Down Range

Vintage Rifles and Twist Rates

column By: Mike Venturino | July, 21

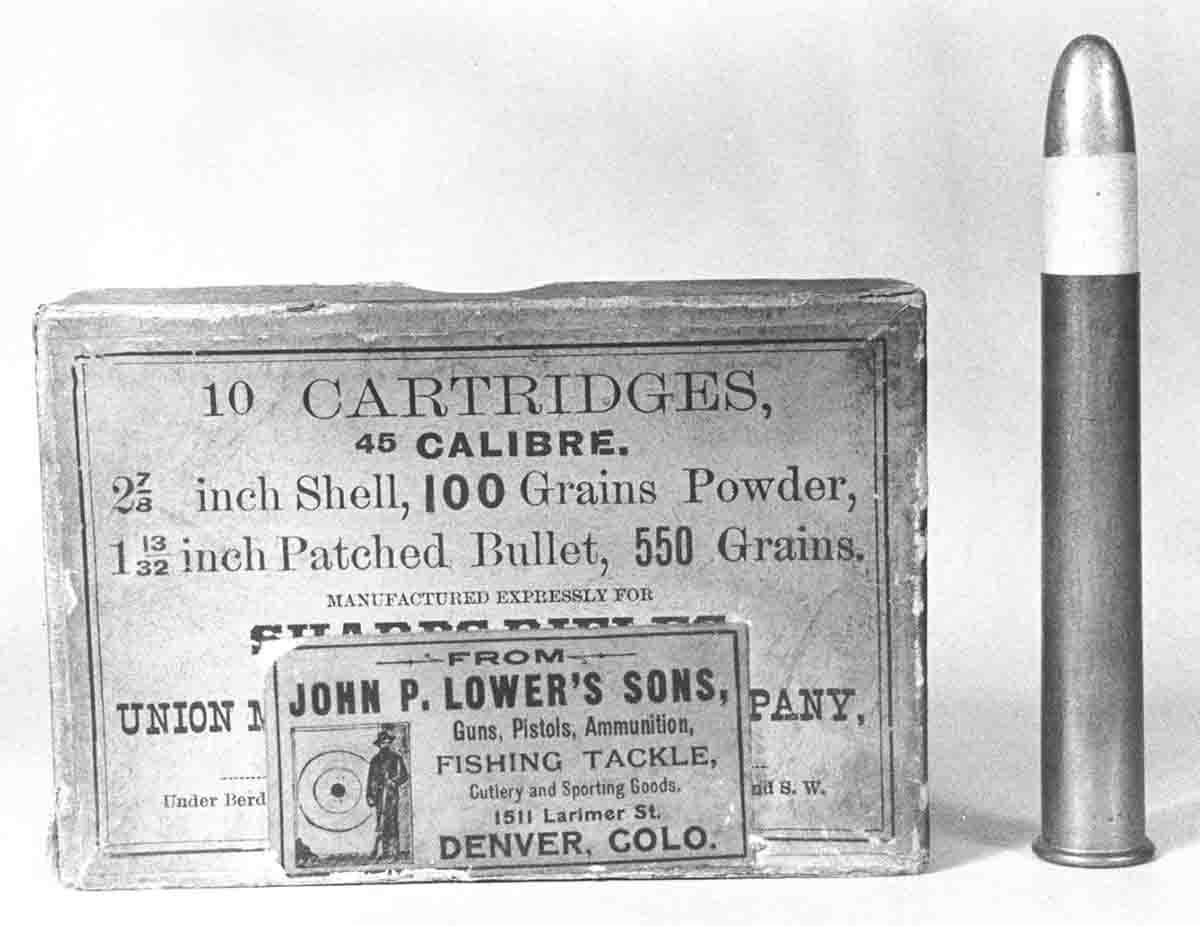

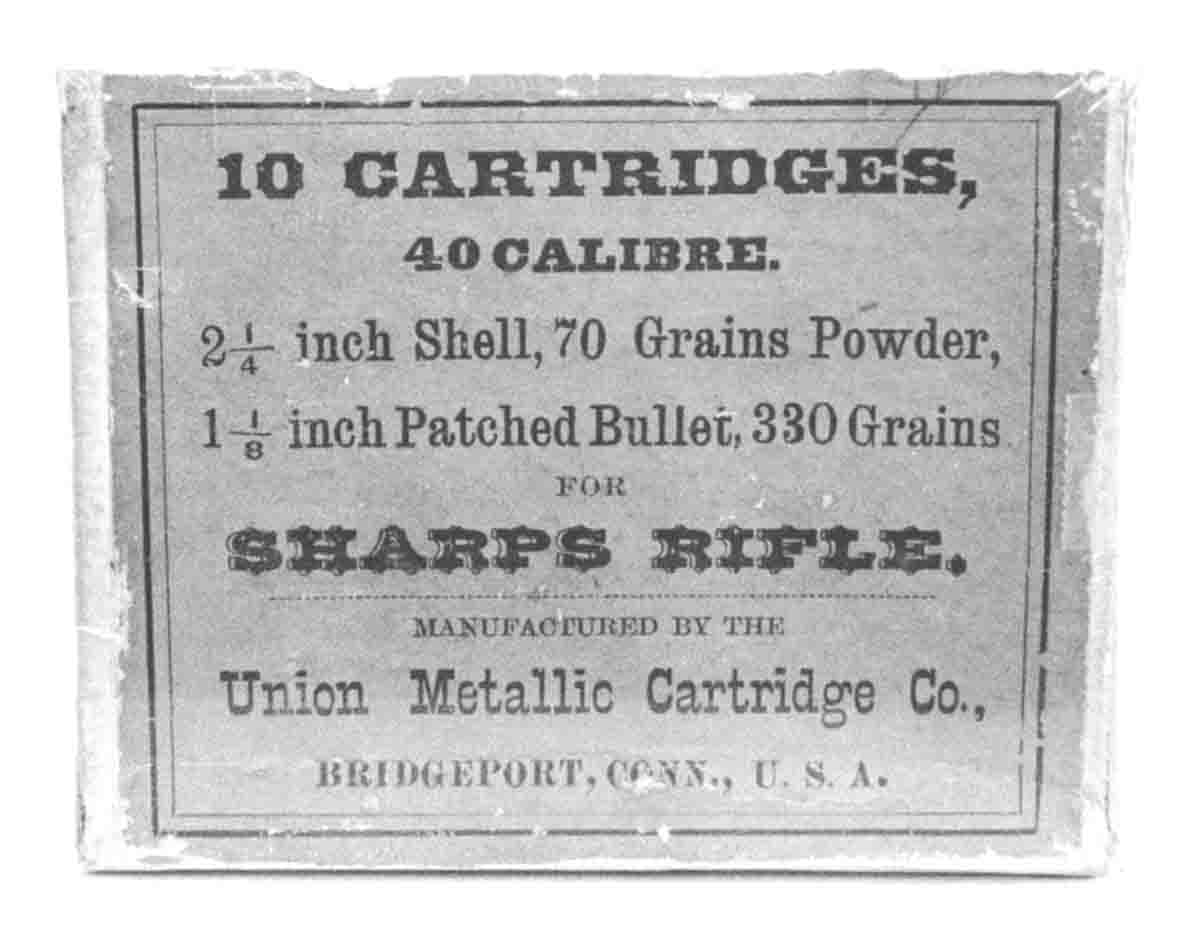

Nowadays, we speak of certain weights of bullets requiring certain rifling twists. An example is a box of Sierra .224-inch, 80-grain HPBTs stating on the label that barrels with 1:7 to 1:8 twists were needed. Actually, our modern method is slightly incorrect, as it is not the weight of the bullets that require certain rifling twists, but their lengths. In fact, in its 1870’s packaging of ammunition for Sharps rifles, the Union Metallic Cartridge Company included bullet length on its labels. For example, a 550-grain .45 bullet was 113⁄32 inches in length. A .44 bullet of 500 grains was 13⁄8 inches long.

After the U.S. Government adopted .50 Gov’t/.50-70 metallic cartridge firing rifles in 1866, the twist rate was tightened to 1:42. Although standard bullets for the .50-70 weighed 450 grains, they were only about an inch in length. It is written in the IDEAL HANDBOOK #28 (1927) and in CARTRIDGES OF THE WORLD 9th EDITION, that there were also .50-70 barrels with 1:24 twist rates. Lyman’s CAST BULLET HANDBOOK 4th EDITION stated the company tested .50-70 loads with a 1:24 twist test barrel. Nowhere could I find information about the Sharps Rifle Company’s .50-caliber twist rates, so I turned to a friend who owns both .50-70 and .50-90 originals. He used the tightly patched rotating cleaning rod method to check their barrels. The rod had made a full rotation at the end of both 30-inch barrels. That actually figures out to about a turn in 28 or so inches if discounting the 1.75- and 2.50-inch chambers.

By the 1870s, government ordnance department testers were busy working on the .45 Gov’t/ .45-70. The first bullet adopted for it was 405 grains and was about an inch long with a deep, hollow base. Model 1873 rifles and carbines got 1:22 twist rates. It wasn’t long thereafter when the Sharps Rifle Company brought out its version of .45-70 with barrels having a twist rate of a turn in 20 inches. That stuck for most .45 Sharps Sporting Rifles, although it has been written that some of its .45 target rifles got barrels with 1:18 twists. Sharps rifles were also produced in a number of .40-caliber cartridges with bullets ranging from 260 grains (.40-111⁄16 inch BN case) to 370 grains (.40-25⁄8 inch BN case.) Rifling twist rates for those that were 1:18 or 1:20, and they seemed to work well with the entire range of .40-caliber bullets.

When we get to Winchester Repeating Arms, I cannot help but believe that its technicians were kept busy trying to figure out rifling twists. That’s because they were spread all over the map. From the 1870s black-powder era until after the turn of the twentieth-century, early in the smokeless era Winchester’s rifling twist rates ran the gamut from 1:14 (405 Winchester) to 1:60 (.50-95 WCF).

Obviously, velocities had something to do with the differences. For example, the .40-72 WCF was a black-powder round for the Model 1895 lever gun. It used a 330-grain bullet in a case 2.58 inches long. In Winchester’s own 1899 load table, the company rated it as giving 1,359 fps from a 26-inch barrel. Model ’95s in that caliber have a 1:22 rifling twist. Then about 1905, the .405 Winchester arrived with a 300-grain bullet at about 2,200 fps. Winchester then tightened that caliber’s rifling twist rate to a turn in 14 inches.

For a moment, let’s turn to something a mite more confusing. Those are the twist rates given Winchester’s pistol-size cartridges used in Model 1873 and Model 1892 rifles and carbines. Those cartridges were also used in a variety of handguns. The .32 WCF/.32-20 was given a turn in 20 inches for Winchester’s lever guns. The .38 WCF/.38-40 and .44 WCF/.44-40 were both given 1:36 rifling. Now consider the Colt SAA. A work sheet I have from the Colt factory shows that those three cartridges all had 1:16 twist rates.

By the 1880s, Winchester developed its “Express” black-powder cartridges. Those had relatively light bullets for their bore sizes, and their rifles got slow rifling twists to match. For instance, .40-82 Winchester used 260-grain bullets and Model 1886 rifles so chambered had one turn in 28 inches for twist rate. Winchester’s .45-90 was factory loaded with 300-grain bullets. Rifles for it got a turn in 32 inches. The huge .50 Express (.50-110-300) got a slow 1:54 twist.

Almost all barrels made now for the above cartridges receive tighter rifling twists. Just using Shiloh Rifle Manufacturing for example, its .40s have a turn in 16 inches, its .45s get a turn in 18 inches and the company’s .50s receive a tight 1:22 twist.