Winchester’s 21 Sharp

Hunting, Plinking, Competition and Plenty of Merit

feature By: Art Merrill | January, 26

Creating a new cartridge by modifying an existing one typically starts with converting the brass case by necking it up or down, and maybe shortening it or changing the taper or shoulder angle. In the 21 Sharp, however, Winchester left the 22 Long Rifle brass case as-is and instead essentially necked the bullet down. With a more modern profile for theoretically improved accuracy and a generally higher velocity, the 21 Sharp joins the 22 Long Rifle to give shooters another option in an affordable rimfire hunting and plinking round. Could competition shooting be just around the corner for the 21 Sharp?

Winchester’s 21 Sharp is a viable idea that should have been introduced 135 years ago with the advent of smokeless powders and higher velocities that prompted the development of jacketed spitzer bullets, all of which combined to quickly render roundnose heel-base bullets as obsolete as the round ball. Dispensing with its heel and roundnose was the logical next step at that time for the 22 Long Rifle, too, but for whatever reasons we wish to speculate upon (perhaps key among them being the cartridge quickly became extremely successful commercially and if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it), it didn’t happen.

There have been several pursuits in ditching the heel by necking down the 22 Long Rifle case, but only long after the 22 Long Rifle’s 1884 development by the Union Metallic Cartridge Company. (As an aside, the J. Stevens Arms & Tool Company is usually credited with introducing the cartridge in 1887, but note that Stevens did not manufacture ammunition; rather, the company approached UMC to develop the cartridge for new firearms Stevens wanted to manufacture.) Just after World War II, High Standard experimented with necking down the 22 Long Rifle to create the .177 Hi-Standard. That went nowhere. Starting back in the early 1970s, W.A. Eichelberger of King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, experimented with necking down the 22

Long Rifle case to accommodate bullets of .10, .12, .14, .17 and .20 caliber, the last being a hollowpoint bullet measuring .204 inch in diameter. It appears Eichelberger’s Small Caliber Shooting Supply business offered the 20 Eichelberger Long Rifle cartridge or components until about 2002, though I may be mistaking that for the 20 Eichelberger Squirrel, a center-fire cartridge, as Mr. Eichelberger experimented with those same small bullets in centerfire cases, too.

Hornady took its own shot at necking the case to create the 17 Mach-2 in 2004; it’s still around, but it’s not exactly staggeringly popular. In 1970, Remington experimented with squeezing a .17 caliber bullet in a .22 caliber sabot and launching it from the 22 Long Rifle case – no necking-down required. Though Remington marketed similarly saboted 30-30 Winchester, 308 Winchester and 30-06 Springfield centerfire cartridges launching .223 caliber bullets under the Accelerator label for about two decades, Remington never offered the .17/.22 caliber rimfire version.

Why all the efforts to replace the .22 rimfire bullet? Roundnose heel base bullets are anachronisms. Except for the family of .22 rimfire cartridges, they are commercially as dead as the Brontosaurus, appearing today only in 19th-century cartridges of interest to a small cadre of handloaders and shooters (myself included) precisely because they are anachronisms and there is Frankenstein-ish amusement in exhuming and reanimating dead cartridges. I intended to quip here that a 22 Long Rifle bullet has a ballistic coefficient (BC) only slightly higher than that of a brick, but I couldn’t find the form factor for a brick to calculate its BC, as, apparently, the ballistic coefficients of bricks are of no interest to the construction industry or to anyone else. Suffice to say that, with BCs in the .110-.170 neighborhood, 22 Long Rifle bullet BCs are on the bottom rungs of the BC ladder.

A second shortcoming is that, being essentially the same outside diameter as its case, the 22 Long Rifle’s lead bullet requires outside lubrication – smearing the exposed bullet surface with greasy or waxy lubricant – because there’s no place else to put the lube. You’ve experienced how that outside lube picks up every stray bit of dirt or pocket lint and makes a mess of your fingers and hands in competition or when plinking mass quantities. Sure, electroplating the bullet can mitigate the need for lube, but such bullets are not suitable for all shooting applications.

Winchester finally eliminated the 22 Long Rifle bullet’s heel by reducing the bullet’s .2255-inch diameter to .2105 inch, thereby making the bullet less in diameter than the case, as with all other modern ammunition, and 21 Sharp’s clad, solid copper and FMJ bullets have no need for lubricant. No longer round-nosed, 21 Sharp bullets have straight shanks that abruptly angle sharply to cone-shaped noses terminating in small, flat meplats.

One would expect the sharper profiles of the different 21 Sharp bullets to handily beat 22 Long Rifle BCs, but Winchester assigns a BC of .087 to the 21 Sharp 25-grain Copper Matrix bullet and a BC of .116 to the 34-grain Super X JHP bullet, with no BCs given for the bullets in Winchester’s other two 21 Sharp loadings. BCs are typically calculated with the bullet starting velocity; it’s possible and perhaps likely that the 21 Sharp BCs begin to outclass 22 Long Rifle BCs the further they fly downrange. Inputting bullet weight, length, BC and starting velocity into Berger Bullets’ online Twist Rate Stability Calculator, along with the 1:12 rifling twist rate (compared to 1:16 for the 22 Long Rifle), showed the Copper Matrix bullet is completely stable in flight.

With a bit of coaxing, a .22 caliber collet in an RCBS press-mounted bullet puller was just able to grasp the 21 Sharp’s .2105-inch bullet shank. The 25-grain Copper Matrix bullet withdrew from the case without argument and showed itself to have a flat base. On a scientific scale, the bullet weighs 25.54 grains, the case 9.95 grains, and the powder charge 2.92 grains. Bullet length is .497 inch. The crimp of the case mouth on the bullet, which at first appears to be a roll crimp but under magnification might be considered an abrupt taper crimp, is tight enough to have left an obvious indentation on the solid copper bullet’s surface.

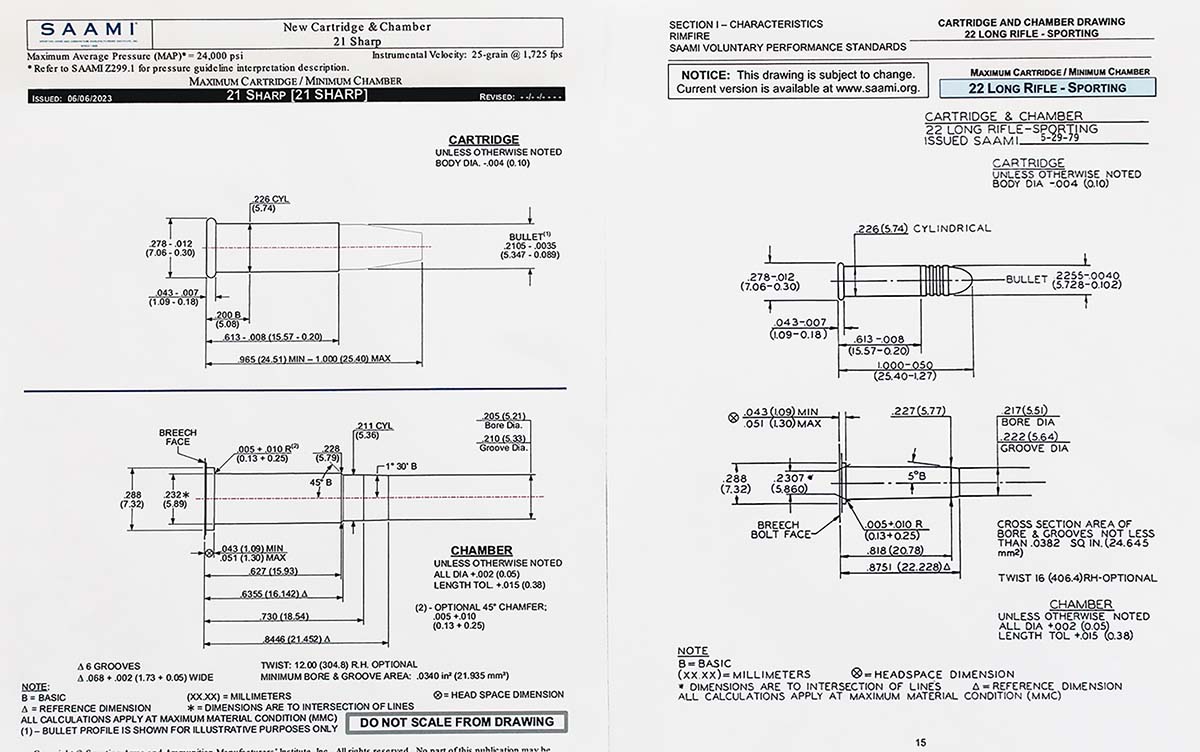

SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute) chamber drawings for the 22 Long Rifle and 21 Sharp show the latter has a shorter and more angular throat. A 22 Long Rifle cartridge will partially enter a 21 Sharp chamber, but the larger round nose of the bullet cannot enter the smaller 21 Sharp throat, so it’s not possible to close the action and fire a 22 Long Rifle cartridge in a 21 Sharp firearm. On the flip side of the coin, the 21 Sharp cartridge will fit and fire in a 22 Long Rifle chamber, but the .2105-inch bullet is under the 22 Long Rifle’s .217-inch bore size. At best, accuracy would be nonexistent, and at worst, the bullet theoretically might yaw sufficiently inside the barrel to become stuck and create a bore obstruction.

Two inexpensive bolt-action rifles chambered for the cartridge are available at this writing: Savage Arms’ MK II FV SR and Winchester’s own Xpert. Both of these rifles have been manufactured as 22s for some time, demonstrating that any box magazine 22 might be made to shoot 21 Sharp with only a barrel change. Noting that changing a Ruger 10/22 barrel is pretty much a DIY affair, I discovered 21 Sharp cartridges feed without any hiccups through all my 10/22s (indeed, Winchester’s 21 Sharp Xpert rifle accepts 10/22 magazines), so we might eventually see barrel makers offering 21 Sharp barrels for the 10/22. However, other magazine rifles may need some extra fitting by the manufacturer; as an example, I found the 21 Sharps flat bullet noses stopped against the breech face when attempting to chamber from a leveraction 22’s tubular magazine.

Shooting the 25-grain Copper Matrix load (the only one available at the time), the Savage MK II FV SR displayed hunting/plinking accuracy on par with any comparably priced 22. Winchester’s Xpert performed better; at 25 yards, the Xpert, in fact, punched nine shots into a single .337-inch hole, landing one flyer outside to make a .527-inch group (the Xpert has a few accuracy tricks up its sleeve that we’ll examine in the future here). That flyer chronographed at 1,760 feet per second (fps), about 80 fps below the other nine running from 1,838 fps up to 1,878 fps and averaging 1,851 fps – a bit more than Winchester’s advertised 1,750 fps for the bullet.

Will the 21 Sharp generate enough interest to be commercially viable, or will we see it go the way of other seemingly reasonable ideas in cartridges that just didn’t make it? I’m sure you can name several. Discussing the introduction of the 21 Sharp with other shooters, a curious, “Why?” invariably arises. The 21 Sharp offers generally higher velocities, yes, but what else? Naysayers – who erroneously seem to assume the 21 Sharp is intended to replace the 22 Long Rifle – point out that the cartridge will require buying a new rifle; if it isn’t commercially successful, the cartridges will disappear, leaving 21 Sharp gun owners with hungry rimfire firearms they can’t feed (can you say, “5mm Remington Magnum?”).

Unfortunately, if shooters at large adopt a wait-and-see attitude, it could generate a self-fulfilling prophecy spelling an undeserved demise of the 21 Sharp, and that would be too bad because the 21 Sharp can stand on its own merits, which include JHP, FMJ, solid copper and copper-clad bullet offerings, higher velocity and inexpensive plinking. The cost of cartridges, about 16 cents apiece for three of the loadings and 24 cents per round for the 25-grain Copper Matrix loading, equates to the cost of mid-priced quality 22 Long Rifle cartridges. Winchester’s new cartridge is the first affordable plinking round to debut since the 22 Long Rifle itself, emphasizing its suitability for plinking. Winchester markets 21 Sharp only in 100-count boxes.

Consider as well that the 21 Sharp’s Copper Matrix bullet, being lead-free, is welcome for hunting where the 22 Long Rifle’s universally lead bullets are prohibited. Not designed to expand, the Copper Matrix bullet instead provides exceptionally deep penetration. Winchester’s 21 Sharp Super X 34-grain JHP bullet has demonstrated rapid and consistent expansion in ballistic gelatin, promising to be an excellent varminter.

Where the 21 Sharp has the potential to really excel is in competition shooting. Here’s a superb opportunity to top the 22 Long Rifle case with a .2105-inch bullet of tangent or hybrid ogive like that found on Berger Bullets’ top-tier competition designs for centerfire cartridge bullets. Beyond potentially outclassing the 22 Long Rifle in standard Smallbore competitions of 50 and 100 yards, such a bullet would leave the 22 Long Rifle bullet gasping in the dust at 400, 600 and further yardage of “extreme long range” rimfire competition today. Perhaps competition shooting may be its real niche that propels the 21 Sharp to wider popularity. However, that will require match-grade ammunition, which isn’t offered, at least not yet, and a match chamber.

It’s a safe bet that the 22 Long Rifle is here to stay and is in no danger of being replaced by any other cartridge, including the 21 Sharp. Ammunition manufacturers world-wide have tremendous capital invested in continuing production of 22 Long Rifle cartridges, which number in the billions annually; there is no less-expensive plinking cartridge, which contributes enormously to its popularity; match grade ammunition is plenty accurate enough at close range to appeal to Smallbore competition shooters; and there must be a kazillion working firearms chambered for the 22 Long Rifle, with perhaps millions of 22s hitting the hunting fields and ranges every weekend around the world.

Winchester’s new rimfire cartridge has a lot going for it, including offering something new and very affordable to evaluate and enjoy, and after some experience with the 21 Sharp, you may pick up on some point that didn’t occur to myself or others. “Better late than never,” they say, and we’re fortunate to be here at the forefront of necking down the 22 Long Rifle bullet, instead of the case, to finally bring the cartridge out of the 19th century.

.jpg)