Walnut Hill

Buckhorn Sights

column By: Terry Wieland | July, 19

For those who have not had the pleasure, the buckhorn sight is fitted into a dovetail slot at the rear of the barrel. Instead of a simple leaf with a little ‘V’ notch, however, it has great soaring “ears” on each side, like the antlers of a red stag – hence the name. These ears blot out the surrounding countryside as well as most of the target while contributing nothing, allegedly, to the positioning of the front sight. In low light, they actually make it harder to see the front bead.

There is a slightly modified version called the “semi-buckhorn,” the ears of which only go up about half as far but get in the way almost as much. If this was supposed to assuage the critics, it did not. I could quote many authorities but will limit myself to just one: Jack O’Connor wrote, “The worst open sight is the Rocky Mountain buckhorn or semi-buckhorn sight which blots out about three-fourths of the game, as these sights have big ‘horns’ or ‘ears’ sticking up on either side of the ‘U’ or ‘V’. Exactly what the function of those horns was supposed to have been in the first place, except to look fancy, I have not been able to dope out in forty years of melancholy brooding.”

But here’s the thing: Making a buckhorn sight is considerably more complicated and expensive than a simple standing leaf, so there must have been a reason and, one assumes, a good one.

There is a modern tendency to sneer at mysterious things that come down to us from times past as the follies of “idiots” who didn’t know as much as we do. Garry James, my friendly firearms historian who keeps up with trends more than I do – Garry is from California originally, which may explain it – says this is known as “now-ism.” It’s the belief that anything now is better than anything older.

Neither Garry nor I are fans of such thinking. One does not have to read much about gun inventors from the past – from Ferdinand von Mannlicher to Frederich Beesley to John M. Browning – to realize that these were very smart men indeed, highly skilled and ingenious. That being the case, starting from the premise that there must have been a reason even for something as seemingly idiotic as the buckhorn sight, what could it have been?

Bob Hayley, the Seymour, Texas, custom ammunition maker, has studied the technicalities of shooting artifacts of the nineteenth century more than anyone I know. He suggested that such sights were first fitted on the old Pennsylvania long rifles, which were intended for mostly short-range shooting in deep woods. For this use, he said, the big rounded aperture formed by the horns of the sight acted exactly like a later aperture sight on the tang or the receiver. You threw the gun to your shoulder, found the front bead by looking through (not at) the rear sight, and pulled the trigger. It was more than accurate enough, he says, for a deer at fifty paces.

Garry James does not agree. He has never seen one of those old rifles with such a sight and has studied many, both American and European, over the years. Muzzleloaders are not my area, but searching through literature, I could not find any reference to a buckhorn sight, per se, before the advent of the cartridge rifle.

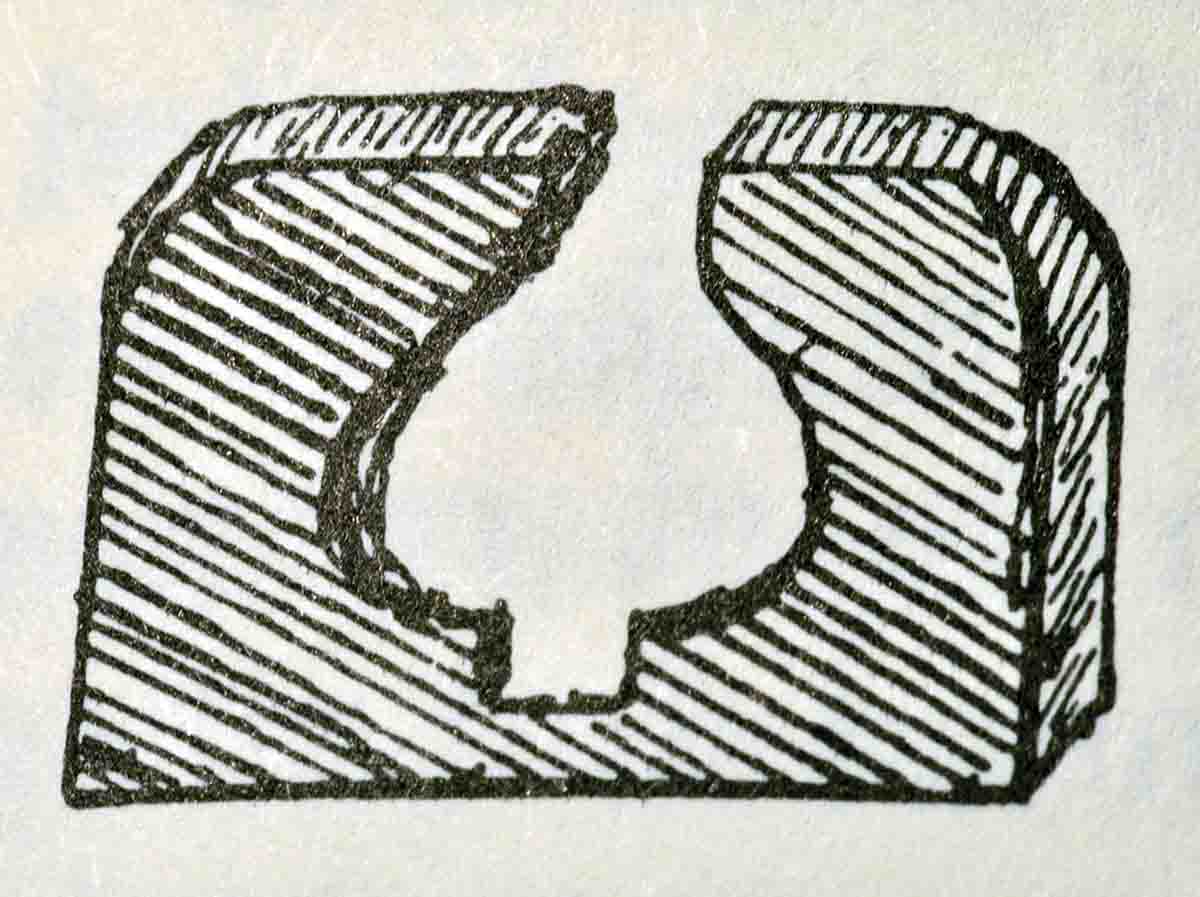

There is a hint to be found in Ned Roberts’ The Muzzle-Loading Cap Lock Rifle, originally published in 1940. He includes a sketch of a rear sight, similar to the buckhorn, with a spade-shaped aperture, on a rifle made before the Civil War by G.B. Fogg, a New Hampshire gunmaker. The rifle had a front bead on a tall stem. To shoot at 110 yards (20 rods – a standard target distance) the bead was positioned at the bottom notch; to shoot at 40 rods (220 yards) it was held just above the ears. Roberts considered this “especially practical.”

Roberts also states that the buckhorn sight originated in California and only spread east in the latter part of the nineteenth century, but small makers such as Fogg had their own patterns that predated it.

While researching a book on hunting rifles of the past, I kept coming across references to “drawing a fine bead,” or “taking a coarse bead” when a hunter was dealing with an animal either up close or far away. When the astonishingly flat-shooting .280 Ross was sprung upon the world in 1910, the M-10 sporting rifle had one standing leaf with “500” engraved upon it. Supposedly, the .280 had such a flat trajectory that a man could shoot accurately all the way out to 500 yards simply by taking more or less bead in the shallow notch.

The buckhorn sight as we know it originated in the era of black-powder cartridges, which all had looping trajectories. Could it be, I wondered, that the buckhorn was intended to be a two- or even three-distance sight, like Fogg’s? For close-in work the bead could be drawn down finely into the notch at the bottom, but for long distances the bead could be centered between the points of the ears as they curved around. If you knew the capabilities of your rifle – and most one-gun hunters did – then you would know the distance for which this would be accurate. Obviously, for anything in between, the bead could be centered in the middle of the aperture formed by the ears, exactly the way a later receiver sight worked. Generally, the aperture of a buckhorn sight is large enough to allow this.

In fact, since these sights have a sliding ramp with multiple steps that allow setting elevation, you could sight it in in such a way that the middle position – the aperture sight, if you will – could be your everyday sight, with a fine bead (down in the notch) and the coarse bead (between the ears) reserved for targets very close or very far away.

A common complaint about the buckhorn is that the large ears block the light, making it difficult to pull the bead down into the notch where, we assume, it belongs. As a result, in the heat of the moment hunters have the bead too high when they pull the trigger and shoot over their target.

But what if that was the designers’ intention all along? It is well known that an object is automatically centered in the area of greatest light, and this is the principle behind all aperture sights. Suppose, long before William Lyman discovered this in the 1890s and designed his tang sight to accommodate it, that the buckhorn was intended to function exactly the same way, except farther out along the barrel?

If so, then later modifications in which the full buckhorn was slimmed, trimmed and shortened only eliminated its functional advantages while retaining most of its loudly condemned disadvantages.

These days, when someone acquires an old rifle, the usual first move is to replace the “out-moded open sights” with something better. Sometimes this is a scope, other times a Lyman or Redfield receiver or tang sight. Almost anything is considered better than the old Rocky Mountain buckhorn. Quite often, though, attempts to improve the sights impair the rifle’s other qualities, such as ease of carrying, or quickness to get on target. Learning to use the buckhorn sight as outlined above just might be a better answer.