An American tradition has been that rifles adopted by our armed forces also become enormously popular with civilians. Not so much anymore. The change began with the 1957 adoption of the M14 chambered for the 7.62mm NATO. Because all M14 receivers were built with select-fire potential, they could not be sold as surplus to civilians after they were dropped from military service. Comparatively, hundreds of thousands Model 1903 Springfields, M1 Garands and M1 .30 Carbines were sold at bargain basement prices in the twentieth-century. (I got one of those surplus M1 .30 Carbines for my 16th birthday.)

Although the official service life of M14s was one of the shortest in U.S. military history, it coincided with a time when the draft was in place. Therefore, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of young Americans were trained in its use. In the first years of the Vietnam War, front line U.S. soldiers and Marines carried their M14s into combat. By about 1967, infantry units had a full issue of M16s, although some designated troops still carried M14s on occasion. Many of those young servicemen who had been raised on wood and steel rifles, resented trading in their M14s for the (then) unconventional appearing synthetic, aluminum and steel M16s. Neither did many troops, raised on .30-caliber hunting rifles, trust its small 5.56mm cartridge.

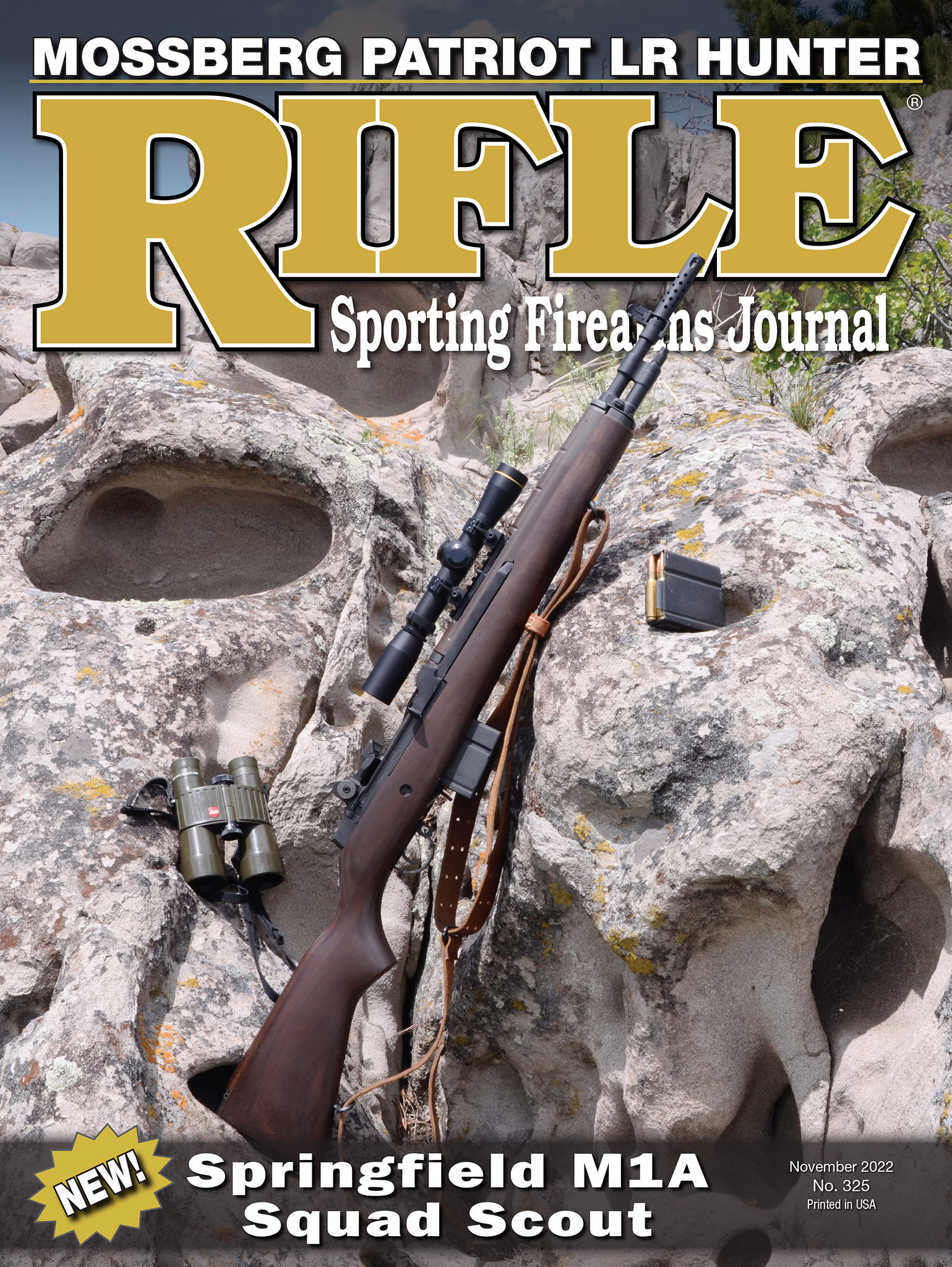

The M1A Squad Scout comes with a Picatinny rail atop the handguard. Mike mounted a Leupold Scout Scope on the barrel.

The government’s ban on releasing M14s to the shooting public created a market, especially with returned veterans. Production of M14s for the U.S. Armed Forces ceased in October 1963. According to the book

The Last Steel Warrior: U.S. M14 Rifle by Frank Iannamico, as early as 1971, a Texan named Elmer Balance perceived that there existed a demand for civilian legal, semiauto M14s. Millions of parts were left over by Springfield Armory’s, Winchester’s, Harrington & Richardson’s and TRW’s (Thompson, Ramo and Woolbridge) M14 production. With the original Springfield Armory closed down and turned into a museum, Balance was able to trademark the name. However the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATF) at that time would not allow him to use M14 for his rifle’s designation. He settled on M1A. By 1974, M1As were accepted for National Match Competition. Evidently, the BATF has since relaxed that attitude as several other companies have marketed replicas marked M14.

All M1As come with a flip-up steel buttplate under which is a compartment for cleaning items.

All Balance required for producing M14 facsimiles were receivers, which were investment cast by subcontractors. All other parts on early M1As were surplus from the above mentioned manufacturers. M1As cannot be termed identical to M14s, although in appearance it’s very difficult to discern one from other. Small engineering changes were made and of course, no provisions for select-fire were machined into the new receivers. M1As sold so well that within a few years surplus parts dried up. Newly-manufactured replacement parts became the norm.

The story of how Springfield Armory transitioned to its location in Geneseo, Illinois, is too long to delve into here. Suffice it to say that the company has become one of the most noted in the U.S. Besides M1A rifles, of which hundreds of thousands have now been made, Springfield Armory markets a wide variety of other rifles and pistols. (Past products I would like to encounter are M1As chambered for .243 Winchester and 7mm-08 Remington.) Currently, M1As are only chambered in .308 Winchester (aka 7.62x51mm NATO).

Let’s take a brief look at those two cartridges. Are they the same or not? According to Winchester’s white box offerings, they are the same. A fact that does need to be stressed is that Winchester’s .308 was introduced in 1952. Adoption of 7.62x51mm round by NATO wasn’t until 1954, after much debate among NATO allies who had their own ideas about cartridges. The U.S. bulldozed the other nations into adopting their development, but didn’t actually settle upon the M14 until 1957.

M1As come with this fully-adjustable rear peep sight.

American ordnance officers were stuck on .30 caliber (.300-inch bore, .308-inch grooves) due to the great success of the .30-06. New propellants allowed .30-06 ballistics with 150-grain bullets in a case .479 inch shorter (63mm to 51mm or 2.494 to 2.015 inches). Case head remained the same but case neck length was reduced from .385 inch to .303 inch and shoulder angle was made slightly sharper. Overall loaded cartridge length for 7.62x51mm NATO is 2.810 inches.

An interesting fact is that the ordnance people started testing with the old .300 Savage. Winchester was privy to the ongoing work and asked for and received permission to introduce the new round as its .308 Winchester prior to the U.S. Government adopting it. (My .308 Winchester Model 70 Featherweight must have been one of the first as its serial number dates it from 1952.)

Mike’s .308 Winchester handloads for the Squad Scout carried these four types of bullets.

According to the Iannamico’s book, among many types of special purpose American 7.62mm NATO loads, standards were M59 with 150-grain steel core bullet rated at 2,750 feet per second (fps) and the M80 with 146-grain lead core bullet at the same basic velocity. Other NATO countries had their own loads that did not differ greatly from America’s. Even countries not involved in NATO adopted the round. Most used it in one version or another FN-FAL.

My personal introduction to Springfield Armory’s M1A came in the late 1970s by way of a Vietnam combat veteran who took me under his wing in regard to learning how to hunt Montana big game. He had trained in 1967 on the M14 and greatly admired and respected it. Years after returning from that war, he bought the first M1A encountered. Upon seeing it, I asked him about hunting with it. He replied, “I don’t. My family has a cabin on 160 acres a stone’s throw from the Yellowstone Park north boundary. Bears are common up there, so a powerful semiauto like this rifle is a comfort to have close by when I’m working there.”

Mike test-fired the M1A Squad Scout with these three factory loads.

Over the decades I’ve owned several M1As, either purchased new or used. They were all Springfield Armory Standard Models with 22-inch barrels, walnut stocks wearing the usual fully-adjustable rear sights with .069-inch apertures and blade front sights of .062-inch width, set inside protective wings. The weight is listed at 9 pounds, 3 ounces. The rifling twist rate for all was one turn in 11 inches. Never was a problem encountered with any of my previous M1As in regard to functioning, but as I aged, shooting with iron sights became problematic. That’s why my most recent M1A Standard Model was sold a few years back.

When asked if I might be interested in trying Springfield Armory’s Squad Scout M1A, definitely I was, because it comes with a Picatinny rail atop its synthetic handguard. Especially so, considering there was a Leupold 1-4X Scout Scope just sitting here with no rifle for it. One was ordered; specifying walnut stock, although a less expensive, black synthetic-stocked version is cataloged weighing 9 ounces less. (I stuck with a wood stock because I believed it likely that the Squad Sniper would be a fine shooter and I’d end up buying it, which I did.) Interestingly, the 18-inch barreled Squad Scout M1A weighs the same 9 pounds, 3 ounces as Standard Models with 22-inch barrels. That I attribute to the former version’s steel muzzle brake and Picatinny rail. The overall length is 40.5 inches. With a Leupold scope, mounts, unloaded 10-round magazine and leather sling, it weighs 10.5 pounds.

Safeties are a sliding lever that sets in the trigger guard. Pushed back, the rifle is on safe. Pushed forward, it is ready to fire.

All M1As come with sling swivels, flip-up buttplates with storage for cleaning equipment, pistol grip stock configuration and are shipped with 10-round magazines. The length of pull is 13.25 inches while the finish is black Parkerizing and oiled wood.

An interesting fact learned from Iannamico’s book is that prior to the 1986 change in federal law, full-auto Springfield Armory M1As could be special ordered as select fire, with of course, the buyer fulfilling all BATF rules. He also stated that few were sold and so they are very rare. Having had the opportunity to briefly fire an original, select-fire, legally owned M14, I found muzzle climb in full-auto virtually impossible to control.

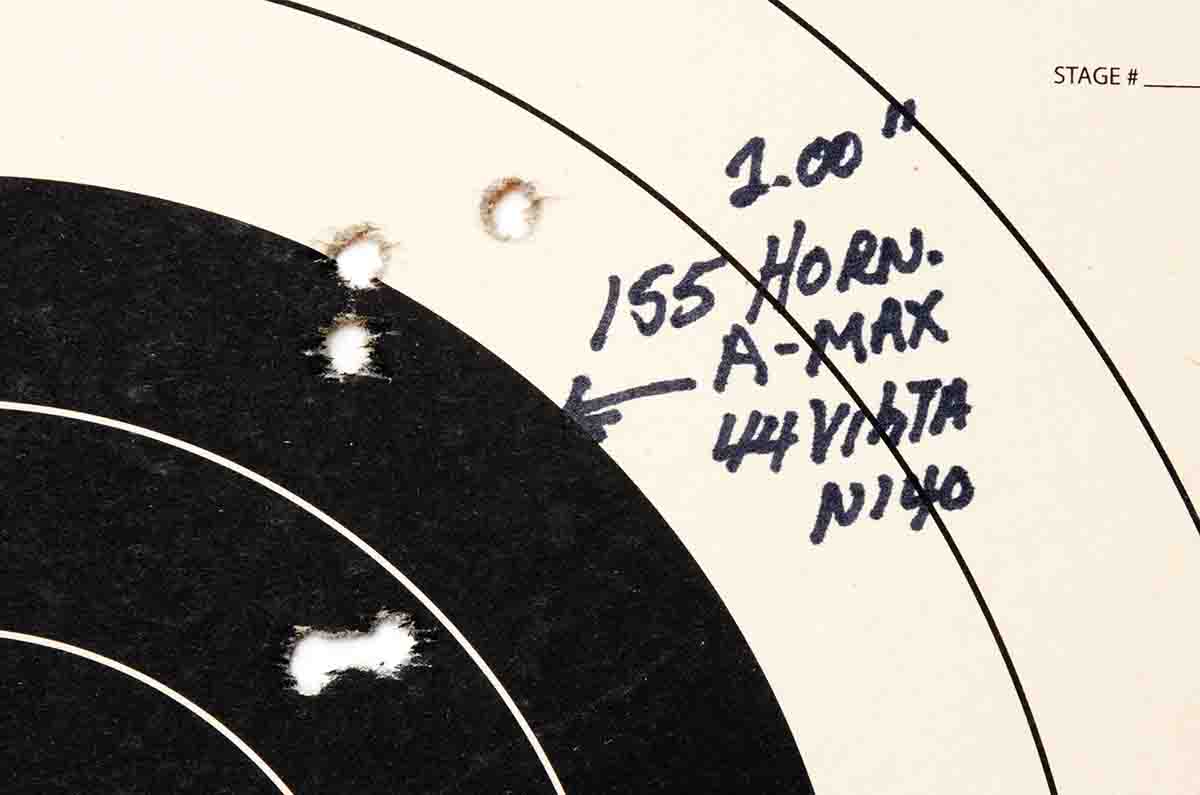

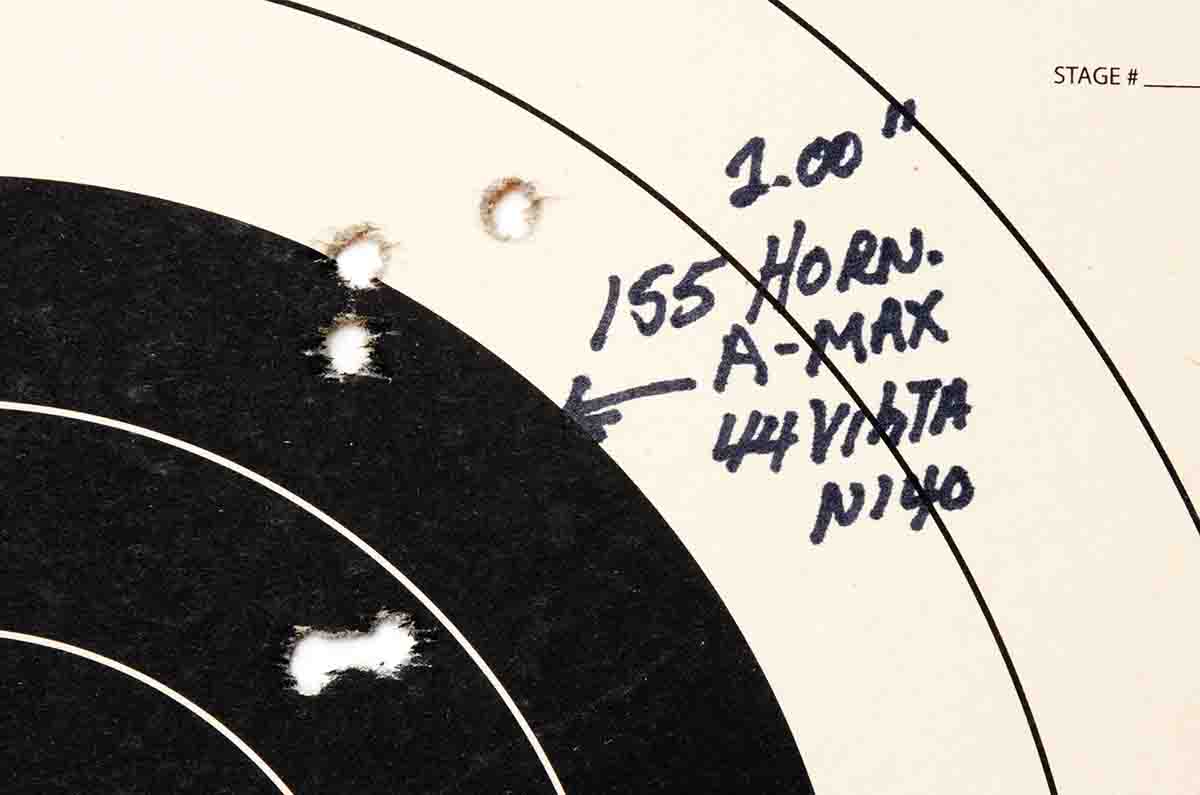

That brings us to the shooting capabilities of this Squad Scout M1A. Five-shot groups fired at 100 yards ranged from excellent to no better than usual with iron sights. The mediocre groups surprised me because they all came with factory loads carrying 150- to 155-grain bullets or handloads with same. The smallest with those bullets was 2 inches the largest were above 3 inches. By my thinking, the 11-inch rifling twist rate should handle 150/155-grain bullets and have done so with my past M1As. Conversely, many groups fired with Sierra 168-grain and Hornady match bullets were very good. Several handloads and the Nosler factory load with 165-grain AccuBond were barely over MOA at 100 yards.

The M1A Squad Scout has an 18-inch barrel fitted with muzzle brake.

Some years back, a semiauto .308/7.62mm rifle of another make was encountered that gave “sticky” chambering with cases sized in ordinary full-length sizing dies. What happened was that the force of the bolt did fully chamber those rounds, but the only way to unchamber them was to fire the rifle. An RCBS small base .308 sizing die was acquired and the sticky case problem disappeared. It’s been used for all my .308/7.62mm case resizing since.

A perusal of several reloading manuals shared one interesting fact. It seemed than none use the official 2.810-inch overall cartridge length of 7.62mm NATO. The Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading 8th Edition has a special “service rifle” .308 Winchester section. It lists 2.800 inches for bullets from 155- to 178-grain HPBTs. The Lyman 50th Edition Reloading Handbook gave maximum overall loaded length (OAL) of 2.800 inches down to 2.775 inches. When I’m working with bolt-action .308s, seldom do I pay much attention to OAL, but with these detachable box magazines, it is a critical factor.

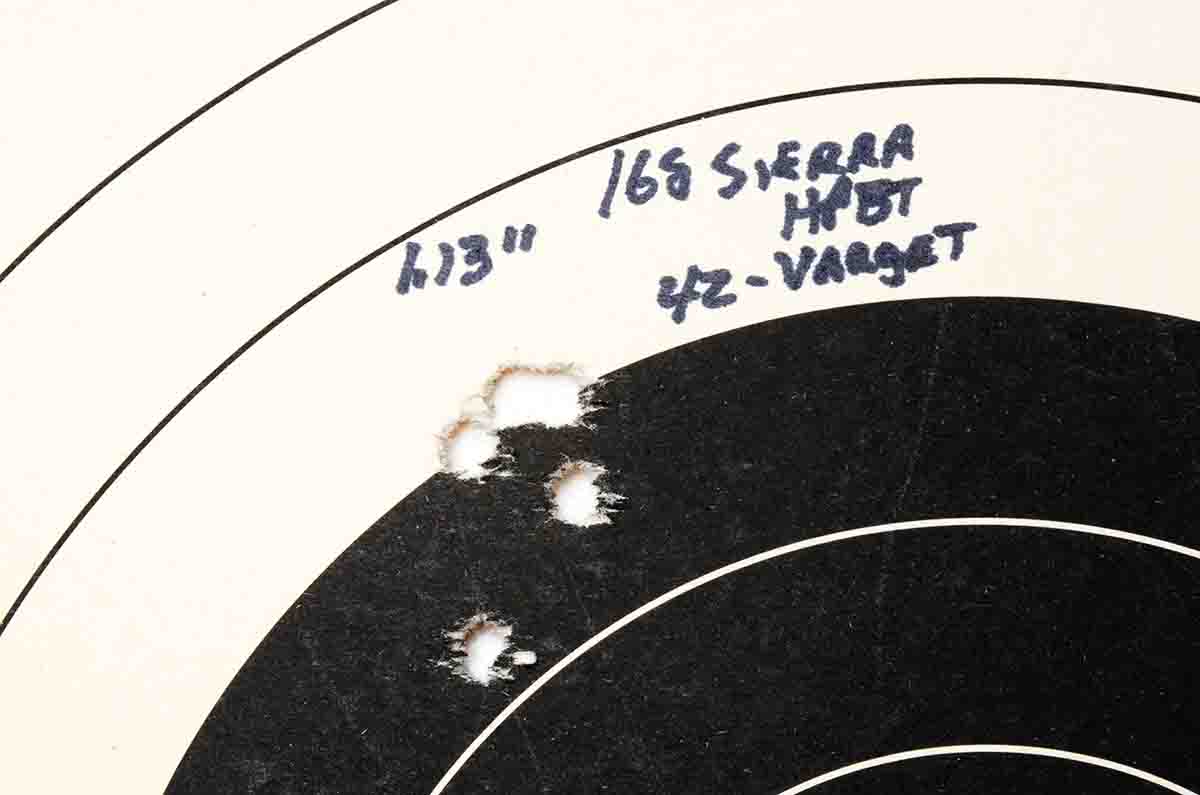

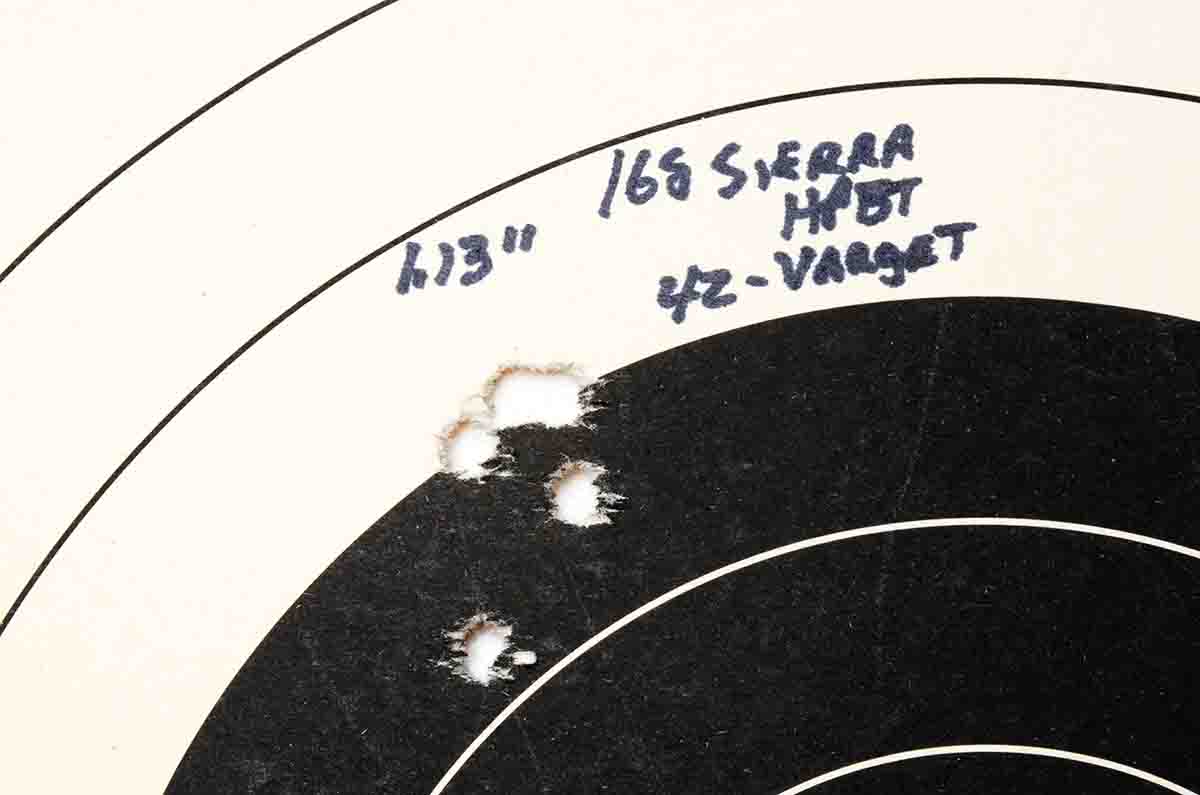

This group was typical of most loads fired with 165- to 168-grain bullets.

Picking suitable propellants for .308/7.62mm can also cause a handloader to pause. That’s because there are so many to choose from. For instance, in the above mentioned Lyman book, there are up to 16 powders listed for some bullets. They range from IMR-3031 on the fast side to IMR-4350 on the slow end. In Hornady’s Service Rifle .308 Winchester section, there are 11 propellants listed for each bullet. My favorite .308 Winchester propellant since 1978 has been IMR-3031, mostly for handloads used in a variety of bolt actions. However, for this Squad Scout M1A, powders with which I’ve had less .308 experience were chosen. Three factory loads were also fired.

This group was the best one fired with 150- to 155-grain bullets.

Some notes from my last M1A Standard Model’s chronographing were on hand, which allowed for comparison of 22-inch barrel velocities with this one’s 4-inch shorter barrel. Some of Nosler’s 165-grain AccuBond factory loads in the Standard Model 22-inch barreled M1A had gotten 2,707 fps. This Squad Scout rifle gave 2,565 fps. Since this particular M1A is mine now, I foresee it getting plenty of one specific load combination. That is the mix of 168-grain Hornady HPBT bullets over 45.5 grains of Vihtavuori N150 in Winchester brass with Winchester Large Rifle primers. So far, in the firing of about 150 rounds, there has been no failure to function with ammunition ranging from military surplus rounds to a dozen factory loads and handloads.

Springfield Armory’s M1As are shipped with 10-round magazines (right) but can also use M14 20-round magazines (left).

Its customary for a writer to include something about a reviewed rifle that they did not like. My only one is that the Parkerizing on the supplied 10-round magazine was thick to the point the magazine required a smart slap to seat properly. A much worn 10-round magazine left from previous M1As seated easier.

While not a realistic candidate for big-game sporting purposes, I see M1A Squad Scouts as nigh on perfect for ranchers and farmers who need to protect stock from large predators. Also, it would be perfect for Texans needing to thin out feral hogs devastating their property.

.jpg)