Ballard Fever

Variations on a Theme of Grant and de Haas

feature By: Terry Wieland | January, 26

In 1901, C.W. Rowland of Boulder, Colorado, fired the most famous benchrest group in history: ten shots, 200 yards, .721 inches. It was a new record and stood for three-quarters of a century, only being broken, according to most reports, in 1978.

Rowland’s rifle was built by Harry Pope, installing a Pope barrel on a Ballard action. Everything about the rifle was custom or at least, non-factory, from its actual bore diameter (.330) to the manner in which it was loaded (muzzle-breech), but that’s not important. What is important is the choice of action. Harry M. Pope, stickler extraordinaire, used the most accurate action he could find, and that was the Ballard.

At the time, he could have used any number of others. The Winchester High Wall was available, as were the Maynard, Sharps, Martini and Remington Rolling Block. All had their admirers, and all had done great things on shooting ranges, but none could match the Ballard.

In 1947, James J. Grant published the first of his five books on single-shot rifles. Grant was a lifelong collector and connoisseur of single-shots, and he loved them all. But the Ballard is, he wrote, “the most famous and beloved” of all the old single-shot rifles.

“This was the action most favored and sought after by gunsmiths and riflemen alike for a fine custom Schützen rifle.”

One such gunsmith was Frank de Haas, who in 1969 published Single-Shot Rifles and Actions. The book was edited by John T. Amber, the legendary editor of Gun Digest and himself a great lover of fine single-shots.

“No other American single-shot action gained the wide acclaim and acceptance among target shooters as did the Marlin Ballard,” said de Haas. “It was the ‘action of actions’ for the precision target shooter.”

Grant and de Haas approached the question from different angles. One was a collector, the other a gunsmith. Both were serious shooters, and both adored the Ballard. In light of this and having read the works of both men for many years, it’s odd that I never owned a Ballard, or even really wanted to, until very recently. When it came to single-shots, I was in the Stevens camp first, later the Martini and the Winchester Low Wall. It was not so much that I did not want a Ballard as that I could not afford one, not, at least, one of the fine ones in a caliber I could take out and shoot.

At this point, some clarification is in order.

The original Ballard action was designed by Charles H. Ballard, a machinist, and patented in 1861. It was manufactured in various forms by several different companies, and these are referred to as the “early Ballards.” In 1874 or thereabouts, the patent rights were acquired by Schoverling & Daly, the New York retailer, and they approached John Mahlon Marlin to produce rifles.

At the time, J.M. Marlin had just started out in the gun business, making pistols. He undertook to make the Ballard, implemented some redesigns and improvements, and the first rifles saw the light of day in 1875. Marlin produced the Ballard for the next 15 years, and it’s these “Marlin Ballards” that are the object of all the acclaim.

Although he is not usually mentioned in the same breath as Samuel Colt and Oliver Winchester, Marlin deserves more credit than he is accorded. His Ballards were beautiful examples of production gunmaking, using the finest materials then available, and made to exacting standards.

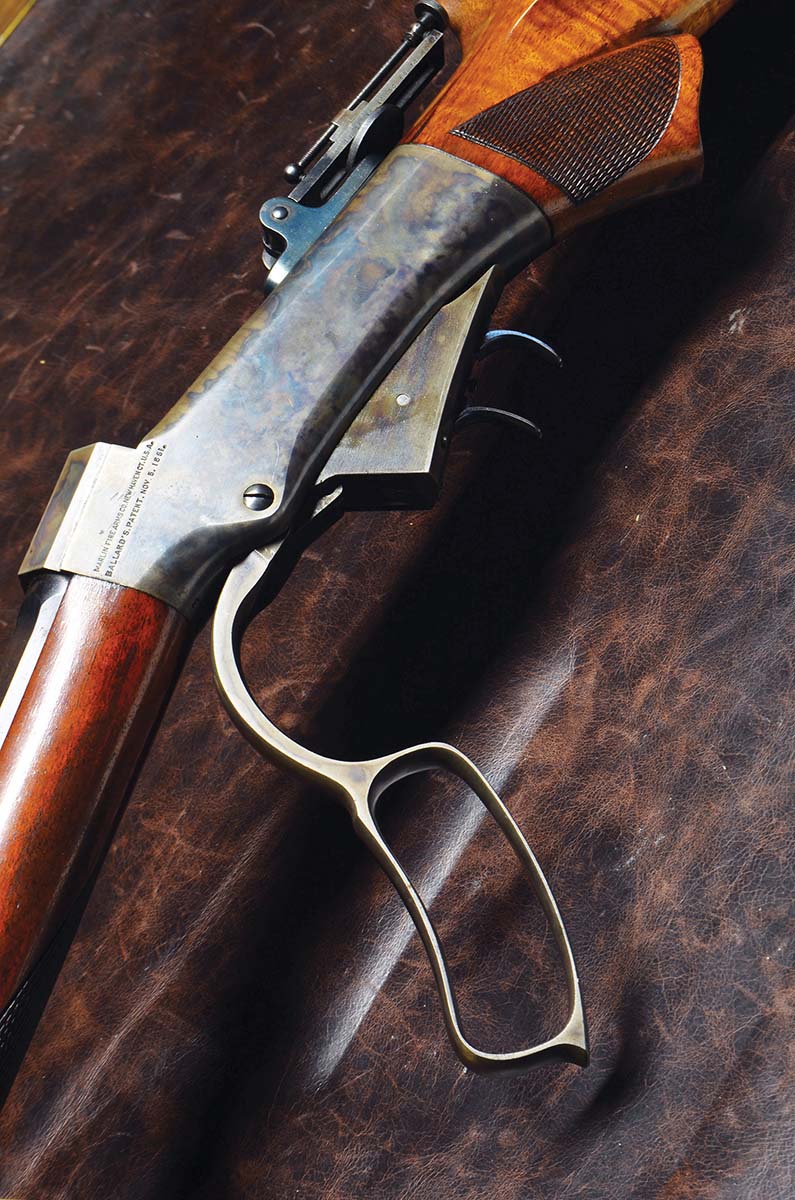

The action can best be described as a falling block that pulls back slightly to the rear, operated by an underlever. The hammer, main spring and trigger mechanism are located inside the breechblock itself. Originally, the breechblock was a hollow casting; later, it was constructed in two pieces. It locks up firmly with the rear of the breechblock sliding up into contact with a slanted shoulder on the frame.

Between 1875 and 1890 (the exact date production ended is unclear), the Ballard was made in myriad forms, some for targets, some for small or big game. It was chambered in everything from .22 rimfires up to big .450s, all using black powder. As every authority points out, it is not the strongest action. The two-piece breechblock can open up “like a book,” according to James Grant, and should not be used as the basis for any modern high-pressure cartridge. Most authorities draw the line at the 22 Hornet, and even that’s questionable.

What is it suitable for? Well, Ballard itself (or rather, Marlin) developed two of the most famous target cartridges of the nineteenth century, the 38-55 and the 32-40, and these are obviously good, either the original black powder or the low-pressure smokeless handloads.

The most popular use for Ballard actions in the barbaric 1920s and ’30s, when many fine single shots were stripped for their actions, was 22 rimfire target rifles. This is fine with a shot-out relic with no collector or historic value, not so fine with a rifle in otherwise excellent condition that could be shooting again with a little care in determining the caliber and making ammunition.

For this reason, it’s rare these days to come across a Ballard in fine, original condition chambered for anything unusual. Most, it seems, have been scavenged and cannibalized.

In 1884, Marlin introduced two Ballard models that became famous and highly prized. These were the Union Hill No. 8 and No. 9. They were unapologetic offhand target rifles, with long, heavy barrels, target-type stocks with appropriate Schützen buttplates, tang rear sights and globe front sights. The No. 8 had double-set triggers, the No. 9 a single trigger to comply with the rules at some clubs. Both were fitted with four-finger loop levers.

According to the books, the Union Hills (named for the famous target range in New Jersey) were offered in only the 32-40 and 38-55 chamberings. In fact, the 32-40 was designed specifically for the Union Hills. This brings us to an unusual Union Hill No. 8 that sold at the Rock Island premier auction in August 2025. If anyone would like to look up lot No. 3096 to see the auction description, visit RockIslandAuction.com.

The rifle is a perfect letter Union Hill No. 8 in every way except one: There are no caliber markings on the barrel, and it is neither 32-40 nor 38-55. Rock Island’s evaluators concluded it might be a 32-20, and listed it as “.32 C.F.” In volume three of James Grant’s series, he wrote that some Union Hills had been chambered for the obscure 32-30 Remington, and I thought this might be one of those.

I took the rifle to single-shot specialist Lee Shaver, who dismantled it, made a chamber cast, and slugged the bore. It turned out to have a 32-20 chamber, but with a .308 bore instead of .313. This surprised Lee, who has barreled a half-dozen rifles in that way over the years, and thought he’d originated the practice. I am semi-reliably informed that Thompson/Center’s 32-20 barrels were arranged this way also, but I can’t confirm it.

While the rifle was apart, Lee examined it carefully and cleaned the innards. His opinion: The rifle had hardly been fired at all in 140 years, and in fact might never have been completely dismantled since it left the factory. The inside of the breechblock had original factory grease hardened to the consistency of black treacle candy. The bore itself is almost pristine: Bright and shiny, with sharp rifling. How it evaded the action scavengers in the ’20s and ’30s, who knows?

Having determined what the rifle would shoot, there remained the question of what it was intended for. It’s clearly a Schützen rifle, but it would not be adequate for the usual 200-yard or 40-rod (220-yard) matches of the 1890s. Delightful as the 32-20 is, it’s a 125-yard cartridge at best. Some rifle clubs did hold matches at shorter ranges, however, and perhaps this was intended for those.

With this chambering and its undersized bore, I decided to stick to black powder and cast bullets, for any number of good reasons. If I want more power or range, I have other rifles.

The accompanying table shows the loads tried and the results. Modern 32-20 brass will hold 20 grains of FFg or FFFg, but, depending on the brand, it fills the case to the brim or a bit beyond. This means it will be slightly compressed with a 100-grain bullet, and more with a 120-grain, to stay within the maximum cartridge length.

The 120-grain loads produced a slight ridge around the primer indentation, suggesting pressures higher than one would like. But since the 32-20 was never intended to shoot 120-grain bullets, we’ll call that a failure.

Having tried several combinations, I backed off to 18 grains of Swiss FFFg, the powder that had produced the best results.

The rifle has an unusual sighting arrangement, at least to modern eyes, combining a Marlin vernier mid-range tang sight with a non-adjustable globe front sight. Elevation is controlled with the rear sight, but windage is changed by moving the front sight back and forth in its dovetail. Lee Shaver told me this was not unusual for target rifles back then, but it’s certainly awkward and inexact. It does suggest, however, that the rifle was intended for shorter ranges, where wind and allowing for windage would not be a factor. I decided to leave the front sight where it is for the time being, rather than trying to fine-tune it.

In shooting, I had difficulty getting a consistent sight picture. Next time out, I used a small black bull and attempted a six o’clock hold to put the sights in the same place every time. This cut the group size in half. Also, in shooting the first groups, I did not clean the bore between shots, the goal being not to find a super-accurate load but to determine what would shoot and what would not.

On a later trip to the range, I shot a five-shot group in which the first four went under an inch; the fifth was a flier, as was the sixth. I passed a wet patch down the bore, and the seventh shot then went into the original group, enlarging it to 1.2 inches. We live and learn.

Frank de Haas considered the Ballard brilliant in its simplicity, employing just 20 separate parts altogether, “remarkable in view of the total excellence of the action.” Among its “superb design and construction features,” he listed the massive frame for strength and stiffness, barrel securely screwed in place, buttstock attached firmly with a through-bolt, simple firing mechanism, excellent trigger, fast lock time, and precise and long-wearing control over headspace.

As well, with the action open, the shooter has unimpeded access for loading, unloading, inspection of the chamber and cleaning from the breech. For an action designed in 1861 and upgraded in 1875, what more could one ask?

Neither de Haas nor Grant mentioned it, but the Ballard is an inordinately graceful rifle, with straight lines and gentle curves all melting into one another and without a line out of place. The eye roves over it with no protuberances to interrupt. Such grace translates into fine balance and ergonomic operation. In the hands, it responds almost intuitively.

It also makes the Ballard as photogenic as Marilyn Monroe (or, for the younger crowd, Sydney Sweeney).

Admittedly, the Ballard has shortcomings, mainly its inability to handle modern, high-pressure cartridges. In spite of this, however, its admirers “will still take a Ballard,” wrote James Grant. “Why? Well, it is a hard thing to explain. In fact, I cannot explain it. The best I can do is advise the unbeliever to get the Ballard fever, and if he gets it, I would venture to say it will be a lifelong malady and one for which he will not seek a cure.”

Whether I have the fever, I dunno, but I do seem to be running a bit of a temperature.

.jpg)