Light Gunsmithing

Iver Johnson Model X

column By: Gil Sengel | September, 25

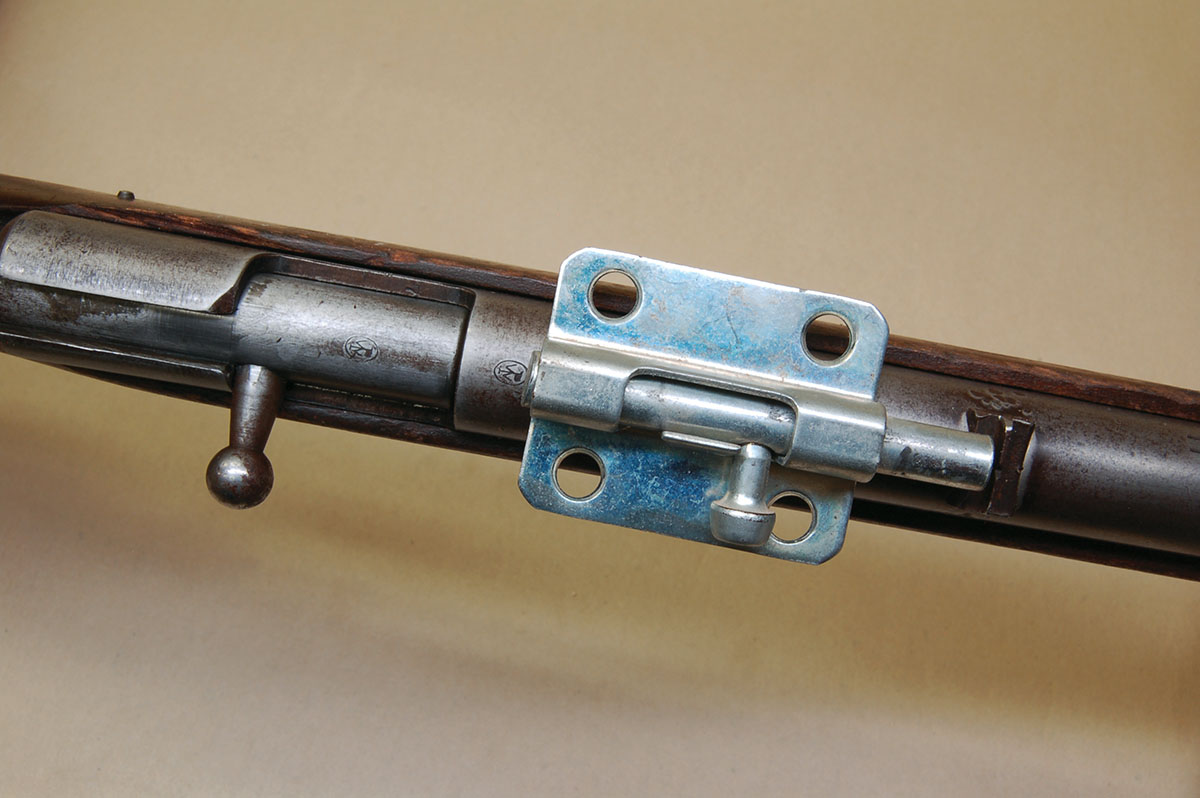

Like other well-known firearms designers of his era, Browning’s interest lay with repeating arms, whether handguns, rifles, shotguns or machine guns. There was, however, one exception. Browning designed the Winchester M1900, single-shot 22 rimfire. The receiver was nothing more than a bolt-activated door latch, hardly a new concept, as Mauser had been making rifles on the same idea since at least 1872. Plus, the M1900 design was not complete – it did not have a rebounding firing pin or safety! Thomas C. Johnson of Winchester had to correct this and other faults – hardly a brilliant design.

Fortunately, this is not the case with the rifle featured here. The design is brilliant, shockingly simple and completely safe when loaded. While the rifle is a bolt-action, single-shot 22 rimfire of the genre “boys rifles,” it could just as well be chambered for 25/20, 32/20 or any of the various sub-22 rimfires available today. It is the Iver Johnson (IJ) Model X. That’s right. Iver Johnson.

Today, there are few shooters who have heard of Iver Johnson’s Arms and Cycle Works. The chronicles tell us the company began in 1871 when Norwegian gunsmith Iver Johnson and Swedish gunsmith Martin Bye began making muzzle-loading pistols in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Also, the IJs’ outward appearances resembled several cheap American and imported guns sold as “house brands” and “hardware store” items. The reputation is unfair as IJ made revolver models that were just as good as S&W or Colt, but were lighter weight due to being chambered for less powerful cartridges: 22 rimfire, 32 rimfire, 32 long centerfire and 38 S&W only.

To dispel any doubt about IJ’s design/engineering capability, consider that in 1893 the company introduced its premier Safety Hammer Automatic Revolver. The safety part referred to IJ’s invention of what is a form of today’s transfer bar safety. It positively prevents the gun from firing unless the trigger is pulled and held to the rear. The word Automatic in the title indicates automatic

Despite the growing popularity of the 22 long rifle, IJ didn’t make a rifle to fire it. In fact, the company didn’t make any rifles at all. World War I came and went, and still no inexpensive 22 rimfire rifle. Then, in 1928, the situation changed with the introduction of the Model X. Iver Johnson’s description of the rifle is shown in a photo from the 1931 Stoeger catalog. The text mentions a “knob forend.” As can be seen from other photos, the knob has been removed from my gun. Apparently, it offended a previous owner’s sensibilities, but the orange paint? Perhaps the fellow was temporarily out of stock finish.

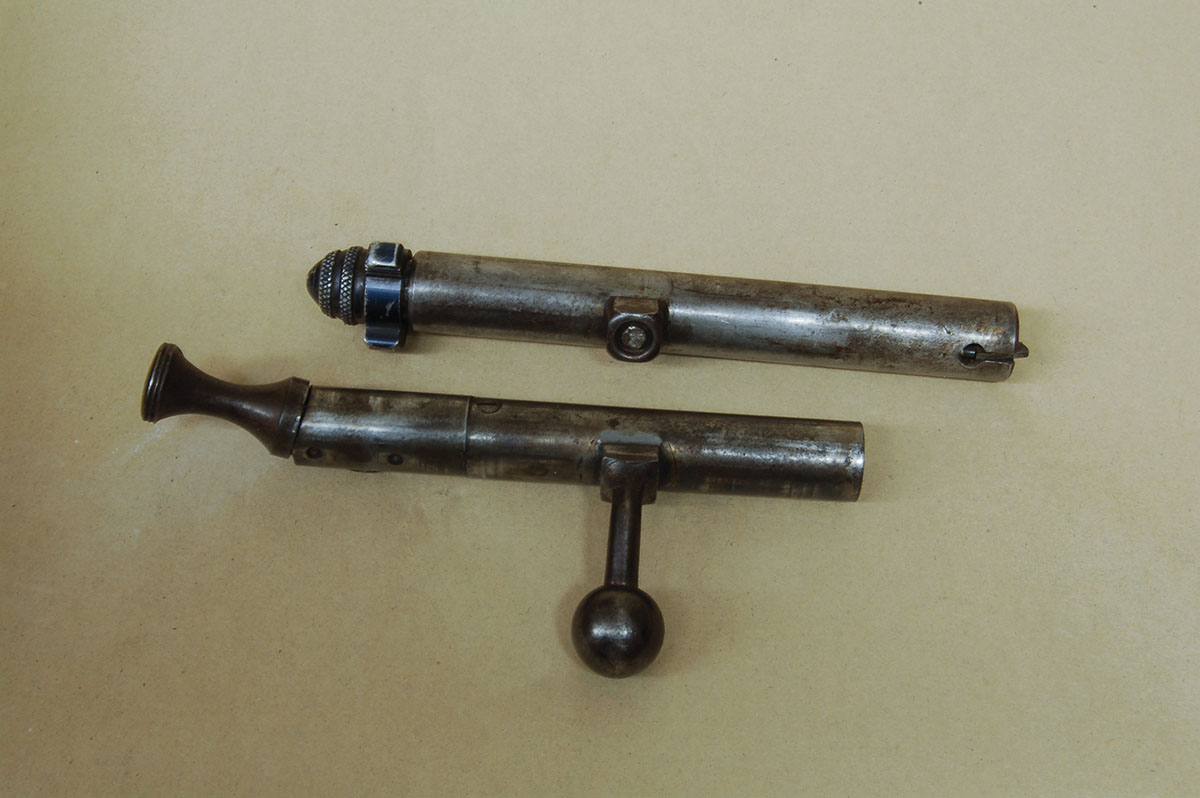

As said a bit earlier, this is not an ordinary single-shot boys’ rifle. The design is brilliant, worthy of a great gun designer, but that’s not what happened. The inventor was a chap named Arthur P. Curtis, who one reference describes as “an assistant to the president” of Iver Johnson Arms and Cycle Works, whatever that means. Mr. Curtis may not have been a John Browning, J.D. Pedersen or William Mason, but he conceived a simple, safe and easy-to-produce single-shot mechanism, something none of the great designers ever did.

The rifle is now cocked, loaded and completely safe due to the safety parts being .16-inch thick case-hardened steel and not the bent sheet metal of the Remington M510 or later Winchester M47.

The automatic safety feature of the last two rifles is often found to be filed away, bent or difficult to engage/disengage due to excessive wear. To disengage the Model X safety, it is tempting to reach up and pull it down with the thumb of the shooting hand just before firing a shot. One pre-World War II reviewer said this very thing. Iver Johnson and Mr. Curtis did not intend this. A small notch was cut in the rear of the action wall for the safety arm to fall into.

Indeed, it had to be this way to prevent the safety from being pushed or by simple handling or carrying in the field. Proper disengagement is to grasp the safety with the thumb and forefinger (it is shaped for this), pull back and push down, then position the hand on the grip and trigger. No accidental discharge is possible; that’s why it’s called the “Safety Rifle.” Another brilliant design feature of the Model X is the long, flat spring on the bottom of the receiver. As shown in the photo, it serves as a return spring for the trigger and sear (both of which are .250 inch thick case-hardened steel) and to control the extractor in its back-and-forth movement. It couldn’t be simpler. This spring is .060 inch thick and could be replaced with a thinner one to lighten the trigger pull. The trigger pull on the rifle shown was just over three pounds, so that was not needed.

The IJ Model X is simply fascinating to anyone interested in rimfire rifle design. Most all of its few parts are made from steel and appear to be case hardened. The only stamped sheet metal is the trigger guard and buttplate. Thus, if not abused, the gun should last almost forever. The only boys’ rifle so constructed.

The chronicles tell us there were three variations of the rifle produced. These included two stock styles, two sight options and 22- and 24-inch barrels (maybe). Designer Arthur Curtis did a good job. A Model X belongs in every serious collection of 22 rimfire boys’ rifles.