Light Gunsmithing

Making Simple Tange Sights Part II

column By: Gil Sengel | January, 21

Few of these sights have survived, but they are easy to make. The one started in the last column took a bit of filing, and I ran out of space before it was finished. It will be completed here along with a second sight that is even simpler, requiring less file work.

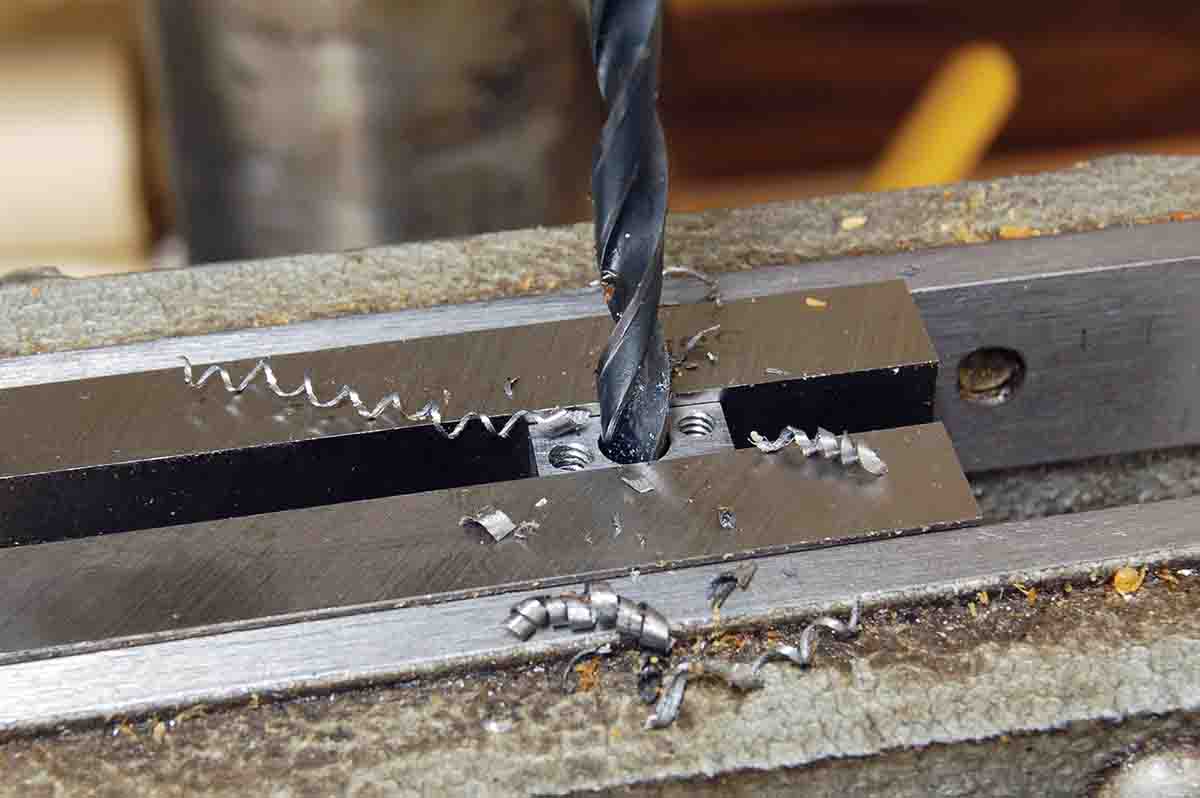

To complete the sight begun last time, it is necessary to drill the aperture in the elevator slide, install a slide locking plate and make a simple spring to hold the staff in position. Drilling for the aperture must be done on a drill press to prevent breakage of the tiny drill bit. First, however, a relief hole must be drilled on the muzzle side of the slide to eliminate “the fuzzy tunnel-vision” effect of looking through the small diameter aperture. A standard 3⁄16-inch bit is fine. This hole is drilled to within about .050 inch of going completely through. It is followed by the smallest drill in a standard fractional set (1⁄16 inch) to form the aperture.

Lastly is a spring holding the staff either vertically or folded down. Springs were made for both sights, but it was decided that fitting and adjusting the small flat springs was just too much bother. Original makers of the cheapest of these sights seldom included springs either, stopping the staff at vertical with a notch or pin in the sight base. Only friction in the hinge joint held it there.

After years of use, resistance would decrease, causing the sight to move, making it worthless for its intended purpose. This was a bit too crude. Instead of a simple machine screw in the hinge joint, I used a special fastener in both this sight and the one made later. It has a large diameter head that was slotted, but the slot was filed away. It was found at a large hardware store, one of those with a section containing hundreds of little drawers filled with countless varieties of fasteners. Some type of plating that wouldn’t blue also had to be removed.

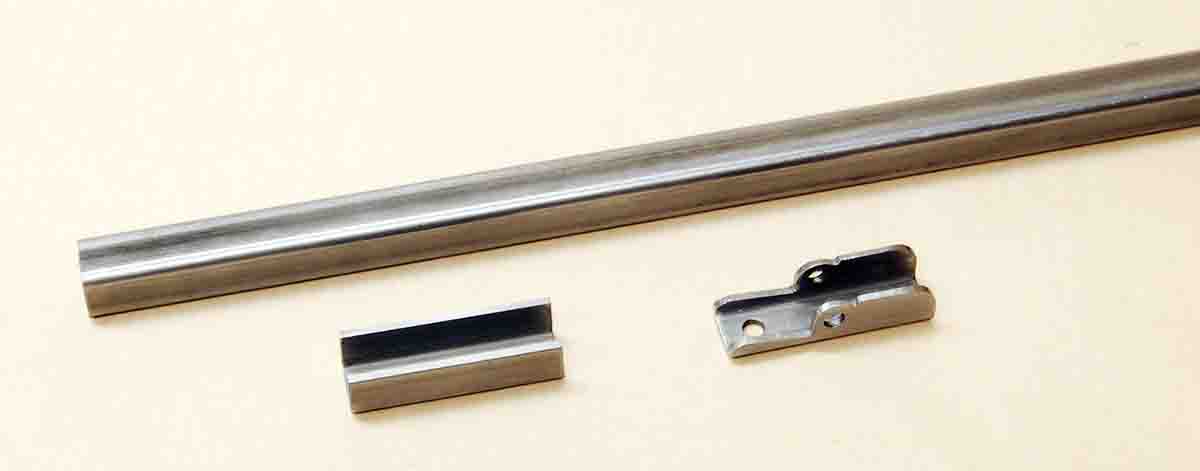

The first part to make is the base, for which is used a piece of half-inch square tubing with one edge cut away. Length depends upon the spacing of the mounting holes in the tang. This tubing is available in 3-foot sections from home improvement stores. The center of the pivot hole for the staff is drilled .200 inch below the top center of the base. Sidewalls of the tubing are a bit thin to tap 6x32 tpi as on the previous sight, so 8x40 tpi was used here.

The staff of the new sight is made from the same ½x¼-inch piece of cold rolled steel used for the first sight; however, almost no filing is necessary this time. After drilling the pivot hole in the staff material, file each side only enough to fit inside the base. Slip in the combination pivot/lock screw. The top edges of the base are now rounded only enough to allow the sight to move forward to sit vertically and fold back far enough to just touch the top of the tang.

Now comes the greatest simplification of this sight over the previous one. Instead of an elevator slider fitting in the sight staff, the aperture is just drilled in a flat piece of metal having a narrow slot cut in the lower center, allowing it to slide on the rear of the staff. Two screws fit the slot and lock the elevation. A photo shows this perfectly.

Few dimensions have been given because they will vary depending upon the particular rifle, height of its open sights, tang height, etc. The elevator on my sight is .070-inch thick sheet metal. Lock screws are standard 8x40 tpi scope mount screws. The slot in the elevator is made by closely drilling holes of screw body diameter (No. 19 drill bit) that are connected by filing using a round needle file.

Now a tip for drilling the tiny aperture (1⁄16-inch) where the large relief hole of the first sight made is not needed: Drill from the rear of the elevator, but first, lightly touch the sheet metal with a new ¼-inch drill. This produces a small depression that will prevent the tiny drill from walking, bending or breaking and ruining the whole day. A photo shows the complete sight on another Hopkins & Allen rimfire.

Of course, making elevation adjustments is by trial and error, just like the originals. Windage is accomplished by shims under the sides of the base, just like the originals (or drift the front sight), but who cares? When properly used as described in the last column, sighting-in need only be done once.

Spending time squirrel hunting or plinking pop cans or targets of opportunity then takes us back to a slower era – a time before the chatter of semiautos was upon the land; a time before money was plentiful; a time before we needed scopes (excuse me, optics) of a power that can discern the gender of a dragonfly at 200 yards. Also, neat, old rifles are both interesting and fun. Isn’t that really what brought most of us to rifle shooting in the first place?