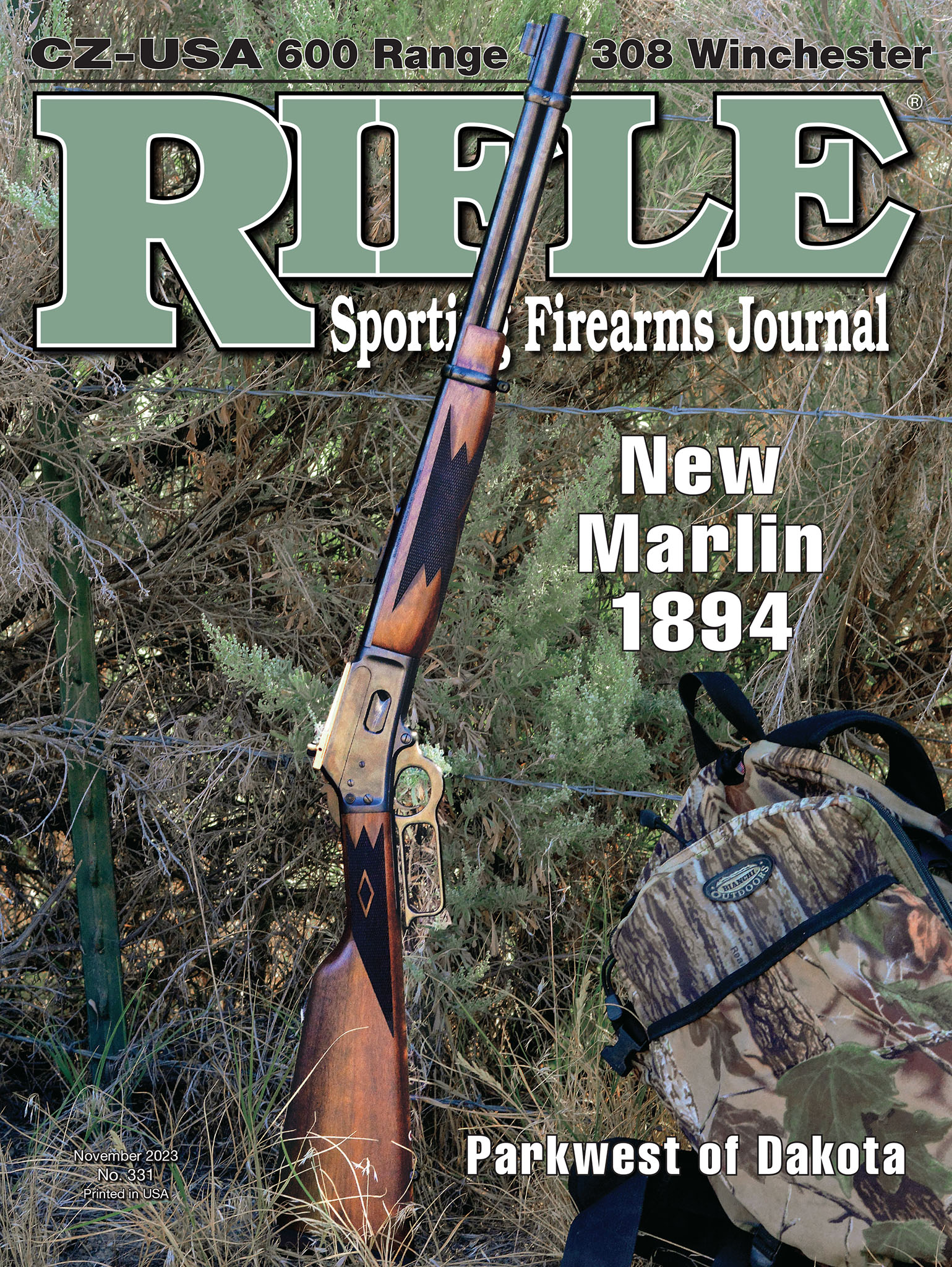

A British No. 4 Mk I 303 sniper rifle.

At the outbreak of World War II, the British found themselves short of all sorts of weaponry. Regarding snipers’ rifles, some Pattern 1914 303s mounted with obsolete scopes had been available at the beginning, but many were left behind at Dunkirk when most of the British Expeditionary Force evacuated continental Europe.

That may have been a good thing in that it forced British ordnance officers to start over in regard to snipers’ rifles with the newly-remodeled bolt-action 303s that were designated: No. 4 Mk I. These were still based on the Short Magazine Lee Enfield action, using 10-round detachable magazines and these rifles were test-fired for basic zeroing of their iron sights. (Blade fronts with intricately made peep rears.) Ones that were found to be especially accurate were set aside to become sniping rifles. As such, MOST were stamped on the connecting band with (T) meaning TARGET. Remember that word – MOST.

This view of the British No. 4 Mk I 303 sniper rifle shows the cast iron mounts and large thumb screws. These must be tightened periodically.

The world-famous firm of Holland and Holland (H&H) was chosen to turn No. 4 Mk Is into the T-versions. The left sides of chosen rifle actions were drilled and tapped for very sturdy cast iron scope mounts, which were fastened to actions by using two large thumb screws. Scope ring lowers were cast integral with bases and ring tops, likewise of cast iron, held scopes by means of four screws each at front and rear. Holland & Holland then bedded barreled actions into forestocks. At this point, it should be mentioned that most versions of 303 British bolt actions, since the late 1800s, had two-piece stocks held together by a steel coupling band. Buttstocks came in three lengths with the idea that they should be matched to soldiers’ physiques for the correct length of pull.

Because the No. 4 Mk I rifle was meant for use with peep sights, cheekpieces of wood had to be fitted to buttstocks to raise the rifle’s comb enough so soldiers could align their eyes properly with scopes. These were attached with two ordinary wood screws. It is interesting to read in Out of Nowhere by Martin Pegler that H&H carefully collimated scopes to set directly over rifles’ bores. Otherwise, adjustments of its No. 32 3.5x scopes would not give equal windage adjustments. For their work in building No. 4 Mk I rifles into the sniping configuration, H&H was paid about $5 each and by the war’s end, had converted 26,442. (Figures again according to Pegler’s book.)

A British No. 3 303 (above) is shown with a No. 4 Mk 1 (below) that was developed in 1942, and those that showed potential were picked for sniper rifle conversion.

One factor about the No. 4 Mk I(T) rifles that outclassed Axis foes’ sniping rifles is that the No. 32 scopes had windage and elevation turrets. Early No. 32 Mk I scopes had two minute of angle clicks, but later Mk II and MK III versions had one minute of angle clicks. For comparison, most German scopes on K98k 8mm rifles had elevation adjustments in scope turrets but windage was adjusted in their scope mounts. On the other hand, Japanese Type 97 6.5mm sniper rifle 2.5x scopes had no adjustments whatsoever. Likewise with most of their Type 99 7.7mm sniper rifles were also mounted with 2.5x and 4x scopes. Not until near the end of the war did German and Japanese ordnance people see fit to adopt fully adjustable scopes. (Both American and Soviet Union sniper rifle scopes were fully adjustable.)

This is a full-length view of Mike’s No. 4 Mk I 303 with a No. 32 Mk II 3.5x scope.

Also mentioned in Pegler’s book is that many British snipers used their adjustments in combat, having elevation charts at hand and making scope changes by judging wind conditions from experience. They hesitated to use the “Kentucky Windage” concept as was common with most other nations’ snipers.

Early in the twenty-first century, it became a passion of mine to build a World War II military rifle, carbine and handgun shooting collection. As things often happen, certain ones of that collection became favorites. This was especially true of sniper rifles used by the major combatant nations. One of the first ones I purchased was a No. 4 Mk I. Except for one detail, it was a perfect British sniper rifle for it had a No. 32 Mk II scope dated 1944 in cast iron mounts and rings with a wooden cheek pad. What it lacked was the magic (T) on the steel buttstock band.

World War II military cartridges are shown for comparison: (1) a German 7.92x57mm, (2) a Soviet Union 7.62x54mmR, (3) a British 303 and (4) a U.S. 30-06.

A friend likewise interested in World War II weaponry denigrated my new rifle as a “fake.” He said, “No (T); no authenticity.” However, I had found in my considerable reading about such things that MOST of the No. 4 Mk I rifles indeed had the (T) stamp in the proper spot, but I clung to the word MOST. Then I found something in the book

With British Snipers to the Reich by Capt. C. Shore. Therein, he wrote of forming sniper schools in western Europe near the end of the war. Prior to those training schools, British snipers were those infantrymen who chose to or were ordered to take a scoped rifle and go “hunting.” Capt. Shore related that some of these soldiers carried the idea of camouflage to the point of painting their rifles green. One day when having my rifle out in bright sunshine I happened to notice that in its stock’s pores there were visible tiny bits of green paint. That settled the matter for me. By the way, my rifle’s action is dated 04/43.

As with all World War II sniper rifles, the ones chosen by the British differed not at all from those issued to rank-and-file troops, except for the additions mentioned above. As standard for No. 4 Mk I rifles, they had 25-inch barrels with a 1:10-inch rifling twist, front sights “drift-able” in their dovetails, ladder-style rear peep sights graduated to 1,300 yards, bayonet lugs and brass (usually) buttplates. The length of pull on my No. 4 Mk I is 13 inches. The British made no effort to lighten their sniper rifles – mine weighs exactly 12 pounds.

Although its 10-round magazines were detachable, non-sniper rifles were meant to be loaded via five-round stripper clips. Of course, with a scope mounted directly over rifles’ actions this was not possible; meaning magazines were loaded a single round at a time. British doctrine was that each soldier issued a No. 4 Mk I rifle was given two magazines: the spare to be carried in his pack “just in case.” I would expect British snipers kept that spare magazine pre-loaded “just in case.” A benefit of how No. 32 scopes were mounted was that if said scope was damaged removing required only a minute or so in turning the large thumb screws. Then the sniper at least retained a fully-functional rifle.

The rounds Mike fired for this article included: (1) a Federal factory load with Sierra 180-grain JSP bullet, (2) a Sellier & Bellot factory load with 180-grain FMJ bullet, (3) a handload with a Sierra 174-grain HPBT and (4) a handload with a Sierra 180-grain JSP.

Let’s take a look at 303 British cartridge details. The case length is 2.22 inches while the nominal bullet diameter is .311 inch. This is interesting; the 303 British was adopted in 1888, powered by 70 heavily compressed grains of black powder under 215-grain jacketed bullets. In the early 1890s, the powder was changed to cordite with the same bullet. By 1910, the 303s were loaded with 174-grain FMJ spitzer bullets at about 2,440 feet per second (fps). That was the Mk VII load and it stayed in service until 1957. That’s correct: the British stuck with their 303 for 69 years, albeit they did toy with the idea of a 276 cartridge shortly before World War I. That idea was dropped with the British entry into hostilities in 1914. For a test, some years back, vintage 303, 30-06, 8mm Mauser, and 7.62x54R rounds dating from World War II, were gathered up for some load testing. All except the 303s fired well. Every 303 gave a distinct

click-pause-bang on pulling the trigger. I’ve followed that up with two other vintage lots of 303 military loads and had the same result.

Besides this sniper version, my handloading of 303 British has encompassed an SMLE No. 3, a standard No. 4 Mk I, a No. 5 “Jungle Carbine,” a Pattern 1914 and a Lewis machine gun. There is one caveat that handloaders must beware. Except for the Pattern 1914 and Lewis Gun, all the other 303s have rear locking bolts, and if brass is full-length sized for each loading, they will soon develop case splitting about three-quarters of an inch from the rim. Neck sizing only after a first fireforming round will alleviate this or at least delay it. However, this is an inconvenience when multiple rifles are using the same handloads. With my 303 sniper version, I use once-fired factory load cases or new brass for a loading or three, but at the first sign of that light ring around the case, they are pitched.

Speaking of factory loads, Winchester, Remington, Federal and Hornady all still offer 303 British factory loads as do European ammunition manufacturers such as Sellier & Beloit and Prvi Partisan. Speaking collectively, these have softnose hunting bullets of 150 to 180 grains or 174-grain bullets either HPBTs or FMJs. Rated velocities run from a high of 2,600 fps to about 2,450 fps.

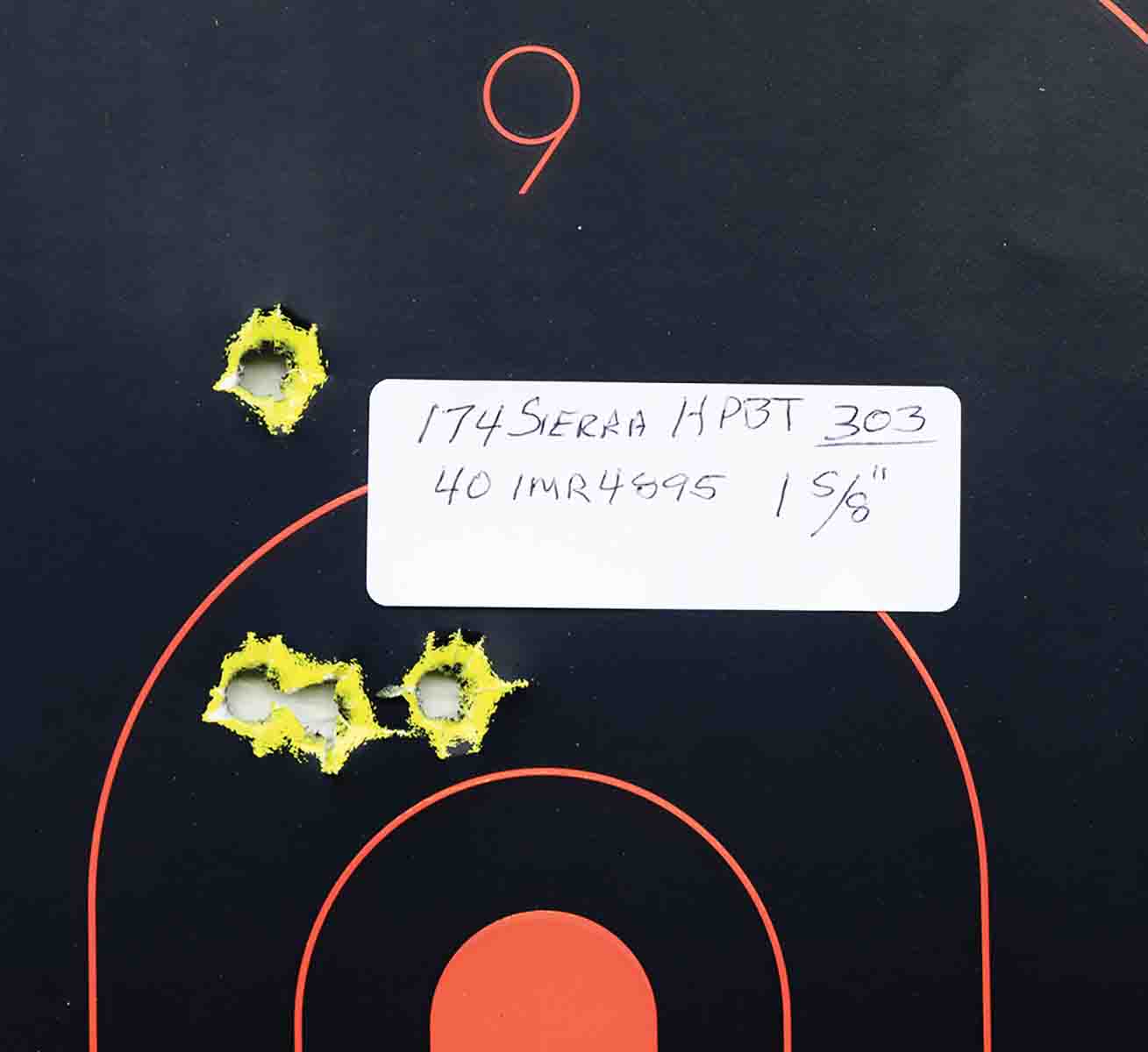

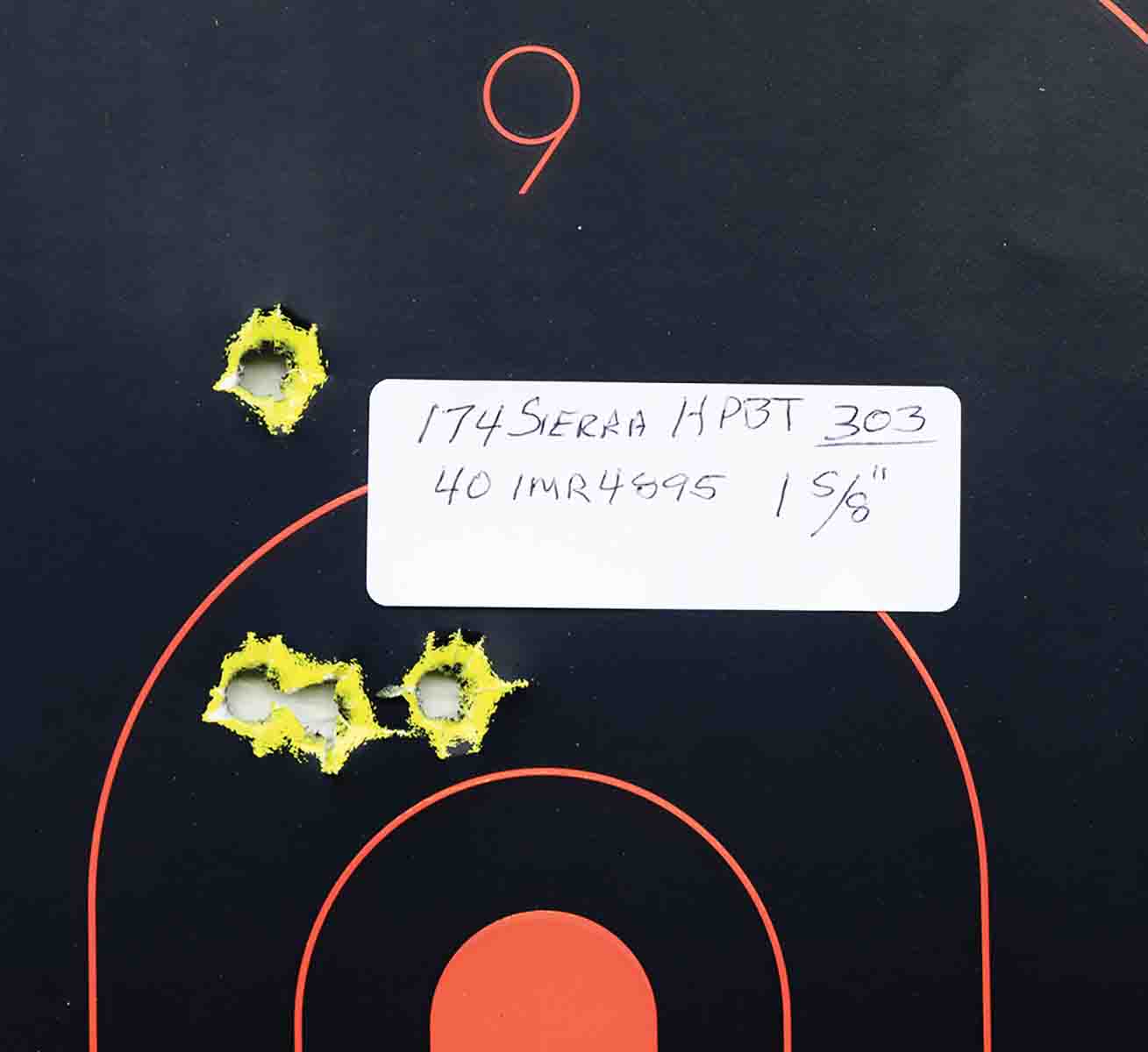

This is a sample group fired with handloads. Note the point of impact left of center.

A sample group fired with handloads. Again, note the point of impact right of center.

Suitable bullets for 303 British are available from 125 to 180 grains. I’ve tried most of them starting at 150 grains, but found the heavier ones better. My favorites have become Sierra and Hornady 174-grain HPBTs or FMJ in the latter case. However, Sierra 180-grain spitzers have also performed well. Again, speaking collectively, 303 British jacketed bullets from the various makers range from .3105 to .3120 inch but the majority are .3110 inch.

As for powders, there are so many suitable ones that it would be nigh on impossible to try all. Ones in the burning rate from IMR-3031 up to IMR-4320 give good results. The Lyman 51st Edition Reloading Handbook has a listing of all available smokeless propellants. My current favorite powders are IMR-4895 and Varget. They provide velocities at or even slightly above original military ballistics.

Mike’s 300-yard target using notes from a dozen years ago. The point of aim was center.

In books I’ve read about World War II snipers, it has been written that British snipers in northwest Europe felt their rifles were suitably accurate to 700 yards and more. My experience-based opinion is that my personal No. 4 Mk1(T) doesn’t deliver that sort of precision. Nor do I expect it to do because it is exactly 80 years old as I write this and while in good condition, it does show field use. My groups usually run in the 1½- to 2½-MOA range, which is perfectly suitable for my purposes. The group shown in one accompanying photo has four rounds in about 1 inch with the flyer being shot number five.

Here is something I noticed while shooting my 303 sniper rifle. Those large thumb screws must be checked regularly. One afternoon in group shooting, a nice cluster was followed by bullets stringing over about 6 inches. Sure enough, the thumb screws had loosened noticeably. Tightening them brought back the precision I’d come to expect.

Another fact I learned while group shooting was that different loads landed in different places. For instance, my handload of Sierra 174-grain JSP landed about 1½ inches left of center. Then, the load with Sierra 180-grain HPBT hit about the same distance right of center. Both were at about the same elevation. Since the No. 32 MK II scope adjustments seem as precise as when new, a simple click or two centers things up.

Mike’s 100-yard target using notes from a dozen years ago. The point of aim was six o’clock.

Before finishing, I’d like to add this. Prior to writing this piece, I’d not done any shooting with my No. 4 Mk I sniper for at least a dozen years. Taking it from the rack, I noticed a sticker I had placed on its buttstock. It said, “180 grain Sierra, 40 grains of IMR 4895, 100 yards #3, 200 yards #4 and 300 yards #5.” After shooting at paper to determine if the rifle’s zero was still on, I decided to aim at six o’clock on each of my 100, 200, 300 yard steel targets (18x24 inches). Dialing the scope according to the sticker’s settings I got first shot hits on each target. The 200-yard hit was a mite to the left but I’ll take the blame for pulling it. The other two shots were centered laterally. Then I switched to the Sierra 174 grain HPBT load and got almost identical results.

Considering that the Brits began the war with next to nothing regarding precision sniper rifles, they managed to develop a good one and built it in enough numbers to count.

.jpg)