Montana Rifle Company

Same Name, New Rifle

feature By: Terry Wieland | July, 25

The report on those can be found in Rifle no. 300 (September, 2018), but I’ll summarize as follows: The actions, based on the pre-’64 Model 70, were so buttery smooth that you could work the bolts with your fingertips without moving the rifle from your shoulder (invaluable for follow-up shots, should they be needed) and the accuracy of both was so assured and consistent it became boring.

Since then, much has changed. Montana Rifles, then situated in Kalispell, Montana, ceased operation, was briefly resurrected with new investors, and then ceased operation again. Finally, the name came to rest as part of Grace Engineering Company, a large industrial operation in Michigan that produces everything from archery equipment to medical devices. The common denominator is a requirement for precision work with specialized alloys.

The original Montana Rifle Company produced its Model 70-clone action (with a few improvements) using investment casting. As well as, it button-rifling its own barrels, and a large part of its business was producing barrels for other rifle makers.

There is no question about their accuracy, as my above-mentioned experience illustrates.

When Grace purchased the name, existing stock and machinery, it moved the rifling machines to its plant in Memphis, Michigan, where it continues to produce Montana’s famous barrels. Grace was not happy with investment casting, however, and its new actions are machined from billets of 416 stainless steel. It has also made a couple of modifications to the action itself, including allowing push-feed of the first cartridge into the chamber. This has long been a common custom modification on Mauser 98 and 98-clone actions as well as pre-’64 Model 70s.

Grace also inherited Montana’s old accuracy guarantee, which was, on some accuracy models, a half-inch at 100 yards. In various places, I’ve suggested that such guarantees are lunacy (or at least inadvisable) in that there are too many elements beyond the gunmaker’s control. It’s simply a recipe for headaches. Grace’s website still states a ½ MOA guaranteed for its Junction model but not for its lighter Highline. This may be an oversight, since I’m advised the company plans to revise this to one inch at 100 yards, with the usual caveats about quality ammunition and proper shooting conditions.

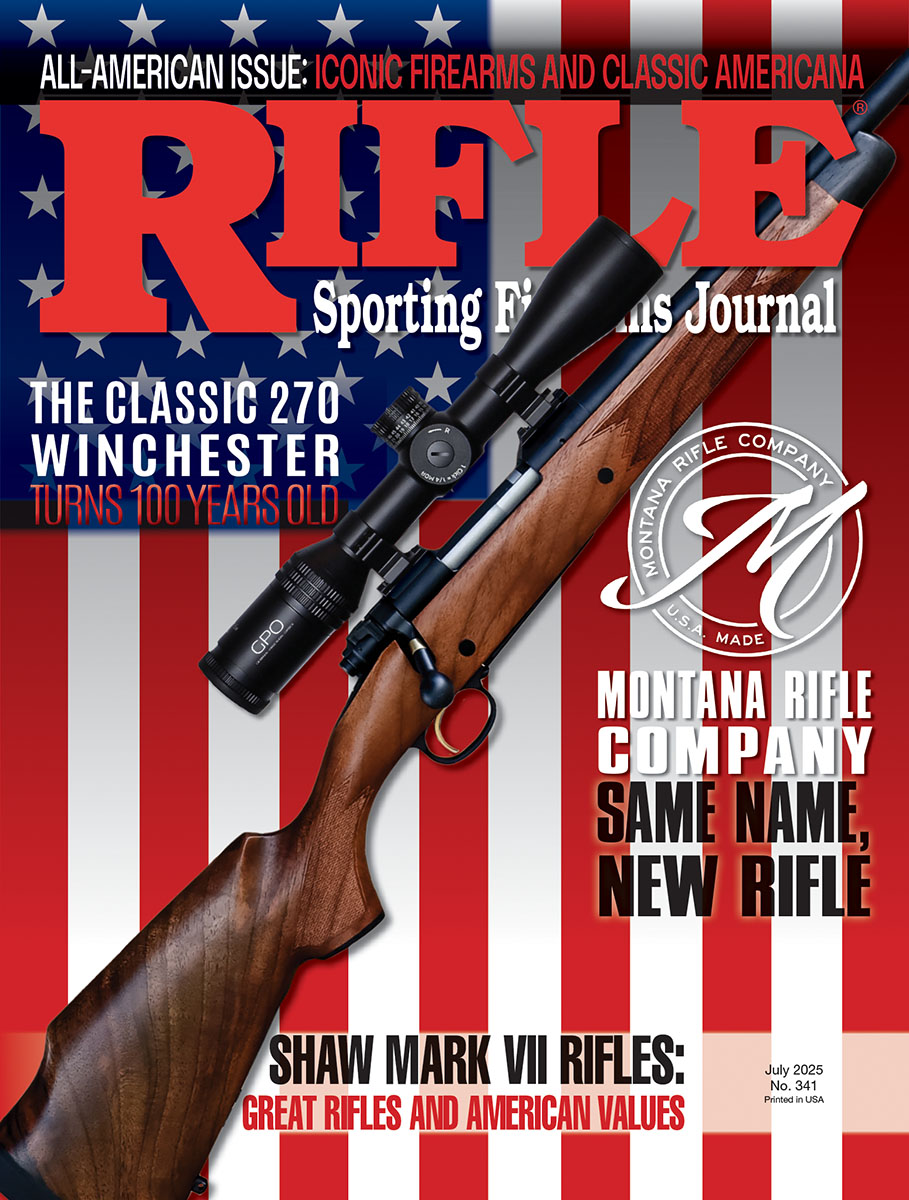

The rifle I received for testing is the Junction, in 6.5 Creedmoor. Unlike the late-lamented SCR-SS and MTR I tested in 2018, this is a more conventional hunting rifle, with elegant lines and a very nice walnut stock in almost, but not quite, American Classic styling. I am advised that Grace has a deal with Benelli to produce its walnut stocks, and one of its first moves was to upgrade the walnut used for standard rifles. If mine is typical, no one should have any cause to complain about the wood.

The original Montana action was designated the MRC 1999; Grace’s redesign is the Model 2022.

Another modification to the action includes integral scope-mount bases of the Picatinny-rail variety, not as a single rail across the top of the action, but separate bases front and back with three notches in each. This approach has both advantages and disadvantages.

On the plus side, there are a plethora of rings and mounts available in Picatinny configuration; the major disadvantage is that you can only use Picatinny rings. While there are dozens available, almost all have that angular military/industrial appearance that may look all right on military-style rifles but is downright ugly on a rifle intended to exude classic elegance.

A second disadvantage is that it limits your options when it comes to scopes and how you can position the scope on the rifle. Most of the one-piece Picatinny mounts are considerably higher than I like on a hunting rifle.

When I received the rifle, I figured it would be a good opportunity to try the new line of compact riflescopes from GPO (German Precision Optics). GPO optics are very high quality, and the new Centuri models have 30mm tubes, illuminated reticles, parallax adjustment, eyepiece focusing and reticle adjustment turrets that allow conventional adjustments or zero-lock settings for long-range targeting.

The one I received first was the Centuri 4-16x44i C, a super-compact little gem of a scope that would have fit in beautifully with the traditional appearance of the rifle, being neither huge nor heavy, and without a bulbous objective bell that requires a very high mount. Alas, the scope’s tube is only 4.3 inches from bell to bell. Some one-piece ring-and-mount units I have would have fit the tube but been too short to reach the bases on the action, while individual rings fit the action but were too far apart for the short tube.

Mike Jensen, co-founder of GPO and its American CEO, told me there is no mount combination on the market that allows that scope to go on that rifle. Back to the drawing board.

I’m advised that Grace is working on a variation of the action that will omit the Picatinny bases and allow conventional scope mounts. My own preference, given the aesthetics of the Junction, would be a set of the sleek S&K mounts or the classic Leupold. In fact, Leupold mounts using extended rings would have allowed me to use the Centuri compact scope I wanted originally.

As you can see from the photos, however, the current arrangement both works well and looks good, and the GPO scope itself is first-rate.

The Centuri models have a custom elevation turret from Kenton Industries, and have no downward elevation adjustment as they come from the box. To free the turret in order to give yourself some leeway requires, reading the accompanying instruction brochure first very carefully, then dismantling the turret using the special tool that accompanies the scope and then moving the locking ring.

Frankly? Dinosaur that I am, I like being able to mount a scope, bore-sight it and head for the range without having to decipher instructions. Still, I also realize that with highly technical mechanisms such as the Kenton turret, there is no way around it. Once I had it figured out, I found it to be extremely easy to adjust, set and reset. Oldish dog, newish tricks.

As a general observation, the Kenton turret was both easy to use and not so large as to be awkward or in the way on what is an unapologetic hunting rifle.

Now, back to the Montana Junction itself.

One of the things I admired about the old Montana Rifle Company was its ability to combine accuracy and flawless functioning with style and aesthetics. There were a few missteps, of course. The old ASR’s walnut stock was spoiled by the addition of a finger groove on the forend, combined with a narrow and utterly useless patch of checkering that was reminiscent of the stock on the ancient P-17 Enfield, as “sporterized.”

Of course, the same can be said of the revered pre-’64 Model 70, whose bolt-release can most charitably be described as chintzy.

As if I needed anything else to make me feel old, reading Grace’s explanation on its website of the controlled-round versus push-feed mechanism brought home with a jolt the fact that many younger shooters may never have heard of, much less seen, an action that feeds a round out of the magazine and into the chamber – held snugly all the while by a substantial extractor, rather than popping loose and rattling all over as it’s fumbled in.

Similarly, many may have no familiarity with a three-position wing safety whose middle position allows the bolt to be worked while on “safe,” and whose rear position not only clamps the striker but also locks the bolt closed. All of these functions are, to me, essential for any top-notch hunting rifle that may be carried in a saddle scabbard, or up a mountain slung on your shoulder while you use both hands to climb.

The common features of many newer rifles – a safety that only blocks the trigger rather than locking the striker, and provides no way to lock the bolt closed – are simply not good on a hunting rifle that will be carried in rough conditions.

Other features found on the Junction include a rail on the underside of the forend, for attaching a bipod and a detachable muzzle brake. Its 25-inch barrel (with brake) has a 1:8-inch twist in 6.5 Creedmoor. The trigger is the basic and excellent Model 70 configuration. As the rifle emerged from its box, the trigger pull was, as advertised, a crisp 3.5 pounds, but it can be adjusted down to 2.0 pounds. Its five-round magazine is the standard Model 70 box with a hinged floorplate.

The rifle proved very pleasant to shoot off the bench. Its weight (9 pounds, 10 ounces, with scope) combined with the brake meant that its recoil was negligible. I tried three types of ammunition: Hornady 140-grain ELD, Match 147-grain ELD and a generic handload I put together two years ago using Berger 144-grain VLD Long Range bullets.

The company guarantee is for three shots. In all three cases, my groups measured a little more than an inch, and try as I might, I could not get them any tighter. I have no doubt that if I devoted some time to load development, I could come up with something that would outperform that, but the purpose here was to test the rifle with factory match ammunition as called for by the guarantee. I tried my handload simply because it has proven to be very accurate in other 6.5 Creedmoor rifles.

If I had to offer an explanation for the groups I got, I would attribute them to an arthritic shoulder and my fading skills at benchrest rather than the rifle itself. I don’t think Montana Rifles has anything to prove when it comes to accuracy.

At the moment, the Junction is available in five calibers: 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5 PRC, 7mm PRC, 308 Winchester and 300 Winchester Magnum, although rumor has it that Grace intends to expand that to 11 different cartridges, probably up to 375 H&H.

The new Montana models from Grace Engineering – the Junction and the lighter, composite-stocked Highline – list at $2,595, which is a mid-range price for a premium hunting rifle these days.

As the line expands, I hope it will include the SCR-SS and MTR rifles. They were superb.

As for the Junction, my overall impression is that true to its name, it’s a junction that combines modern features (muzzle brake, bipod accommodation, Picatinny mounts) with old-fashioned virtues such as controlled-round feed and a three-position safety. Such hybrids do not often work out. The Montana Junction is one that does.