The First .308 Winchester

Shooting an Early Model 70 Featehrweight

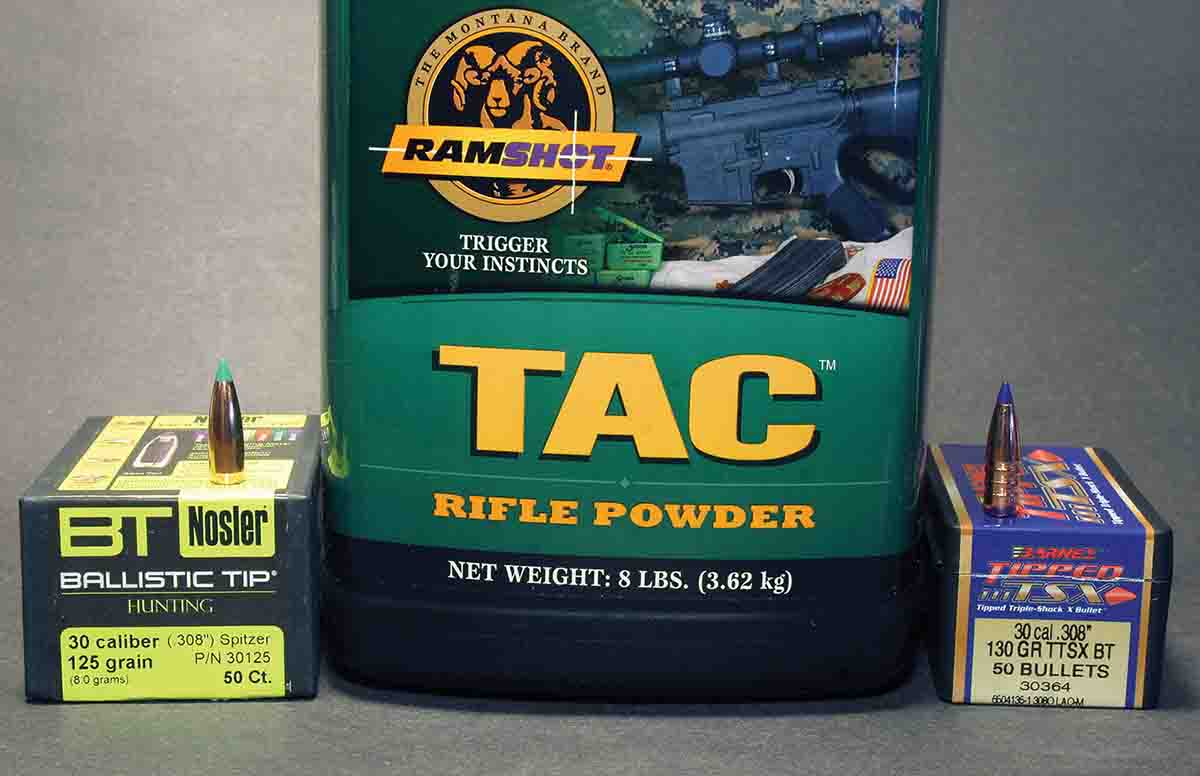

feature By: John Barsness | November, 18

In 1952, however, the shooting industry worked comparatively slower, partly because the major monthly gun magazine in the U.S. was American Rifleman, sent to members of the National Rifle Association. The existence of Winchester’s new rifle was not acknowledged until the 1952 September issue, with four paragraphs in the “Dope Bag” section, probably written by Technical Editor Julian Hatcher and accompanied by a black-and-white photo of the three initial .308 factory loads next to a .30-06 cartridge:

“The Arms and Ammunition Division of Olin Industries has announced a new short sporting cartridge to be called the .308 Winchester. As a companion for the new cartridge, the famous M/70 Winchester bolt-action rifle has been reduced to 6.5 pounds weight. This weight reduction is accomplished by stock redesign, a new 22-inch barrel contour, aluminum buttplate, trigger guard and floorplate.

“The new .308 Winchester cartridge is a full half-inch shorter and 10 percent lighter than the standard .30’06, and is stated by [its] maker to have higher velocities and energies than any other sporting cartridge of similar size and weight. The cartridge is an outgrowth of the new, lightweight T-65, caliber .30 military cartridge which was announced in the February Rifleman. It utilizes the high-density, high-energy, and controlled burning rate of ball powder which was first used in the U.S. carbine caliber .30 M1. It will be manufactured in the 150- and 180-grain Silvertip controlled expanding game bullets and in the 110-grain soft-point for varmint and pest shooting.

“The new Featherweight Model 70 is equipped with sling swivels, open rear sights, and metal bead front sight. It features a free-floating barrel.

“The receiver is drilled and tapped for all conventional receiver sights and telescope sight top mounts and the new high comb stock is optional. A 24-inch barrel may be obtained on the Featherweight on special order.”

Waite mentioned the “full floating” barrel, but noted “the right side of the stock bore rather heavily against the side of the barrel . . . We probably should have scraped away all stock wood touching the barrel on the right side but we decided against doing this just to see what would happen.”

Waite mounted a 12x Unertl scope with the front mount in the rear sight slot, a common arrangement back then. The range test consisted of five-shot groups with the three factory loads, with the barrel allowed to cool between groups. With the exception of several “fliers,” the groups measured 1.5 to 4 inches, with most measuring 2.25 to 3.0 inches.

He stated the rifle weighed 7 pounds before mounting the scope, not the advertised 6.5 pounds, though he didn’t list the scale used. I searched several following years of American Rifleman but never did find a follow-up report on the Featherweight with a relieved forend channel.

This research took place after finding a pre-’64 Featherweight .308 on the used rack at Capital Sports & Western Wear in Helena, Montana. I had previously owned about a dozen pre-’64 Model 70s, including another Featherweight in .30-06, a pre-World War II “standard” .30-06 and postwar standard rifles in calibers from .257 Roberts to .300 H&H Magnum. After those other Model 70s and hunting big game with various cartridges around the world, I had concluded that a Featherweight .308 would be ideal as an all-around pre-’64. Luckily, the rifle at Capital Sports had enough field dings to take hunting without worries – or decreasing my bank account too much.

The .308 Winchester was the Featherweight’s only chambering through 1954, and according to its serial number, mine left the factory early in ’54. Winchester did not chamber the small-but-mighty .308 in any other rifle until 1955’s Model 88 lever action, the year the company also started chambering the Featherweight in .270 Winchester, .30-06 and a pair of new .308-based cartridges, the .243 and .358 Winchesters.

Thanks to synthetic stocks, today’s hunters do not regard light bolt-action rifles as revolutionary, but they were unusual in 1952. Despite the popularity of light lever actions such as the Model 94 Winchester carbine (a genuine 6.5-pound rifle), many hunters thought bolt-action rifles should be heavier; otherwise they would only be accurate enough for “woods hunting.” Savage had introduced a light bolt rifle in 1920, naturally named the Model 20, but dropped it after 1930, partly because so many hunters (including several writing for hunting magazines) preferred heavier rifles.

This prejudice partly arose because most factory rifles had steel or hard plastic buttplates. In 1952 all Model 70s had steel buttplates – except for the Featherweight’s aluminum plate. Hard buttplates naturally tend to hurt shoulders, and back then recoil reduction was usually accomplished with a “properly” heavy rifle, or fitting a recoil pad.

Back then, solid rubber pads were only slightly softer than steel, but many shooters still hated their looks. Gunsmith and author Roy Dunlap summed up the general opinion in his big book Gunsmithing published in 1950: “Recoil pads should never be used except for rifles of very heavy recoil, or for injured persons or others not able to take normal recoil.” (Gunsmithing remains in print, and Internet users can even purchase a PDF version.)

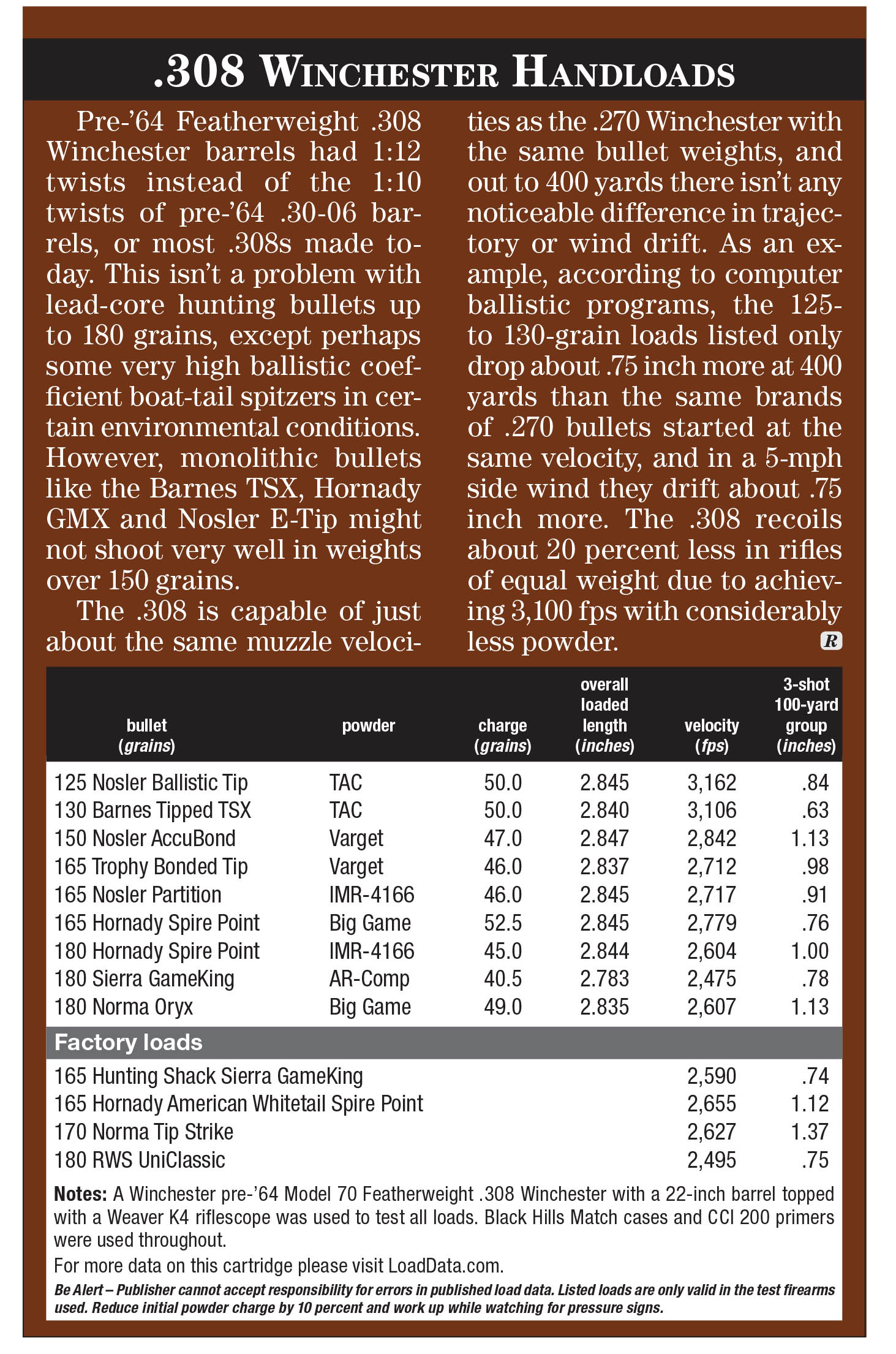

However, the Featherweight presented a third way to reduce recoil – using a lighter-recoiling, big-game cartridge – one reason the .308 soon became a standard chambering not only in American hunting rifles but around the world. Controlled-expansion bullets, from the pioneering Nosler Partition to various monolithics, make it even more effective, one reason my wife Eileen and I have used the .308 to take a bunch of big-game animals up to around 750 pounds, some of them shot beyond 300 yards.

Yet the .308’s modest muzzle velocities do not overstress cup-and-core bullets, and more than one African professional hunter I know uses the .308 for culling meat animals. Most favor cup-and-core 180-grain bullets partly because ammunition and components are far more expensive in Africa. When hunting in South Africa with my PH friend Rob Klemp in 2007, we visited the big sporting goods store he owns in Kimberley. The bullet shelves held plenty of controlled-expansion designs, including a couple made in South Africa, but were dominated by the green boxes of Sierra GameKings and ProHunters – with prices comparable to Nosler Partitions in the U.S.

In a way, the .308 Winchester is the modern 7x57, both in Africa and Europe, due to its modest recoil and reliable performance with cup-and-core bullets. When hunting red deer in Norway in 1996 with several groups of hunters, none of my companions had a 6.5x55 while several carried .308s, and a gun store in Bergen, the closest city, had a literal barrel full of Remington 700 .308s.

Roger C. Rule’s invaluable book The Rifleman’s Rifle contains more minutiae on pre-’64 Model 70s than any other single source. It not only lists the numbers of Featherweights made in various chamberings, but it includes such details as the year aluminum buttplates were dropped in favor of plastic (1959), along with factory sights and stock styles. Many pre-’64 Model 70 changes occurred in 1952, perhaps more than during any other year, including a new high-comb, modestly styled Monte Carlo stock for scope sighting. Before World War II most hunters still used iron sights, but after the war scopes rapidly became standard, and the high comb helped.

My Featherweight has the high-comb stock, and I decided on mounting a period-correct steel-tube K4 Weaver scope made in El Paso, Texas. Weaver still offers its Detachable Top Mount rings. The drawers of my workshop held a few old El Paso-made rings, and the K4 and rings matched the era and the rifle’s wear.

In the 1950s many hunters preferred mounting scopes in detachable rings with “back-up” iron sights. The comb height on the Featherweight is just about right for the K4 in low Weavers, but with firm cheek pressure the factory iron sights also work thanks in part to the “trough” in the middle of the bases.

Through 1954, Featherweights with Monte Carlo stocks came from the factory with a Marble’s No. 69 folding leaf rear sight and a bead front sight on a ramp. Per usual on hunting rifles, the front-sight hood is missing on my rifle, but in a minor miracle the factory sling swivels have not been replaced by studs.

A previous owner shortened the factory length of pull by a half inch but retained the aluminum buttplate. I can shoot the short stock comfortably because, unlike gun writers who are taller than they need to be, I’m close to average in height. However, a modern recoil pad might be in the rifle’s future, despite Roy Dunlap’s opinion.

Without a scope and mounts, the rifle weighs 6 pounds, 13 ounces, perhaps an ounce lighter than it would have weighed before shortening. (With the Weaver scope and a light leather sling it weighs 7 pounds, 9 ounces.) Wood varies in density, the reason walnut-stocked rifles can vary from the advertised weight. The 1955 Gun Digest – the first edition mentioning the Featherweight and .308 – contains a photo of a Monte Carlo Featherweight sitting on a scale that reads 6.5 pounds.

I decided to range-test the rifle with the original bedding like M.D. Waite did in 1953, “just to see what would happen.” It shot much like his rifle, with some ammunition providing “good practical hunting accuracy” and others scattering bullets. Many groups put the second shot up to 2 inches high and right of the first shot, probably due to the forend touching the barrel unevenly.

While working up handloads, I also discovered that only roundnose bullets could be seated out far enough to touch the lands and still fit in the magazine. No pre-’64s ever had “short” actions, though some writers called Model 70s in shorter cartridges “short actions” because the magazine was blocked off to an appropriate length. In this rifle it is blocked off to the semi-standard 2.85 inches initiated with Remington’s Model 722 in 1947, and afterward adopted by almost all other manufacturers for short-action rifles.

Many handloaders assume it’s necessary to seat bullets near the lands, but many bullets shoot more accurately when seated considerably off the lands, especially today. In fact, one of the bullets tried in my handloads, the Sierra 180-grain GameKing, grouped better when seated considerably shorter than the magazine requires.

A Hawkeye borescope indicated the rifle had not been shot much, despite the obvious field wear. The lands of the nicely cut-rifled bore (typical of pre-’64s) were very even, unlike the lands of many factory rifles chambered quickly with unpiloted reamers, so I expected the rifle would shoot well.

Instead of scraping the barrel channel, I used a temporary bedding technique to test whether it would shoot better with a truly free-floated barrel. A plastic bread-bag tab was inserted between the stock and action just behind the recoil lug. This lifted the front of the action slightly, and the barrel even more.

It turned out that one tab was not enough. A free-floated barrel shouldn’t contact the forend channel as the barrel whips around during firing. To test rifles for sufficient clearance, I grab the forend tip and barrel together in my right hand and squeeze: If the barrel contacts the forend, it’s not floated enough – which proved to be the case with one plastic tab. Adding another did the trick.

During the next range session, almost all loads grouped three shots about an inch, with some much less, and the tendency for second shots to land high and right disappeared. I then retested the two most accurate loads with five-shot groups that all grouped into an inch or so. Apparently Mr. Waite was incorrect about the rear sight slot harming accuracy, at least in this rifle. (Five-shot groups, by the way, average about 1.5 times as large as three-shot groups and are a far better indication of a rifle’s consistent level of accuracy.)

Now my original .308 Winchester needs to go hunting.