The TC73 carbine is fast handling in heavy chaparral.

The TC73 is case colored, which features a peacock-like iridescence when catching the sun.

The year 1873 was monumental in firearm development. The U.S. Springfield Armory introduced its next-generation trapdoor rifle, chambered in .45-70 caliber. Colt introduced the Single Action Army in .45 Colt, known as the Peacemaker. Winchester upped the ante with their Model 1873 lever-action rifle. Its predecessors, the Henry Rifle and Winchester Model 1866, had bronze-framed receivers and were chambered in the .44 caliber Henry rimfire black powder cartridge, which propelled a 200-grain bullet at a velocity of 1,125 feet per second (fps). The Winchester Model 1873 was an iron-framed rifle chambered in their new rifle cartridge, the .44 Winchester Centerfire (44 WCF). The cartridge propelled a 200-grain bullet with 40 grains of black powder, reaching a velocity of 1,500 fps, and was a powerhouse compared to most other cartridges of the day. In 1878, Colt began offering its iconic single-action revolver in the same caliber. Historians say Colt was loath to provide any advertising for Winchester, so instead of marking the barrel with 44 WCF, it was marked Frontier Six Shooter. This was the beginning of a trend. A person could have a handgun and rifle in the same cartridge, which, in many ways, made perfect sense. As the years passed, Winchester added other cartridges to the lineup, including the 38-40, .32-20 and .22 rimfire. Colt and other manufacturers offered revolvers to match.

The TC73 uses a toggle-link system to operate the bolt and maintain forward thrust of the case head.

The Henry rifle, Winchester Model 66 and Model 1873 featured a toggle-link action, a smooth-operating design that fed cartridges quickly and reliably. The Model ’73, as it came to be known, has a tubular magazine secured under the barrel. Cartridges load into the magazine through the loading gate on the right side of the receiver. The cartridge rests in the carrier until the next cartridge being loaded pushes it into the magazine. As the cartridges are inserted, the magazine

A white bead on the front sight makes target acquisition easy.

spring compresses, maintaining rearward pressure on the line of cartridges. When the lever swings forward, the carrier rises, taking the last cartridge loaded with it, and blocking the magazine opening to prevent another cartridge from exiting. In the same motion, the bolt is driven rearward, cocking the hammer. The cartridge aligns with the chamber as the carrier reaches the top of its stroke. As the lever is swung rearward, the bolt moves forward, pushing the cartridge into the chamber. As the bolt comes fully forward, the carrier drops to allow the next cartridge to slide rearward onto it. In the cocked position, the toggle links align perfectly with the bolt, preventing the bolt from being pushed rearward when fired. Pulling the trigger releases the hammer to fall and strike the primer. The action is simple, smooth and efficient. A sliding dust cover keeps grime out of the action and moves backward as the rifle is cocked.

Like all Winchester models in the late 1800s, the options for ordering a Model 1873 were unlimited. Fancy walnut stocks, engraving, gold inlay and special sights could all be had for the right money. The rifle came in round or octagon barrels and various barrel lengths ranging from carbine (20-inch), rifle (24-inch) and musket (30-inch). Stocks came in straight to sporting pistol grip and featured the classic crescent or curved carbine style butt plate. One oddity that frustrates collectors now is that the serial number was stamped on the tang rather than on the receiver. This means the rifles serial number could have been swapped at any point in its history if repairs made it necessary to do so.

Cocking the lever starts the reward motion of the bolt.

At the end of the lever stroke the hammer is cocked and a new cartridge is inline with the chamber.

In the never-ending quest for powerful, flat-shooting cartridges, Winchester turned to John Moses Browning’s stronger vertical locking lug designs for the Model 1886, the Model 1892, the Model 1894 and, finally, the Model 1895. The Model 1873 became obsolete, and production ceased in 1919, with over 700,000 units manufactured.

The obituary for the Model 1873 was yellowed and torn until 60 years later, when Baby Boomers decided to live out their childhood fantasies by dressing up as cowboys, cowgirls, gunslingers, saloon girls and cavalry troopers and compete in cowboy action shooting (CAS). The style of the ’73 made it appealing to those seeking authenticity, and it was quickly discovered that the geometry of the action could be adjusted to shorten the lever stroke and shave seconds off completion times. In a matter of years, the familiar shape of the Model 73 was seen at CAS events worldwide. The slap in the face was that none of the reproductions, even those trademarked “Winchester”, were made in the USA. Most are imported from Italy, with the remainder coming from Japan. Thanks to Taylor’s & Company, that just changed. After a century, an upgraded ’73 is again being made in the USA!

The muzzle is threaded for a suppressor.

The new offering, made by Taylors & Company, is aptly named the TC73. Unlike the current crop of new lever-guns, the TC73 retains its traditional roots with a classic American walnut stock, color-cased receiver, blued barrel and tube magazine. Of all places, it’s produced in Winchester, Virginia. While Wyatt Earp would instantly recognize the TC73, it departs from tradition in two ways. First, the barrel is threaded for a suppressor, a common feature nowadays. Second, it is chambered in the economical 9mm Luger (9x19mm, 9mm Parabellum).

The original Model 1873 was chambered in the black powder .44 Winchester Center Fire, also known as the .44-40. The TC73 is chambered in the much more compact 9mm.

The TC73 excites me in many ways. First, I’m a red-blooded American; any time something is manufactured in the USA, I know it means quality. Bob Hope used to say that “Made in the USA matters”. Second, the history of the Model 1873 is deeply ingrained in our American West, and riding around the vast expanses of Arizona with an American-made carbine feels natural. It can handle self-defense jobs handily, whether the varmints are four-legged or two-legged. Third, I compete in cowboy action shooting and can go through hundreds of rounds every month. The 9mm is cheap to feed. It takes less powder and lead, and brass is free to pick up at most ranges.

While many of the Winchester reproductions are chambered in the traditional Winchester Model 1873 cartridges, most are chambered in standard pistol cartridges, such as the .38/.357 or .45 Colt. For decades, these straight wall cartridges made sense for ease of reloading, the availability of new reloading components and factory ammunition. However, as police departments have transitioned to semiautomatic pistols and away from .38 Special or .357 Magnum revolvers, inexpensive or free brass cases have vanished. At the same time, the cost of 9mm Luger ammunition has dropped, and the brass cases are so common that it’s rare for anyone to bother picking them up. This means brass hounds like me can find all the free 9mm brass we care to bring home.

Like its ancestors, the TC73 has a lever lock that prevents lever operation when in place.

With a ten-shot capacity, the 9mm TC73 makes sense in many ways. For the homesteader, it is an excellent round for protecting farm animals from varmints and feral dogs. The ammunition is inexpensive and readily available, with a variety of bullet types to choose from. The addition of a suppressor makes varmint control discreet. Add a single-action revolver in 9mm, and the homesteader has the perfect packing pair around the farm.

A soft buttpad eliminates any felt recoil.

The TC73 in 9mm is low-recoil fun to plink. Youth shooters can enjoy an afternoon of fast target shooting and learn good shooting techniques, especially when the rifle is equipped with a suppressor. The original Model ’73 was the first Winchester rifle to feature a lever safety that prevented out-of-battery discharges. Competitive shooters appreciate this feature even today. Unloading the rifle is accomplished by carefully working the cartridges through the gun by working the lever or pushing the loading gate down, allowing the cartridges to back out as they were inserted.

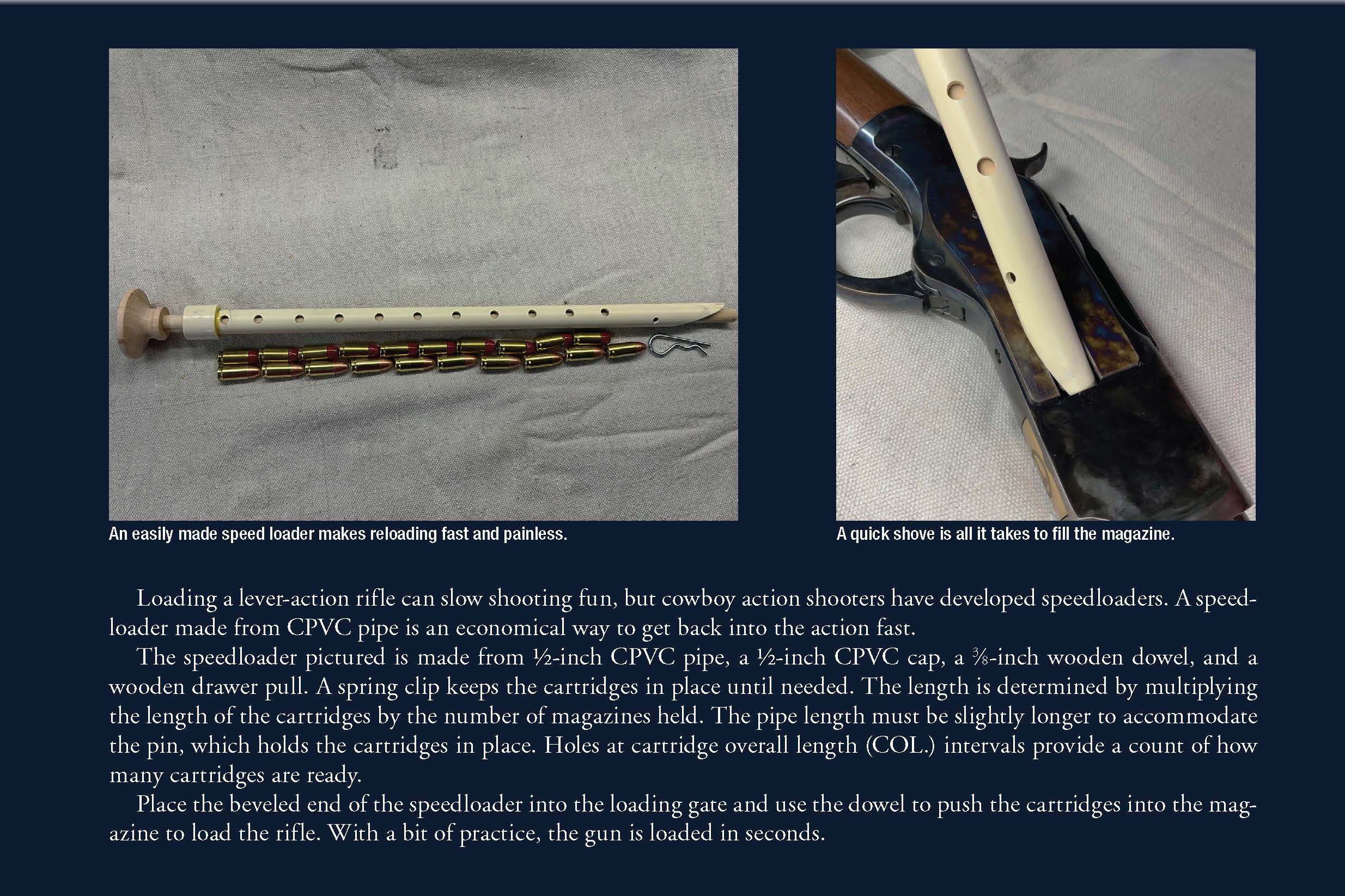

For those who enjoy playing cowboy in friendly competition, the TC73 was recently approved for use in Single Action Shooting Society (SASS) cowboy action shooting matches, provided the muzzle threads are covered with a smooth thread protector. (SASS/CAS ammunition must have a lead, non-jacketed bullet.) For this reason, I chose to cast up enough lead bullets to put the TC73 through its paces.

The Lyman 2660242 throws a roundnose, 124-grain bullet.

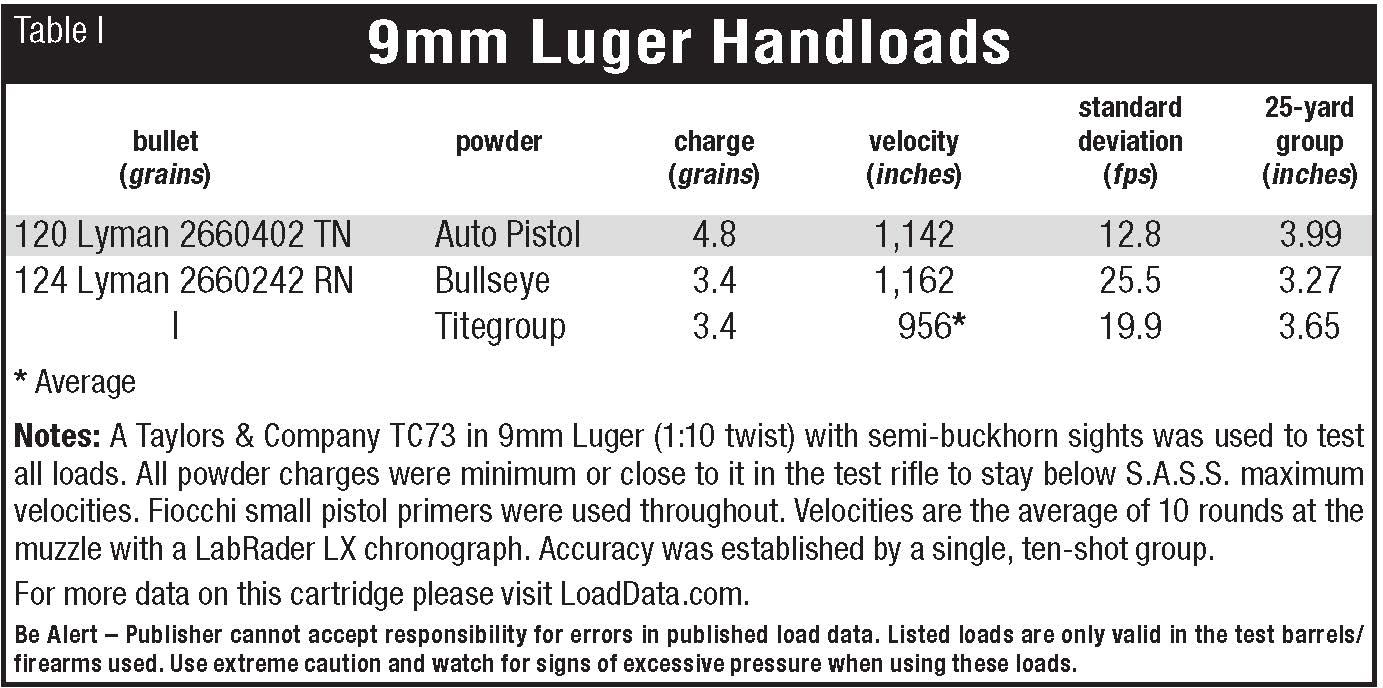

Reloading for any leveraction can be tricky. If the cartridge is too short, the next cartridge in line catches the carrier and jams the rifle. If the cartridge is too long, it won’t entirely fit on the carrier and again causes a jam. Overall cartridge length is critical for proper feeding. Sharply pointed bullets are not recommended for tube-fed rifles. Both Lyman moulds I chose are safe for use. Lyman 2660242

As it was 150 years ago, the model is stamped into the upper tang.

throws a roundnose, 124-grain bullet, and Lyman 2660402 throws a truncated 120-grain bullet. Many cowboy shooters preferred the truncated bullet for use in the ’73. Instead of using bullet lube, I prefer to powder coat (PC) my cast bullets to reduce lead exposure and barrel leading.

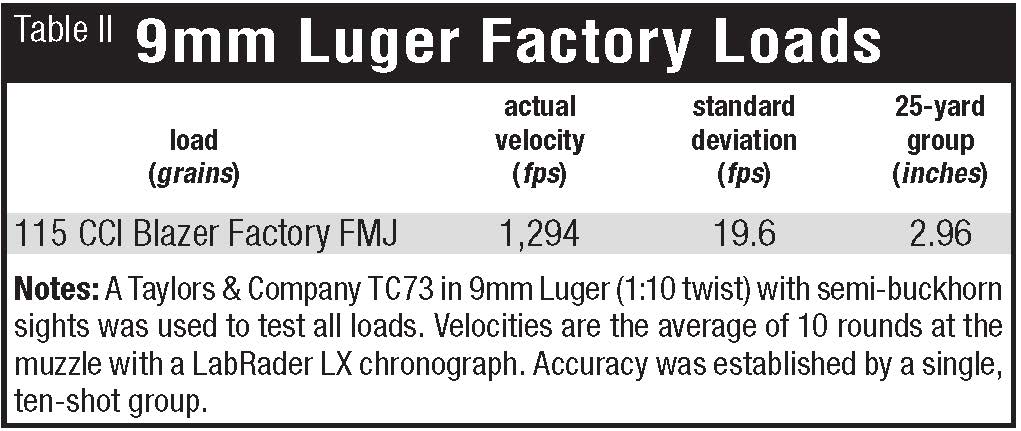

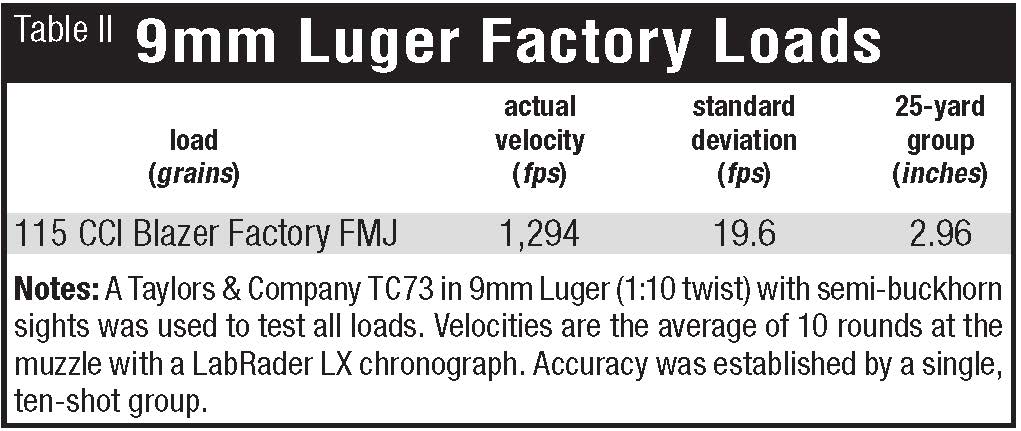

During the testing (okay, playing) of the TC73, I found the rifle accurate and fast-handling. I tried inexpensive CCI Blazer brass cartridges with full-metal-jacket bullets and a small stash of Speer Gold Dot hollowpoint cartridges, as well as Winchester softpoint ammunition. All fed smoothly and shot well. I recommend that homesteaders keep hollowpoint or softpoint ammunition handy for varmints, as full-metal-jacket bullets often pass through a varmint without putting it down, allowing it to return and do more harm to a flock of chickens. Most ammunition is safe for the TC73, except for the G9 Woodsman self-protection round. The pointed tip of the G9 9mm resting against the primer of the round in front of it could cause a round to detonate in the magazine tube.

The dust cover is manually pushed forward and automatically moves back when the lever is thrown to allow case ejection.

I found the TC73 fed all ammunition reliably, including my cast reloads. Recoil was light. With very little practice, the shooter can hold the rifle to their shoulder with one hand on the forearm and run the lever and trigger with the other. Despite what you see on the silver screen, the gun never leaves the shoulder until the shooting is done or the rifle is empty. With a brass punch and hammer, the white-tipped front sight is windage adjustable. The traditional rear buckhorn sights are adjustable for elevation. Like many traditional lever actions, the TC73 has no provisions for a scope mount, nor should there be, as the 9mm has limited range, and a red dot or scope would be distracting on its classic western profile. However, a gunsmith could easily add a traditional tang-mounted peep sight by Lyman. (Drilling and tapping the tang is required.)

Adjustable buckhorn sights can increase the elevation for longer shots.

I have shot a ’73 in competition for almost a decade, which means thousands of rounds down range, and a great deal of fouling. Luckily, the rifle is easy to disassemble and clean. Due to its use in competition, there is a great deal of information on the internet on this topic in case a shooter gets into trouble reassembling the action.

The original Winchester ’73 was favored by anyone needing firepower in a compact but rugged package. The TC73 continues the legacy.

Most cowboy action shooters send their ’73 off to a cowboy gunsmith to have the action smoothed, tuned, trigger lightened and lever stroke shortened to make operation almost effortless and reduce cycle times during a stage. Trust me, seconds matter in a match. Since Taylors is well known in the cowboy action shooter scene, they see what competitors want, and they have built these custom features in the TC73 with their “Taylor Tuned” process. Even if the shooter never competes, they will appreciate the buttery-smooth action.

The TC73 has a shorter stroke than a regular Winchester rifle, shortening competition stage times.

While I am thrilled with the TC73, I’m also excited by what may be coming next. Taylors is tight-lipped but my wish list includes versions in 10mm and 45 ACP with 18-inch octagon barrels and traditional steel crescent butt plates, or maybe a light, saddle-ring carbine model. I can’t help but wonder if Oliver Winchester isn’t looking down, thrilled to see the ’73 brought home again, asking, “What took you so long?”

The 20-shot group at 25 yards shows how well open sights can perform.