World War II Semiautomatics

Reviewing a Trio of Venerable Rifles

feature By: Mike Venturino | May, 17

A study of World War II shows that the vast majority of all infantry troops were armed with bolt-action rifles designed prior to, or slightly after, the turn of the twentieth century. Examples of such were U.S. ’03 Springfields, German K98k Mausers, British No. 3 Enfields, Soviet Mosin-Nagant ’91/30s and so forth. Only three semiautomatic long guns were issued in significant numbers for ground combat – one each by the U.S., Germany and the Soviet Union: the M1 Garand, 4,000,000; G/K43, 400,000 to 500,000; and SVT40, about 2,000,000, respectively. Sources vary on these figures.

Be sure that “significant numbers” is not confused with “no other.” For instance, Germany put out a few thousand G41s for trials on the Eastern Front, Japan tried to copy our M1 Garand, and U.S. ParaMarines at first were given M1941 Johnsons. The Soviets fielded a number of SVT38s before altering it to the much more common SVT40. The little U.S. M1 .30 Carbine semiautomatic should not be forgotten, even though it wasn’t considered a standard shoulder arm for infantry troops. None of the three semiautomatics adopted by major nations were chambered for new cartridges, i.e., .30-06 (U.S.), 8x57mm Mauser (Germany) and 7.62x54mm R (Soviet Union).

America’s M1 Garand came first and perhaps deserves an award for taking longest to travel from drawing board to battlefield. John C. Garand started work on it at the government-owned Springfield Armory, circa 1923. His design for America’s first semiautomatic military rifle wasn’t adopted until 1936. Then chief of staff for the U.S. Army, Douglas MacArthur had something to do with the delay. At first, Mr. Garand built the soon-to-be M1 for an experimental .276 cartridge. Although it would likely have served well as a military round, General MacArthur nixed it with sound reasoning. Besides having millions of .30-06s left over from World War I, American Browning Models 1917 and 1919 machine guns were all chambered for .30-06, as were BARs (Browning Automatic Rifles). Re-equipping with new versions of all those weapons would have been prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

So Garand returned to the drawing board and revised his basic design to accommodate a larger cartridge. It passed all tests and was accepted as the M1 (Model One) in 1936. In its early form, the M1 was termed a “gas trap” design. It functioned by an appendage at the end of the barrel trapping gas as it exited the muzzle and using it to cycle a piston located beneath the barrel. By 1940 this method of trapping gas was considered less than perfect. So a hole was bored at the bottom of the barrel to siphon propellant gases for cycling the mechanism. Most gas trap M1s were recalled and converted at Springfield Armory to the revised method.

M1s were rather large rifles, thick in their middles, because the eight-round en-bloc loaders held cartridges in staggered rows. Barrel length was 24 inches. My two World War II vintage M1s – one each by Springfield Armory and Winchester Repeating Arms – weigh 101⁄2 pounds with slings. In addition to being semiautomatic in function, M1s were America’s first infantry rifles designed in this country to use peep rear sights for all shooting purposes. U.S. Model 1917s did have them, but it was a British design.

Regardless, the M1’s rear sight arguably was the best put on a battle rifle up to that point. It was properly located near the shooter’s eye and was fully adjustable for windage and elevation. Those fitted to World War II Garands have come to be called “locking bar” sights by collectors. In operation, the “bar” on the sight’s right side is rotated counterclockwise two clicks to free the sight for adjustment. Once the peep is located where the shooter needs it, the bar is then rotated clockwise to “lock” it in place. The M1 Garand’s front sight also deserves a mention. It is a simple post, but in an era when close combat with bayonets was a definite possibility, it was wisely fitted with protective wings on each side. That may have been a feature borrowed from the British, because U.S. infantry rifles prior to the Model 1917s did not have sight wings.

As wonderful as the legendary Garand is considered, it was not perfect. One small flaw was the en-bloc loader inserted from the top which, incidentally, ejected upward as its last round was fired. It precluded mounting a telescopic sight directly above the rifle’s bore, hence when a sniper version of the M1 (M1C and then M1D) was finally developed, the scope was offset to the

When initially adopted by the U.S. Army (1936) and U.S. Marine Corps (1941), the M1 was disliked by long-serving NCOs. It was said to be less accurate than the standby Model 1903 Springfield and more complicated to maintain. Both charges were true, but semiautomatic firepower trumped both charges. By target rifle standards, as-issued M1s did not group as tightly as ’03s. In combat that mattered little if at all. M1s were harder to maintain, but that was a function rectified by training. In my considerable reading of World War II oral histories, most mentions of M1 functional failures occurred with the black sand (volcanic ash) of Iwo Jima.

Only slightly behind the U.S. in developing a semiautomatic infantry rifle was the Soviet Union. In the mid-1960s, the inside back covers of various gun magazines were enjoyable due to their full-page ads selling various military surplus rifles. One that was especially attractive to teenage eyes was the exoticly appearing Soviet SVT40 (Samozaryadnaya Vintovka Tokareva 40), a “self-loading rifle” designed by Fyedo Vassilevich Tokarov and adopted by the Red Army in 1940. About 45 years passed before I added an SVT40 to my World War II collection, and it cost much more than those in 1960’s magazine ads.

Compared to M1 Garands, SVT40s were relatively light and slender, because their magazines were detachable boxes extending in front of the trigger guards. Barrel length was 25 inches with an overall length of 48 inches. Also compared to M1s, SVT40s had a few other benefits. Their 10-round magazines were loaded in the rifles by means of the same five-round stripper clips used in the Mosin-Nagant Model 91/30 bolt action. Usually a soldier was issued only two magazines: one in the rifle and a spare in his pack in case of damage to the first. Good scroungers likely loaded themselves up with more magazines. The SVT40’s gas operating systems also sat atop the barrel instead of beneath it, as with the M1. This allowed cursory cleaning simply by removing the handguard. In regard to being used in a sniper role, the SVT40 only needed small, half-round milled cuts at the receiver’s rear for scope mounting directly over the rifle’s bore. The scope was the PU 3.5x. My iron-sighted SVT40 weighs 9 pounds. A scoped version weighs 10 pounds.

SVT40 iron sights were barrel-mounted, open rear types. They were elevation adjustable to 1,500 meters but had no provision for windage. Front sights were thick posts protected by sturdy hoods with openings at their tops to allow light in. Front sights could be drifted laterally for windage.

The factors that made SVT40s exotic looking and attractive to my teenage mind were ports in the wood handguard and a perforated protective steel cover extending ahead of the handguard. The barrel ended with a flash hider. The Red Army must have been preparing for intense firefights with these barrel cooling features. At one time the supposed intention of Russian generals was to equip their entire army with SVT40s. That did not happen. The German invasion caused them to rely primarily on bolt actions. Even though up to 2 million SVT40s were manufactured, mostly they were issued to NCOs and snipers. Some few thousand were also made in carbine form with 18-inch barrels, but American experts think most now in-country are fakes. A select-fire version was also made, the AVT40. Keeping one of those on target in full-automatic must have been exceedingly difficult considering the power and recoil of the 7.62x54mm.

Of first importance in writing about Germany’s semiautomatic infantry rifle is the G/K confusion. G stands for Gewehr, German for “rifle.” K stands for karabiner, the meaning of which is apparent. There were no differences in rifles. The G designation came first and K in 1944. (Evidently German ordnance officials liked to change rifle names.) Today many Internet experts consider the G/K43 an inferior design. I don’t agree. It was a good design hampered by poor raw materials and manufacturing processes.

Next in importance regarding the G/K43s is that for Germany, it was too little too late. As with American ordnance officials, Germany’s officials did not want a hole drilled in the barrel to bleed off gas for functioning. By the time that tiny hole in a rifle barrel became acceptable and approved for G43 full production, it was April 1943. Germany had by then already lost the war in practical terms. By the way, said hole was also in the top of the barrel, along with the gas system.

My sample is a K43. It has a 22-inch barrel and weighs 10 pounds without a scope and 111⁄2 with. That’s one benefit of the design. All were built with a scope rail on the action’s right side. Scopes were the ZF4 (4x), and mounts were developed specifically for this rail. The entire scope/mount assembly can be removed in seconds. Metallic sights consisted of a barrel-mounted open rear adjustable to 1,200 meters. The front was a simple post dovetailed so a windage zero could be obtained. Interestingly, no provision was made for mounting bayonets. As with the SVT40, Germany’s primary semiautomatic had a detachable 10-round box magazine. Doctrine called for its loading by means of five-round stripper clips, but likely landsers (infantrymen) issued G/K43s gathered all the extra magazines they could find.

Although developed and made by the Walther firm, production also occurred in the Gustloff-Werke factory and in the Berlin-Lubecker Maschinenfabriken facility. Mine came from the latter, the only one of three manufacturers to use a synthetic material, Durofol, for handguards. Contrary to prewar and early-war German weapons’ finishes, G/K43s look pitiful. The war was going badly and no effort was wasted on cosmetics.

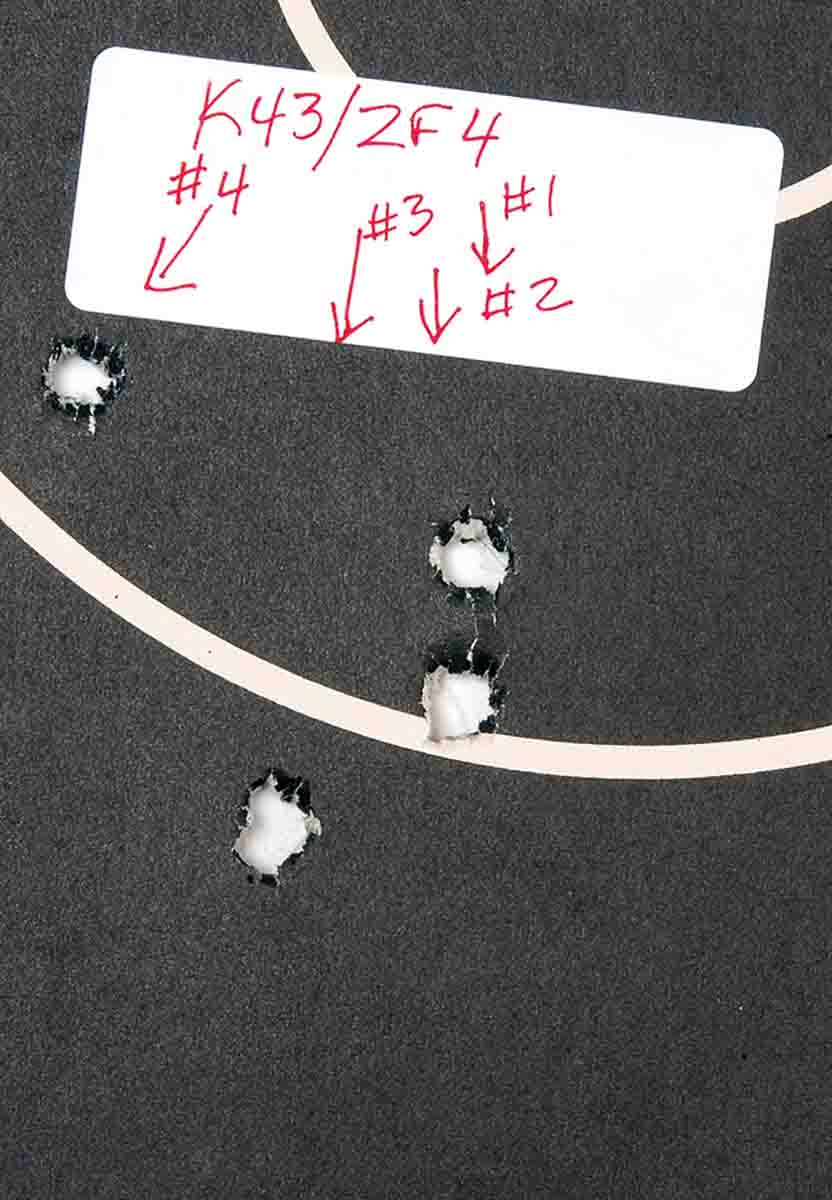

At this writing my collection includes two wartime-produced M1 Garands, two SVT40s and a single K43. I’ve shot all to one degree or the other. Some of this shooting was even done with original World War II production ammunition by the three nations, but most has been with my own handloads. Never with an M1 have I experienced a slam-fire but have with one of the SVT40s and the K43. It’s very disconcerting, so muzzle control is of prime importance when shooting. For handloading I use CCI’s mil-spec No. 34 primers. It was astonishing how far the empty case was flung by the K43 the first time the rifle was fired. It ended up at least 20 feet away. I can’t imagine what it was like for German landsers to the right of someone shooting a K43. On the Internet I found someone selling plugs for the gas system ranging from solid blocks to small apertures to stop or reduce the violence of its case ejection. My specimen has all matching numbers, so I block the gas port to prevent parts breakage during casual shooting.

In regard to sniper rifles and considering the best quality handloads, my scoped SVT40 possesses sufficient precision for a sniper rifle, about 1.5- to 2.0-MOA groups. The K43 does not. Its groups, even with a scope, are 2 to 3 MOA. For that reason experienced German snipers had little regard for the G/K43. On the plus side, removing the scope and replacing it does not appreciably change point of impact.

All three of these World War II semiautomatics served their respective armies well. An interesting minor fact is that photos of Germans packing SVT40s are common, but photos of Soviets or Americans with G/K43s are seldom if ever seen. Still, the M1 Garand was top of the heap in regard to service rendered. American GI’s firepower was the envy of their enemies.