Light Gunsmithing

Gunsmith Reference Material

column By: Gil Sengel | September, 19

The percussion cap changed everything; now there was fire among the powder grains as soon as the hammer hit the cap. There was no more waiting for a priming charge to burn through a hole in the barrel to get to the main event. Ignition seemed instantaneous; wingshooting became practical for the first time.

Suddenly, however, the gunsmith was called on to repair guns with hammers on the sides, top or bottom of arms that looked nothing like a flintlock. Then came the revolver, and the days of a lone gunsmith making complete firearms were over.

Of course, the percussion cap quickly became the centerfire primer in self-contained metallic cartridges designed for use in repeating arms. Guns became complex machines for feeding, firing and then expelling what remained of these cartridges. All designs had lots of little parts. A gunsmith often couldn’t just copy them in mild steel to replace one that was broken because of the need for special steels or heat treatment beyond simple case hardening.

Then there was parts wear. If a gun was shot much, often two or more parts would wear enough to cause malfunctions. Since nothing was broken, the unfortunate gunsmith had to determine which parts were worn, send them to the maker of the gun (if that was possible) so as to get the correct replacements and hope he was correct in his diagnosis. Many times the gunsmith had no experience with – or had even before seen – the arm he was asked to repair.

Obviously, the poor gunsmith needed some help. This had been made possible a bit earlier by a German chap named Gutenberg; the only problem was that printed material was hard to come by early on. Anyone working on guns latched onto any available material. The situation only got worse as more repeaters came along and semiautomatics appeared around the turn of the twentieth century.

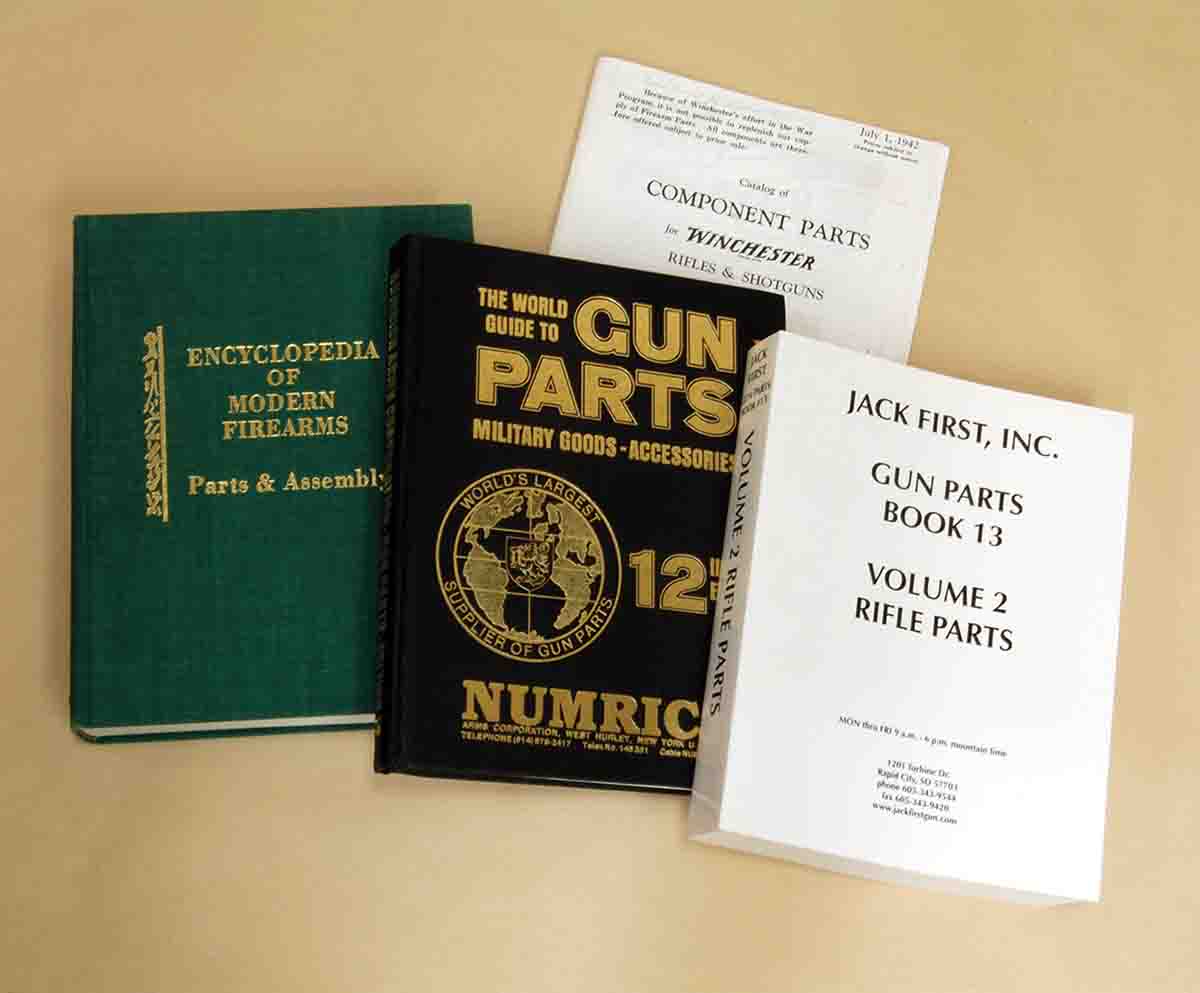

A few schools offering gunsmith degrees have appeared since the 1950s, but someone interested in gun work as a “hobby” can’t quit their day job to go to school. Fortunately, that’s not necessary today because, except for the artistic aspects of stockmaking, checkering and engraving, most of the rest can be gleaned from available reference sources. All that is required is patience to find what is needed.

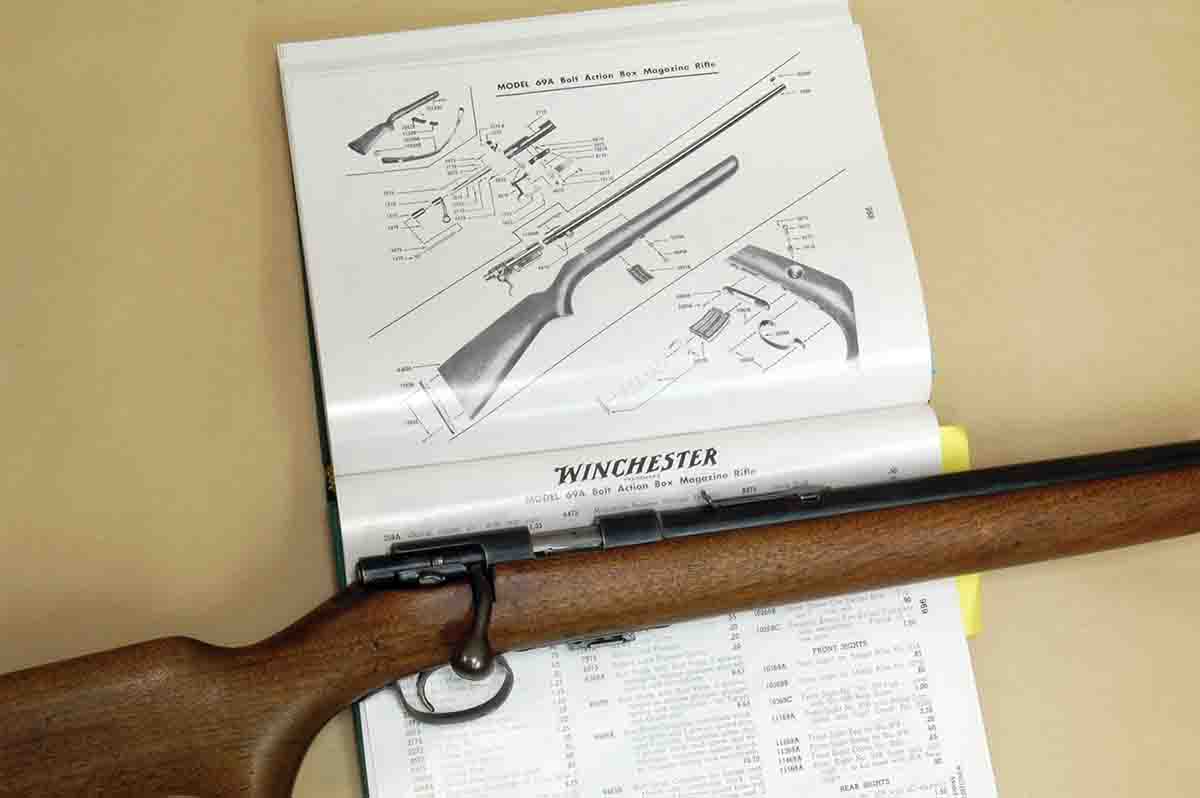

For example, I believe it was in the 1940s that what is called an exploded view first appeared. Here the mechanism is illustrated, then each part is shown at varying distances out from it – as if the object exploded. Lines radiating out to each part showing exactly where it appears in the illustration reinforce the illusion. It is a concept the mind quickly grasps, transferring a lot of knowledge without a word being written. These should be collected wherever possible.

Another source is factory service manuals provided by most large gunmakers in past years. Old copies of American Rifleman (about pre-1975) contain features and columns on gunsmithing and repair tips, exploded views and making tools to simplify disassembly. Sources for such old literature include gun shows and, surprisingly, antique shows where it is referred to as ephemera, literally paper items originally made to be used for a short time then thrown away.

For gunsmithing, today there are general books and many specialty volumes covering only one make and model. These can be very detailed, covering history and development or just disassembly/reassembly. Yes, reassembly instructions are very important for many guns because “reassemble in reverse order” doesn’t cut it anymore! A couple of the books shown in the photos are at Gun-Guides.com and provide disassembly/reassembly steps for specific firearms. Clear photos illustrate the text and show any special tools that may be needed. Best of all, they lay flat when opened; a good example of a modern firearms information source.

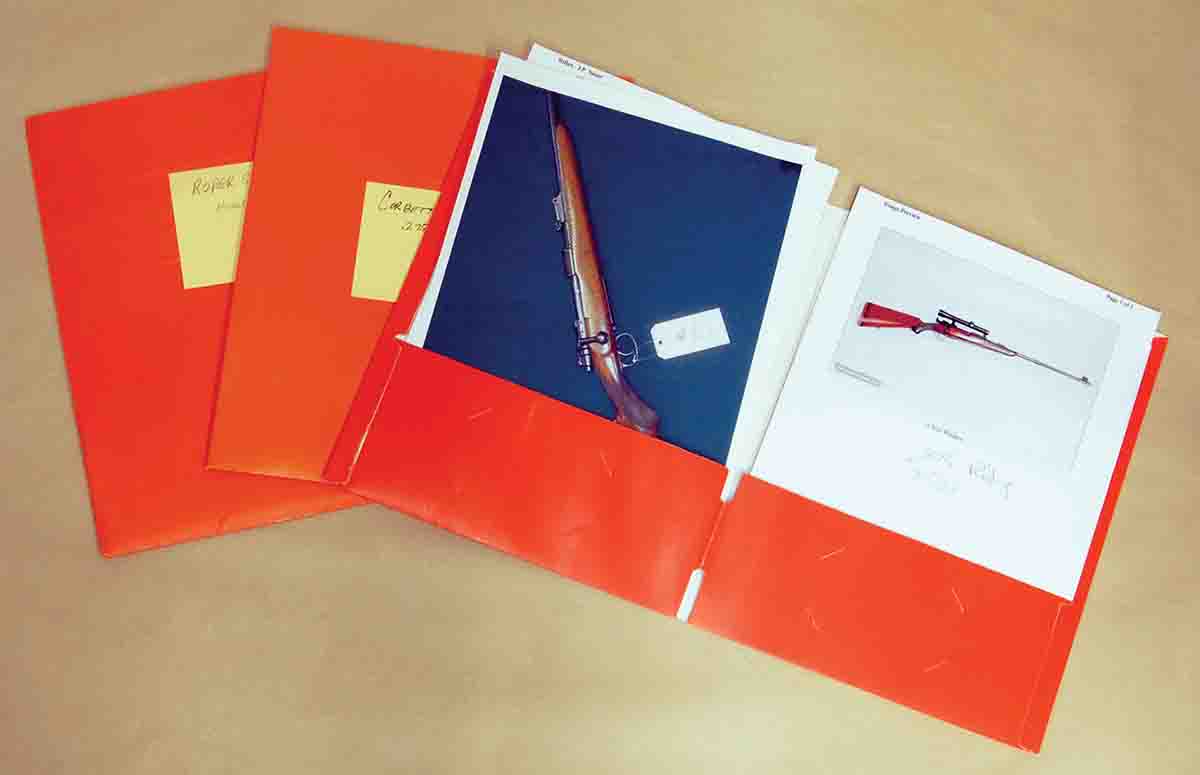

Another reason to collect reference material is today’s semiautomatic AR-type rifle, which has evolved over the years. Changes have been made to parts shape, materials, heat treating, surface coatings and design features. Thus, many parts and accessories aren’t interchangeable between guns. The only way to discover what fits what are the manufacturers’/accessory makers’ publications – or on the Internet, from which such information should be printed out and filed so it is available when needed.

Also important for rifles of this type are instructions for complete disassembly and lubrication. While it is possible to hunt for a lifetime with a bolt gun, single shot or pump action by doing no more than cleaning the bore and applying a couple drops of oil to moving parts, that won’t happen with a semiautomatic. Finding references describing how this is done for any model of interest will be time well spent.

Locating reference material on guns, gunsmithing and custom work can even lead to ideas for projects you had never thought of but suddenly can’t live without. Been there, done that: a Seymour Griffin-style Springfield sporter .22 Hornet on a Krag altered to single shot; .22 rimfire squirrel rifle on an early Hopkins & Allen falling block; perhaps a .577 Snider on a Martini or . . . the list is endless. Besides, it gives a perfect excuse to go to gun shows and antique shows, which is a whole lot more fun for intelligent folks than staring at the television!