Triumph and Tragedy

The Indelible Mark of Alexander Henry

feature By: Terry Wieland | May, 18

Any list of the great British riflemakers of the nineteenth century must include Alexander Henry of Edinburgh. The list of Henry’s accomplishments just seems to go on and on, yet to all intents and purposes, his business died with him. Today, 125 years after his death, the name “Henry” lurks at the fringes of rifle history, with no single great accomplishment to lend immortality.

From a standing start of nothing, Henry created a gun business, became wealthy on the quality of his rifles and the value of his inventions, and was awarded royal warrants from the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) as well as monarchs all over Europe. Alexander Henry was commissioned by Queen Victoria to build a double rifle for presentation to her gamekeeper at Balmoral, John Brown – a signal honor, given the fact that James Purdey held the Queen’s own royal warrant.

Henry also achieved considerable renown as a local councillor and officer of the volunteer movement of the 1860s, when rifle shooting became a popular and widespread activity. He was involved from the beginning with the National Rifle Association (NRA), set up in 1859 (12 years before its American counterpart) to promote skill with a rifle among civilians. Henry’s rifles were prominent in the winners’ lists.

Yet, Henry was also pursued by misfortune and even tragedy. His eldest son was killed in a shooting accident at the age of 12, shot in the head by Henry himself (through no fault of Henry’s). Two other sons proved to be little better than ne’er-do-wells who frittered away their inheritance. Henry lost money in an infamous fraud case. Finally – and most famously – he lost a lawsuit against John Farquharson over patents for the single-shot rifle action that became the most successful in Britain and inspired the Ruger No. 1.

Throughout all this, Henry persevered and continued to add one accomplishment after another until the day he died. He was a man to be admired.

Compared with some other British gunmakers, such as James Purdey or Henry Holland, Alexander Henry has always been a bit mysterious. It was widely believed that no photograph of him existed, and there were gaps in his biography.

Dallas has now published Alexander Henry, Rifle Maker. Written in cooperation with Henry’s great-great-grandson, the book not only casts light on previously unknown parts of his life, the authors also managed to unearth three images of Alexander Henry, including a photograph.

More valuable than simply the facts, however, are Dallas’ assessment and conclusions about, particularly, the infamous Henry-Farquharson lawsuit and its aftermath. No one today knows as much about how the English gun trade operated, to say nothing of the patent office, as Donald Dallas. In a court case, he would be an unassailable expert witness. In his opinion, to be blunt, Alexander Henry was robbed.

Alexander Henry’s life’s work began almost at birth. He was born in 1818 and grew up close to the Royal Horse Artillery based at Leith Fort, on the east coast of Scotland. His father was a wheelwright at the base, and Alexander was fascinated by ballistics. At the age of 12, he was apprenticed to Thomas Mortimer, the well-known gunmaker, and from an early age showed a remarkable aptitude for his chosen trade. At the age of 17, he constructed a complete rifle from forgings, using tools he made himself, and became Mortimer’s manager when he was just 22. Henry stayed with Mortimer for 22 years.

As manager, he oversaw construction of Mortimer’s exhibits in the Great Exhibition of London in 1851, which included a double-barreled fowling piece, a double rifle and a pair of silver-mounted Highland pistols, for which Mortimer was awarded a gold medal. A year later, at the age of 34, Henry struck out on his own. He purchased the gunmaking business of Samuel Gourlay, took over his numbers books and numbered his own guns from where Gourlay left off.

Throughout his professional career, Alexander Henry was diligent about numbering, using patent-use numbers on his barrels and other action parts as he licensed his patents (especially barrels and rifling), and even provided rifles for other makers to finish as their own. This was a common – and quite acceptable – practice among Britain’s best gunmakers, and Henry himself did the reverse.

Henry went on his own just as the transition began from percussion to breechloading systems. While at Mortimer’s, he had shown a particular aptitude for rifles, and rifling patterns became his specialty. This, too, was fortuitous, because the search was beginning for a new British military rifle which led, with many twists and turns, through the adoption of the Enfield Pattern 1853 muzzleloader, the Snider-Enfield conversion and, finally, the Martini-Henry. Alexander Henry played a prominent role in all three.

A little-known contribution by Alexander Henry was the design of the rifling used in the 1853 Enfield, which of course continued with the Snider. As rifles came into general military use, there was a widespread search for methods of making them more accurate. One approach was a grooved barrel firing a belted ball, with the belt fitting the grooves. The Brunswick rifle used this method, and both John Dickson of Edinburgh and James Purdey of London produced such rifles to their own pattern. Alexander Henry hit on the idea of three-groove rifling and a bullet with three fins that would match the grooves. This then evolved into the concept of three-groove rifling and a bullet of soft lead which would expand on firing to grip the rifling.

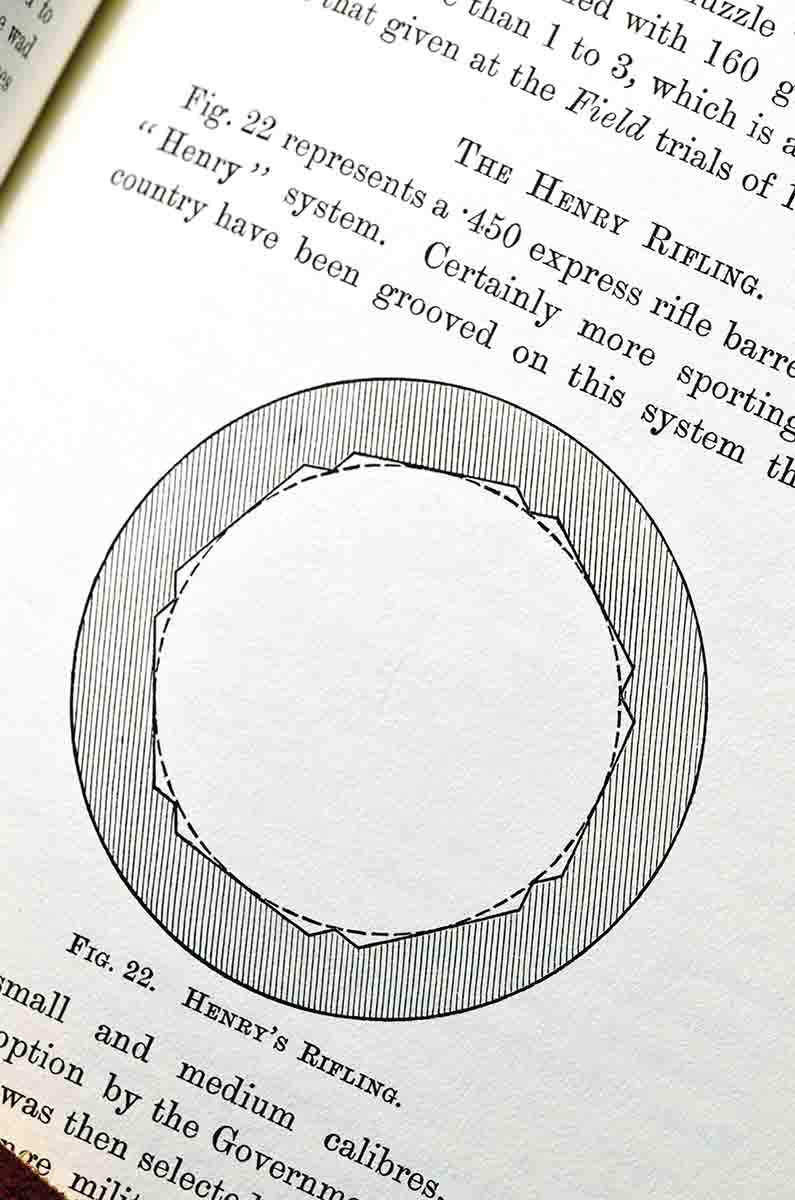

Alexander Henry pursued his idea further and in 1860 filed the patent that would make his name. Henry-style rifling employed a system of lands and grooves (see illustration) that would allow the expanding bullet to grip it easily, yet plug the bore against gas leaks, and be easy to clean. It was originally intended for muzzleloaders but proved to be easy to adapt to breechloaders as they came into use. Henry further refined his system by making the rifling deeper at the breech but becoming gradually shallower as it approached the muzzle. This ensured a firm grip on the bullet and a good gas seal.

In 1863, his employee (and future business manager and son-in-law) Alexander Brown fired a 20-shot group at 900 yards that measured 10.5 inches – phenomenal performance for that (or any) day, and one that Henry exploited in advertising.

The explosion of the Volunteer Movement, with its continuing demand for rifles, combined with Alexander Henry’s growing reputation, ensured steady sales. In 1865, when the War Office announced a competition for a breechloading rifle to replace the stop-gap Snider-Enfield conversion, Alexander Henry naturally entered it. The process dragged out for six years, and it was not until 1871 that a winner was announced: The British Army would adopt the Peabody-Martini action with a barrel using Henry rifling and the new rifle to be known as the Martini-Henry.

Henry had entered a single-shot falling-block rifle of his own design, but it had nagging problems with its extractor. What’s more, it required two motions in reloading; one to close the breech and a second to cock it. Since the Martini action closed and cocked with one motion of its lever, it was much faster, and Henry himself agreed that the small-arms committee had made the right decision. His name, however, was now firmly attached to a weapon that would go down in history, most famously at the defense of Rorke’s Drift in 1879, during the Zulu Wars.

The cartridge worked well in Henry’s own falling-block action, but not in the Martini. Accordingly, William Eley (Eley Brothers) went to work designing a .450 based on the old .577 Snider case elongated but necked down into a bottleneck. It was almost an inch shorter than Henry’s .450 straight case and worked well in the Martini-Henry, but it could easily accommodate the mandated 85 grains of black powder to propel its 480-grain bullet.

At this point, Alexander Henry decided to design his own hammerless, self-cocking, single-shot action. It was to be a falling block with an underlever. It was here that Henry ran afoul of John Farquharson. Farquharson was a fine rifleman but an undeniable rogue who made his living ostensibly as a gamekeeper and had spent time in jail for poaching. Henry did not trust him, and banned him from his workshops.

Those were the facts before the court. The situation previous to this, however, and more particularly what happened afterward, suggest that Alexander Henry was robbed. First, patent applications were an expensive process, and Farquharson was not a man of means. Second, he was a good rifleman, but he was neither an engineer nor a gunmaker and had never previously designed anything mechanical.

After the case was settled, George Gibbs of Bristol, a prominent riflemaker, and his colleague, rifling designer William Metford, took control of the Farquharson action and began producing the Gibbs-Farquharson-Metford long-range rifle, one of the finest target rifles of all time. Indications are that Gibbs and Metford financed both the patent application and the legal battle for just this purpose. Whether that makes them complicit in the theft, who can say?

Although Alexander Henry went on to design alternative hammerless, single-shot actions, none was particularly successful. In all, only 90 Henry hammerless rifles were produced, compared with 2,522 hammer rifles.

In 1883, The Field conducted its famous rifle trials in London, but some prominent riflemakers did not participate, including Alexander Henry. Holland & Holland swept the field, and in one fell swoop cemented its reputation as England’s foremost riflemaker. Henry was busy at the time with extensive exhibitions in Calcutta, and presumably just did not have the time.

Henry did not have a great deal of time to rue this mistake. He died, a wealthy man in 1894 at the age of 76. Unfortunately, his two remaining sons, John and Alick, did not take after their father and his business, reorganized as Alexander Henry & Co. and folded soon after. Today, the name is owned by his former arch-competitor John Dickson, along with Thomas Mortimer (where Henry started out) and Daniel Fraser (a Henry-trained riflemaker and later competitor).