Brownells' BRN16A1

Updating a Classic

feature By: Mike Venturino Photos by Yvonne Venturino | September, 19

Firearms writers either supported or criticized the rifles in their articles. One side said the new M16 was fragile. The other side countered that its light weight was worth the fragility. The naysayers called the M16’s chambering a “varmint cartridge.” The pro-16 writers said double the 5.56mm ammunition could be carried compared to 7.62mm NATO. The worst charge leveled at the M16 was that it wasn’t reliable. Those in favor said it was fine if kept clean.

There was truth on both sides of the controversy. At about 7.5 pounds, the new M16 was the lightest primary battle rifle the U.S. had ever fielded, albeit from Vietnam there were a few documented cases of M16s breaking into pieces when used as a club in hand-to-hand combat. That the new round was indeed a varmint cartridge has been proven beyond doubt; in its civilian dress, it’s the most popular cartridge in use. It did not have the “punch” of the 7.62 NATO, but many veteran combat units in Vietnam urged riflemen in the field to pack at least 20 magazines, or 400 rounds.

Since the M16 was the first American battle rifle where each one was capable of full-auto function, that ammunition supply for every individual was not excessive. Just to check, I weighed a full 20-round AR magazine. It weighed 10 ounces. A fully loaded M14 magazine with 20 rounds of 7.62 NATO ammunition weighed exactly one pound more.

(Every M14 manufactured was capable of fully automatic fire. However, most had a lock-out device preventing them from being used in that manner. A special tool was required to allow full-auto function. The reason each individual troop was not issued an M14 ready for fully automatic fire was that they were virtually impossible to control when shot in bursts. I’ve been fortunate to try a full-auto M14 and agree with that assessment.)

A true charge that nearly upset the boat between U.S. military forces and civilian manufacturers concerned the M16’s unreliability. Some soldier and U.S. Marine casualties were found in Vietnam with their M16 in pieces because they were trying to clear cartridge stoppages. Space won’t allow delving into this matter in depth. For readers with interest in knowing details, read The Gun by C.J. Chivers (2010). Its almost 500 pages contain documented information on the causes and cures of the M16’s stoppages. However, one fact in The Gun I found especially interesting is that developmental work of the 5.56mm cartridge and M16 was done with ammunition loaded with a DuPont noncommercial extruded propellant known as IMR-4475. However, for Vietnam combat, the issued ammunition contained a spherical powder, WC846.

AR-15s were first adopted by the U.S. Air Force for guards protecting air bases. Prior to the AR-15 circa 1960, those guards packed World War II vintage M1 .30 Carbines. When the U.S. Army adopted the new rifle in 1964, its name was changed to M16. In my research, I have been unable to positively ascertain whether or not the Air Force’s AR-15s were select fire. Most certainly the M16s were. By 1967, some of the M16’s faults were rectified. A forward assist button was incorporated at the right rear of the action. Its purpose was to aid in pushing recalcitrant cartridges into dirty chambers. This new version was the M16A1 (alteration one). Soon after its introduction, the three-prong flash hider was changed to one that was closed on the end because the earlier type tended to hang up in jungle foliage. Barrel length was 20 inches. Rifling twist rate and the sight arrangement stayed the same. The rifles’ finish was also changed to black.

As an aside, at this point I’d like to mention some facts about the 5.56mm as adopted by the military. A question often asked is: “Why didn’t the M16s designers just go with the already-in-production .222 Remington?” This is an intelligent question in that the .222 Remington has a case length of 1.700 inches and the 5.56mm case length is 1.760 inches. C. J. Chivers covers this issue well in The Gun. This is where U.S. Army bureaucrats got into the game, decreeing the new small-bore infantry rifle and its cartridge had to be capable of hitting and penetrating a steel army helmet at 500 yards. Never mind that even seeing a helmet at 500 yards is impossible, especially when using a rifle with peep sights. As a long-proven varmint cartridge, the .222 Remington could hit the helmet without difficulty, given a good rifle and powerful optics, but it proved to be marginal in the penetration department. Therefore, cartridge engineers lengthened the .222 Remington case to add a bit more powder. That raised the velocity of a .224-inch, 55-grain FMJ spitzer boat-tail bullet to 3,200 fps. It then penetrated the helmet. This round became the .223 Remington for the civilian market and 5.56mm among the armed forces.

(Along the way, some cartridge engineers tried stretching the case length to 1.850 inches. AR-15 designers felt the 1.760-inch case was more suitable. The 1.850-inch case was then introduced on the civilian market as the .222 Remington Magnum.)

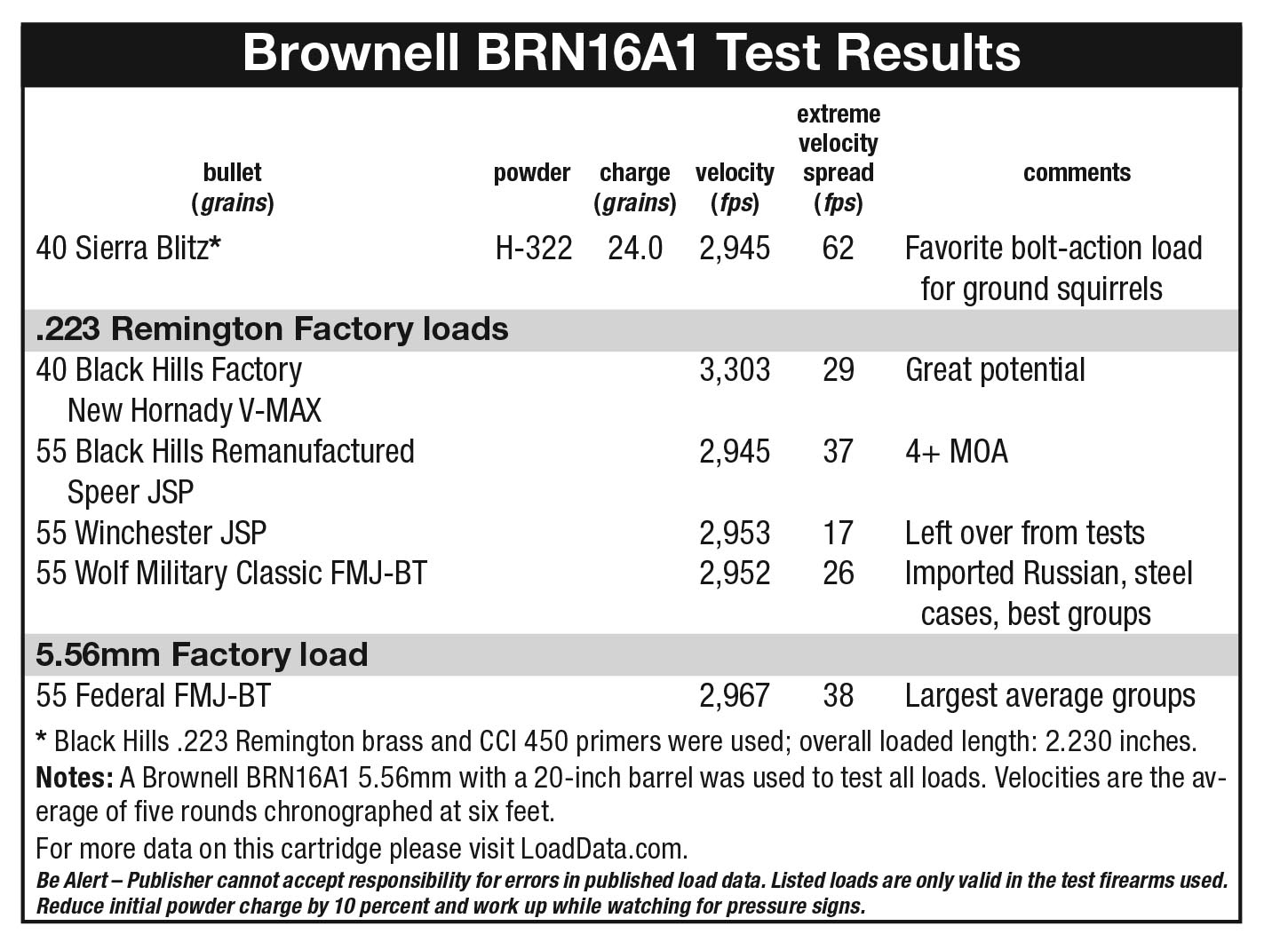

Brownells’ sample BRN16A1 arrived in the midst of one of the longest Montana winters I’ve ever experienced. I’ve therefore spent a lot more time handling the rifle than shooting it. Its caliber stamp is 5.56mm, so the frequent warning about shooting military-grade ammunition in a sporting rifle chamber does not apply. I have two other ARs on hand. One was made by a now-defunct company in Louisiana. It is stamped “.223/5.56.” The other is a Colt, and it is stamped “.223.”

Finally, I found what can only be considered an anomaly. The Brownells rifle has the usual two-stage trigger. However, the first stage, which is usually just free movement before the actual trigger pull begins, was heavier to pull than the actual trigger. I tried measuring them together and got an average of 8 pounds. With some deft finger manipulation I was able to hold the first trigger stage rearward while measuring the true trigger pull. It averaged 3 pounds. In firing, the first trigger stage moved rearward and stopped about three times prior to getting into the final 3-pound stage. A gunsmith could fix this in a jiffy, and it was the only problem I encountered while shooting a couple hundred rounds.

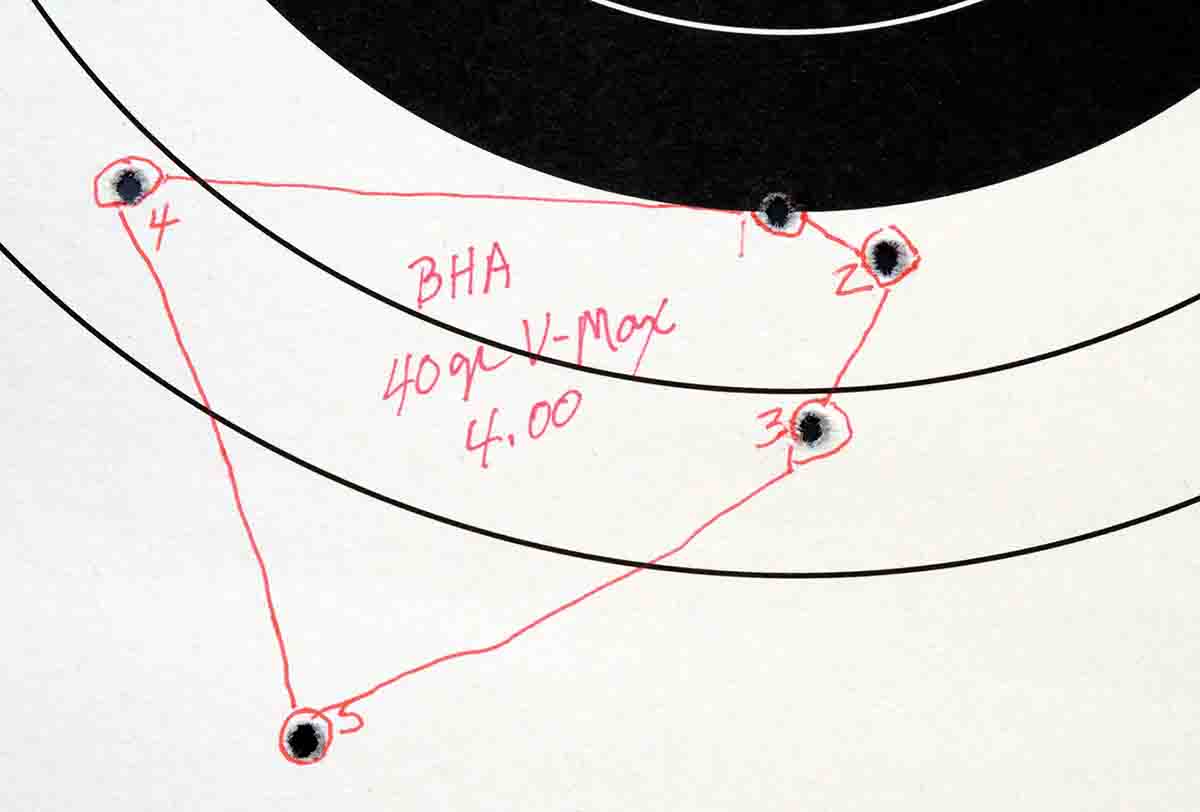

As soon as weather permitted, shooting the BRN16A1 at paper targets and gathering chronograph data began. The first thing learned was that the sights were off by several feet for both elevation and windage. Adjusting and shooting commenced with the tip of a polymer-nose bullet, which worked as well as an FMJ. Since more of the 40-grain loads were available, that is what I used to zero the rifle. Later shooting showed 55-grain bullets impacting about a foot lower at 100 yards.

As I have now reached the age of 70, I am sure my group shooting at 100 yards was hampered a bit by my eyesight. It seemed that good three-shot groups were far more likely with all loads than were good five-shot groups. As is proper for this replica of the M16A1, the carrying handle is not removable, and my own AR features optics for that reason. I expect the primary market for Brownells’ BRN16A1s is Vietnam veterans, or sons or daughters of vets who will want the closest thing to the original as possible.