Walnut Hill

Gearheads

column By: Terry Wieland | July, 21

I became an inveterate buyer of magazines and books about hunting, and invariably found myself rushing through in order to get to the part that interested me most: What did he use? And how did it perform?

To this day, when I reach the section where I see mention of a cartridge – .270, .30-06, whatever – I can feel my breath quicken. Old habits die hard.

In mountaineering and, presumably, other more arcane pursuits, they have a term: “Gearhead.” It usually denotes a guy (rarely, it seems, a girl) who is just as interested in the equipment of climbing as he is in the climbing itself. It’s almost as if the climbing is merely an excuse to buy every new gadget that comes along, or buy better gadgets to replace the ones you already have or buy backup gadgets in case a first-string gadget fails at the critical moment.

From photography to cycling to scuba diving to golf to fly fishing, we find people who are intrigued by the gadgetry to the point of obsession. I, fortunately, am not like that. Maybe it’s because, having been in this business for 35 years, I’ve long since ceased to be fascinated (if I ever was) by every new gadget that comes along. I do not want to own every little thing on display in the “New Products” section of the SHOT Show. Nor every big thing, for that matter. This, however, does not make me any less a gearhead, just less a “gadgeteer,” and we serious gearheads insist there’s a difference.

One of the earliest books I bought from the Outdoor Life Book Club was the Complete Book of Hunting, by Clyde Ormond. Ormond was a well-travelled hunter with a varied background. According to the dust jacket, he resigned as a school principal in 1938 and spent the next quarter-century hunting and writing about it. To show how well-rounded he was, he also held three patents for inventions, had played with a dance band and held a state license to box. Ormond was also a photographer, and if you look over that list, you will see some clues to his inner demons: Inventor? Photographer? Rifleman? Obviously, a gearhead! His magazine articles confirmed it. Of four that he published in Gun Digest between 1959 and 1967, three were about rifles and cartridges for specific animals, and the fourth about big-game rifles generally. In his Complete Guide, at least half the words are devoted to clothing, equipment, rifles, cartridges and optics.

In reading the book, my pulse always quickened when he got near the end of the chapter and the really important information: What rifle to carry, what bullet weight and the best type of scope. Still, it was always a means to an end, and the end was hunting – here, there, near and far. This is not always the case.

Various writers have told about acquaintances who become completely wrapped up in the equipment and devote hours to designing the ideal big-game rifle for, say, mountain goats, and then picking out a stock blank, agonizing over the dimensions, matching it with a barreled action, loading the best hunting bullets, and so on. Then, when it’s completed, it goes into the rifle rack where it’s pretty much ignored while its owner goes on to design the perfect elephant rifle, or a rifle for woodchucks.

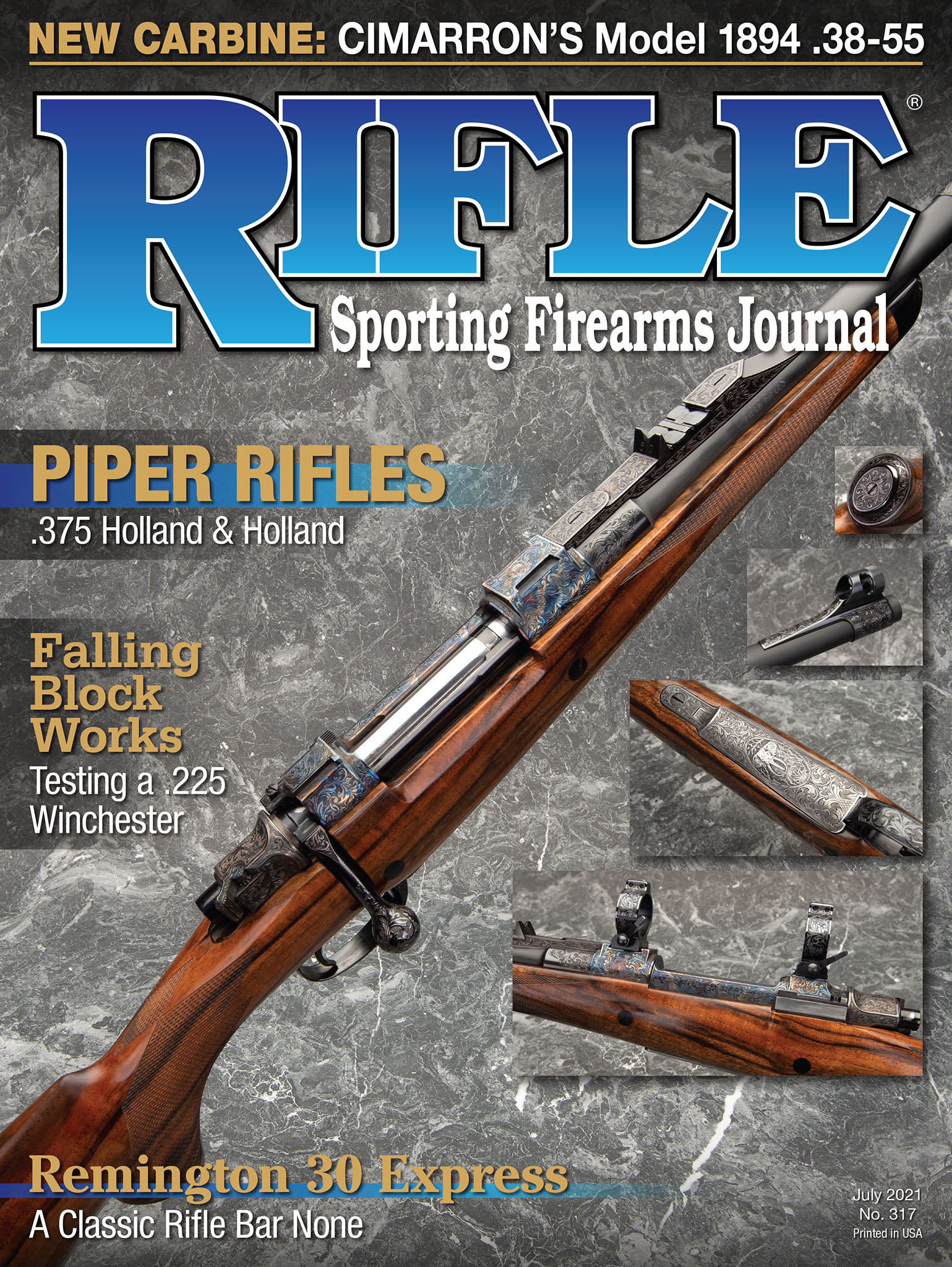

I’m suspicious that it’s always some “acquaintance” rather than a tacit admission of guilt, for I have known writers who were exactly that way. It reached an apogee in the heyday of the high-end custom rifle, with names like Biesen and Bolliger, Goens and Fisher, turning out masterpieces that were almost too pretty to hunt with. (Well, strike Biesen from that list, because his rifles were always made to be shot and hunted with and it showed, like the difference between a field-trial pointer and a real hunting dog.) But there were people who bought one custom rifle after another, each more spectacular than the last, studying and perfecting them down to the last detail, but then never doing anything with them that was really meaningful. Unless having your brother-in-law drooling in envy is meaningful for you.

Equipment junkies – a less techy name for gearheads – are laughed at by the crowd who are ultra-serious about hunting but barely know what caliber their rifle is, much less the make and model. They are characterized by guys who bluster inanities like “I use my guns hard!” The implication is not only that we don’t, but that our “fancy” rifles could not stand up to such use and would collapse, quivering in the nearest ditch if confronted by a hard rain or a rocky hillside.

For guys like that, rifles are disposable, on a par with tire irons or canoe paddles. They are simply an item of equipment. For those of us who read Clyde Ormond in our formative years, however, a rifle is almost a religious object, an icon of faith.

Some people might wonder, years after the custom-rifle mania has subsided, exactly what was accomplished by it all. The answer is that hunting rifles from the big manufacturers improved in any number of ways, just as hunting bullets from Remington and Winchester improved in the face of competition from Nosler, Swift and Trophy Bonded, while accuracy of factory ammunition improved because of benchrest shooting.

This does not apply to all factory rifles, of course. But now you can find a factory bolt rifle with a fine adjustable trigger, with a safety that works and with a stock that is actually suited to hunting and not just to shooting from a bench. Average accuracy is better overall, if you believe the so-called “test” reports, which I tend to view with a jaundiced eye. But pick up a new Winchester Model 70, Ruger 77, Browning, or anything from Blaser, Mauser or Sauer, and you can get both a fine trigger pull and accuracy that would have been cause for celebration and fireworks a generation ago.

This is not due entirely to the selfless dedication of those companies; a lot of the credit has to go to guys who knew exactly what they wanted and were willing to spend the bucks to get it from private craftsmen. And then, those rifles were written about, displayed, photographed and generally drawn to the attention of company marketing managers who were wondering how to sell more rifles.

The single most influential custom-rifle builder of the last 40 years is Kenny Jarrett of South Carolina, who created and popularized the “bean-field rifle,” setting off the craze for super-accuracy that continues to this day. This trend was accelerated by the exploits of military snipers in Afghanistan.

Kenny Jarrett, a champion benchrest shooter and southern whitetail hunter, was the first to guarantee half-minute-of-angle accuracy, the first to embrace composite stocks to the exclusion of walnut, the first to promote big glass from Europe with 30mm tubes and objective lenses the size of Coke bottles. All of this occurred in the 1980s, and was sparked by the need to be able to knock over a buck across the vast soybean fields that were cloaking the countryside. A 400-yard shot was really stretching it in the 1970s, but became almost routine with a Jarrett rifle.

Jarrett’s influence is obvious everywhere you look, although his hunting rifles are now considered to be old hat by many of the gearheads in the accuracy game. Still, what Kenny promised, Kenny delivered. There was no false advertising and no excuses. One famous photograph shows Kenny holding up a rifle he’d built which he sawed in half because it was not accurate enough.

Such ruthless honesty is one aspect of Kenny’s character that too few rifle companies are willing to emulate.