Dream Dakota

Galazan’s Fin De Siècle Custom Rifle

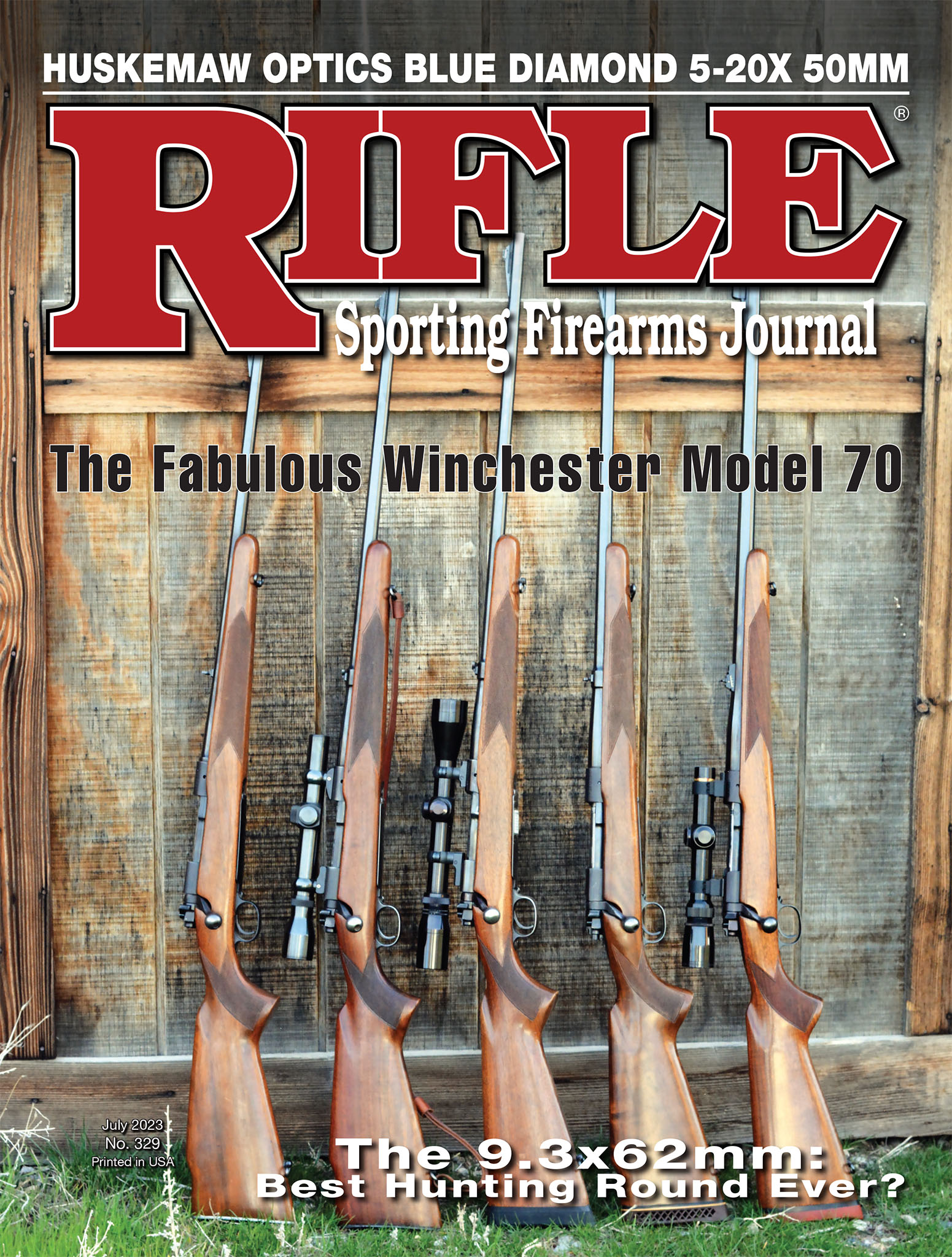

feature By: Terry Wieland | July, 23

However, by 1960, the final idealized form had arrived at: It was based on a Mauser 98 action, had a Winchester Model 70-style, three-position safety, a pistol-grip stock, and was chambered for the 30-06, 270 Winchester or, perhaps, the 257 Roberts.

There were, of course, variations: The pre-’64 Model 70 was equally as desirable, but the pre-’64 is merely a modified 98 anyway, and already incorporated some of the refinements that were de rigueur on custom rifles, such as a swept-back, low-rise bolt handle, hinged floorplate, graceful trigger guard, and so on.

Modifying Mauser 98s resulted in a cottage industry providing the necessary components to the trade, including bolt handles, bolt shrouds with three-position wing safeties and new bottom metal.

I first became aware of the Dakota around 1986, leafing through the Brownells catalog in the section devoted to actions for gunmakers. At the time, I’d been away from the world of rifles for a few years and was in the process of reacquainting myself. Naturally, my thoughts had turned to a new rifle and, although finances did not permit it, preferably one custom-made to my taste.

What I remember most about that catalog entry was the price: A Dakota action would cost $1,500, where a Mauser Mark X (the commercial Yugoslav Zastava) was less than a third of that. To a bolt-rifle lover, however, even the photograph of the Dakota action, in the white, was enough to set me to drooling. Something about those beautifully machined surfaces.

The other name mainly associated with the Dakota 76 is Gunsmith Pete Grisel, and I have heard (or heard of) several others claiming a share of the credit, including some early editors of Rifle. Who or what did what to whom is not my concern here. Undoubtedly, there were many conversations in many hotel rooms over many a tall one before the final form was agreed upon – if it ever was, which given the herding-cats nature of custom gunmakers, is highly doubtful.

In 1991, when I acquired my first one, the retail price on the basic rifle was a little more than $2,000. It had a stock of nice walnut with no Monte Carlo comb and a plain forend tip, in 30-06. I carried that rifle in Africa and America for the next decade.

What happened with Dakota in 2004, after Allen’s death from cancer, is a sad story of acquisition by, first, a rapacious investment fund, descent into bankruptcy, mismanagement and corruption on a grand scale – grand for Sturgis, anyway. It was acquired by Remington to become its custom shop. With Remington’s subsequent troubles, Dakota went into limbo, as far as I could determine, and finally reemerged as, today, Parkwest Arms.

Allen was intent on creating a company that produced a range of rifles, not just one type. To that end, he designed a beautiful, little, hammerless, single-shot action, with an underlever and falling block, as well as a less expensive version of the 76 action, called the 96. The 96’s cylindrical form was easier to bed than the flat 76. He even designed a side-by-side shotgun, and produced at least one in partnership with a European company.

One notable variation on the 76 was a takedown model called the “Traveler,” which of course, sold for more money.

At one point in the 1990s, a writer was sent a Dakota 76 to test, and was disappointed with its accuracy, which did not measure up to the much admired Kenny Jarrett standard of half-minute-of-angle groups. Of course, nothing else did in those days, but expectations for custom rifles were rising, and the Dakota – handsome and beautifully made though it was – did not measure up. When asked, Allen reportedly said, “They aren’t made for that.”

The Dakotas of the day were hunting rifles, not benchrest rifles, and there is much more to a good hunting rifle than simple accuracy, including reliability, ruggedness, smooth and quiet operation, weight and handiness, but this seemed to be lost on an accuracy-obsessed public.

My own 30-06 Dakota won no prizes for accuracy, being capable of about 1.5-inch, five-shot groups with handloaded 165-grain Bear Claws, but I took a lot of game with it in both Africa and America.

Over the years, I also owned a 458 Lott built on a standard Dakota action, another Lott on a Traveler, a 450 Dakota on the magnum action, and a 250-3000 Savage custom built on one of the No. 10 single shots. I took one Cape buffalo with the standard Lott. I eventually got rid of them all, not least because I refused to endorse the company, even implicitly, during its bad period after 2004.

For those not familiar with it, CSMC manufactures the current A.H. Fox, Parker, Winchester 21 and Auguste Francotte shotguns, as well as its own original double-gun designs, both side-by-sides and over/unders. It employs some of the best gunmakers and engravers in America, and uses production methods for high-quality manufacturing that have industry people from all over the world traveling to New Britain, Connecticut, to see how they do it.

The rifle shown here is a Dakota Traveler, chambered in 300 Holland & Holland, engraved and adorned in the finest no-holds-barred style, fitted with Talley mounts and a Meopta scope. Its list price is about $32,000, purchased from CSMC, which sells direct and has no dealers. Tony Galazan is not noted for underpricing anything, but even so that is an eye-watering price for an off-the-shelf rifle, which this is, having not been built especially for one client.

The rifle weighs in at a rather hefty 11.5 pounds, with scope, sling, and a full magazine, so it is not something one might want to lug up a mountain.

I have a hunch that anyone who would lay out $32,000 for a 300 H&H is not likely to load his own ammunition, so the immediate question was, how does it shoot with factory loads? I happened to have a stash of Federal Premium loaded with 180-grain Trophy Tip bullets. I fired five shots at 35 yards to establish the sighting, five more at 100, and then 10 shots at 200 yards. A 10-shot group at 200 yards tells me everything I need to know.

The rifle put 10 shots into 2.85 inches at 200 yards, and that is extremely fine performance for any big-game rifle, particularly using off-the-shelf ammunition, premium or otherwise.

For the record, at 100 yards, the Galazan Dakota’s five-shot group measured 1.90 inches, and at 35 yards, 1.1 inches, or .480 inch with a flyer. I wanted to see how the 35-yard setting applied at longer distances, so I did not make any adjustments between groups.

It has become an article of faith that no takedown rifle can be as accurate as one with a fixed barrel. There is no way of proving that definitively one way or the other, but this Traveler certainly seems capable of holding its own. We’ll see how it does when the weather warms up, the flooding subsides and I can do some load development for it.

At the range, the rifle got some admiring looks, but also a few comments such as “No rifle is worth that much money!” Well, any article is worth exactly what someone else is willing to pay. This rifle is certainly a feast to look at – albeit not to my taste – and that is a big factor in how much someone is willing to part with.

From the 1960s onward, custom bolt-action rifles progressed in several directions, with some becoming more ornate, others more accurate, still others having smoother operation and custom features. Some of the rifles turned out by Holland & Holland during the 1990s defy description and were priced to match. One American custom riflemaker even announced its intention of producing the absolute ultimate bolt rifle and set a price on it of $180,000. Whether it was ever made, much less sold, I have no idea.

There’s a term in the art world: fin de siècle. It is generally taken to mean the ultimate expression, often decadent, of a movement that has come to an end. It could certainly apply to the end of a golden age, such as we saw in custom bolt-action rifles from 1960 to 2010. If so, this Galazan Dakota would be a fitting exclamation mark, combining tradition, innovation, workmanship, fabulous adornment and sheer utility as a hunting rifle.

So: $32,000? You tell me.