Down Range

What Factory Letters May Reveal

column By: Mike Venturino | November, 17

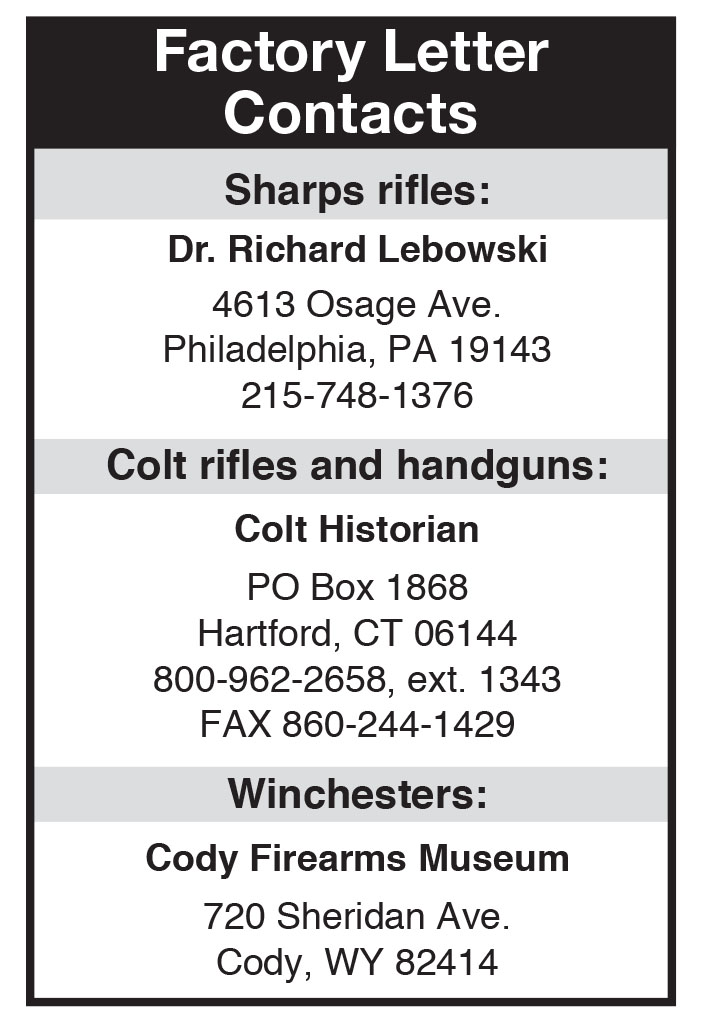

Anyone interested in shooting and/or collecting historical firearms should be aware of the benefits of factory letters of authentication. As an example, about 15 years ago I found an original Sharps .45-70 Model 1874 on an Internet firearms auction site. After a brief bidding war, I won the auction. When the rifle arrived it was in fair to good condition and worth the sum paid for it. Upon requesting a factory letter, I discovered it had been shipped to Dodge City, Kansas, the most desirable destination for most avid Sharps collectors. That piece of paper tripled the value of my new acquisition.

Usually listed on a Sharps factory letter are caliber, special order features, barrel length and shape, such as 30 inches, round, octagonal or half octagonal/half round. Occasionally the purchase price and accouterments, such as reloading tools, primers or sights, will be mentioned. Perhaps the most important information is to whom the rifle was shipped. Many rifles went to boring locations, such as New York City, Cincinnati or Chicago.

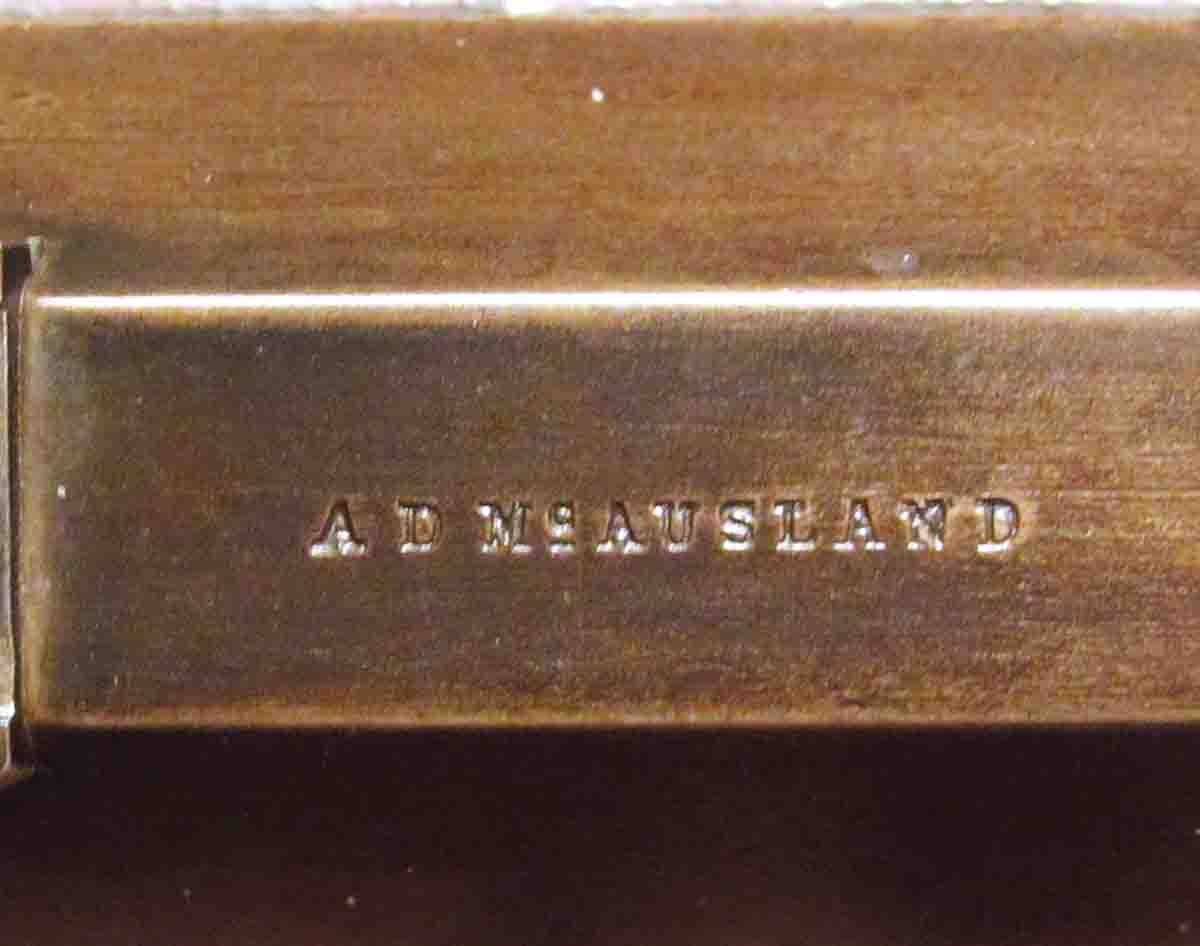

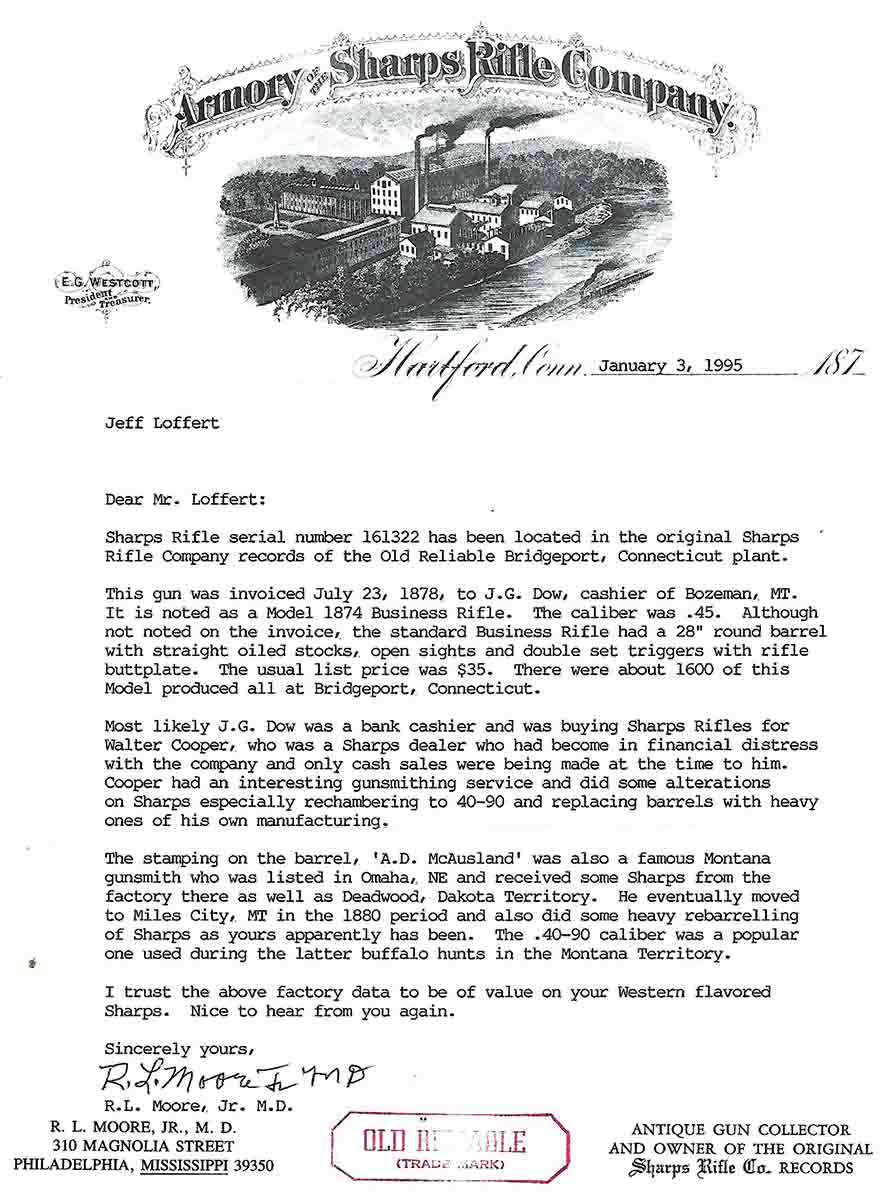

Not boring was the letter received by my friend Kirk Stovall of Bozeman, Montana. He purchased an old Sharps Model 1874 .40-90 Bottleneck. At that time, the factory records were owned by Dr. R.L. Moore Jr. of Philadelphia, Mississippi, and showed that this rifle had been shipped to Kirk’s hometown. Interestingly, it left the factory as a .45-70 but then had been remodeled by at least one well-known Old West gunsmith, and perhaps by two, both of whom were known for converting rifles to .40-90 BN.

Not all factory letter stories are quite so happy. Also in my collection is a Sharps Model 1874 in the Long Range No. 2 configuration. That means it has a 32-inch, half-round/half-octagonal barrel chambered for .45-26⁄10-inch case (aka .45-100 Sharps), a checkered pistol-grip stock with a steel, checkered shotgun buttplate and checkered single trigger. Research indicated only 292 were made, so I paid to have it lettered. The result came back: “Serial number is a blank in the factory records.”

Colt’s factory records are more or less similar to those of the Sharps Rifle Company. They usually list barrel length, finish, stock material and shipping destination. Even modern Colt firearms can be lettered. For instance, in 1984 I ordered a custom .45 Single Action Army revolver, and its factory letter showed that it had been sent directly to my Montana address. Once I purchased a Colt Lightning pump-action .38 WCF (.38-40) short rifle. There was some debate between me and a friend about whether it was actually made with a 20-inch barrel instead of the customary 26-inch length, or if it had been cut back after leaving the factory. To settle the matter, I bought the Colt letter only to have it say, “Barrel length not recorded.”

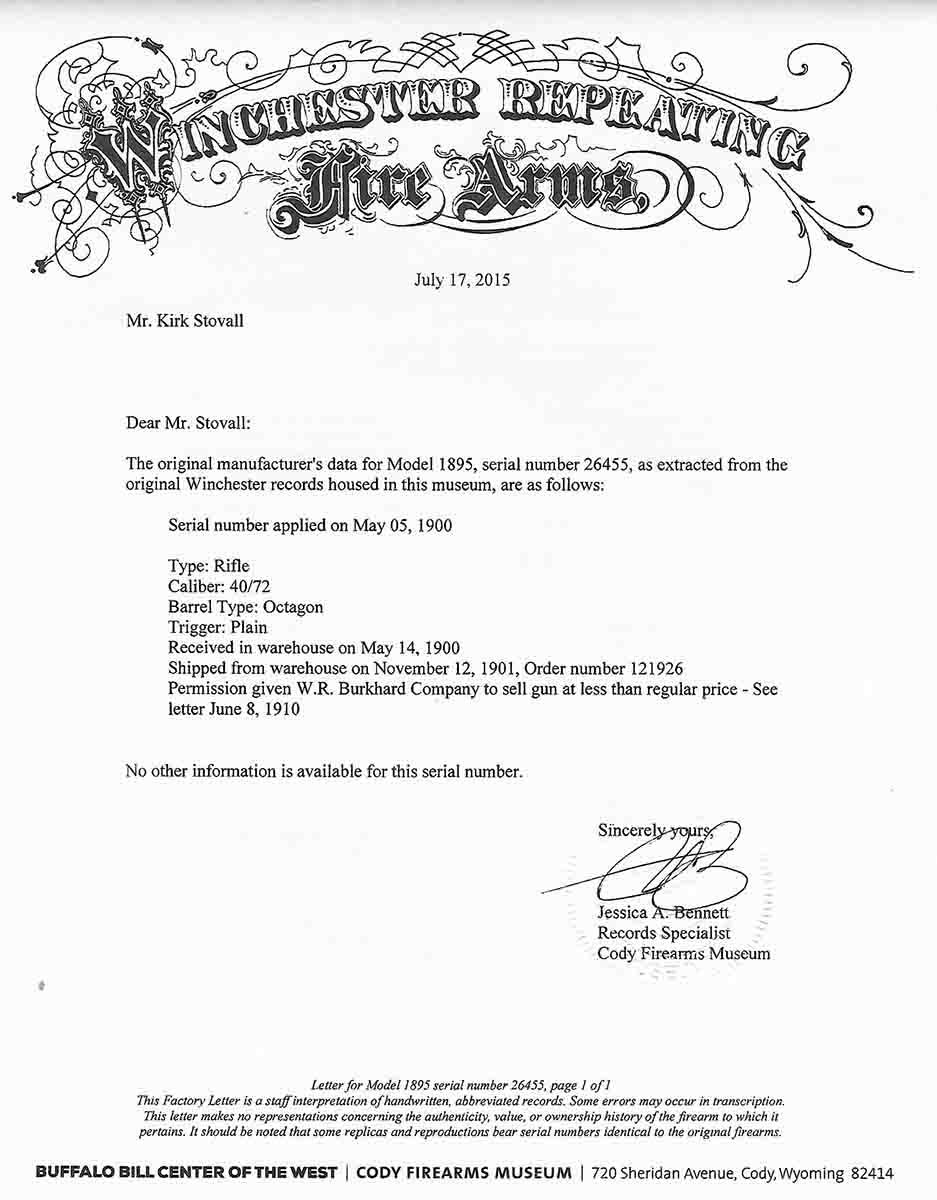

Winchester Repeating Arms factory records are now in possession of the Cody Firearms Museum. The possibility of the company’s letters showing historical destinations is small. The only mention of destination I’ve ever received was that a Model 1873 .32 WCF was sent to Montgomery Ward. Also, the records cease somewhere in the early 1900s, so no data exists for more current Winchesters. The information available usually contains configuration, date received in the warehouse, date shipped from the warehouse, caliber and special features. As to configuration, that means rifle, carbine or musket, and special features include things like a nonstandard barrel length or octagonal instead of round, or a checkered stock. If, however, there is some interesting tidbit in Winchester’s records, it will be included. Kirk Stovall learned this when his letter showed that a Winchester dealer contacted the company, asking permission to reduce retail price on a Model 1895 .40-72 he had in stock. (That was in 1910. Perhaps by then a Model 1895 chambered for a black-powder cartridge was hard to sell?)

Secondly, many late-1800s and early-1900s Winchesters were hard-used and often abused. Restoring them is perfectly acceptable as opposed to counterfeiting. Records in the Cody Museum can give guidelines as to how a particular Winchester started out.

Factory letters can range in price from a small fee up to $150 for some Colt or Sharps letters. At worst, they may show a gun has been “messed with,” but once in a while they prove it to be something special.