Down Range

Rifle Readiness

column By: Mike Venturino | January, 17

If a rifle is going to have a purpose – hunting, defense or competition – it needs to be ready before the first shot is fired. (That’s as opposed to a wall-hanger or item for a collection.) Readiness doesn’t mean only having proven itself capable of decent groups. Whether scoped or iron sighted, rifles must be zeroed properly, and it must feed and eject its correct ammunition. Much more importantly, the shooter needs to be proficient with it.

The American shooter’s excessive focus on groups is one of the biggest fallacies in rifle shooting. Certainly the rifle must put the shooter’s chosen ammunition into reasonable clusters. Afterward, groups mean nothing. Those are almost fighting words to some modern riflemen, but they are true. What counts is actually hitting a target.

It seems to me that the concept of “group” as the most important factor in rifle marksmanship arose from gun writers. In the beginning of firearms publications, editors and writers needed something to quantify their evaluations of rifles. They could write that said piece looked good and functioned properly, but was it “accurate?” Hence the “group concept” came about. The American Rifleman probably has handled the task better than any other magazine by shooting a test rifle using five, five-shot groups. Ever notice that such groups are seldom consistent from smallest to largest? That is a fact of shooting a string of groups; there will be a smallest and a largest and then some others in the middle.

Like every other gun writer of my era, I bought into the group concept and still do to a lesser degree. In fact, I am a darn good

group shooter from benchrest, but times change and so has my attitude. Nowadays I feel that when a rifle clusters bullets tightly enough for its shooting purpose, the bench shooting should be finished. The big-game hunter, varmint hunter, competitor or home defender must determine that criteria for his rifles.

No matter how precise a rifle might be, from muzzleloaders to those specialized for long-range competition, its inherent capability is useless if its sighting equipment is not zeroed. The purpose for the shooting dictates at what distance its zero should be set. For instance, a home defense rifle of some sort may not need zeroing for more than 50 feet. By contrast, my .222 Remington Magnum kept by the door for coyotes is zeroed for 100 yards. My BPCR hunting rifles were likewise set to hit dead on at 100 yards. When I hunted avidly with modern, bolt-action rifles, their scopes were adjusted for bullet impact about 2 to 3 inches high at 100 yards. Depending on exactly what caliber, bullet and velocity those rifles were firing, their zeros were somewhere between 200 and 300 yards.

Zero isn’t the only important factor. Another is where that rifle is going to put its first shot from a clean, cold barrel. In fact, many semiautomatic rifles tend to put their first shot significantly out of the group formed by following shots regardless of how many times it’s been fired. M1 Garands often do that, and recent shooting with a Ruger Mini-30 had shown the same tendency. The generally accepted theory for such semi-automatic behavior is that the first round is chambered by physically releasing the bolt, whereas the following rounds are chambered by the cartridge’s gas causing the mechanical operation of the bolt.

Aside from semiautomatic rifles, however, any other type of rifle can throw its first shot from a clean, cold barrel somewhere besides where it is aimed. Usually the errant bullet strays not far enough to matter, say at 100 yards, but it’s smart to check its placement at 200 or even 300 yards. (That’s as far as I can shoot at home to test matters.) I’ve been surprised to observe that with some rifles the first bullet will wander far enough to turn a killing shot into a wounding one at 300 yards.

Why would this happen? A cold barrel could throw the first shot, due to its own stress or a pressure point in its bedding, or for some other reason I cannot even fathom. A reason I do understand is caused by the compulsive gun-cleaning sort of guy who fills the barrel with solvent or oil after sighting in. That almost assures a flyer for its first shot in the field.

Then there is the matter of being proficient with the rifle. As said, I am a darn good shot from a sandbag rest when shooting groups – even to the point of winning a few bucks at it a time or two. Then came competitions and the discovery that I wasn’t nearly as good a tack-driving rifle shooter when away from sandbags.

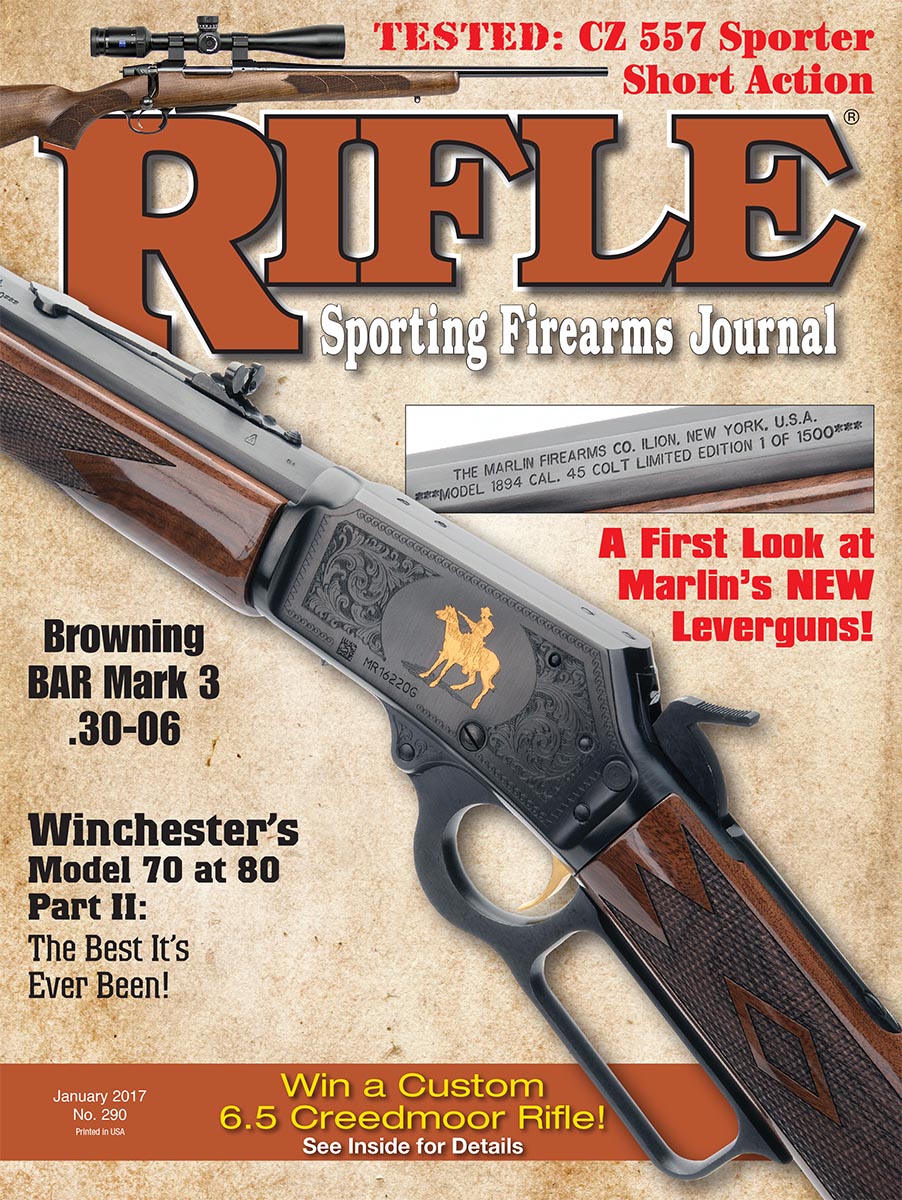

Here’s one way to observe a shooter’s level of rifle proficiency: Hand them a bolt action or levergun and tell them to shoot three shots offhand. Neophytes will lower the rifle from their shoulders while they operate the bolt or lever. Experienced shooters will not. Yvonne learned to keep her levergun shouldered all by herself during the years we shot cowboy action events. Every instructor teaching self-defense tactics with rifles tells students to keep theirs shouldered and ready even when the threat is down or gone away.

Surprising to me have been the times that I’ve observed people experiencing no trouble loading and shooting their rifles but fiddle-fumble around unloading it. In fact, I think it’s a good bet more people have accidental discharges during unloading than at any other time while using rifles.

For a shooter, bringing himself and his rifle to complete readiness is not a one-time affair. It’s a cumulative effort needing time and experience.