Lock, Stock & Barrel

Practical Hunting Reticles

column By: Lee J. Hoots | March, 20

For some strange and unknown reason, the term “aiming solutions” has apparently replaced the traditional “riflescope” and “reticle.” The word “crosshairs” has all but been forgotten in modern marking-speak. Language has changed, for better or worse, but “sighting solutions” continue to evolve.

Flip through any shooting/hunting gear catalog or peruse the Internet, and it’s almost difficult to find a traditional riflescope. Instead, catalogs and cyberspace are full up with a mind-boggling assortment of options with an extensive and often dizzying array of so-called solutions. Reticles now feature a mixture of dots, numerals, letters, dashes and hash marks, symbols, unrecognizable doodads and all sorts of other potential clutter. Of course, much of this has been brought about in the last 10-plus years or so due to increasing interest in long-range target shooting (and tactical applications) for which such reticle enhancements are no doubt useful.

Most hunters, however, are better served by less sophisticated options. Unless purposely trying to shoot game at some unrealistic range, something most experienced sportsmen frown upon, as do I, a far more simplified scope is often desirable when pursuing big game. We can get along quite nicely with a standard reticle or a simple lighted dot if a quick shot is needed when a buck jumps from cover and takes off for parts unknown, or when a bull elk ghosts into view across a canyon at the end of the day.

As an example, while on public land in New Mexico a .280 Remington was used to shoot a dandy bull. The elk were out there at 400 yards, about as far as I would consider shooting at any game that was not previously wounded, and even in the best situation a 400-yard shot requires careful deliberation, but not necessarily a fancy “solution.” The scope on the rifle was a short Swarovski Z8i 1-8x 24mm (set to 6x) with a lighted dot reticle in the center of crossed wires, a boon in the waning light. Before it was returned to the manufacturer, that Austrian-designed scope also worked well on a big free-range aoudad ram shot with a fancy but moderately-priced Mossberg Patriot Revere .270 Winchester, and soon after a white-tailed buck in Wyoming. Both were much closer than the New Mexico bull.

Between cluttered reticles and standard duplex (actually a Leupold trademark: Duplex) designs, there are reticles that provide hold-over options that work quite well without cluttering up a hunter’s field of view or requiring twisting and turning turrets to accommodate distance and wind.

I have hunted enough around the country and in Africa, Canada, Europe and Argentina to know that shots on game beyond 400 yards are almost always unnecessary. Furthermore, at least a half-dozen outfitters/guides I know have punctuated the fact that wounding loss is a problem at extended range – most of them will no longer allow unnecessarily long shots to take place under their watch.

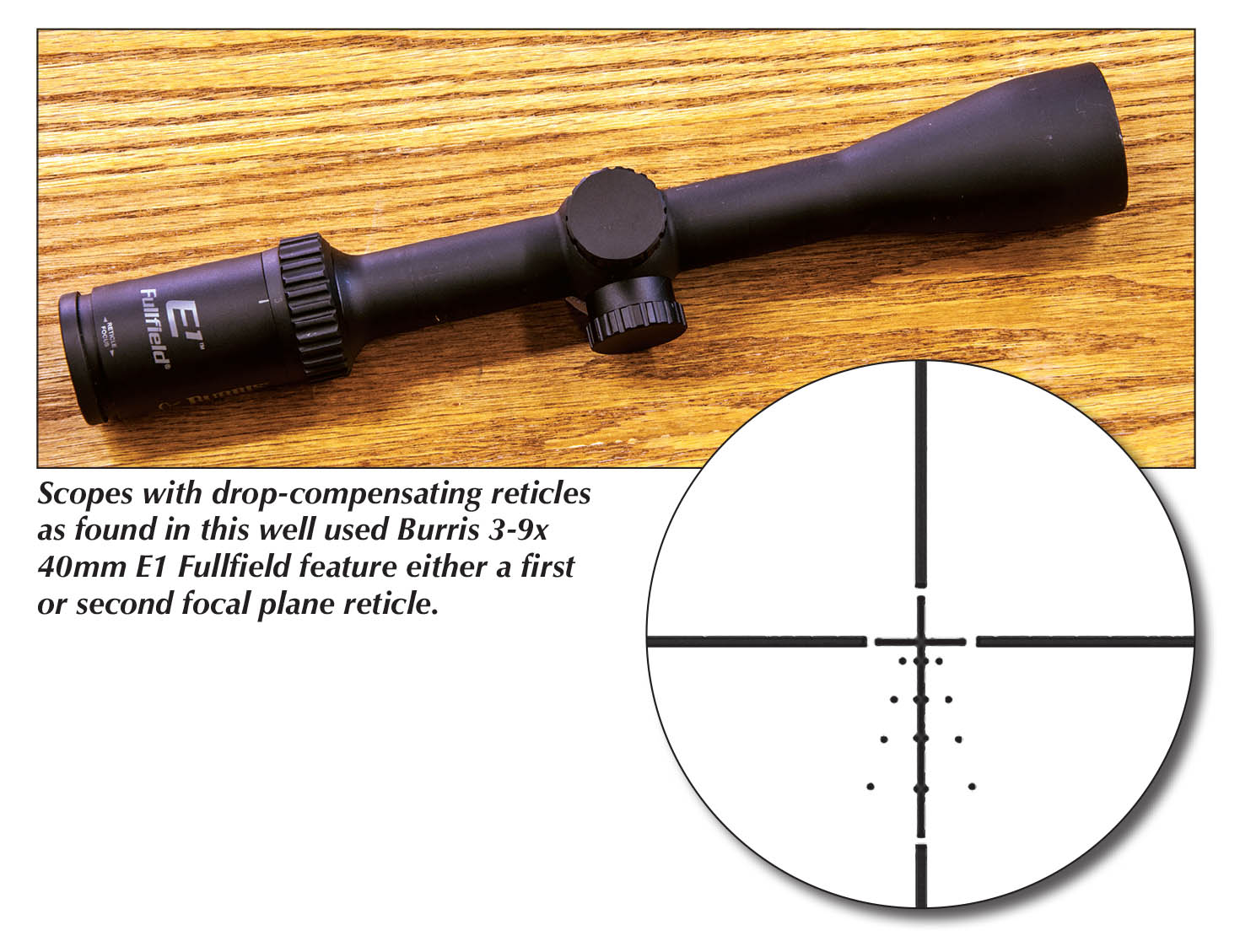

There are many good riflescopes with simplified hold-over reticles. They are easy to use and some are not overly large so they don’t burden a sporting rifle’s balance and weight. Most manufacturers offer one or two versions, and I’ve used several of them with good results, including scopes by Burris, Leupold and other optics companies. When it comes to modern techno-reticles, basic designs usually cost less and make the most sense for practical field applications.

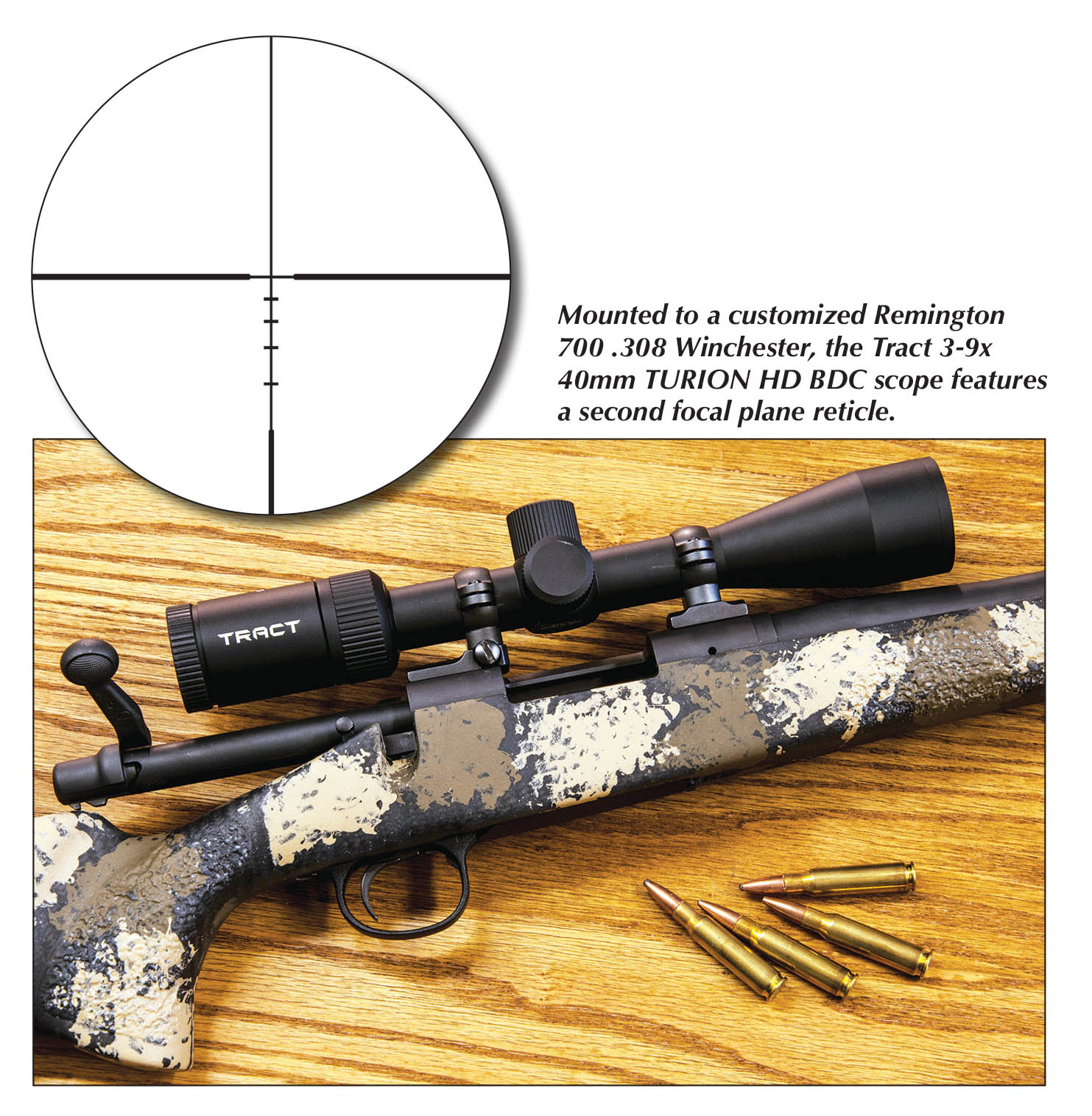

One new example is a second focal plane Tract 3-9x 40mm TURION HD I’ve recently started testing on a Remington 700 .308 Winchester with a cut-rifled barrel made by Danny Pedersen at Classic Barrel & Gunworks in Prescott, Arizona (cutrifle.com). The TURION HD features a ballistic drop compensation (BDC) reticle with unobtrusive descending holdover bars. Other features include high definition multi-coated Schott glass and 4-inch eye relief, all in a one-piece tube (tractoptics.com.)

When Burris introduced its Ballistic Plex reticle around the year 2000, it introduced an entire generation to the idea of “aimed holdover.” While certainly not the first of its kind, the scope included a standard crosshair with three horizontal bars in descending order on the bottom half of the vertical wire. The bottom post also acted as an aiming point. In theory, all that was needed was for the rifle to be zeroed at 200 yards, and each descending horizontal bar represented holdover in 100-yard increments. The bottom-most bar could be used for a 500-yard hold. However, this is all theoretical because no individual cartridge could match up exactly with a given rifle/scope setup, but it still works well with most common hunting cartridges after a bit of practice.

Experimenting with this scope, and others that came along later, led me to become quite fond of them once it was realized most such scopes are designed to be used at their highest magnification – and even then, point of aim and point of impact don’t always jive. They may be close, but close doesn’t always cut it. As noted, bullet velocity varies widely from brand to brand and from rifle to rifle, so it makes sense to practice while at the same time figuring out how magnification, say, 3x compared to 9x, may change impact.

Leupold’s Long Range Duplex Reticle is another favorite. Both older and newer examples reside on several hunting rifles in my safe. One is an older VX-II 3-9x 40mm variant atop a Ruger Hawkeye 6.5 Creedmoor with a 26-inch barrel purchased 12 years ago when the cartridge was new. My notes indicate that handloads in Hornady cases consisting of either Nosler 130-grain AccuBond or Hornady 129-grain InterBond bullets seated over an appropriate charge of Winchester 760 produced five-shot groups that could be covered with a nickel. Respective powder charges and velocities were 45.2 grains (2,989 fps) and 44.3 grains (2,880 fps).

That scope-and-rifle combination was eventually tested with the AccuBond handloads at the NRA Whittington Center in Raton, New Mexico. Zeroed at 200 yards, from sand bags two shots at 100 yards landed about .5 inch apart and 2 inches above point of aim, according to my notes. At 200 yards shooting at a coyote silhouette with a 5-inch hole in the kill zone, a dead hold with the top crosswire put a bullet through the opening. A steel plate at 300 yards was dead-centered using the first dot down. At 400 yards another plate was center-punched using the next lower reticle dot.

After shooting a pronghorn at about 80 yards, a second shooting session two days later on the center’s silhouette range revealed more evidence of how the reticle can help in a hunting situation where shots can be extended. Pigs at 300 meters were easily tipped over using a dead hold with the 300-yard dot. Turkeys at 385 meters were tipped over with a hold along the back of the target using the 400-yard aiming point. Rams at 500 meters were toppled with the bottom reticle post held a few inches above the top of the target.

Some years later I mounted a slightly newer Leupold VX-2 3-9x 40mm scope with LRD reticle to a near identical Ruger Hawkeye .25-06 Remington and got very similar trajectory cohesion. That scope is now mounted to a Weatherby Mark V .240 Weatherby Magnum. Because such scopes are simple enough to use in the field given a little down range experimentation and are much quicker to use when a deer erupts unexpectedly from its bed in sage brush, I’ve built up quite a selection. After having a custom .260 Remington made by Danny Pedersen about eight years ago, it was topped off with a Burris 3-9x 40mm Fullfield II that still works well, and I intend to use a similar scope on a new Bergara Highlander .308 Winchester bolt rifle with a curt, 20-inch barrel.

Scopes with various hold-over reticles like those discussed here are provided with their reticles in either the first focal plane (crosshairs at the front of the erector tube) or second focal plane (crosshairs in the rear of the scope.) My preference is a second focal plain reticle, the apparent size of which does not change as scope magnification and image is increased or decreased. This is purely due to having grown up using second focal plane designs.

One disadvantage is the fact that hold-over or windage marks no longer correspond with bullet impact at various yardages when magnification is increased or decreased. One way to get around this potential problem is to zero the rifle with the scope on its highest magnification, since most long shots at game are taken after magnification has been topped out. A big-game hunter can carry his rifle at lower magnification and still shoot out to 200 yards or so with confidence. When a long shot is the only shot, it takes but a second to turn up magnification.

A fixed-power scope with a drop-compensating reticle presents zero complications because there is no magnification adjustment to fool with. A Leupold FX-II 6x 36mm on a CZ 550 .30-06 is a lightweight option on a relatively heavy rifle, and it’s two descending dots and bottom post just about mesh perfectly with 165-grain bullets out as far as I would care to shoot a bull or buck that was not previously wounded. As new “solutions” are brought forth, fixed-magnification scope options are unfortunately becoming increasingly rare. Since I don’t shoot the .30-06 much, the FX-II is a likely candidate for the Bergara .308.

There are advantages to a first focal plane reticle, however, especially when using the current crop of new “shooting solutions.” As magnification is increased, hold-over or windage holds remain the same at any magnification. As power is zoomed up, the apparent size of the reticle is equally increased. I’ve seen rare scopes with such great magnification abilities that when cranked all the way up, the outside extensions of the crosshairs cannot be seen clearly, or at all, sometimes negating the use of windage holds. This is probably not a great problem for hunters who only shoot big game at realistic ranges, but it can be when shooting varmints or small game at a great distance in high wind conditions.

Regardless of which type of scope is chosen, first or second focal plane or fixed magnification, practice in field conditions is the best way to learn the nuances of any scope. Minor tweaks in zero are sometimes necessary to get the full benefit of drop compensation. Such scopes also need to be mounted perfectly plumb to a rifle’s receiver.