Vintage Sporting Rifles

Lessons Learned in the Field

feature By: Mike Venturino Photos by Yvonne Venturino | March, 20

More deer and a couple pronghorns fell to that rifle. I liked it so much that I presented it to the rancher’s son when he became old enough to hunt. Last I heard, he is still using it. Many other finely accurate, scope sighted, bolt-action rifles came and went, and they also accounted for deer and pronghorn and even a few elk.

Never will I say that hunting was physically easy for me. Without horses I wouldn’t have made it to some of the areas where I bagged game, but actually hitting game with scoped rifles was relatively easy. I avoided stunts like shooting to excessive ranges or trying to hit pronghorns that were flat out running. Certainly there were misses, usually due to over eagerness or over confidence.

They reduced practical ranges, increased the amount of light needed to see iron sights and for the most part, eliminated the idea of dropping your quarry in its tracks. Stated simply, vintage sporting rifles made big-game hunting far more difficult. The first year I carried peep or open sighted rifles, never did I see an animal close enough to try shooting. Approximately 100 to 150 yards in perfect conditions was my self-set limit.

The second year went much better and both a bull elk and a mule deer buck fell to my “Big Fifty” Sharps, a Shiloh 1874 reproduction .50-90 (.50-2½ in 1870’s terms.) Both of those critters were inside 100 yards. Success increased my interest in using vintage sporting rifles and also provided an excuse to buy more.

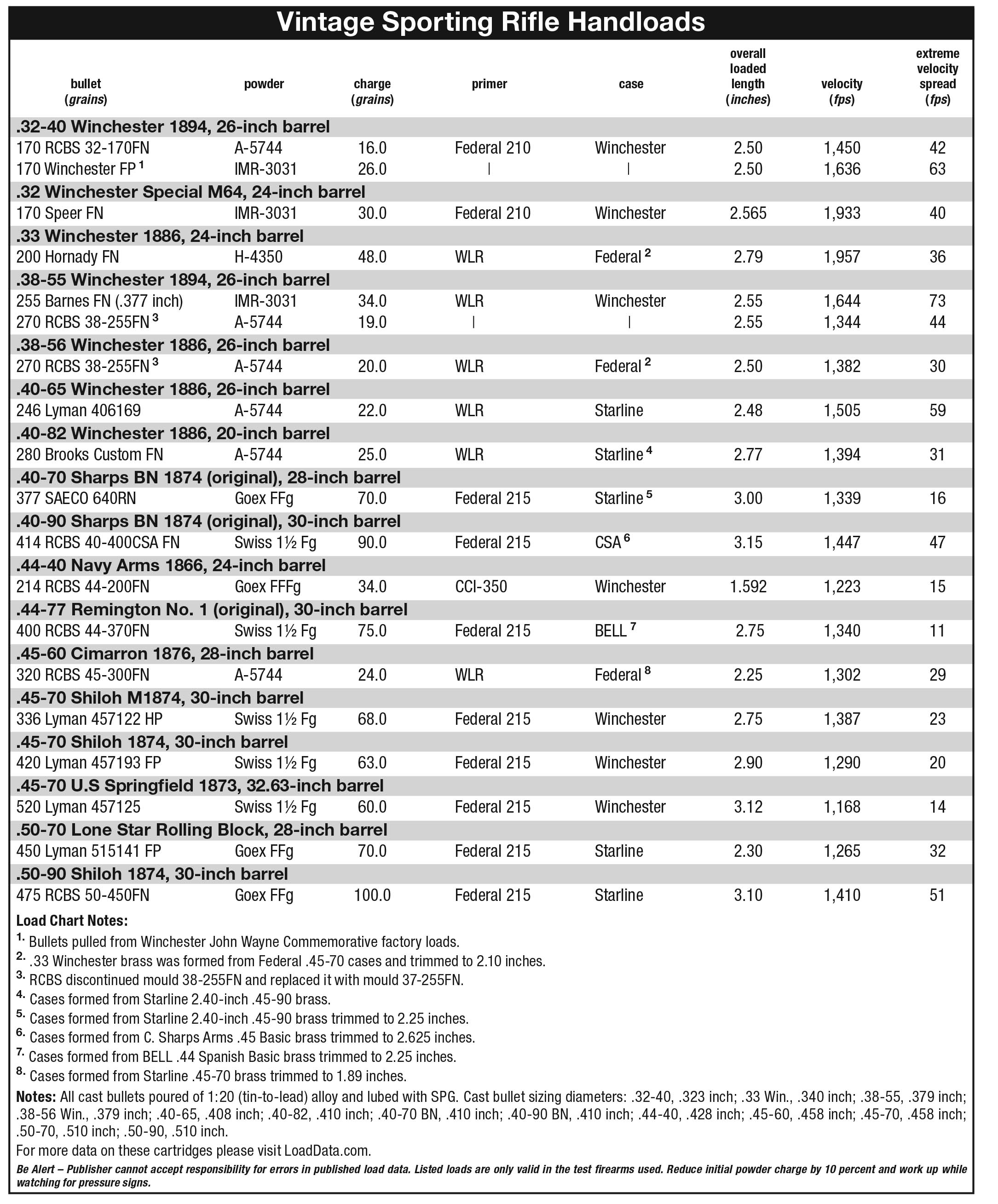

Over my active hunting years with vintage rifles, I shot animals as small as South Texas whitetail does (depredation) and as large as one-ton bison bulls plus a half dozen head of African game. The cartridges used were .33 Winchester, .38-55, .38-56 WCF, .44-40, .40-70 Sharps BN, .40-82 WCF, .40-90 Sharps BN, .44-77, .45-70, .50-70, .50-90 and perhaps others I’m forgetting. Both personally cast bullets and factory jacketed versions were used over black powder and smokeless propellants. I learned much.

Before becoming a true believer in the merits of black powder, most of my vintage sporting rifle shooting and hunting was done with smokeless propellants and jacketed softpoint bullets. JSPs are not always available for vintage cartridges; sometimes one must improvise. For example, when I wanted to hunt with a Winchester Model 1894 .32-40, proper .322/.323-inch flatnose softpoints weren’t available. Some of the very mild Winchester John Wayne .32-40 Commemorative factory loads were purchased. Their proper size 165-grain bullets were pulled, powder was dumped and replaced with heavier charges of IMR-3031 and the bullets were reseated. The same thing was done using likewise mild Winchester .38-55 factory loads with 255-grain flatnose JSPs. Deer and antelope fell to Model 1894s in both calibers.

When Yvonne and I decided to go to Africa, I took along a Shiloh Sharps Model 1874 .40-70 BN and a Winchester Model 1886 .33 WCF. The former’s smokeless handloads used 400-grain Barnes softpoints and the latter’s rounds included Hornady 200-grain flatnose softpoints. The only bullet recovered from African plains game was one of the 400-grain Barnes bullets. It traversed a Kudu diagonally from its right shoulder to its left hip, where it was found under the skin, expanded to .74 inch.

Ironically, a well expanded 255-grain softpoint nearly cost me a mule deer when fired from a Winchester Model 1894 .38-55. One late November day in Montana, I spotted the buck standing broadside at almost 100 yards in a level area filled with boulders and high sagebrush. At the shot, it ran and literally disappeared. Yvonne and I could find no trace. The snow was full of deer tracks so the buck’s just blended in and there was nary a trace of blood. Yvonne said, “You must have missed.” I was sure it was hit and finally spotted the buck lying behind a boulder stone dead from a heart shot.

With cast bullets over smokeless powders there comes a near “Catch 22” problem, especially with the smaller .30 to .38 size cartridges. If the bullets are hard enough to avoid leading barrels they will not expand. If they are soft enough to expand, they won’t be accurate due to leading, plus stripping on rifling. The easy answer is flatnose designs for cast bullet hunting. RCBS offers a complete array of good flatnose designs. I transitioned to the RCBS mould 38-255, which drops 270-grain bullets when poured of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy. I used it on deer in both my .38-55 and a Winchester Model 1886 .38-56 with good results.

With larger bores, lack of penetration isn’t a significant problem. From .40 to .50 caliber, velocities of about 1,200 to 1,400 fps with either type of propellant are perfectly adequate. That means bullets as soft as 1:20 to 1:40 (tin-to-lead) work well. Bullets from 370-grain .40 calibers on the light side to 550-grain “Big Fifties” on the heavy end will usually give good penetration, even on one-ton bison bulls. With such bullets, higher velocities than just mentioned will only result in larger divots in the ground on the game’s offside.

Size of the quarry is also a factor. On that South Texas depredation hunt, we were only allowed does and spike whitetail bucks, and those critters are small. For several I used Lyman’s 457122, a 330-grain hollowpoint. Fired over blackpowder at velocities around 1,300 fps, it worked well. Back home in Montana, with complete confidence in that load I shot a moderate size mule deer buck at about 75 yards. Its does took off at the shot and the buck followed but I could tell it was hit. After a bit of a walk I found the buck, still alive with its head up. A head shot finished the deal. My 330-grain HP cast bullet’s nose had peeled off from the solid base, with the solid bottom section making it to the off shoulder. After that I used at least 400-grain or heavier flatnose bullets in .45-70s.

Some readers might be thinking, “But, the faster a bullet travels, the flatter its trajectory.” Of course that is true. However, remember the range limit I set. With iron sights – either open or peep – at much pass 100 yards front sights begin to cover a significant portion of an animal’s body. I know because deer hang out on my private range year-round and I’ve been able to sight on them with many bead and blade front sights from 50 to 200 yards.

Personally speaking, on a vintage sporting rifle a finely adjustable aperture rear sight is a poor choice. One reason is that shots on game can occur near instantly, and the window of time available isn’t enough to deal with sight adjustment. Another is weather. Once I had a Vernier tang sight on an original Sharps Model 1874 .44-77. The temperature was below 0 degrees Fahrenheit. The shot required moving the sight’s eyecup. It might as well have been super glued in place, for it was frozen solid.

As my eyes began to age, I mounted a long tube 4x scope by the now defunct RHO Instruments Company on two of my favorite Shiloh Model 1874 .45-70s. I could see much better, but the scope gave me a false sense of security. In my mind, practical shooting distance had increased greatly. For that reason, when going after a free-ranging bison cow I was willing to try shooting at it at a lasered range of 261 yards. Hitting it was no problem, but the cow just stood still and soaked up several 520-grain roundnose bullets (Lyman 457125). Some penetrated completely and some did not. Not once did it even look around to see what was bothering it. Finally, the cow dropped, and the experience taught me another lesson in over-confidence.

A problem encountered in hunting with vintage sporting rifles is a lack of sling swivels on most. Hand carrying a vintage rifle in very cold weather will cause even gloved hands to freeze. When trying to carry my Winchester

At this point I must admit something: Some years back my health began failing and I had to give up hunting. So I developed what I call a “surrogate hunter.” That’s my good friend Kirk Stovall. I’ve never known a more avid hunter, and even better, he has a collection of vintage rifles that puts mine to shame. So we have a sort of “trade” worked out. He gets a vintage rifle in whatever chambering his heart desires, and I help him get it shooting well. Then when he bags game, as he invariably does, I get photos to use.

For instance, in 2019 he said he had recently purchased a Winchester take-down Model 1894 .32-40. With a little advice from me, he had it shooting nicely and got a nice mule deer at about 100 yards. I got a good photo for this article. It’s a system that works for both of us.

Author’s Note: A correction is needed for my article “100 Years of Infantry Rifles” in the Rifle No. 308, (January 2020) issue. In the load chart concerning the 7.62mm NATO I mistakenly typed 23 grains of Varget powder with 155-grain Hornady bullets. The actual charge should be 45 grains.