Prewar Model 70 .257 Roberts

A Favorite Cartridge for Western Hunting

feature By: John Barsness | November, 20

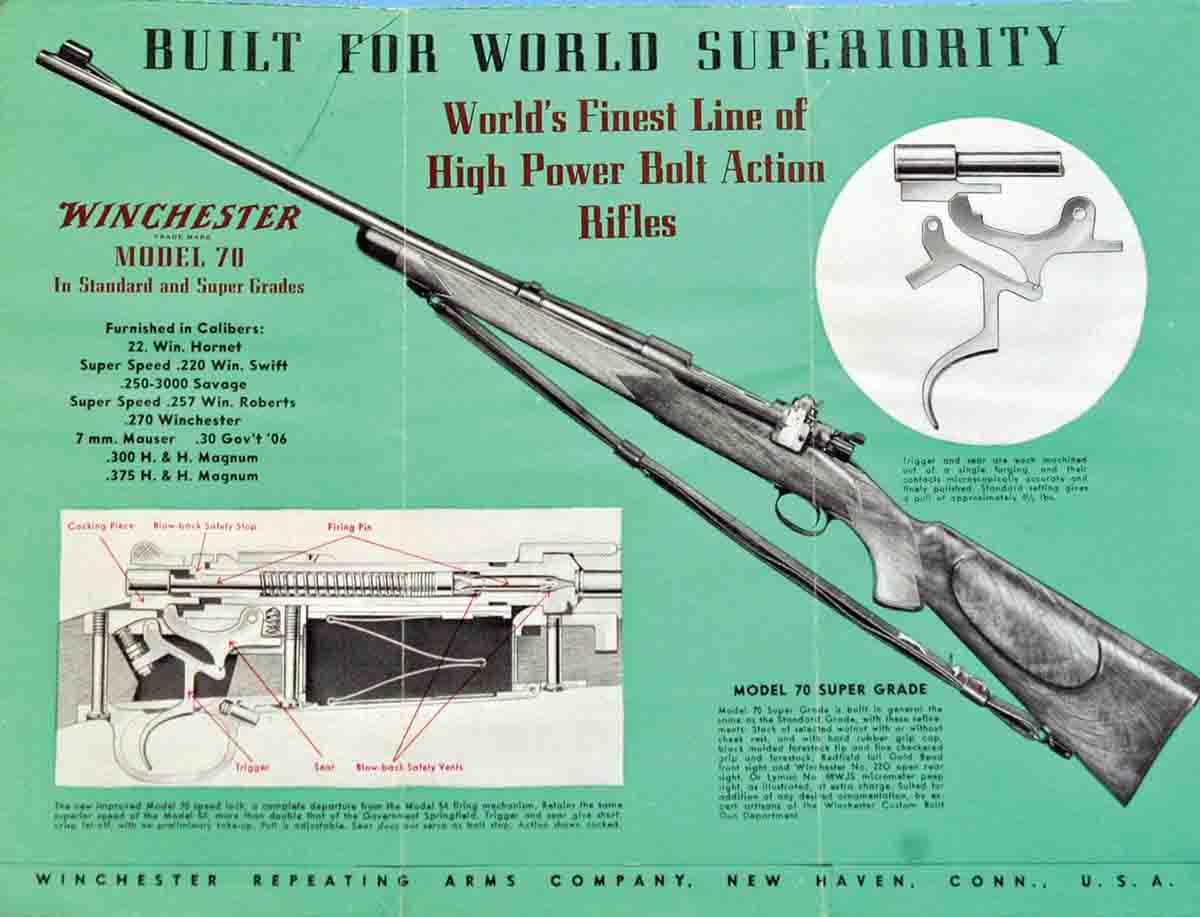

My copy of the brochure came from an ad on an internet site, purchased because of also recently purchasing a very early Model 70 in .257 Roberts. The rifle’s serial number indicated it was made in 1936 – to build up inventory before the public announcement.

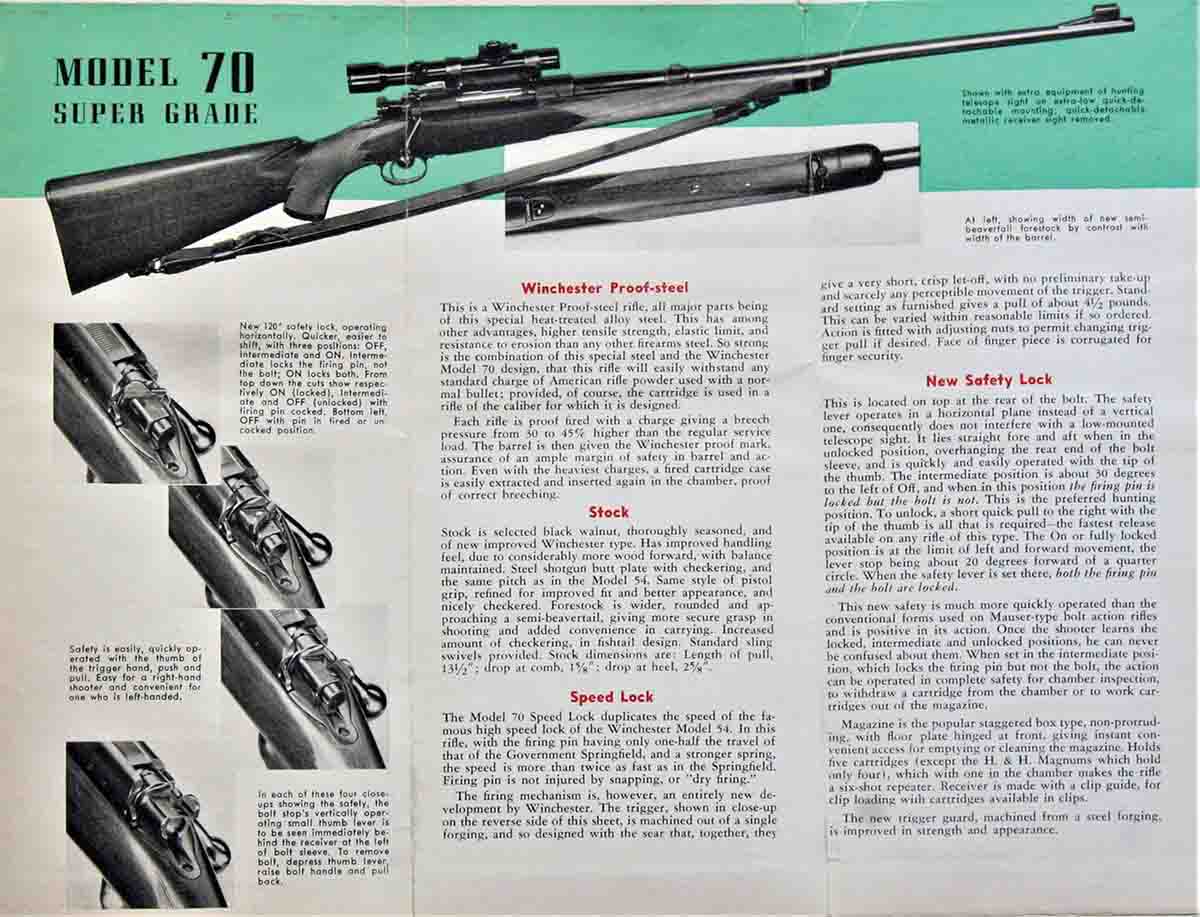

Luckily for me, minor changes had been made to the .257 after it left the factory, most importantly three extra holes for 6-48 screws. “Prewar” Model 70 actions, made before production was suspended in 1942, had two 6-48 holes on the left side, near the rear, for receiver sights – or a rear scope base (not an uncommon arrangement in those days). There were two more holes on top of the action ring for a front scope base, or the rear mounting block for one of the era’s long target scopes.

Back then, many front target-scope blocks were designed to fit the rear-sight slots of rifles, but apparently an early owner preferred a screwed-in front block, since two precise holes were drilled just in front of the sight slot (filled by a steel blank with “Marbles Gladstone Mich USA” stamped in tiny letters). A third extra hole was drilled in the action bridge to accommodate the one-piece Redfield base and rings that came with the rifle. Due to the extra screw holes and missing rear sight, the asking price was about half of an unaltered prewar .257 in the same condition – meaning I could afford it.

My library of firearms literature includes several books published during the decade after the Model 70 appeared, and three contained specific reviews of the new rifle. The earliest appeared in 1937, in Philip B. Sharpe’s The Rifle in America:

“[The safety] is by no means an ideal proposition and happens to be this author’s only criticism . . . It is so designed that when a telescope sight is mounted low on the receiver [the safety] is extremely difficult to reach . . . The mechanism . . . retracts the firing pin so there is no pressure on the sear. At the same time it locks the bolt handle. In the 45-degree [middle] position the firing pin is still locked but the bolt can be opened. Many a shooter, including this author, carries [the] rifle in the 45-degree position. It is easy to snap off with the thumb . . . with a motion similar . . . to cocking an ordinary hammer rifle.”

This resembles the “backward” motion of the safeties on CZ rifles, which so many American shooters criticized that CZ changed its centerfire safeties some years ago. More recently, it also made the safety of the new 457 rimfire rifle a “push-forward.”

The two other reviews never mentioned this backward motion, but agreed the safety was not as scope-friendly as the brochure claimed.

The prewar safety operated on the left side of the cocking piece. After the war, Winchester’s first change was to move the lever to the right side, making the release a push-forward design. The new lever, however, was slightly larger than the original, thus failing to solve the low-mounted scope problem. In 1948, Winchester changed the lever’s shape to the one still used on Model 70s today, a low horizontal bar on top of the cocking piece with a vertical thumb-knob below.

The only other negative criticism came from Keith: “The 98 Mauser action is my personal preference in a modern bolt action . . . The [Mauser] will handle gas from a punctured or defective primer better than any bolt action I have used . . . And more important, there is an integral ring inside of the receiver that greatly strengthens the weakest portion of a bolt action. The barrel diameter covers the entire rimless cartridge case, right up to the extractor cut . . . The Winchester Model 70 action is made of the finest steel and is perfect in most details [but] will not handle a possible gas-escape as well as the Mauser . . .”

In fact, the pre-’64 Model 70 action has almost no provision for gas escape, the tiny exception is a small port drilled into the right side of the receiver ring. Stuart Otteson, in his 1976 book The Bolt Action, A Design Analysis, described the 70’s poor gas-handling in detail, but also stated that while the slick-feeding “coned” breech leaves more of the case head unsupported than the Mauser 98 system, “It has proven adequate through decades of hard use.”

Other than Keith’s criticism, the three reviews praised the new Winchester highly, with Keith particularly liking the stock-bedding system: “The Model 70’s three guard screws and forward forearm screw combine to bind the action, stock and barrel into a stiff assembly that insures a super-accurate rifle . . . ‘floating’ barrels . . . are simply a cheap substitute for proper wood and perfect bedding . . . any rifle actions are very difficult to keep in the stock . . . When the forend is anchored to the barrel . . . there is much less chance of the metal kicking back through the stock. I have never seen a Model 70 stock so split, which speaks mighty well for the system of guard screws and barrel screw.” Today, of course, we know that Keith was wrong about the accuracy potential of free-floated barrels, but when all rifle stocks were made of wood, and epoxy-bedding remained a few years in the future, he was at least partly right, especially concerning hard-kicking rifles.

The contemporary Model 70 reviews made me curious about the early reaction to the .257 Roberts as well, partly because of hunting with several .257s over many years, especially the Remington 722 inherited from my paternal grandmother. The .257 apparently became pretty popular both before World War II and afterward – until the .243 Winchester appeared in 1955.

The .243 immediately started taking the place of the .257 for two reasons. First, it appeared in the Featherweight version of the Model 70, which was considerably lighter than any prewar ’70. This appealed to a lot of hunters, especially those who’d recently hiked considerable distances with a 10-pound M1 Garand. My “standard” weight Model 70 .257 weighs 8 pounds, 3 ounces without a scope and mounts, and just about 10 with a 3-9x 40mm Burris Fullfield II, five rounds in the magazine and a leather sling. Remington’s prewar bolt action, the Model 30, was just as heavy, and even the postwar Remington 722 was somewhat heavier than the Model 70 Featherweight.

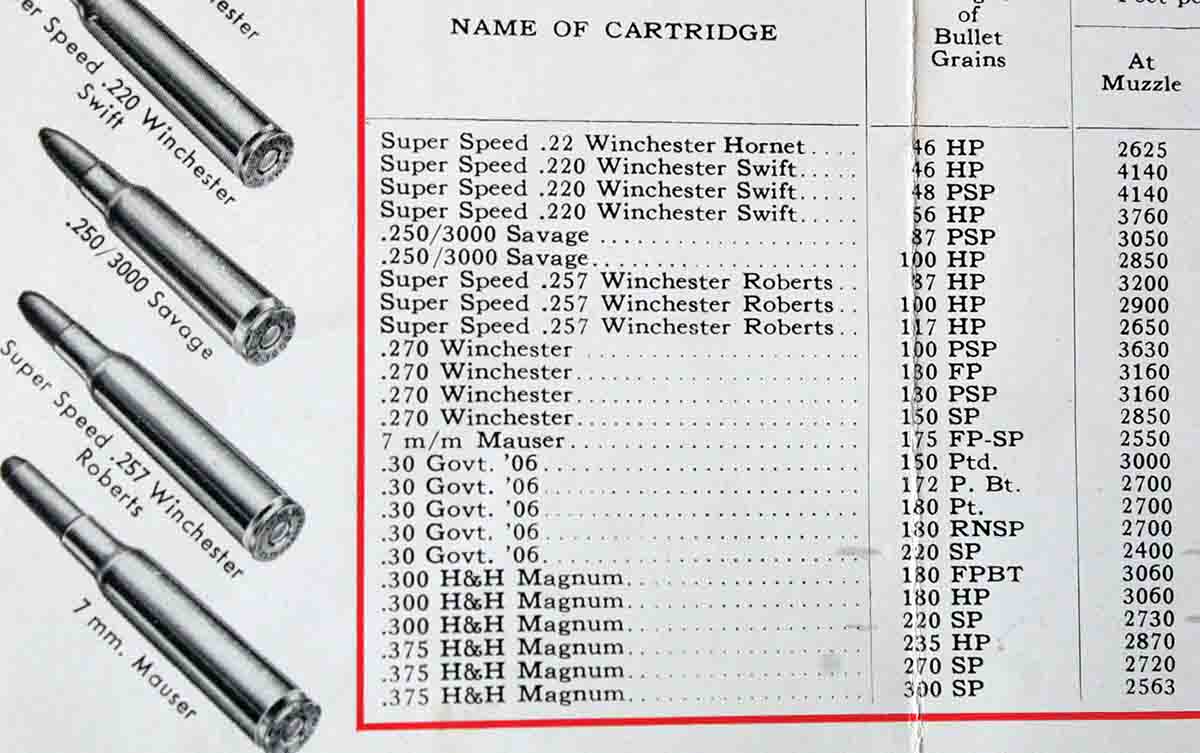

Also, the original velocity for the 100-grain .243 factory load was listed as 3,070 fps, 170 fps faster than 100-grain .257 ammunition from Remington and Winchester, and the 80-grain .243 varmint load was listed at 3,500 fps, 300 fps faster than Winchester’s 87-grain .257 load. (Early .243 ammunition, however, was chronographed in 26-inch barrels – a common practice back then – and did not achieve anywhere near the published velocities in the 22-inch barrel of the Model 70 Featherweight, or the Winchester Model 88 lever action, which also appeared in 1955. My 1964 Speer reloading manual contains a list of factory ammunition chronographed in typical hunting rifles. From the 22-inch barrel of a Model 88, 100-grain .243 ammunition from Federal, Remington and Winchester chronographed around 2,900 to 2,950 fps.

Two factors apparently reduced the .257’s original velocity potential. First, Ned Roberts had found relatively mild velocities resulted in finer accuracy in his .25 wildcat, probably due to the powders and bullets of the day. (Roberts once stated that he never found a spitzer that shot accurately in the .25 Roberts.)

My search for early IMR-4350 .257 loading data turned up some from Ned Roberts himself, in his 1947 book Big Game Hunting:

“. . . we can handload the [.257 Roberts] with 48 grains weight of DuPont I.M.R. #4350 powder and the 100-grain…bullet to give 3400 ft. sec. of velocity. The cartridge hand-loaded with 47 grains I.M.R. #4350 . . . and 117-grain . . . bullets gives 3,000 ft. sec. muzzle velocity.”

Roberts does not mention the barrel length of the rifle, but it must have been long to get 3,400 fps with a 100-grain bullet. While IMR-4350 has changed slightly since 1940, I have been loading 100-grain bullets in the .257 with it since the early 1980s. At first, I worked up a relatively mild load for Eileen when she started big-game hunting, using 45 grains with the 100-grain Nosler Partition for just over 3,000 fps from the 24-inch barrel of my Remington 722. Soon, however, Eileen switched to the .270 Winchester, and I started using the 722 for my deer and pronghorn hunting, working up to 48.5 grains of IMR-4350 for around 3,250 fps and even better accuracy.

This may seem like an “overload,” but Hodgdon’s .257 data for IMR-4350 lists a maximum of 47.7 grains with the 100-grain Speer boat-tail, for 3,077 fps, also from a 24-inch barrel, at 47,000 copper units of pressure (CUP), which is 3,000 CUP less than the Sporting Arms, and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute maximum CUP for the .30-06. I never had the slightest problem with the 48.5-grain charge in temperatures from below zero to 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

However, when shooting the prewar Model 70 the 100-grain handload was another I’ve used in older .257s in recent years, 46 grains of IMR-4350 and the Barnes Tipped TSX, which got around 3,000 fps, still plenty for any deer in North America – or even elk. In 2014, Eileen used a slightly warmer load in her New Ultra Light Arms .257 to instantly drop a medium-sized cow elk.

Older editions of Cartridges of the World also contain some interesting IMR-4350 data. Author Frank C. Barnes noted: “The 257 is much underloaded by the ammunition companies, and the factory ballistics do not indicate its full potential. With the 117- or 120-grain boattail bullet, at velocities of around 2,800 fps…such loads have been used very successfully on elk and caribou. The author has used it for many years and it is one of his favorite calibers for western hunting.”

Another of my favorite .257 loads is 45 grains of IMR-4350 and the 115-grain Nosler Partition, which I would not hesitate to use on caribou or elk. Hodgdon lists 45.5 grains as maximum with the same bullet for 2,866 fps at 46,600 CUP, but in several of my .257s it has been a little faster. In the Model 70 it averaged 2,950 fps over a chronograph 15 feet from the muzzle.

While some companies do not offer any .257 Roberts ammunition anymore, there’s still plenty available, though it is relatively expensive. The cheapest I could find on the internet ran around $35 per box, and some over $60. However, quite a bit is +P, with muzzle velocities listed at 3,000, or close to it, for 110/117-grain bullets. I found some new Hornady and Nosler ammunition on local shelves, so tried them in the Model 70 as well.

I did not alter the factory bedding, and tightened the barrel screw as much as the front and rear action screws, partly because my most accurate pre-’64 Model 70 was a .30-06 that shot cloverleafs with the forend screw tight. Range testing turned out to be quite comfortable due to the rifle’s weight. If I ever hunt with it, a lighter scope might get mounted, though at 13 ounces the Burris is by no means a heavyweight. No wonder Winchester introduced the Featherweight in the 1950s – though the company never chambered it in .257 Roberts.

.jpg)