.50-70 "Trapdoor" Springfield

An Old Rifle Back in Use

feature By: John Barsness | May, 20

In 1865 the United States government was pretty broke due to an internal war that lasted four years, but to be prepared for other possible conflicts the U.S. Army needed to keep up with the latest technological trend, self-contained rifle cartridges. These started appearing long before the War Between the States, the inevitable result of the development of the percussion cap, which appeared in the early 1800s when a Scottish Presbyterian minister, Rev. Alexander John Forsyth, developed a fulminate-based compound that exploded when sharply whacked. This resulted in caplock rifles, which immediately began to replace flintlocks, and eventually self-contained cartridges.

Some other armies around the world had already converted to cartridge rifles, though many were still relatively primitive, such as the paper cartridge for the Dreyse “needle-gun,” a bolt-action single shot adopted by Prussia in 1841. The percussion cap was attached to the base of the .60-caliber bullet, and the Dreyse’s long firing pin (“needle”) pierced the paper and traveled through the powder to ignite the cap.

While a few cartridge rifles, including repeaters such as the Spencer lever action, had been used during the Civil War, the overwhelming majority of Union soldiers carried the Springfield Model 1861, a .58-caliber caplock muzzleloader, and its later, minor model variations. The U.S. Army had more than a million of these already obsolete rifles and decided to convert them into breechloaders at far less cost than producing new rifles.

Several people came up with workable conversions, but the winner was developed by Erskine S. Allin, master armorer at Springfield Armory. His design removed a few inches off the top of the rear end of the barrel; the gap was then fitted with a steel breechblock hinged at the front (hence the nickname “trapdoor”) containing an angled firing pin. Allin personally patented his system in 1865, unbeknownst to Gen. Alexander Dyer, Chief of Ordnance, but Allin assured the general the Army could use his design without paying royalties.

The first trapdoor Springfields were 5,000 muzzleloaders chambered for a .58 rimfire cartridge loaded with a 480-grain bullet and 60 grains of black powder. These rifles were called the Model of 1865, but unfortunately the .58’s ballistics were comparatively wimpy due to the pressure limitations of the copper rimfire case, while the smaller parts of the breechblock were complicated and failed too often.

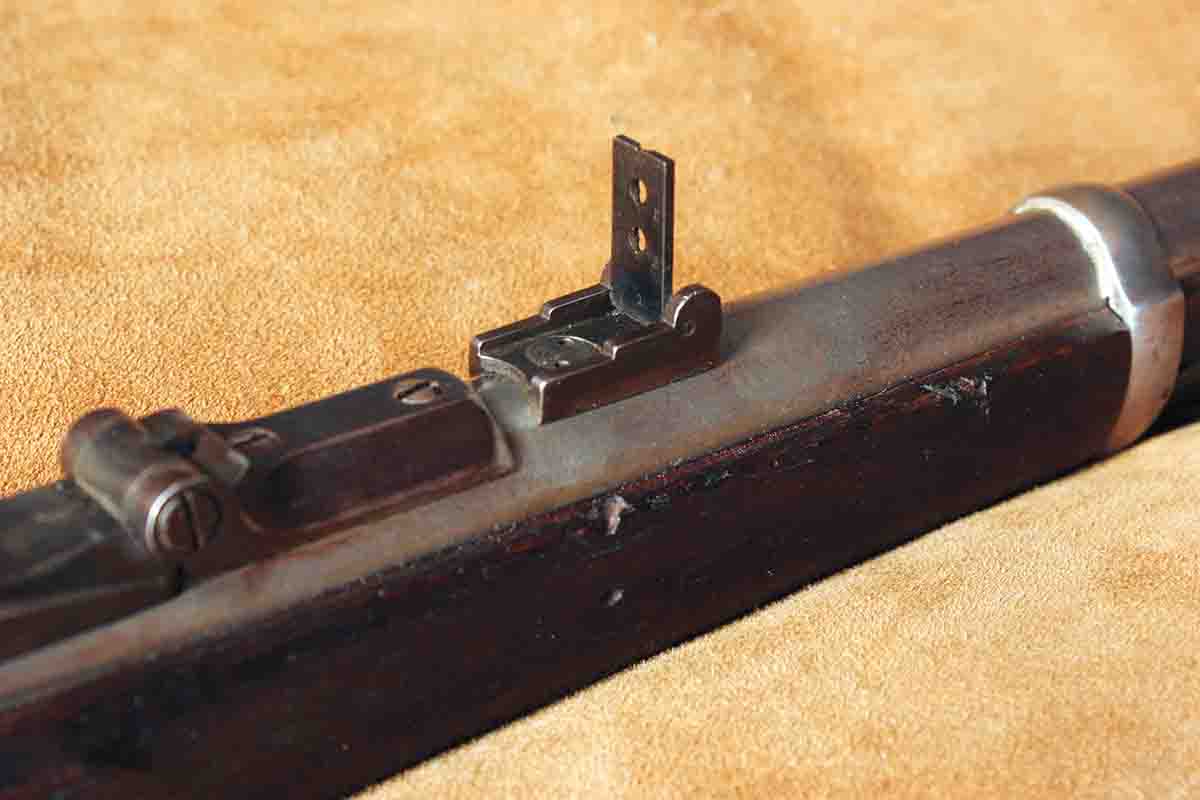

Consequently, in 1866 the second Allin conversion appeared with a less complicated breechblock, including a U-shaped spring extractor that flung fired cases out of the chamber, whereupon they hit a wedge-shaped steel block in the “trough” behind the chamber, launching them into the air. The .58-caliber barrels were relined to .50 caliber and chambered for the new centerfire .50-70 cartridge using a 450-grain bullet and 70 grains of Fg black, resulting in 1,260 fps from the 36.6-inch barrel. (The original barrel length of the muzzleloaders was 40 inches, but the breechblock reduced that to 36.6 inches.)

The .50-70 conversion was a success, and its first major action was the famous Wagon Box Fight of 1867 in present-day Wyoming, where a handful of soldiers from nearby Fort Phil Kearny, along with a few civilians, held off several hundred Indian warriors led by Lakota (Sioux) Chief Red Cloud, thanks in part to the rapid repeat fire from the cartridge rifles. The .50-70 conversion went through several variations from 1866 to 1870, when both an infantry rifle and cavalry carbine were produced.

The Model 1870 was replaced in 1873 by a new trapdoor Springfield, which was not a converted muzzleloader. Instead it featured a separate barrel chambered for a new .45-caliber round, screwed into a trapdoor “action.” The .45 cartridge was loaded with a 405-grain bullet and 70 grains of black powder for infantry rifles – the reason it became known as the .45-70 – or 55 grains of powder for the lighter cavalry carbine.

The .45-70 trapdoor also went through several variations, the last the Model 1889. Some were still used by the U.S. military after being “officially” replaced in 1892 by a smokeless .30-caliber cartridge chambered in a Krag-Jorgenson bolt-action repeater. In fact, due to a shortage of Krags, some secondary army units used .45-70 trapdoors during the Spanish-America War of 1898.

My interest in trapdoor Springfields began with a .45-70 belonging to my father Jack. While in college, shortly after World War II, he joined a fraternity which (like many in those days, and even now) was headquartered in a big Victorian-style house. One day Jack and a fraternity brother decided to explore the attic, which apparently hadn’t been opened in years.

Among other dusty items was a wooden case of Model 1884 trapdoor rifles that had been used for the school’s ROTC program before more modern rifles (such as .30-40 Krags) became avail-able. They each kept one rifle and gave the rest away to a local museum – which probably sold them, since even well into the twentieth-century used trapdoors were far from rare.

After my father passed away, I ended up with his small gun collection because nobody else in the family was interested. The .45-70 did not shoot very well with black powder and cast bullets, due to a rough bore that was only slightly corroded but with large reaming marks. At first, I used IMR-4895 and 405-grain Remington jacketed bullets but switched to cast bullets and Accurate 5744 smokeless powder.

Eventually my overall interest in trapdoor Springfields started growing, partly due to working for an archaeological and historical research firm in the early 1980s. My primary job was cartographer, but I also got to take part in some field surveys, including one in eastern Montana, where the last big bison herd of the nineteenth-century roamed around, often into North Dakota.

The herd was almost totally wiped out in the early 1880s, but bones are still occasionally found, along with associated artifacts. Among the interesting stuff our field crew found was a fired .50-70 military case, one of the “inside-primed” versions using a Benet primer integral to the case. Despite the fame of Remington Rolling Block and Sharps “buffalo rifles,” some historians believe .50-70 Springfields accounted for far more bison, primarily because of the abundance of trapdoors. Among those who used a Model 1866 .50-70 was “Buffalo Bill” Cody, when he hunted for meat to feed workers during the construction of the Kansas Pacific Railway.

Eventually a .50-70 trapdoor appeared at Capital Sports & Western Wear in Helena, Montana, where apparently the head of the gun department, Dave Tobel, could read my mind when I walked in one day. Dave immediately grabbed a long gun from the vertical rack behind the counter, where they often keep the really good stuff.

At first glance, I thought it was an old muzzleloader, one of Dave’s personal enthusiasms, but of course it was a .50-70 with a dinged-up stock and almost no bluing – but a pretty shiny bore. The front of the breechblock, just behind the hinge, was stamped 1866, indicating a first-year conversion, alongside the “eagle head” stamp. The lockplate was stamped 1864.

The “bonding process” (as a friend calls the interval between encountering a rifle and deciding to buy it) took maybe two minutes, partly because Dave offered to include 20 pieces of brass from his personal .50-70 stash, a few already loaded with cast bullets and black powder. (He also suggested it was used in the Wagon Box Fight, whereupon I looked sharply at him, whereupon he grinned and said, “Well, it could have been.”)

The rest of the gearing-up took slightly longer. Andy Larsson of Skinner Sights in St. Ignatius, Montana, got wind of my “new” rifle and offered to donate a set of Lyman .50-70 dies he wasn’t using. After measuring the bore, I ordered some new Starline .50-70 cases, and 450-grain cast flatnose bullets from Montana Bullet Works (MBW), sized .512 inch in diameter. These bullets are from a discontinued RCBS mould 57921 (50-450-FN). Apparently MBW uses quite a few discontinued moulds, one reason it can offer such a wide variety of cast bullets.

While waiting for that stuff to arrive, I broke down one of Dave Tobel’s handloads (the box was not labeled), finding a 435-grain cast bullet seated over a thin cardboard wad on top of 60 grains of coarse black powder. The empty, primed case was then “fired” in the rifle, both to see if it would go “bang” and to provide protection for the firing pin when checking the rifle’s trigger pull. On my Timney spring-gauge it averaged about 8 pounds but had a heavier take-up that almost (but not quite) functioned as the first stage in a two-stage trigger. The pull during the break was closer to 5 pounds.

The few remaining handloads were then taken to the range for the initial test-firing, which took place at 25 yards to see where the bullets landed with the military open sights. The group was centered several inches above the top of the triangular front post, which I had expected. Most iron-sighted military rifles were set up to shoot pretty high, even well into the twentieth-century, in order to hit a vertical target anywhere from close range out to where the average soldier could be expected to hit anything.

Some approximate numbers from a ballistic program indicated the bullets would land around 20 inches high at 100 yards. The rear flip-up sight could not be lowered, and the front sight was soldered directly to the barrel – unlike the blade sight on my 1884 .45-70, attached between two side posts with a small steel pin, which I had replaced with a taller blade for the same reason.

While at least one company offers a taller front sight for Springfield 1861 muzzleloaders and .50-70 trapdoors, I did not want to remove and replace the original. The barrel extended 1.2 inches in front of the sight, so one immediate thought involved clamping something behind the muzzle. While looking through a bunch of “gun stuff” I came across a barrel-band sling swivel stud that attached like a ring-clamp by tightening a screw. It was a little too small in diameter, but some judicious bending solved the problem, leaving some screw length between the stud halves.

The screw led to the idea of using a steel nut, threaded for the screw, as a front sight. My tackle box full of screws, bolts and nuts contained a square nut with the correct threading and was just about the right height. I filed one side until the nut just barely fit on top of the muzzle, and turning the screw allowed for a little windage adjustment. This proved to be really easy to aim, partly because the sight was so far away, due to the long barrel, that it looked pretty darn sharp even to my 60-something aiming eye.

The first group fired with my initial handload, the 450-grain Montana Bullet Works 450-grain FN and 70.0 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg, landed slightly above the top of the nut-sight at 25 yards. The muzzle velocity, however, was around 1,325 fps, a little faster than the original military load. Some calculating suggested 65.0 grains would result in the “correct” velocity. It did, and point of impact also dropped to right at the top of the front sight at 25 yards, three shots going into 1.38 inches, the first in the center of the square aiming point I had drawn on the target, and the next moving to the right as the barrel fouled.

After that I started shooting at 100 yards and also started brushing out the barrel fouling between shots, and the load grouped three shots into less than 3 inches. This may not sound like much to a twentieth-first-century rifle loony but is not bad for a black-powder cartridge rifle over a century-and-a-half old with open sights not designed for target shooting.

Next up were a couple of less traditional loads, also using the 450-grain flatnose. First, I tried 37.0 grains of Blackhorn 209, since the Western Powders data listed that load with a 475-grain cast bullet. This produced just about the same velocity as the 65-grain Swiss load, and landed in the same place at 100 yards, about 3 inches below the top of the nut post front sight.

Finally, I tried 10.5 grains of Trail Boss, which basically filled the case to the base of the bullet. Muzzle velocity was only about 900 fps, and the bullets landed 7 inches below the Swiss and Blackhorn loads, though with similar accuracy and a LOT less recoil. My rifle weighs 9 pounds, 2 ounces, and while full-power recoil is certainly tolerable even with the relatively small steel buttplate, the Trail Boss load is downright pleasant.

The next question, of course, was what to use the rifle for, aside from punching holes in paper and plywood. About that time the Montana hunting-season applications were due, and I applied for a bison tag for probably the twentieth time. The odds of drawing are less than one percent, even if you add the cow-calf option, and of course I did not draw. (My hunting luck is pretty good, but not my tag- drawing luck.) I had taken a bull on a ranch hunt in Wyoming in 1998, but it might be time to do another ranch hunt. Historical evidence indicates a .50-70 trapdoor would definitely work.

.jpg)