The F.I. Combo Pistol/Carbine

A Working Two-Fer At Last

feature By: Art Merrill | September, 25

However, the two-fer-one idea has persisted, most famously in attaching quick-disconnect buttstocks to the Mauser C96 “Broomhandle” and Luger military pistols. Here in the US, the National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA) regulates short barreled rifles (SBRs), those with barrels less than 16 inches in length, and attaching a buttstock to a handgun is considered making it an SBR. However, there are exceptions to the rule, such as the above-mentioned historical curiosities.

Today there are a number of inexpensive conversions kits for the Glock pistol that are essentially complex buttstocks that circumvent NFA regulation on a technicality by designing the buttstock as a supposed arm brace and that is nonetheless shown fired with the “arm brace” braced against the shoulder. These have the same shortcoming as their predecessors in utilizing short-pistol barrels. There is at least one

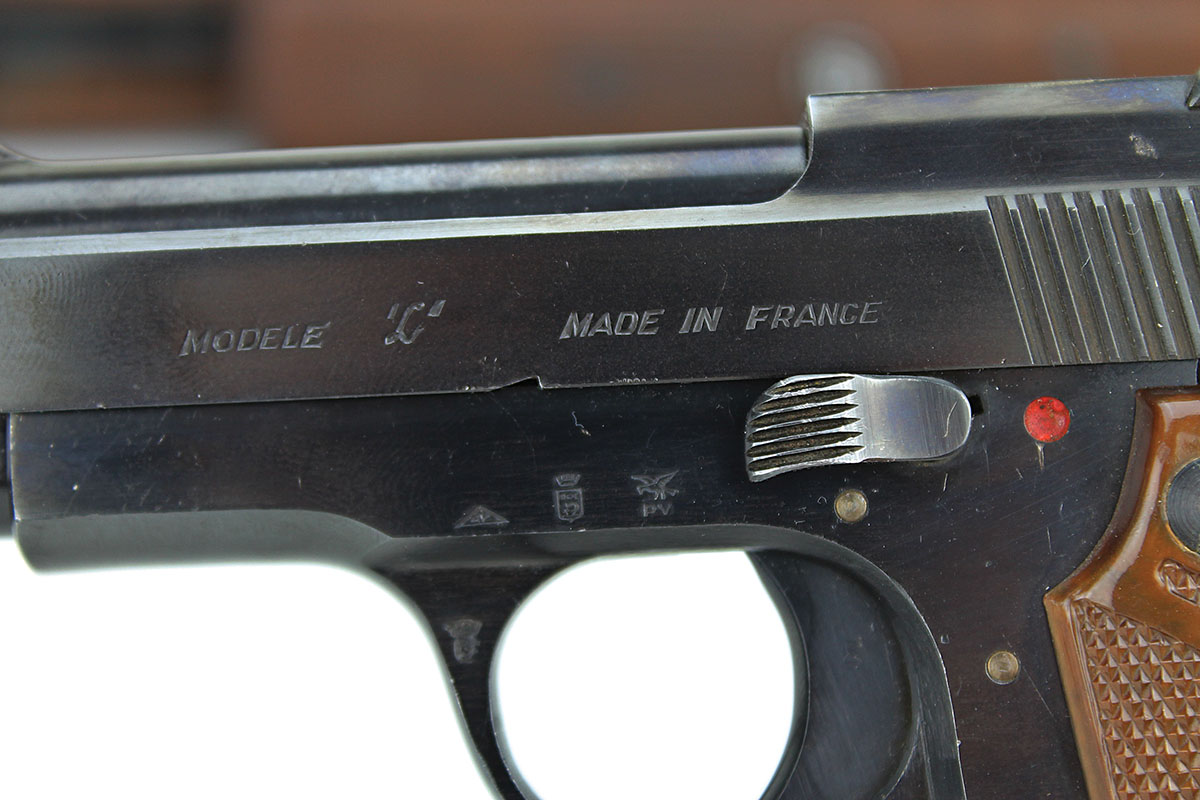

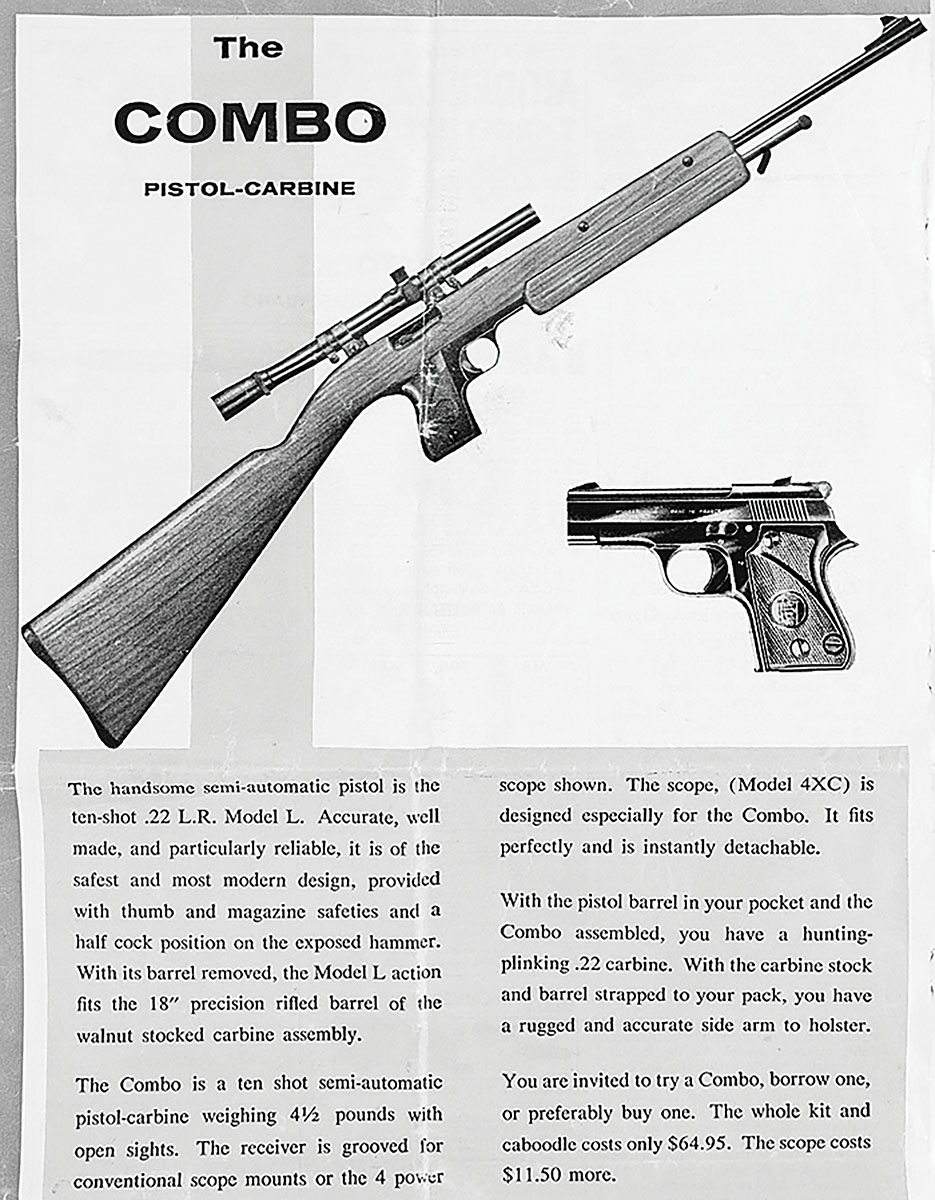

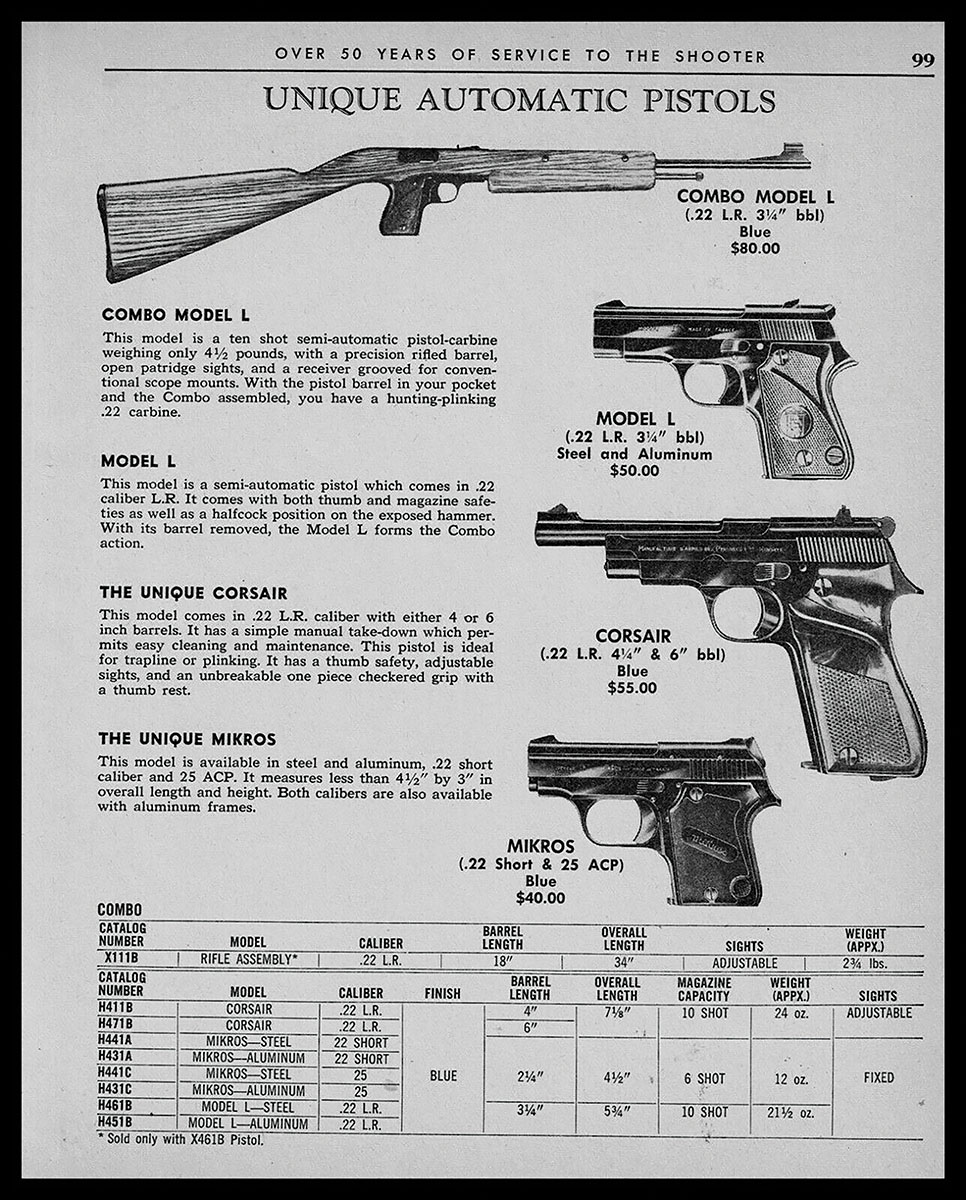

Forgotten now is perhaps the first commercially and practically successful idea in a true pistol-carbine conversion, the FI Combo of the 1960s that mounted the French Unique Model L pistol to an American barrel/stock assembly. This melding of French and American engineering attaches a shoulder stock and lengthens the barrel, and the conversion is indeed achieved within seconds, in the field, without tools. More than that, the conversion produces a full-on carbine from an accurate pistol. Sadly, the FI Combo was legislated out of existence in 1968.

French company Manufacture d’Armes des Pyrenees Francaises manufactured the Unique Model L pistol, but the carbine barrel/stock of the FI Combo was originally a product of the American company Firearms International Corporation (FIC) of Washington, DC (not to be confused with the current Firearms International, Inc. in Texas). France turned out two variants of the FI Combo for the European market called, unsurprisingly, the “Combo” and the “Konvert.”

The 22 Long Rifle FI Combo hit dealer shelves here in 1960, selling for $65 (about $693 in 2025 dollars), but by 1969, it

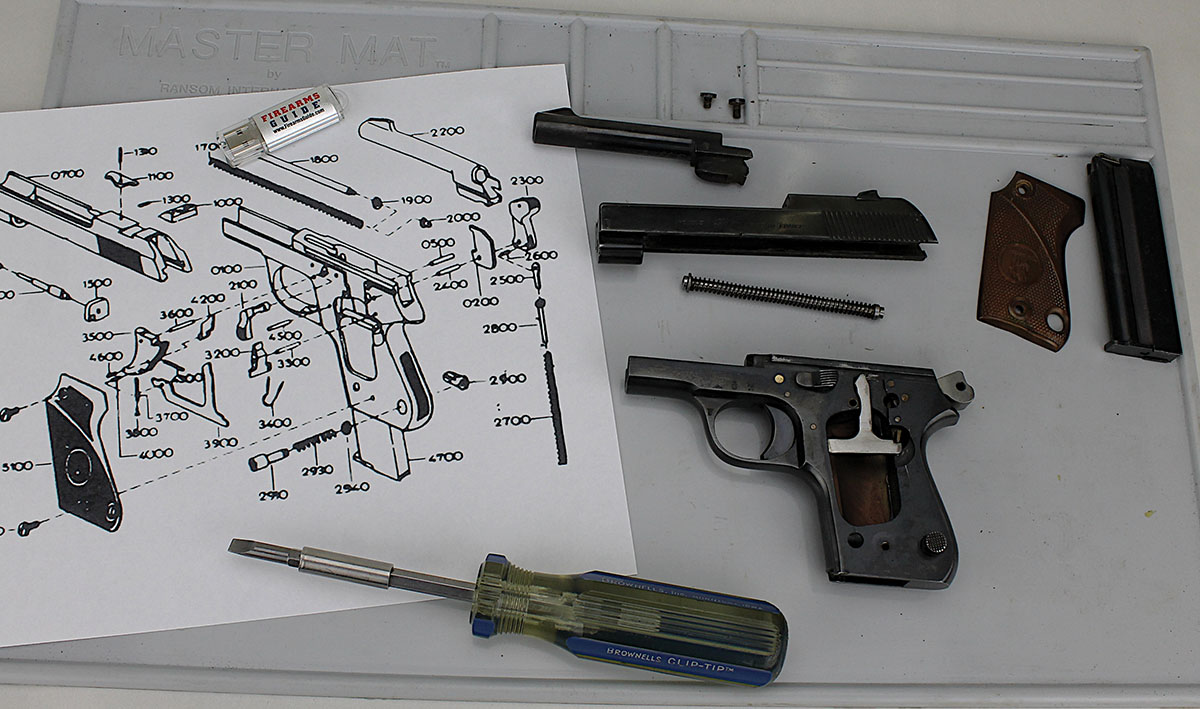

Converting the FI Combo from an evil Saturday night special to an innocuous 22 carbine requires first removing or at least dropping the Unique’s magazine an inch or so out of its locked-in position. Rotate the pistol’s safety lever so that it covers the red dot (on safe), lock the slide back and remove the pistol barrel to the rear. The Unique has an “open slide” like some of the Beretta pistols, as opposed to the “closed” slides of most modern semiautomatics, so barrel removal does not require removing the slide. Ease the now-exposed recoil spring guide rod into the carbine stock’s operating rod tube while tipping the pistol frame upward into the assembly so that the carbine barrel’s tenon properly engages the pistol frame. Pull rearward on the pistol to slide it into place on the barrel tenon and insert the magazine to lock the pistol frame to the barrel/stock assembly.

I probably made that sound more complicated than it actually is, though I’ll admit it took me a few minutes to figure it out. Thus, assembled into a carbine, now what is the owner to do with the pistol barrel so that it isn’t lost? I received this FI Combo assembled, and the owner didn’t know how to remove the pistol from the barrel/stock assembly. After I accomplished that, I thought, “Too bad the pistol barrel is gone, that certainly lessens its value and historical interest.” Later, while examining the FI Combo, I noticed a faint rattling in the buttstock as I handled it. In an epiphanous moment accompanied by a chorus of jubilant eurekas, I discovered that the pistol barrel is cleverly stored in a recess under the buttplate. If you inherited one of these Combos missing the pistol barrel, turn out those two butt-plate screws and take a look.

Wood appears to be straight-grained American walnut. In an unusual reversal of the typical two-piece stock configuration, the FI Combo features a lower handguard rather than an upper handguard. Two Phillips-head screws on the lower handguard affix it to the stock and barrel via two bosses; removing the handguard provides access to the op rod and spring. The plastic buttplate on this FI Combo is broken at one of the screws, but the maker’s logo is still clear and sharp.

A simple stamped steel affair, two screws attach a notched plate to the rear sight base. An ordinary sliding elevator provides a coarse elevation adjustment for the rear sight. Quite unusual in configuration, the front sight is a bead on a post, mounted off-center atop a short vertical cylinder. It adjusts for windage by loosening a set screw at the front of the ramp and rotating the cylinder in either direction. Because the post is offset from the center, rotating it moves the post left or right from the center. Unfortunately, the protective sight hood is missing from this example. On the positive side, someone mounted an adequate period-ish Bushnell 3X-7X Custom .22 scope to the carbine’s tip-off rail.

At the range, the FI Combo was a bit disappointing in the accuracy department, as a somewhat loose fit of the pistol frame to the carbine barrel tenon allowed the pistol frame to rock a few thousandths up and down, which was likely the cause of vertical stringing. A stiff seven-pound trigger pull weight didn’t help, either. At 50 yards from a rest, groups averaged about two inches vertically, but only about three-quarters of an inch horizontally. Without that vertical stringing, groups would likely have been quite good.

The current Blue Book of Gun Values ranks the Unique Model L pistol about on-par with Grandma’s ceramic teapot at $90 in 60 percent condition and $300 for a mint example, but adds $500 value as a FI Combo. Interestingly enough, that’s the same value the Blue Book listed 10 years ago, the amount Combos were actually garnering then, and adjusted for inflation, nearly what they sold for in 1960 in 2025 dollars. In the end, when I finished with this FI Combo, it fetched $800 at a gun show. The FI Combo, then, unlike our similarly priced cellphones that become worthless in five years, holds its original value even six decades later.

Not bad for an idea that took 400 years to mature.