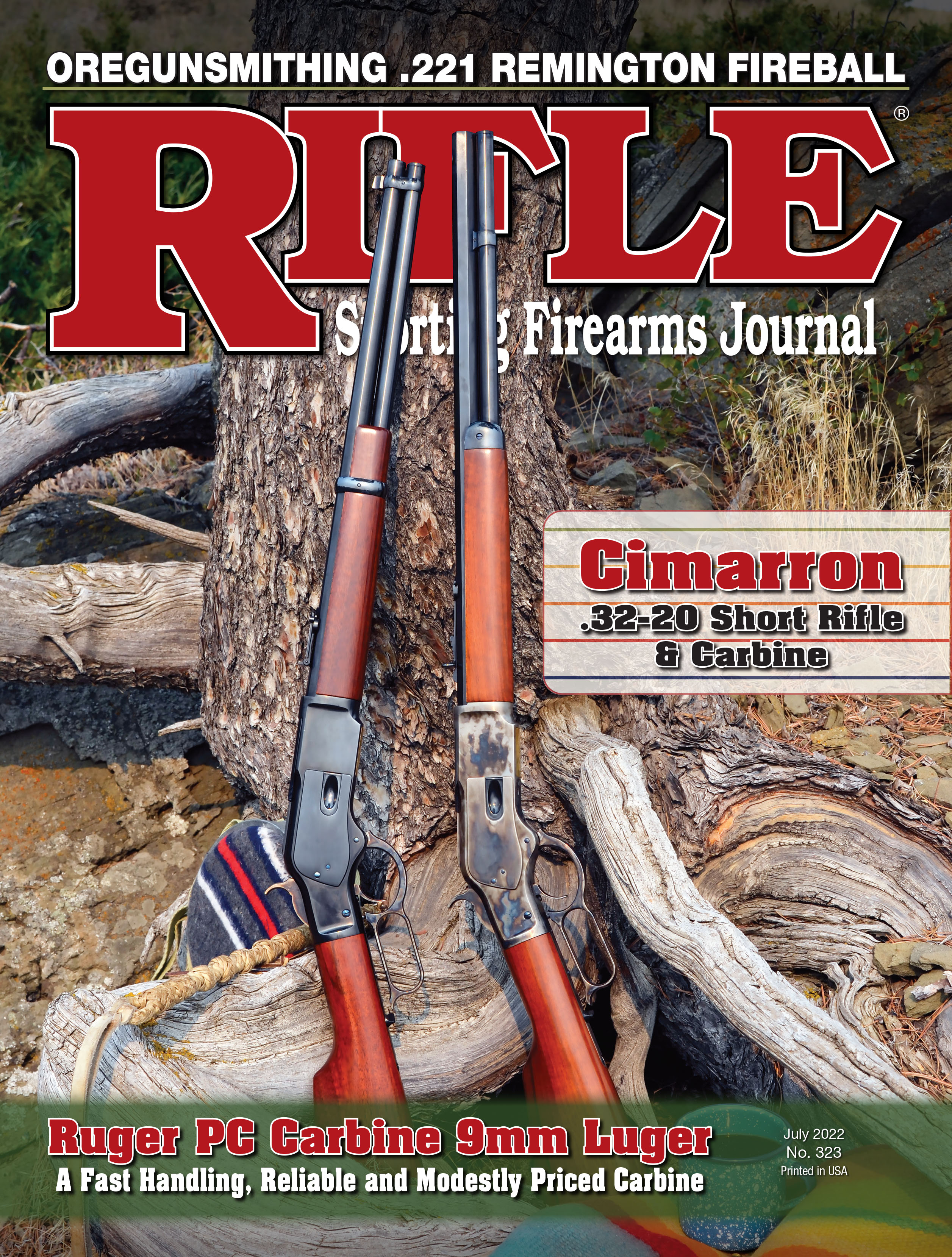

Cimarron

.32-20 Short Rifle & Carbine

feature By: Mike Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | July, 22

In the heyday of Winchester Repeating Arms Company lever guns, it offered muskets, standard rifles, short rifles and saddle ring carbines. My 50-year-old dictionary defines carbine simply as a short rifle. Winchester didn’t consider them so. It’s definition of a Model 1873 short rifle was that its configuration was exactly the same as a standard ’73 rifle, except its barrel length and magazine tube was 20 inches instead of 24 inches. Therefore, short rifles had crescent steel buttplates, steel forearm caps, buckhorn rear sights with blade fronts. Rear sight elevation was provided by a notched slider and both rear and front sights were dovetailed to either round or octagonal barrels. Therefore, they could be drifted laterally for windage zeroing.

On the other hand, Winchester ’73 carbines (actually saddle ring carbines) had wider, slightly curved steel buttplates, 20-inch lightweight round barrels with bands securing magazine tubes of equal length to barrels. Rear sights were folding ladder-types with sliding leaves for changing elevation. Front sights were blades pinned to studs silver soldered atop barrels. Windage zeroing could only be accomplished by drifting rear sights in their dovetails. A ’73 SRC cost about $1.50 less according to Winchester’s 1899 catalog.

(Author’s note: it should be pointed out here that we are speaking only of “standard” Model 1873s. Winchester accepted custom orders so buyers could have longer or shorter barrels than mentioned above, or half or three-quarters length magazine tubes and many other options. It was a buyer’s market in those days.)

From here on the story is personal. Late in 2020, I found a great deal on a 3rd Generation Colt SAA .32-20 with 7½ inch barrel. Over the long Montana winter, shooting, casting bullets and handloading for it was so pleasurable that a seed was planted in my brain. As in – perhaps I also needed a .32-20 lever gun. A ’73 was preferred because that was the introductory vehicle for .32 WCF, as Winchester termed the cartridge.

Although I have a rack full of original Winchester lever guns, none were currently in .32-20. Besides, this time I was aiming for a replica. The reason was that I wanted it to have a perfect bore for accuracy testing. With Montana gun shows mostly closed due to COVID-19, inspecting rifle bores bought my mail order would not be possible. “Easy enough” I thought, “I’ll just call Cimarron Arms for a loaner and then purchase it if

it’s a fine shooter.” Well it wasn’t quite so easy because my contact at Cimarron said it had exactly zero pistol cartridge lever guns in stock right then and didn’t know for sure when more would arrive from Italy.” (Italy also got whacked hard with COVID-19.)

“No problem!” I thought, surely internet sites would have plenty of Winchester-style .32-20 replicas at good prices. Again, not so. They were there, but not oodles of them. Nor were they inexpensive. This year is a seller’s firearms market! By this time, I had decided on a saddle ring carbine. I’d used a full size .32-20 Cimarron ’73 rifle when writing my book, SHOOTING LEVER GUNS OF THE OLD WEST. It shot very accurately but a full-size .32-20 ’73 rifle seemed a bit much in size and weight for such a puny round.

One evening while waiting for Yvonne in some store’s parking lot, I passed time by searching on my iPad for Cimarron .32-20s. On gunbroker.com there were a few SRs and SRCs and by the time Yvonne came from the store, I’d selected one, paid for it and made arrangements for my friendly FFL-guy to receive it. When she sat down, I proudly said, “Well I found my Cimarron .32-20 carbine and the deal is done.” She just shook her head and said, “Sometimes I think you need constant adult supervision.” (She thinks I’m impetuous.)

This time she was proven correct, for when I opened the newly arrived Cimarron carton, I had bought a SR instead of an SRC. (I checked back on the original order and indeed the company had sent what I had ordered.) So, I accepted the gaff and proceeded with learning about shooting, casting and handloading for .32-20 lever guns after a 25-year hiatus.

Right away, I relearned something important. Don’t load a lever gun’s magazine tube with more than one round until determining if the cartridge overall loaded length (OAL) is too long. For my Colt SAA, MP Molds’ 120-grain FP, its 115-grain HP, Arsenal Molds’ 98-grain SWC, Oregon Trail’s 115-grain commercially cast RN/FP and Missouri Bullet Company’s 115-grain coated RN/FP all shot well. Except for the Oregon Trail’s and MBC’s commercially cast bullets, none of the above bullets would function through the Cimarron ‘73’s action. Crimping groove location was the problem. All non-functioning bullets had crimping grooves that put OAL in the 1.63/1.64-inch range. If I had bothered to consult the Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook, 4th Edition, I would have learned that proper OAL for .32-20 lever guns is 1.592 inches. The bullets from Oregon Trail and MBC had crimp grooves giving a 1.55-inch OAL.

Of course, the obvious solution was to crimp over the Arsenal Mold’s 98-grain SWC’s front band and over the MP Molds’ bullet’s ogive so that overall loaded cartridge length was within limits. That was done and I thought my ’73 was in business except when more than five rounds were loaded in the tube magazine! As the magazine tube spring compressed its pressure began pushing bullets back into cases. Not only would such rounds not function through the cartridge lifter, bullets pushed back on smokeless powder charges can increase pressures dramatically. Such a problem never existed in the black powder-era because there was a case full of powder to keep bullets from been pushed down.

By this time, my frustration was building and my usual pressure release is buying a gun. This time, I got things right with a brand new Cimarron Model 1873 SRC. Both the SR and SRC are from Uberti of Italy with what I consider an attractive appearance. The SR has color case hardened frame and lever with forend cap, while the buttplate, barrel and magazine tube are nicely blued. All metal on the SRC is likewise nicely blued, except its lever is color case hardened. Of course, cartridge lifters for both are brass. The two-piece stocks are of European walnut with a reddish stain. Fit of wood to metal isn’t to custom gun quality level, but it’s much better than many American-made lever guns. As with original ’73 Winchesters, safeties are half-cock notches in the hammers.

Cimarron’s ‘73s do differ from original Winchesters a bit. For instance, Cimarron’s SRCs have 19-inch barrels instead of 20 inches as were Winchester’s. Also, SRC’s front sights are machined integral with the front barrel band instead of blades pinned on studs silver soldered to the barrel. I have seen that sight-on barrel band arrangement on some Winchester Model 1866 SRCs, but I don’t think such was the situation with ’73 SRCs. That’s not a big deal but needed mentioning.

Of course barrels on these ’73 replicas are totally different from each other. As proper, the SR’s barrel is octagonal and .78-inch wide at the muzzle. (Original Winchester rifle barrels could also be round, but I’ve never seen that option in the Italian replicas.) Conversely the SRC’s barrel is round as proper; only .63 inch at the muzzle. According to the owner’s manuals supplied with them, rifling twist is 1:20. Cimarron’s specifications call for .32-20 barrels to measure .311 inch across the grooves.

Stock length of pull on the Cimarron ’73s were 13.25 inches for SR and 13.50 inches for the SRC. The trigger pull weights averaged about 6.50 pounds each. I weighed both of these ‘73s and their differences surprised me. The SR weighed 8.25 pounds and the SRC was 7.75 pounds; a mere eight ounces difference.

Upon arrival, the SR hit point of aim for elevation at 25 yards with its rear sight’s slider bottomed out. A slight tap with the Wyoming Sight Drifter moved it laterally in its dovetail to the right for windage zeroing. (There’s a tiny “cramp” screw in both the front and rear sights, which must be loosened before drifting them.) With the Cimarron ‘73’s SRC sight folded down, its point of impact at 25 yards is 1.5 to 1.75 inches high depending upon exact load. Its rear sight needed drifting to the left about three-quarters of an inch. Again beware the “cramp” screw before pounding on the sight.

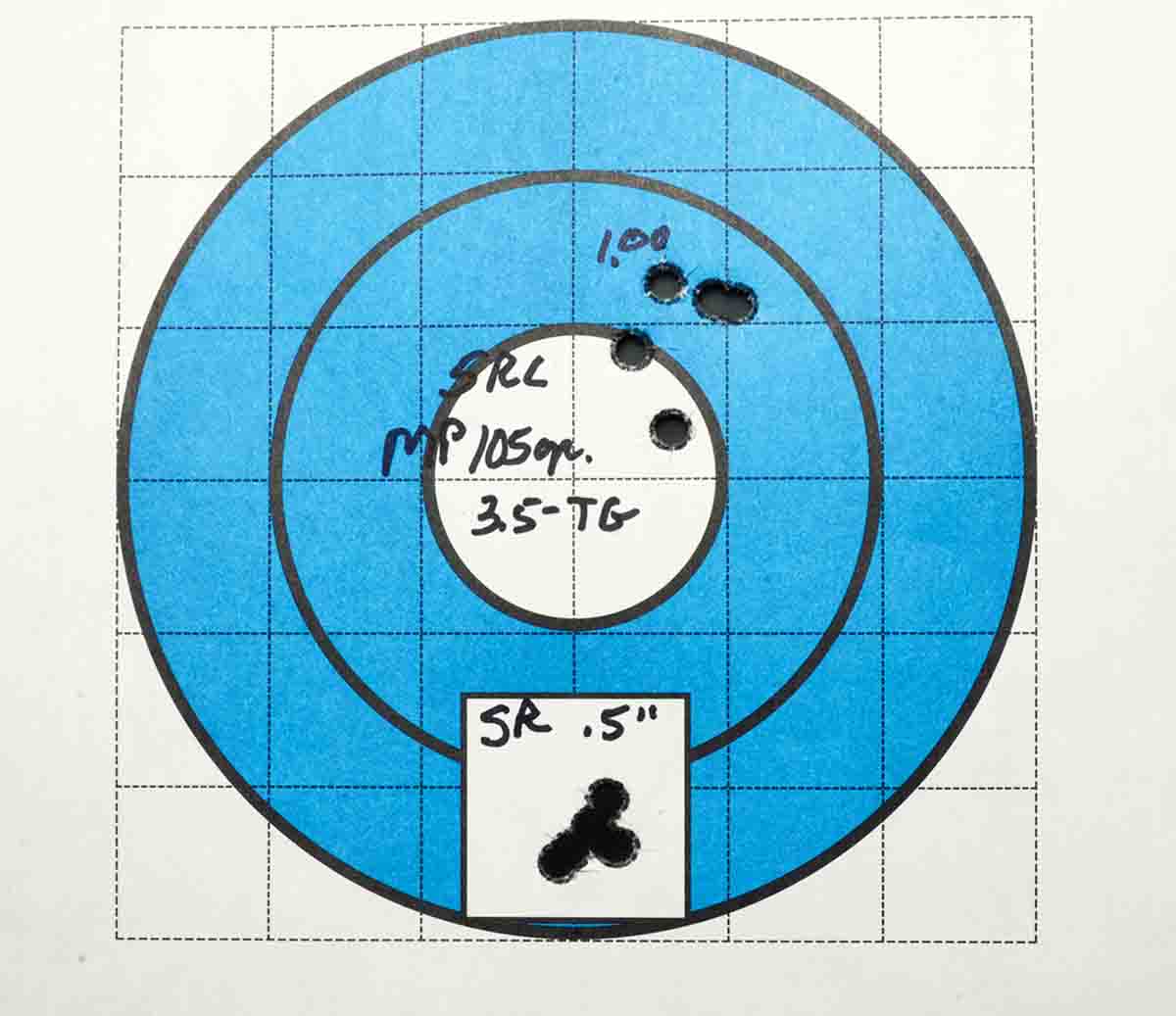

At this point, I should say why I was zeroing these .32-20s at such a short distance. One reason is that they are iron sighted, plinking or small-game/varmint rifles. They may have been used for deer in their heyday 120 years ago, but that’s not recommended today. Their rather thick sights quickly will blot out any small animals at any distance. Also, my part of Montana has few windless days. My group shooting with .32-20s was done at 25 yards to determine their capabilities of precision; not how far a 100/120-grain bullet at about 1,100 to 1,200 fps will drift at longer ranges. By my standards, if a 25-yard group is about an inch, give or take an eighth, it was perfectly acceptable; 1.5 inch groups are mediocre. Over that, and to me, the groups are downright poor.

Both the SR and SRC came from their boxes a little stiff in manipulation. As with all five of my original Winchester Model 1873s, there is also a small spring-loaded button on the bottom tang of these replica ‘73s. It must be depressed by closing the lever before ‘73s will fire. This is done as a safety feature to prevent firing before the bolt is fully in place. In the beginning, the SR required a conscious effort to depress that little nub, but after some use, the lever now pushes it into its recess smoothly. The SRC’s lever depressed the button easily from the beginning. In fact, after a few hundred rounds through each rifle, their actions have smoothed noticeably.

Now it’s time to return to the overall cartridge length and bullet crimping business. Once again, I turned to MP Molds of Slovenia. It had in stock a “convertible” four-cavity brass mould for the .32-20. Convertible means that by their ingenious plugs and pins system, any cavity can be converted to drop solid or hollowpoint bullets. The former weigh 105 grains of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy and the latter weigh 100 grains. All cavities drop bullets of 1:20 alloy at just over .313 inch, so my sizing die of that diameter just trues them up. This mould is my third order from MP Molds, and like the first two, it casts beautifully-formed bullets and it was in my hands within seven days of placing my order. While waiting for the new mould, by searching in my powder/bullet storage shed, I found a 500-round, sealed pack of .313 inch, 115-grain RN/FP bullets by the long gone AA Ltd. Company. They must date back at least 25 years.

Therefore, in this project, three bullets: 100-grain RN/HP, 105-grain RN/FP and 115-grain RN/FP were coupled with Bullseye, Winchester W-231, Titegroup and Unique. Crimping grooves on all three bullet designs were placed properly for use in lever guns. Sadly, all Oregon Trail and Missouri Bullet Company 115-grain RN/FPs had been expended in the Colt SAA .32-20 project. Primers were small rifle and the brass was Starline.

As the table shows, the best group was a half-inch with the SRC. It was fired with Bullseye and MP Molds’ 105-grain solid RN/FP. Highest velocity was 1,175 fps with Unique and the MP Mold’s 100-grain RN/HP. Interestingly, all loads gave higher velocities from the 19-inch barreled SRC than the 20-inch barrel of the SR.

I’ve owned many Uberti replicas of nineteenth-century Winchester lever guns and have yet to encounter a bad one. That also applies to these .32-20s. Either one will make a fine partner to my Colt SAA .32-20.

.jpg)