Winchester's .38 WCF (.38-40)

Loads for Vintage Rifles

feature By: Mike Venturino, Photos by Yvonne Venturino | March, 22

To me, the truly perplexing thing about the .38-40/.38 WCF is why it was developed at all. It was introduced with lead bullets weighing 180 grains of .400-inch diameter. Winchester already had the .44 WCF/.44-40 on the scene for several years. It fired a 200-grain lead bullet of .425 inch. By its own 1899 catalog, velocity of the two were 1,268 feet per second (fps) for the .38 and 1,245 fps for the .44. Both specifications were from 24-inch barrel lengths. Since when in anyone’s logic, even in the 1870s, does 20 grains of bullet weight and about 25 fps of velocity count for much in the field? Regardless, Winchester introduced its .38 WCF as the second cartridge for the extremely popular Model 1873 lever gun in 1879. Some sources list 1874 as introductory .38 WCF date, but 1879 is authoritatively stated in THE WINCHESTER BOOK by George Madis as the proper year. That book also stated that a mere 18 Model 1873 .44s were actually sold in its year of introduction.

Winchester’s Model 1873 stayed in its catalogs around a half century. Again, according to Madis, manufacture of ’73s ceased in 1919 and sales stopped in 1924. There was a short hiatus of production during the American involvement in World War I. More than 720,000 Model 1873s were sold, which is impressive considering the much smaller population worldwide in that time frame.

In the above mentioned Winchester 1899 catalog, the company gave evidence of what the company considered proper ammunition for its “pistol cartridge” lever guns. Therein, the ’73’s performance is touted with black- powder loads. No mention is made of smokeless propellant, which by that time, Winchester was loading in many cartridges. However, in the Model 1892’s catalog section, smokeless loads were promoted along with the black powder ones.

Personally, I have to laugh when reading Winchester’s claims about its “pistol cartridge” lever guns. With the ’73, it rates the .44 as accurate to 300 yards and “sufficiently powerful to kill bear, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, etc.” However, the claim for .38 is reduced, stating “This cartridge is heavy enough to kill deer and small game and is accurate up to 300 yards.” I guess that extra 20 grains of bullet weight, .025 inch in bullet diameter and about 25 fps of velocity counted for something to the catalog’s authors. And 300 yards? I have a steel target 24 inches tall and 18 inches wide at 300 yards. It is difficult to hit with vintage Winchesters and their factory sights.

As for details such as barrel lengths, sights, stock configuration and even price, Winchester tried to keep the ’73s and ’92s comparable. Standard rifle barrel lengths were round, 24 inches long. Octagonal barrels cost $1.50 more. Carbine barrels were lightweight, round and 20 inches in length. Standard rear sights were buckhorns for rifles with a notched slider for elevation change. Carbine rear sights were ladder style: simple notched leaves when sights were down, with another sliding notched leaf when raised. Both model’s rear sights were dovetailed to barrels and could be drifted for windage adjustment. Rifle front sights were blades and also dovetailed, but carbine front sights were blades inset in a lug brazed to the barrel behind front barrel bands. Something Winchester could not match between the two models was weight. Model 1873 rifles weighed 8¾ pounds but Model 1892 rifles were only 6½ pounds. Carbines were 7¼ and 5¾ pounds in the same order. Model 1873 and Model 1892 standard rifles were priced $18.00 in 1899 and carbines were $17.50.

Winchester ’73s, through most of its production run, offered .32, .38 and .44 WCF as chambering options. According to THE WINCHESTER BOOK, about eight of every 10 made were .44s, and .32s outsold .38s by a factor of four to one. I’ve found .38-40 ’73s and ’92s much easier to find than the other chamberings. In my collection is a round barreled Model 1873 .38-40 rifle, which in 1985, I bought from Steve Garbe, editor of Wolfe Publishing’s The Black Powder Cartridge News. It has stuck because of its fine accuracy, albeit its exterior finish shows considerable wear. It was made about 1900.

In regard to Model 1892s, I also own two .38-40s. One is a .38-40 saddle ring carbine made in 1909. (Winchester dropped saddle rings on its carbines circa 1927. Horseback travel was pretty much over by then.) The other is a round barreled Model 1892 .38-40 rifle that had been a Christmas gift from a friend. That ’92 rifle was expertly refinished somewhere since being made in 1914. However, it is also finely accurate so it was included. Please note that no modern-made replica .38-40s were used herein. That’s because they are few in number. To the best of my knowledge, the only Winchester levergun replicas chambered for .38-40 currently are from Uberti of Italy and cataloged by Cimarron Arms. I owned one once and it too was a fine shooter, but just try to find one now.

.jpg)

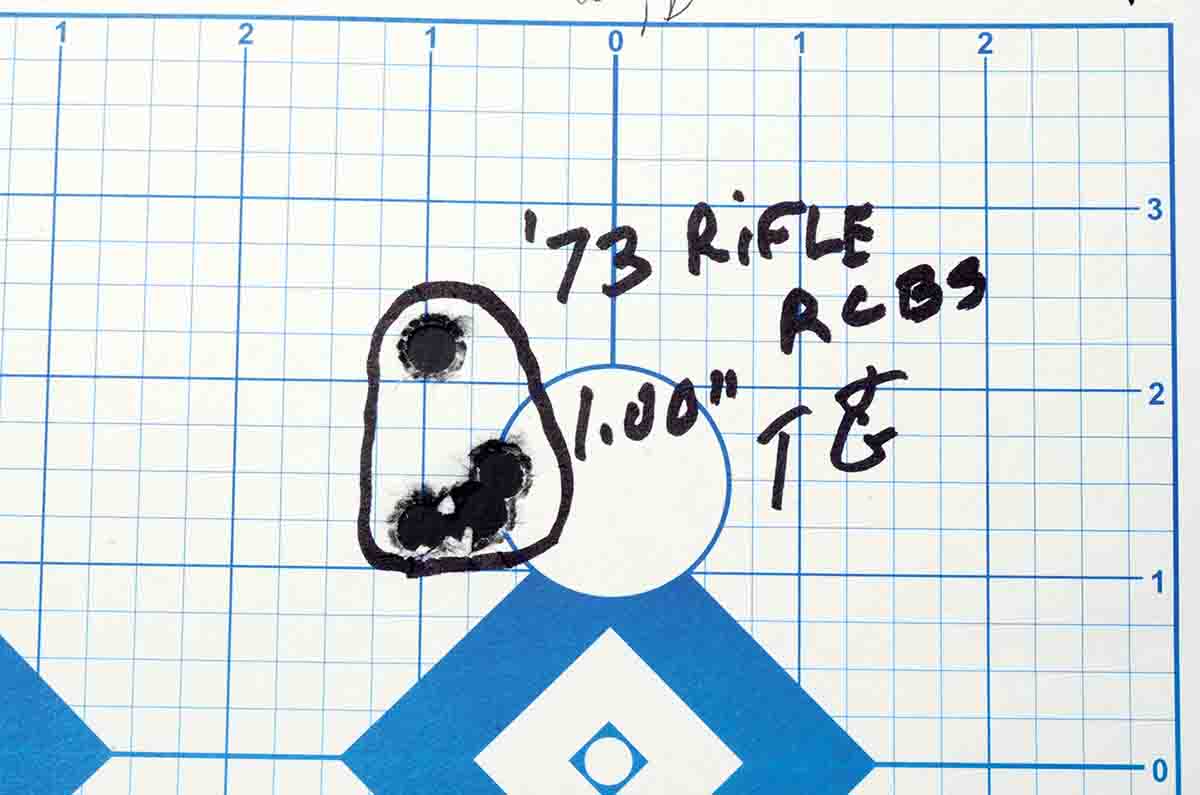

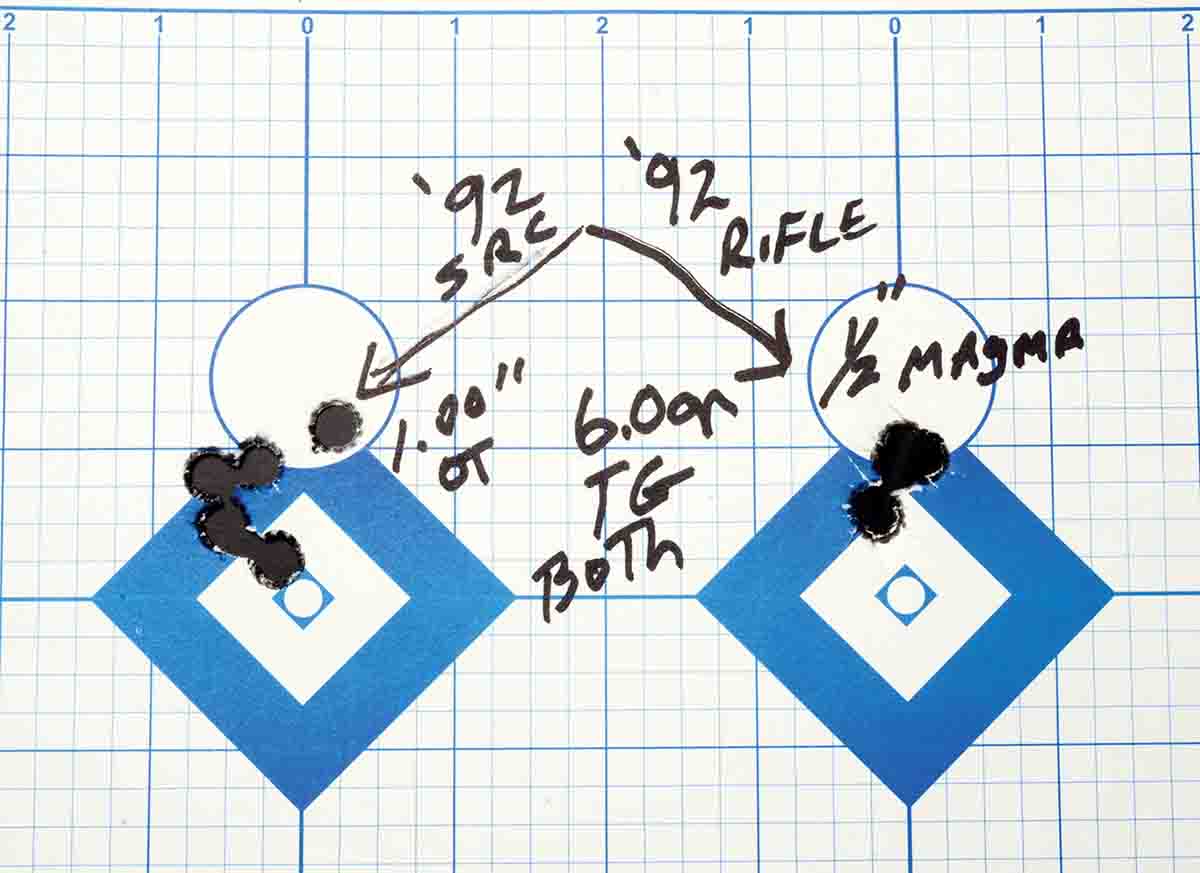

By the way, a few times, a single flyer ruined an otherwise near one-hole group. I’ve noted that in the accompanying table. My inclination is to blame myself for said flyers. If four bullets cut the same hole with a flyer out a bit, it’s likely that is a good load regardless. As the accompanying table shows, all groups, including flyers, were averaged per rifle/carbine, bullets and powders.

Bullet moulds for .38-40 are not all that common today. RCBS lists in its cowboy mould section, a double-cavity 40-180-CM. It’s a fine RN/FP design, falling from the mould at .401 inch and weighing 180 grains when poured from 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy. Also on hand is a Magma double-cavity mould numbered 38-40, 180 grain, RN/FP with a bevel base. Magma moulds are meant for casting machines but can be converted to hand casting with a kit from Accurate Molds of Salt Lake City. My Magma 180 RN/FPs fell from the mould at 183 grains. My only complaint is that when a soft bullet lubricant is applied, it gathers on the bevel, requiring removal from each one.

When ordering Accurate Molds’ kit for converting Magma moulds to hand casting, I checked its list of 700 possible bullet designs available on a custom order basis. At its 40-175H, I stopped and placed an order for a triple cavity mould of iron, which is my favorite configuration for casting handgun-size bullets. Bullets from it are also RN/FP and weigh 180 grains of 1:20 alloy. To top out the matter, I also found in my bullet stash, a partial box of Oregon Trail’s 180 grain RN/FP, which are actually the same design I cast myself with the Magma mould. Oregon Trail uses a hard alloy, so the bullets actually weigh 177 grains. Unfortunately, there were only enough of these to use with two propellants.

By this point, some readers are thinking, “Mike, why don’t you use some of the moulds intended for .40 S&W and 10mm Auto? They drop bullets of similar size and weight as dedicated .38-40 moulds.” The problem there is the crimping groove. Without one, levergun magazine springs will force bullets down in the cases atop powder charges. Incidentally, all Winchester pistol cartridge leverguns require a loaded cartridge overall length of 1.592 inches, maximum. The bullets described in these paragraphs fit that parameter. Also, all rounds fired were loaded into and fed from the magazines so as to make sure all functioned properly.

There is one point about case sizing needing attention. My 1983 vintage RCBS dies size cases back to nominal dimensions perfectly. However, if there is the slightest excess lube on cases, they dent severely at the junction of case neck to shoulder. In another firing or two, cases split at the site of that dent. With liquid case sizing lubricants, I developed the habit of smoothing that area with my fingers prior to sizing. That reduces dents by about 95 percent. Using the Lee lube, which turns into powder after drying, also alleviates the problem, if it is allowed to dry completely before use.

Only four powders were chosen for this project: Trail Boss, Titegroup, W-231 and Unique. Sharp-eyed readers might note that all the charges per each type of propellant were the same for all bullets. Again, I think readers may ask, “Why not vary powder charges to see if a half grain or so might group smaller?” My reasoning is this. The powder charges used were near what I predetermined were maximum for my 100-year-plus vintage leverguns. My actual quest was to find which bullets would perform best, i.e. most accurately, with my chosen powder charge weights.

A careful look at the load table will show that the overall best groups came with Titegroup with a charge weight of 6 grains. Only a few groups with it and all bullets measured over an inch. The two best groups of 45 fired measured a mere half-inch. One was shot with the Model 1892 rifle using Titegroup with my home-cast Magma bullets. The gentlest loads used Trail Boss powder and the highest velocities came with Unique.

As perplexing as the .38-40 might be, and as unneeded as it might have been, except for those of us fond of vintage Winchester leverguns (especially those chambered for pistol-size cartridges) it is highly respected.

.jpg)