Walnut Hill

Fantasy Land, Farewell

column By: Terry Wieland | May, 22

Think of the Minié ball, smokeless powder, the bolt-action rifle, and jacketed bullets, to name just four.

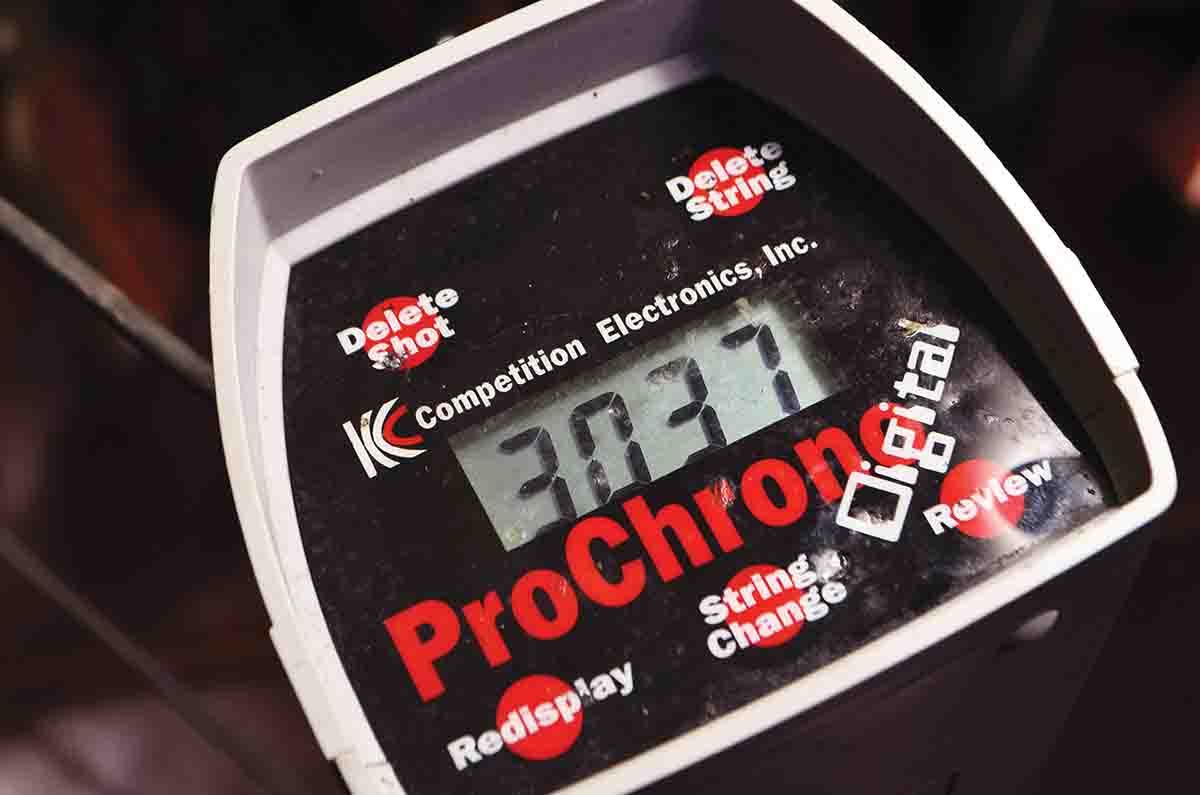

To that list I would add, roughly 30 years ago, the Shooting Chrony. The Chrony was not the first chronograph available to the average guy. Ken Oehler’s sophisticated machines were around years before that, but while we all wanted one, most of us could not afford it.

The Chrony was different. At a mere $90, give or take a shekel, anyone who could afford to shoot could afford a Chrony, and the whole thing was compact and light enough to stick in your range bag, whereas the Oehlers required benches, cables and tripods to hold the screens and so on. I should add that, after my first Chrony, I later acquired an Oehler 35, which gave me printouts, averages, extreme spreads and much more, and I used it for the next 15 years.

The Chrony did none of that. It provided you the velocity one shot at a time, memorized nothing, averaged nothing, and a shooter had to be able to read the screen from a distance or walk out in front of the shooting line. By today’s standards, it was primitive in the extreme. Still, it was the Chrony that made the difference. Not only did it give shooters vital information most never had before, it pushed a host of other manufacturers to come up with something comparable in practicality and price.

Why was this a turning point? Because, suddenly, both for handloaders and serious riflemen, everything changed. On the one hand, when some loudmouth showed up at the club claiming to have created a handload or a wildcat cartridge that was faster than the Swift and more powerful than the Lott, shooters could demand to see proof. Things quieted down considerably.

The president of my SCI chapter back in the 1980s was a guy who claimed to be the final word on all things rifle, and truth to tell, he was pretty knowledgeable. He was also, however, insufferably annoying. As I recall, he claimed to have some arcane formula for calculating velocity based on felt recoil, and while we could all roll our eyes, we couldn’t prove him wrong. As soon as our first member got his hands on a Chrony, that ended that.

More productively, handloaders could see exactly what they were getting out of a rifle instead of depending on figures in the handloading manuals and hoping for the best. Of course, it could also be sadly disillusioning.

In 1975, I bought my first high- quality rifle – a Weatherby Mark V, one of the last made in Germany by J.P. Sauer, chambered for the .300 Weatherby. That was, and is, a magnificent cartridge and it was certainly a lucky rifle. With it, I killed two caribou in northern Quebec, an Alaskan brown bear and a moose high in the Laurier Pass of British Columbia, Canada. Three of the four involved some lucky shooting, and the moose was one of the most spectacular shots I’ve ever made. The bull was running on the far side of a ravine. I didn’t know the range, except it was a long way, so I held about two feet high and three in front (That’s my recollection, anyway.) and knocked the bull off its feet with a spine shot.

My ammunition was handloaded 200-grain original Trophy Bonded Bear Claws ahead of a shovelful of Hodgdon H-1000. I can’t say precisely how much powder because it exceeds Hodgdon’s maximum listed load, but that’s not the important thing anyway. I thought I was getting close to 3,000 feet per second (fps). When I got my Chrony and fired a couple of shots across its bow, I found I was getting barely 2,800. The catch was that my rifle had a 24-inch barrel, and published velocities with the .300 Weatherby in those days were measured with a 26-inch barrel.

Interestingly, Hodgdon’s listing today is 85 grains maximum with a 200-grain bullet, at 2,963 fps, and its test barrel is only 24 inches. Why? I have no idea. Anyway, the point is that the Chrony showed me I was getting a lot less than I thought I was. Measuring a few more loads shook my confidence in that rifle in spite of its stellar record of lucky shots, and I never hunted with it again.

Interestingly, shortly after the Chrony made its appearance, 24-inch barrels for magnum cartridges disappeared from the Weatherby catalog. Nothing to do with me, but I assume a lot of Weatherby owners bought Chronys, and also found that the emperor was scantily clad.

In the 1990s, when I’d started writing for some serious gun magazines, I got my Oehler 35 and became religious – some would say obsessive – about chronographing every load I put together.

One little project, carried out around 2002, was prompted by that earlier revelation on barrel length. I’d always read that you lose about 25 fps for every inch of barrel you cut off. In the case of the Weatherby, losing two inches of barrel should have reduced velocity from, say, 2,900 fps to 2,850.

Many factors go into this, such as bullet weight and the burning rate of the powder, but I thought it would be an interesting experiment just the same. I took a mutilated Enfield P-17 with its 26-inch barrel and a Swedish Mauser with a 28-inch barrel, constructed a vast number of identical loads and started cutting the barrels off an inch at a time. Both ended up, as I recall, at 16 inches. (I’m going from memory here, since all the records got lost somewhere along the line, including the magazine in which the results were published.)

I confirmed a couple of suspicions: Reducing from 26 to 25 inches matters less than reducing from 18 to 17. It’s a matter of percentage. Also, the slower the powder, the more those short-barrel inches count.

I was averaging five shots at each barrel length, and of course, once the barrel had been cut, there was no going back. I had two loads for each rifle – one using a light bullet and fast powder and the other a heavy bullet and slow powder. The whole operation took the better part of a morning; fortunately, it was cool, so barrel heating did not enter into it.

Looking back, there are some things I wish I could have done, such as trying the same bullet with different powders, or different bullets with the same powder, but one can go on and on fantasizing about what could be done given unlimited time and resources.

One thing sticks out very clearly in my mind. The velocity loss per inch varied widely, from length to length, rifle to rifle and load to load. I compiled averages for each load, for each rifle and so on, then made an overall average for each rifle, then combined them to give me an overall super-average for the whole operation, and guess what?

That average worked out almost exactly to 25 fps per inch.

Now, readers could argue that I went to all that work, and destroyed two rifles into the bargain, all to prove something that I had read for years. However, I also proved that in any given situation, with any load and rifle, the average almost certainly would not work. As rules of thumb go, this one could be summed up as “shorten the barrel, reduce the velocity.” But then, we already knew that. As one of the toilers in the gunpowder and loading-manual business used to say, “Aaaaaah, ballistics!”