Light Gunsmithing

H&R Single Shot Project Part II

column By: Gil Sengel | July, 19

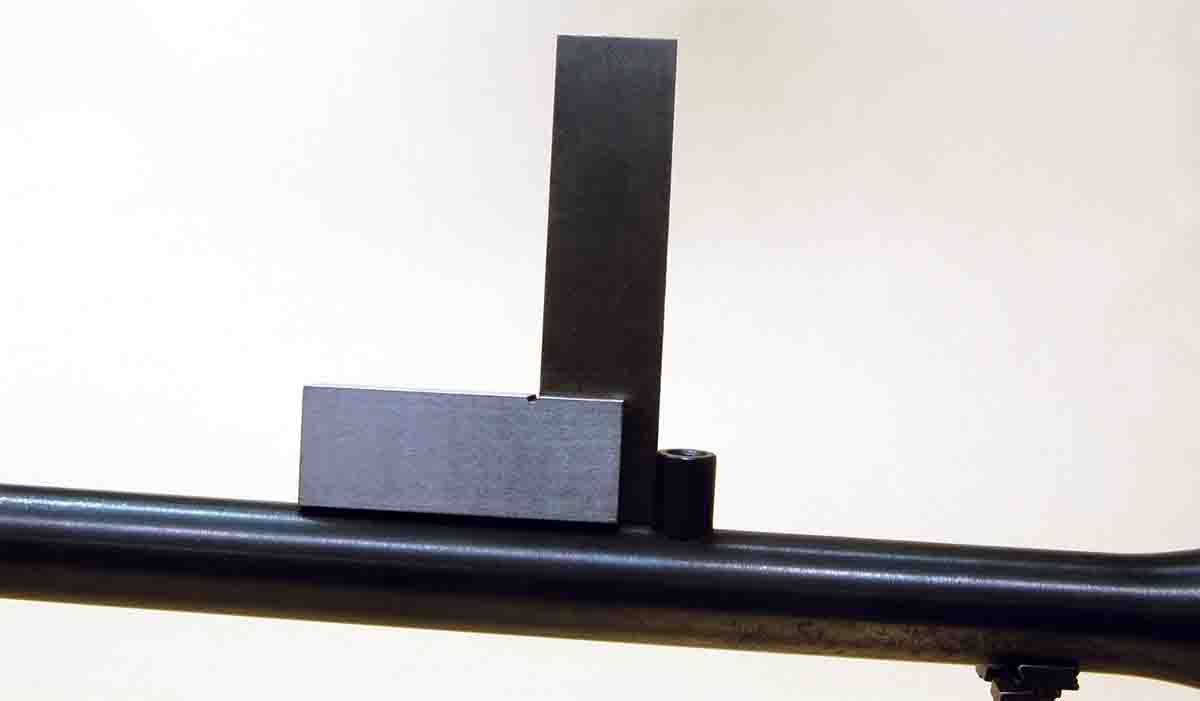

Here we modify the forearm attachment which, like the buttstock, was designed to keep manufacturing cost low. H&R simply silver soldered a piece of round rod (post) onto the barrel at 90 degrees to the bore axis. A 1⁄4x28 tpi hole passed through the rod lengthwise. These posts varied somewhat in diameter and occasionally were larger at the solder joint. Shown in a photo is a straight, .375-inch diameter post. A hole is drilled in the forearm, and a countersunk screw is used to attach the forearm to the barrel.

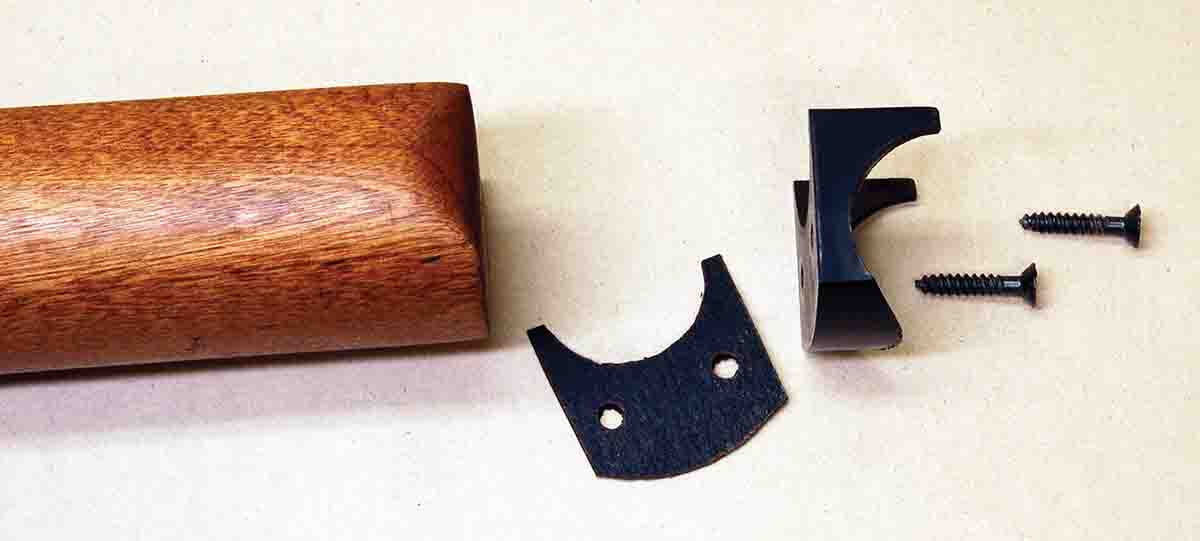

Anyone familiar with break-open guns knows the forearm wood attaches to the front, or “knuckle” of the action via a part known as the “forearm iron.” However, in this case it’s not metal at all but a synthetic material such as nylon or acetal. Contacting surfaces are semicircular so the barrel can rotate down when the rifle is opened for loading.

With the action closed, if the forearm is either removed or reinstalled, it will scribe an arc because of the semicircular forearm iron. There is no way a forearm moving in an arc can fit over a vertical post on the barrel and maintain a tight fit to the receiver. Since position of the attaching screw is fixed, the best that can be done is to enlarge the hole in the forearm until it fits over the post and sits down on the barrel.

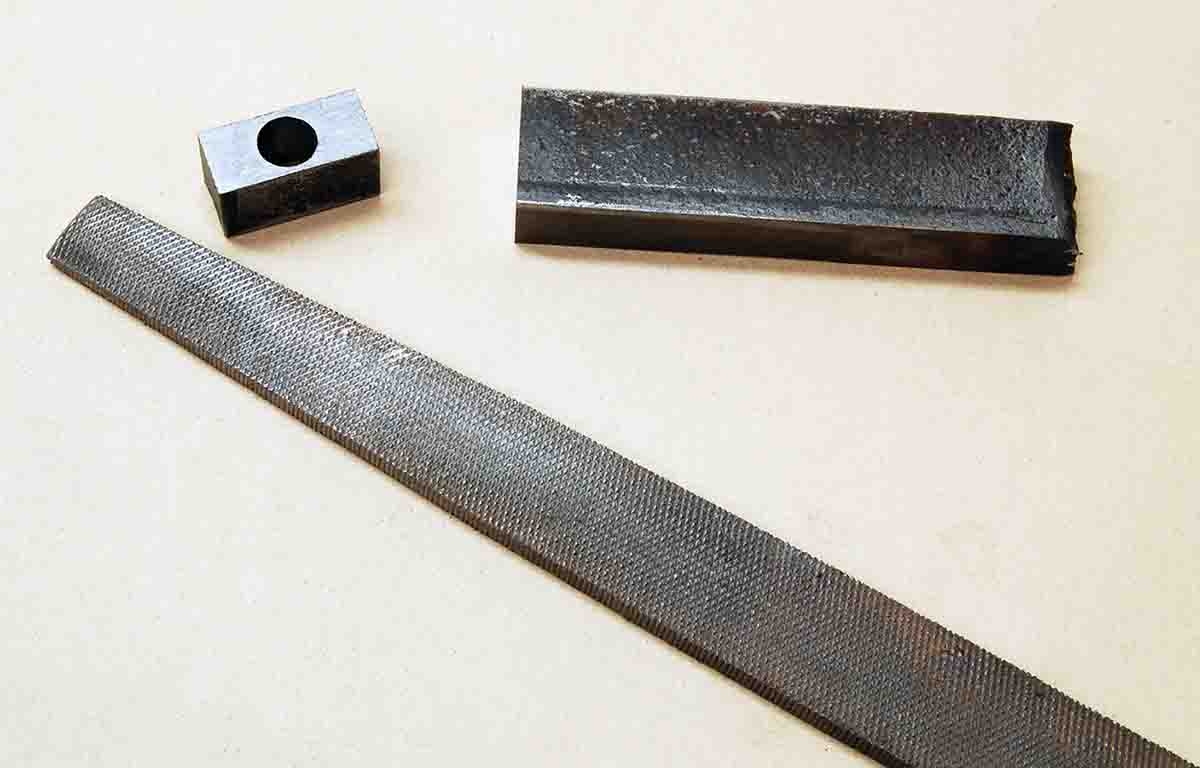

Begin with a small piece of half-inch-thick cold-rolled steel plate. This is cut and filed to a length of about one inch (not critical) and a width equal to the height of the post on the barrel. All surfaces must be as square to the cold-rolled faces as possible. Now turn the half-inch edge up and drill a hole of the same diameter as the post down through the center of the block.

The newly drilled block is now dropped over the post. Note the bottom of the block is flat, and the barrel is round. The block must be reshaped with a half-round file until it matches the barrel. Take the time to get this as close as possible because the better the fit, the stronger the solder joint.

Now for the most important part: Remember, the forearm moves in an arc as it is pushed down into place on the barrel. If the rear surface (toward the breech end of the barrel) of the new block remains at a right angle to the barrel, the forearm can fit no better than it did on the original post. If, however, the rear surface is angled forward 10 degrees (about .1 inch), the arc of the forearm is compensated for. The forearm can now be fit solidly to the block. This is exactly the method used on 99 percent of all break-open guns ever made.

Soldering steel was covered in this column in Rifle No. 235 and is very easy if the proper solder and matching flux are used. Cleaning the metal surface is very important. If the newly made block was just fit to the barrel contour, that surface is clean. Drop the block over the barrel post, trace around it where it touches the barrel and gently file through the blued surface down to clean metal. Scratching up the surrounding bluing with soapstone or welder’s chalk will prevent flux or solder from damaging bluing.

Heat the block first because it is small and heats quickly. Apply a small amount of flux with a toothpick to just cover the area to be joined. Melt a very thin coat of solder on this surface. Remember, never point the flame at the surface to be

Inletting the forearm wood comes next. Do this by cutting a half-inch-wide slot just long enough and deep enough to allow the forearm to swing into place, and the attaching screw will tighten easily. Note that nothing has been done to accommodate the

Since a new stock was made for this rifle in the last column, a forearm was included. A complete rifle is shown, though it’s not yet checkered. Now tight and solid, when a 4x scope is attached some handload combinations will provide five-shot groups of 1.25 inches at 100 yards – interesting entertainment for anyone who likes single-shot rifles in all their varieties.