles.

Some benchresters only touch the trigger, allowing the rifle to recoil freely on its rests, while others hold the rifle gently but conventionally. I played a little with only touching the trigger, but decided that a conventional hold would better match my test purposes.

Sighting-in and nine, five-shot groups resulted in 50 fireformed cases. The groups averaged .551 inch, about like good factory ammunition in the heavy-barreled Remington .223 – but this was just the start.

The fireformed cases were then neck-sized with a bushing just small enough to hold bullets firmly. Runout on the Casemaster’s dial was almost nonexistent, at most about half the .001-inch markings. With most rounds, the needle barely quivered.

I loaded charges up to 31 grains of Benchmark in half-grain increments. The 65-grain bullets had shot the smallest groups, so I decided to retry them, using two different seating depths, just off the lands and firmly touching the lands.

Most benchresters report finding the best accuracy with bullets contacting the lands in various degrees – which occurred in my rifle as well. The first two loads listed in the table are with the bullets either contacting the rifling (2.085 inches overall length) or just off the lands (2.083 inches overall length). The difference in accuracy is obvious.

The loads were shot on a near-calm morning, using wind flags made by the Australian firm Bench Rest Tactical, obtained from Shade Tree Engineering and Accuracy (shadetreeea.com), the website of Butch Lambert, a benchrest gunsmith in Texas. The most accurate powder charge turned out to be 30 grains, which is over maximum according to most published data. However, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) does not list any pressure standards for the 6mm PPC, and many benchrest competitors use “warm” handloads, partly because they tend to shoot more accurately, and partly because extra muzzle zip reduces wind drift. Further experimentation found Benchmark to be the most accurate powder in my collection, with five-shot groups averaging .181 inch – in the “ones.”

I also wanted to use the rifle for prairie dog shooting, so I tried several varmint bullets with different powders, seating the bullets just off the lands. “Jamming” target bullets works okay in benchrest shooting, because any time a round is chambered, it gets fired. In prairie dog shooting, however, shooters sometimes don’t fire a chambered round – and the barrel can be pretty hot and fouled. This can result in a jammed bullet sticking in the lands during ejection. Seating bullets a little off the lands prevents such disasters. None of the varmint bullets shot as well as the 65-grain Bergers, of course, but 55-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips grouped best.

In 2016, this load was used on a prairie dog shoot with several friends in central Montana, and worked very well to around 550 yards, my longest shot, partly because the Bushnell’s adjustments are very repeatable. However, I didn’t want to wear out the barrel shooting varmints, so only shot until the barrel got slightly warm before switching to my “normal” prairie dog rifles – and haven’t hunted with the rifle since.

Some “custom” 66-grain bullets many competitive benchresters used at the time were also tested. I will not name them, but note (as the table indicates) that they didn’t shoot as well as the Bergers.

These days, the rifle gets used to test new powders, or other components. Note some of the test results in the table, along with the year of each. As a result, its “best” load improved. Right now it uses Accurate LT-32 instead of Benchmark, and Sellier & Bellot Small Rifle primers rather than Federal 205Ms.

However, Berger recently discontinued the 65-grain flatbase, so I decided to retry the 68-grain bullets, due to finally obtaining some Vihtavuori N133. The trial started with the bullets seated .002 inch off the lands, to get some idea of velocity and hence pressure.

Somewhat oddly, each of the two, five-shot groups had one obvious “flier,” with the other four shots averaging in the “mid-ones.” Was this due to the “short” bullet seating or me not having pulled the 2-ounce trigger for a while? I have been too busy hunting and handloading for big-game rifles to find out, but intend to when time and conditions allow. There are always new accuracy questions, which often get new answers, but what I do know is that my affordable and “unfashionable” benchrest rifle still shoots very well, even after a decade of tests.

.jpg)