Walnut Hill

Form, Function and (Perfect) Form

column By: Terry Wieland | November, 20

In 1896, an American architect framed a rule of design that was to have an extraordinary influence, its effects felt to this day in almost every corner of life.

“Form ever follows function,” is an excerpt from a longer quotation by Louis Sullivan, known as the “father of the skyscraper,” and just as skyscrapers have taken many forms – some beautiful, like the Chrysler Building, others astonishingly ugly – so his most famous quote has been taken out of context, exaggerated, distorted and used to justify some truly grotesque creations – architectural, mechanical and otherwise.

For a rifle, the original words are certainly valid, but the sentiment can be extended to read “form follows function, but perfect function follows perfect form.”

The fact is forgotten that Sullivan drew his inspiration from a Roman architect, Vitruvius, who wrote the first textbook on architecture in the first-century BC. Vitruvius was an artillery officer in the Roman army, concerned with the design of early siege weapons like ballistas and catapults. His design theories applied to both artillery and buildings, and stated that the latter should have three attributes: They must be solid, useful and beautiful. The latter – beauty – is the feature most often dismissed in modern design.

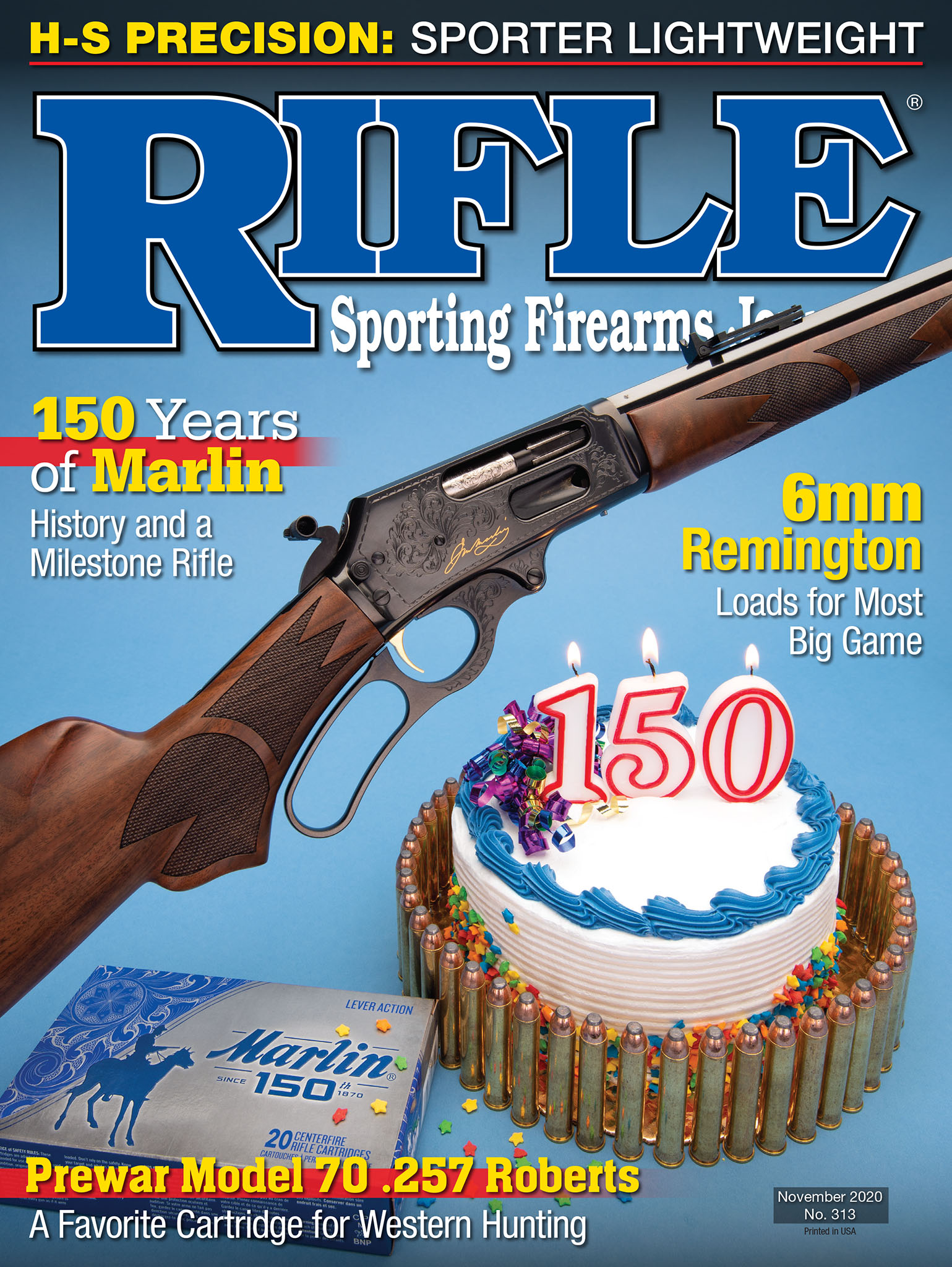

Looking back over the past 150 years or so, the most successful rifles have been those that were not only sturdy and useful, but notably racy in their styling. The Winchester 92 is a good example, as is the Savage 99. Of course, not all 92s were wonderful, nor all 99s, but the basic elements were there. Another good example is the 1903 Mannlicher-Schönauer. In each case, you can pick out particular design elements geared to the rifle’s intended use. Its flat sides, devoid of projections, make the 92 an ideal saddle scabbard rifle, while the Mannlicher’s “butter-knife” bolt handle is safely out of the way, unlikely either to dig into one’s ribs or pop open when scaling the Alps hunting chamois.

In the world of handguns, the two most beautiful ever designed are the Colt Peacemaker and the German Luger. It’s no coincidence that they are also two of the longest-lived, and unarguably the two most-collected handguns in history.

Outside the realm of firearms, one area where function would presumably be all-important, and beauty negligible, is in the design of fighter aircraft. Yet, if you look back to 1940, one of the most effective of all fighters in World War II, and arguably the greatest of them all, Britain’s Supermarine Spitfire, also happened to be one of the most stylish and beautiful. This was not coincidence. It was the classic example of perfect function following perfect form.

Marek Reichman, the director of design for Aston Martin, noted that, “The Spitfire wasn’t designed for its looks, but the engineers understood that what works looks right. It’s simplicity and great engineering.”

Probably nowhere in the car world has this principle been adhered to as it has at Aston Martin. Its cars have been around since 1913, have won races everywhere and denote the best in taste to those lucky enough to own one. More than any other, the Aston Martin is known as James Bond’s car, just as the Walther PPK is his pistol.

At times, gun designers have attempted to apply “form follows function” to the exclusion of all else, and have designed some genuine monstrosities. Not a rifle but a shotgun, the Ljutic Space Gun of the 1980s resembled a blowpipe with a couple of handles sticking out at right angles. It was a trap gun with no application to any other type of shooting. Considering that it looked like it was turned out on a lathe, with a side trip or two to a milling machine, and a total cost of materials that could not be more than $50, the Ljutic was expensive: In 1985, it cost $3,495 – the same as Ljutic’s beautifully made, conventional, single-barrel trap gun, and more than twice as much as a Beretta Model 680.

Louis Sullivan’s original statement about form and function read, in full, as follows: “It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human, and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.”

Sullivan was referring to natural law, and recognizing that while any man-made object from skyscraper to space gun can consist of straight lines, hard corners and right angles, the human body does not. Some gunmakers have tried to force users to adapt to poor designs, but the most successful have been those who, conversely, adapted their designs to the human body.

The riflemaker’s task is made considerably easier if a rifle has only one purpose. A target rifle, for example, is intended to consistently punch holes in paper. Modern benchrest rifles and century-old German Schützens are both target rifles, but they could hardly be less alike. The difference is, the Schützen must be accommodated by the shooter’s body with no other support, while the benchrest seeks to support the rifle independent of the human body as much as possible. Looking at both the modern “unlimited” benchrest rifle and an 1890’s Schützen, the uninitiated would never guess their intended purpose is virtually the same: punching holes in a distant target.

Obviously, form and function are closely related to the recent science of ergonomics, but the latter is not very well understood. Some modern rifles, adhering more or less to the basic AR style, have been described as “ergonomic” by the same crowd of non-shooting flacks who write most press releases, and drop in words like “cult” and “ethical” with no idea what they mean in the context of hunting and shooting.

Apparently, a rifle is now considered “ergonomic” if you can manage to shoot it without incurring actual bodily harm. That’s a far cry from the original meaning, which can be summed up as a tool possessing design qualities that make it a pleasure to use.

How many of these new rifles really are an actual pleasure to use? Very few. With their angular collapsing stocks and spring-loaded bipods, sprouting saw-toothed Picatinny rails in every direction, they scrape knuckles, bruise cheeks, pinch shoulder muscles, slash the upholstery in your car and gouge you every place they touch if you’re forced to lug them around on a sling.

Accurate they may be, powerful they may be, but ergonomic they’re not. Ultimately, I expect most will be as short-lived and forgettable as the Ljutic Space Gun, regarded 40 years later as little more than a curiosity, and an ugly one at that.