Steyr Zephyr II .22 Long Rifle

A Refreshing Breeze from Austria

feature By: Terry Wieland | November, 18

Unfortunately, “serious, high-quality” .22 rifles are not easy to come by. They used to be, if memory serves, but not any more. Today, the typical .22 rifle is too small, too light and too cheap. Over the past 75 years, the .22 rimfire has gradually evolved into a rifle for kids without much money – hence the reduced dimensions and weight, the emphasis on its ability to take abuse and still function and, above all, to be sold at a price the proverbial “farm boy” can raise from selling eggs. (One notable exception is the Ruger 77/22, but as with many things from Ruger, it is the laudable exception that proves the rule.)

This is not intended to be a stroll down memory lane, remembering things that used to be. All too often, the great things we think we remember actually never were. Not every .22 made in 1920 was a masterpiece of the gunmaker’s art. Rather, think of this as an object lesson, and to that end I present Exhibit A: The Kimber Model 82.

As .22 rifles became progressively tackier through the tasteless and misguided 1970s, cries went up in the shooting media for a real .22 rifle, for real riflemen, made “the way they used to be” – blued steel and oiled walnut with adjustable sights, a light and responsive trigger and a bore that might have been hand-cut by Harry Pope. The then-new company, Kimber of Oregon, responded in 1980 with its Model 82, a rifle that was a real gem.

Unfortunately, that was near the high-water mark of the inflationary era that started with the 1975 oil-price hikes. The Model 82, with its select walnut “American classic” stock and finely blued steel, sold for upward of $400 – about the same as a Weatherby Mark V. Every one of my gun-loving friends wanted one, but not one of us bought one. The Kimber Model 82 disappeared after about 10 years.

This, alas, is typical of what happens when a manufacturer responds to the demands of the gun-loving few and offers an expensive rifle to the penny-pinching many. It goes nowhere, albeit accompanied by tears and sobs.

Aesthetics aside, such fine rifles are made to last. There is absolutely no reason a good .22 made today should not still be shooting a century from now. When I was a kid, my first .22 was a single shot my father bought as a teenager in the 1930s. Made by Cooey, a Canadian company later acquired by Winchester, it was a bolt action with open sights and no provision for a scope. The barrel was steel, and the stock was genuine American walnut – as I learned when I sanded it down to refinish it and encountered the unmistakable scent of freshly cut walnut for the first time. In a misguided moment, I parted with that rifle, having moved on to – I thought – better things. Little did I know I would later struggle to find something as good to take its place.

That lingering regret partly accounts for my eagerness to get my hands on the new Steyr Mannlicher Zephyr II, successor to the original Zephyr from the 1960s. My high regard for Steyr is comparable to my feeling for Belgium’s FN as makers of fine firearms of all types – beautifully made and following long tradition by people who care.

Steyr Mannlicher dates from 1864 and has long experience producing high-quality .22s. As chief armsmaker to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and later to the state of Austria, Steyr designed and manufactured military weapons of all kinds. Included on that list were military-style rifles chambered in .22 rimfire for training and practice – virtually identical to the real thing except for caliber. Steyr also made Olympic-level match rifles and everything in between. In the 1930s Steyr produced .22 hunting rifles of a quality comparable to their legendary Mannlicher-Schönauers.

The postwar Zephyr, which was made from 1955 to 1971, was a conventional turn-bolt .22 with a detachable box magazine and double-set triggers. It was not listed in the Stoeger catalog (Steyr’s long-time importer) nor in Gun Digest magazines from that period. However, Stoeger did import a rimfire carbine with the usual Mannlicher stock, billed as a custom item that retailed for about $125 – a substantial sum in 1961.

The Zephyr was one of the casualties of the economic turmoil that spelled the end for so many fine imported guns in the early 1970s. For the next couple of decades Steyr (like other European manufacturers) struggled to match American tastes with economic realities, and rarely did the twain meet. This was especially true in the case of the .22 rimfire.

Exactly what catalyst moved Steyr to revisit, redesign and reintroduce the Zephyr is a secret that remains locked in the breasts of the gunmaking gnomes of Austria. The new rifle is the Zephyr II, and while its lineage is apparent in some ways, such as the basic quality, in other ways it is quite different. The original Zephyr was old-fashioned; the new Zephyr is thoroughly modern, but only in good ways. While there are some features I could live without, overall it lives up to its name. It is a breath of fresh air.

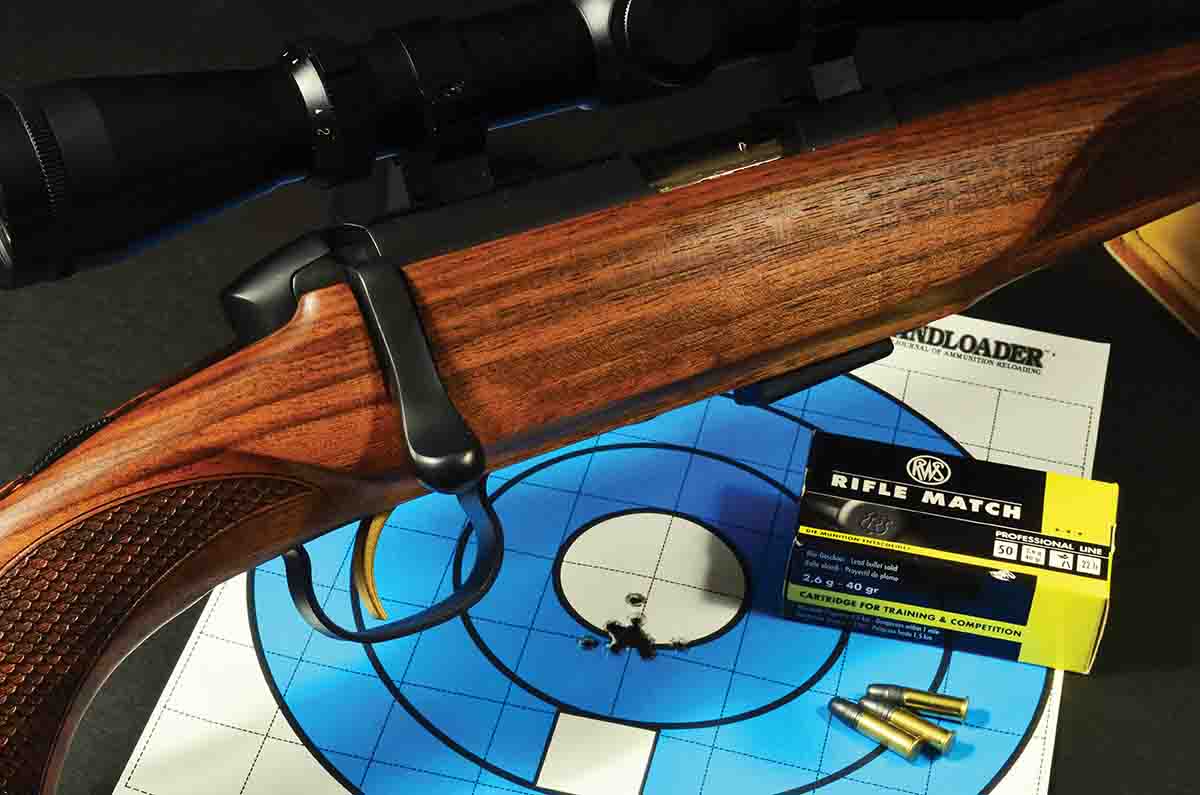

The stock is nice walnut in a vaguely American Classic style with European touches that might better be termed “Euro-Modern.” It is straight (i.e., with little drop at the heel), combining a pistol grip with a sculpted Bavarian-style cheekpiece and Schnabel forend. Instead of checkering it has a fish-scale pattern (undoubtedly laser-cut) that provides an excellent gripping surface.

The removable clip is made of polymer – similar to that used in rifles like the Blasers and Sauers. It is interchangeable with nearly identical clips for the CZ rimfire rifles, and these are available in steel and polymer and both five- and 10-round capacity. Those billed as CZ clips cost about half the price of those billed as Steyr. Whether it was designed by CZ, Steyr or an independent third company, who knows? Whichever, it means that additional clips are available for modest prices, which is always a big plus. Functionally, they gave no trouble whatever – another big plus.

(Incidentally, the Zephyr II is also available in .17 HMR and .22 WMR. A test rifle sent to my editor in .17 HMR performed very similarly to my .22 Long Rifle – in other words, beautifully.)

What are the features I can live without? The forend is one. While I admire Schnabels immensely, in cross-section the forend is V-shaped, and while the fish-scale carving does give a good grip, I always felt as if my hand was about to slip off. Another concerns the guard screws. There are three – two actual guard screws and one wood screw that retains the trigger bow behind the trigger. This arrangement is hauntingly reminiscent of the old Mannlicher-Schönauers, and there is nothing wrong with that. However, these are Torx-head screws, and each comes disguised by a little polymer cap that presses into place. The caps are easily removed with a fingernail to give access to the screw head, and the pessimist in me wonders how long it would be, with the rifle in actual use, before they got lost. I suspect not long.

The rifle comes with integral dovetails for scope mounting, and while this is a proven system of undoubtable virtues, it presents the problem of finding suitable scope rings if you want their quality and appearance to match the rifle.

Try as I might, I can’t find anything else to complain about. At a suggested retail price of $995, the Zephyr II is certainly an investment, but it’s a rifle your descendants could be using a century from now.

The obvious question with any rifle is accuracy. A .22 rimfire is a different animal from a typical big-game rifle, with different standards of acceptable accuracy. It seems to me, however, that placing bullets close together, shot after shot, is even more important with a .22 intended for any serious use. It is not unusual to go out and burn up a box of 50 rounds at a sitting.

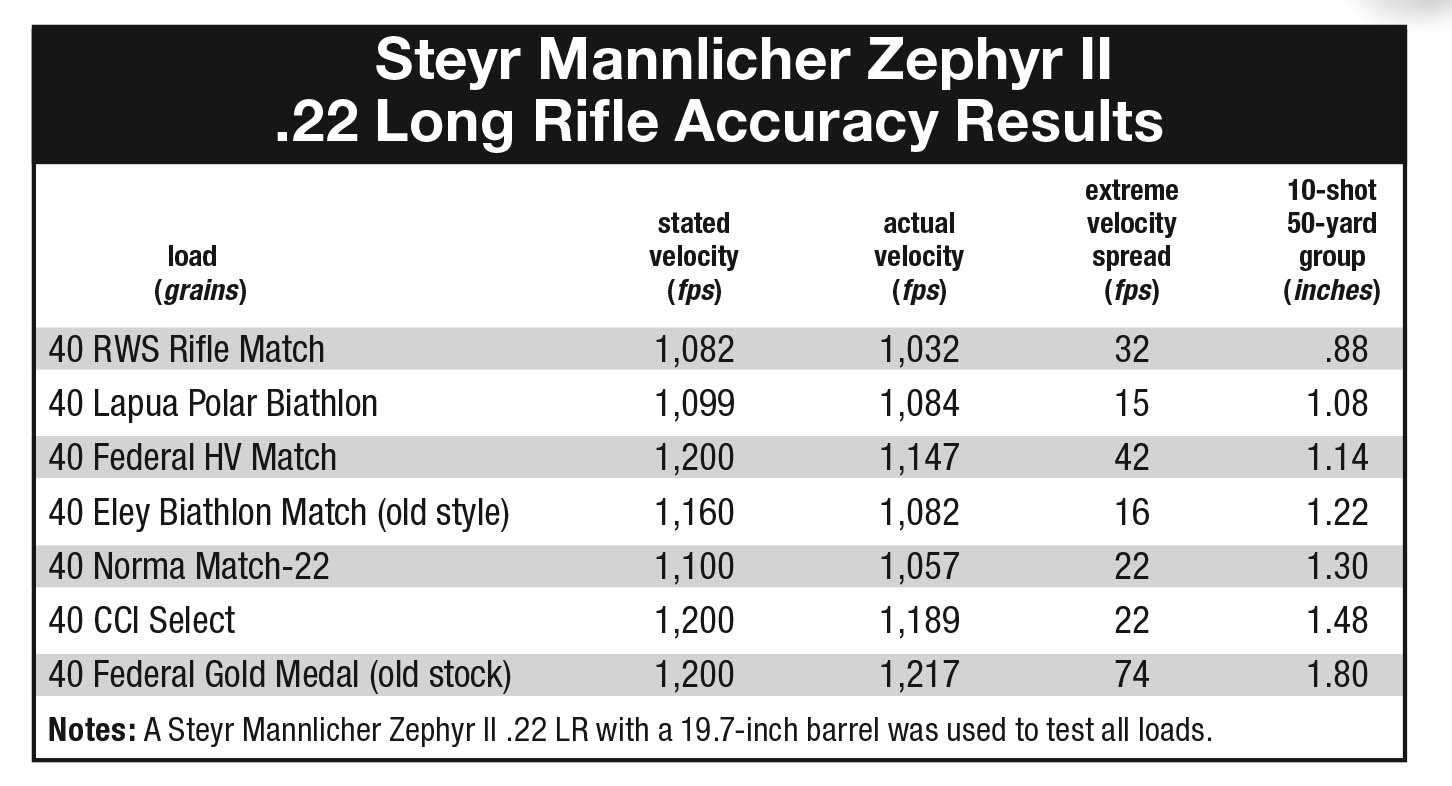

I gathered together a half-dozen different types of high-quality match and target ammunition from Norma, RWS, Federal, Lapua and CCI, and shot a 10-shot group with each at 50 yards. The results are shown in the accompanying table.

The Zephyr II sailed through with flying colors, and I can almost imagine myself creeping through the uncut hay with it in search of woodchucks. For my boyhood self, it would have been a dream come true.