Johnson's 22 Spitfire in the M1 Carbine

3,000 fps in a Pistol Cartridge?

feature By: Art Merrill | July, 25

The M1 Carbine presented here first came to me needing a chamber cast, as the baffled owner pointed out that the bore is obviously smaller than .30 caliber, and the barrel has no stamp indicating its chambering. A chamber cast of Cerrosafe and careful measurement with a caliper confirmed my guess that the carbine is chambered in 22 Spitfire. About a year later, the non-handloading owner, knowing of my interest in esoteric and arcane rifles and cartridges, offered to sell me the carbine at a price I couldn’t refuse.

This is a “commercial” carbine manufactured by Rock Island Armory, one of many companies that made M1 Carbine clones for civilians after World War II. Rock Island Armory was a privately owned company that borrowed its name from the U.S. Government’s Rock Island Arsenal. Perhaps not coincidentally, the company located manufacturing just a few miles away from that government arsenal in Illinois. Rock Island Armory was in the business of selling milsurp firearms and parts, and manufacturing the M1 Carbine clone, from 1979 to 1985; it is not associated with today’s Rock Island Armory, owned by Armscor in the Philippines, which acquired the name some 20-odd years after the Illinois company shut down.

Overall, while the receiver, trigger guard group, and handguard are immediately recognizable as an M1 Carbine, the stock is decidedly un-military, as is the scope mount and front sight. The stock configuration is a classic hunting rifle, featuring a Monte Carlo cheek rest, slim wrist with pistol grip, cut checkering and a (completely unnecessary, given the cartridge) ventilated rubber recoil pad. White line spacers add a little fashionable flash. The wood has the straight grain of typical American walnut, with an oil finish. The handguard is a bit of a mismatch, not so much because of the color, but because it wears a different finish, probably varnish. The back end of the handguard is slightly relieved to accommodate the Redfield scope mount.

Stampings on the receiver ring read, “CARBINE CAL 30 M1,” indicating it was manufactured for that cartridge, not the 22 Spitfire. On the receiver rear, “ROCK IS. ARMORY C9” clearly identifies this as a commercial variant of the M1 Carbine. The C9 serial number indicates this was among the first 500 carbines Rock Island Armory manufactured. Research, however, has not definitively discovered whether the company chambered any carbines in 22 Spitfire. Another indicator that this carbine was later converted to a 22 Spitfire is the different finish on the barrel and receiver. Rock Island Armory is known to have Parkerized its receivers, and indeed, this one appears to bear that iron oxide finish, in black. It’s reasonable to expect barrels, too, would have been Parkerized, but this one is blued, a clue that barreling to the present caliber likely occurred outside the factory. Indeed, Rock Island Armory did sell receivers alone, and Numrich Gun Parts used to offer 256 Johnson (22 Spitfire) barrels for sale.

In addition to a properly chambered barrel, converting the M1 Carbine to 22 Spitfire also benefited from modifying the feed ramp, typically (or at least on early conversions) by brazing or welding it into the receiver, to reliably feed the smaller-bulleted, bottleneck cartridge from the standard M1 Carbine magazine. This receiver does not have a modified feed ramp, and 22 Spitfire cartridges failed to feed from the magazine when hollow-point bullet noses banged against the barrel breech face to cause a stoppage. Pointed and some semipointed bullets fed reliably, but lead and polymer bullet noses suffered some “shaving” as they skimmed across the breech face edge when chambering. This, too, is a pretty good indicator that the 22 Spitfire barrel fitting is a post-factory job.

Here is a good place to address the cartridge designation. Originally developed about 1962 as the MMJ 5.7mm by its creator, Melvin Johnson (yes, the same USMC Col. Melvin Johnson of 1941 Johnson Rifle and Johnson Light Machine Gun fame), this 30 Carbine cartridge necked down to take a .223-inch bullet is saddled with a confusing cornucopia of names, including 5.7MMJ, 5.7 Johnson, 5.7mm Johnson, 5.7mm Spitfire, 256 Johnson, 22 Johnson Spitfire, 22 Spitfire, 22/30, 22/30 Carbine, 22 Carbine, 22 M1 Carbine and 22 PMC. (The latter references the Plainfield Machine Company, which manufactured commercial M1 Carbines from about 1962 to 1978 and attached its company initials to the .22 caliber cartridge, probably to avoid a trademark issue.) There may well be others.

Johnson’s original idea was to inexpensively improve the government’s huge inventory of post-war M1 Carbines by converting them to fire a high-velocity .223 caliber bullet. Some posit that Johnson thought his cartridge and carbine conversion to compete with the 5.56x45 NATO cartridge and M16 rifle was already on its way toward government acceptance. However, according to his son, Ed Johnson, Melvin Johnson intended the cartridge and carbine to replace the M1911A1 pistol and its 45 ACP cartridge.

Lacking military interest, Johnson instead started his own civilian company in 1962 called, creatively enough, Johnson Guns, Inc., which modified milsurp M1 Carbines to fire his renamed 5.7mm Spitfire cartridge from his own M1 Carbine conversion, the Johnson Model JSM 5.7mm Spitfire Rifle. The company suffered financial difficulties, Melvin Johnson died of heart failure in 1964 and Johnson Guns, Inc. reformed under the name Johnson Arms, Inc. Eventually, at least four models of the converted carbine were offered, including the “Johnson MMJ™ 5.7/mm Deluxe Sporter Spitfire,” but the company folded permanently by 1967.

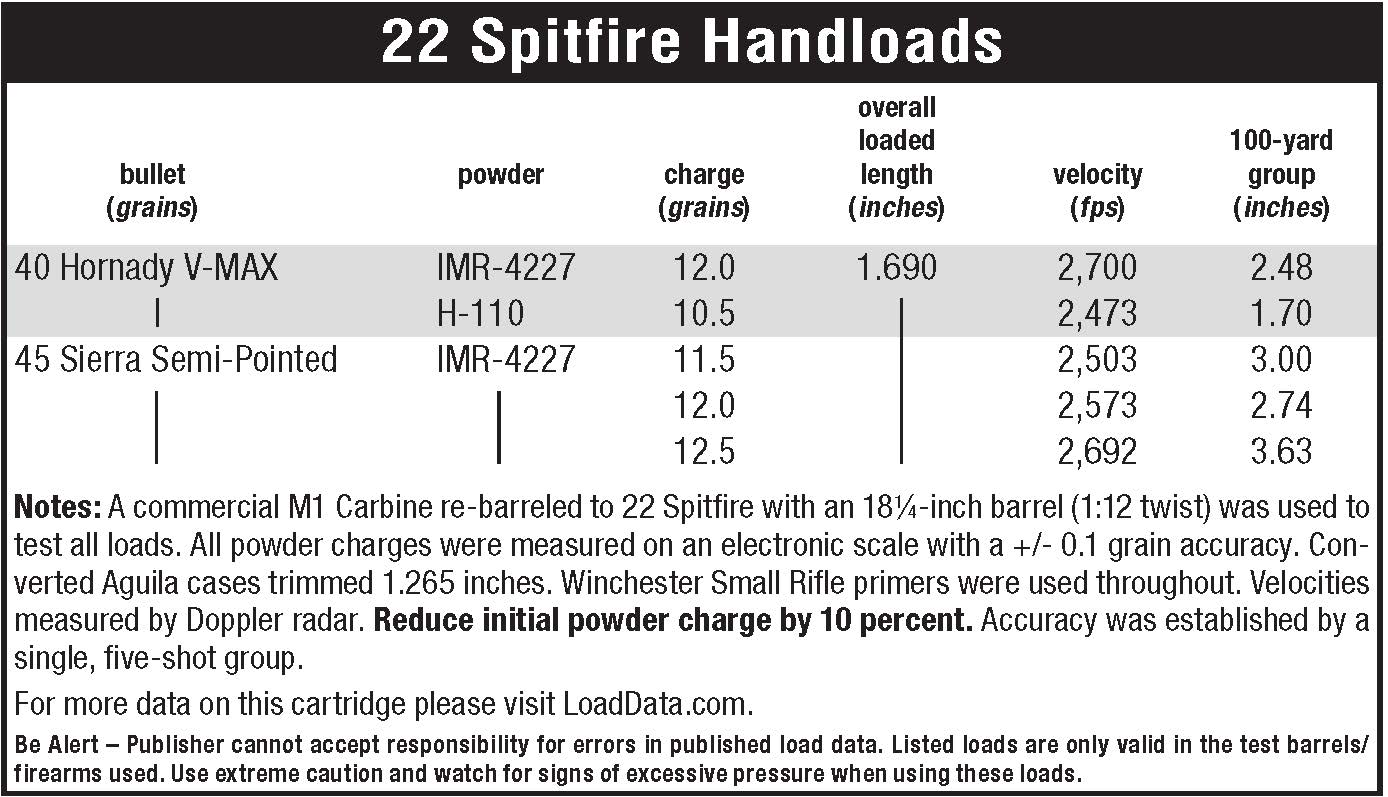

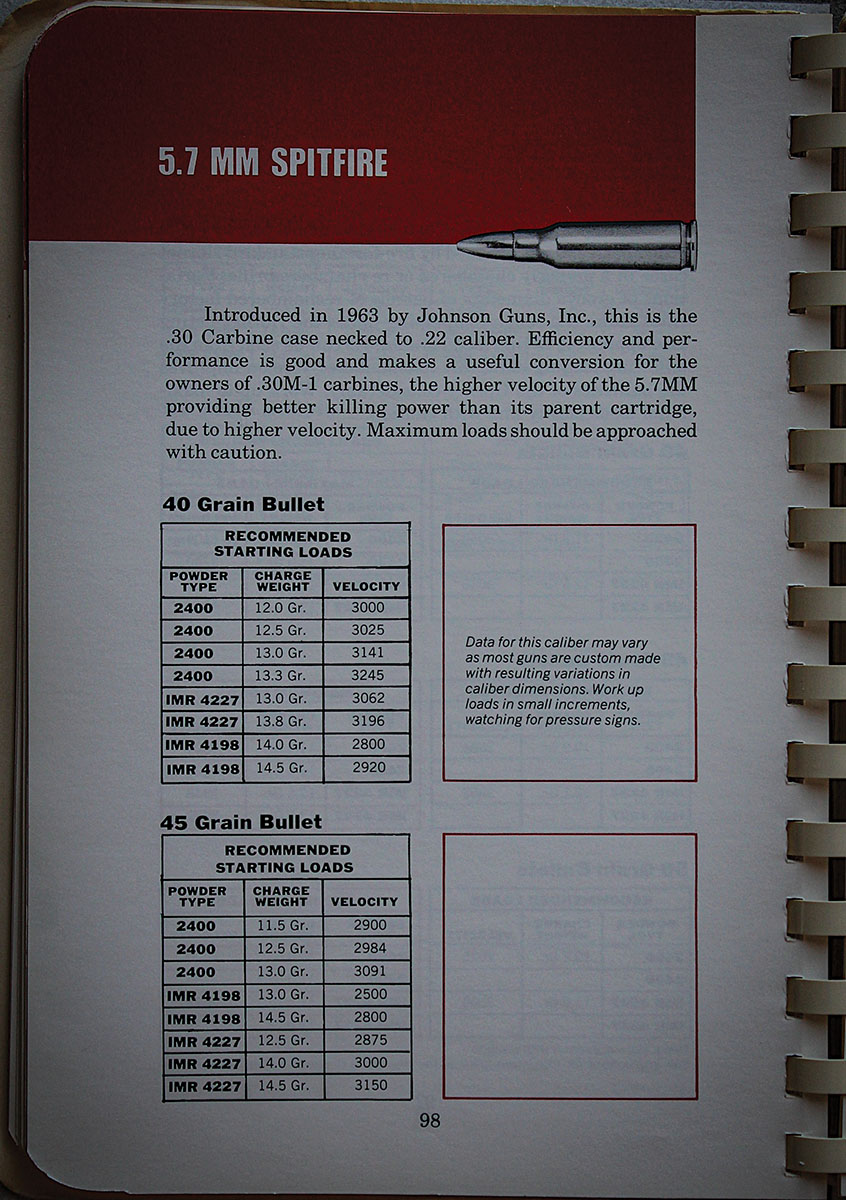

Johnson’s wildcat is a cartridge that should have succeeded, but if you aren’t old enough to have watched Walter Cronkite narrate the first moon landing live on TV, it’s pretty likely you are unfamiliar with the 22 Spitfire. Period magazine advertisements claimed 2,700 feet per second (fps) for a 40-grain bullet, but the Pacific handloading manual Second Edition rockets that bullet, with a starting load up to 3,245 fps, and a 45-grain bullet at 3,150 fps. I found both of these latter Jack-the-Giant-Killer claims to be not safely attainable, but the 22 Spitfire does make advertised velocity with only about half the powder needed for a 223 Remington. It does this below the 30 Carbine’s maximum pressure of 40,000 psi, compared to the 223 Remington’s 55,000 psi. Combine that with its negligible recoil, and we have a true sleeper of a modern high-velocity cartridge in a small package. The cartridges overall length is significantly less than that of the 223 Remington and almost identical to the newcomer 5.7x28 cartridge.

SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) never set a pressure or chamber standard for the cartridge, which prompts a caution for would-be handloaders. Because there is no standard, cartridge case and die dimensions will likely differ among manufacturers, and so too may chamber dimensions among the various conversions. Even bore diameters might differ slightly, as some barrels were intended for .224-inch bullets, and others for .223-inch bullets. Either Johnson or handloaders in general settled on an optimum load of 11.5 grains of IMR-4227 under a 40-grain flatbase, spirepoint bullet. In perusing the handloading work of others, powders with burn rates between Alliant 2400 and IMR-4227 seemed to get the best results. Slower powders perhaps tend to burn incompletely in the short M1 Carbine barrel, whereas with faster powders, cases begin to show overpressure signs before getting up to velocity.

Handloading the 22 Spitfire is not an endeavor for the penny pincher, as it will require custom reloading dies. Lucky me, the M1 Carbine here came with a set of old Eagle brand reloading dies stamped. “22 Carbine” and 64 handloaded rounds formed from mixed headstamp milsurp .30 Carbine brass. Following the safety rule to never shoot handloads from others, I pulled the bullets and discarded the powder and primers to make my own preliminary loads from the brass.

Rifling in this 18¼-inch 22 Spitfire carbine barrel has a 1:12 twist rate, theoretically optimal for 55-grain bullets launched at 3,200 fps, a combination not safely workable given the powder space available in a .30 Carbine case. After loading dummy rounds with a variety of bullet configurations to check for feeding issues, I crunched successful candidates through Berger’s online twist rate calculator BergerBullets.com/twist-rate-calculator/, which advised Berger’s 40-grain Flat Base Varmint bullet would be “comfortably stable” from 1,600 fps and beyond in that 1:12 twist. Unfortunately, Berger’s bullet is one that won’t feed from the carbine’s magazine. Hornady’s 40-grain V-MAX bullet feeds from the magazine but needs 3,000 fps legs to be even “marginally stable,” according to the calculator, but I included it with a dash of hope. Sierra’s 45-grain semi-pointed bullet also fed from the magazine, and so it made the cut for the experiment.

As you can see in the accompanying table, the 40-grain bullet did best when launched considerably below the original 2,700 fps claim. Groups with 45-grain bullets opened up as velocity increased, and cases started showing flattened primers before suddenly suffering a case head separation beyond the 12.5 grains of IMR-4227 shown in the table. As noted earlier, there is likely a disparity between sizing die and chamber dimensions, promulgating the case head separation. In reality, Johnson’s cartridge (safely loaded for this M1 Carbine, anyway) is about on-par velocity wise with the 22 Hornet and perhaps the 22 K-Hornet.

The latter may be the real reason Johnson’s cartridge never caught on. One might chamber a good bolt-action or single-shot rifle in 22 Spitfire to edge up toward 3,000 fps and varmint accuracy out to 200 yards, but with so many other cartridge choices available, it would be difficult to justify the expense, beyond satisfying curiosity.

Sometimes, however, that’s reason enough, and satisfying curiosity is pretty much the reason I bought this World War II carbine chambered in an obscure wildcat.