Winchester's Unloved Baby

The Low Wall Gets No Respect - Not Enough Anyway

feature By: Terry Wieland | November, 21

Even James J. Grant, the most devoted of single- shot enthusiasts and author of five books on the subject between 1947 and 1992, never treated the Low Wall separately from its High Wall colleague. Nor did Frank de Haas (Single Shot Rifles and Actions, 1969) or Larry Wilson (Winchester - An American Legend, 1991).

Since Wilson’s book was the company’s official history, is it any wonder the Low Wall has received the short shrift – that is, when it has not been ignored completely?

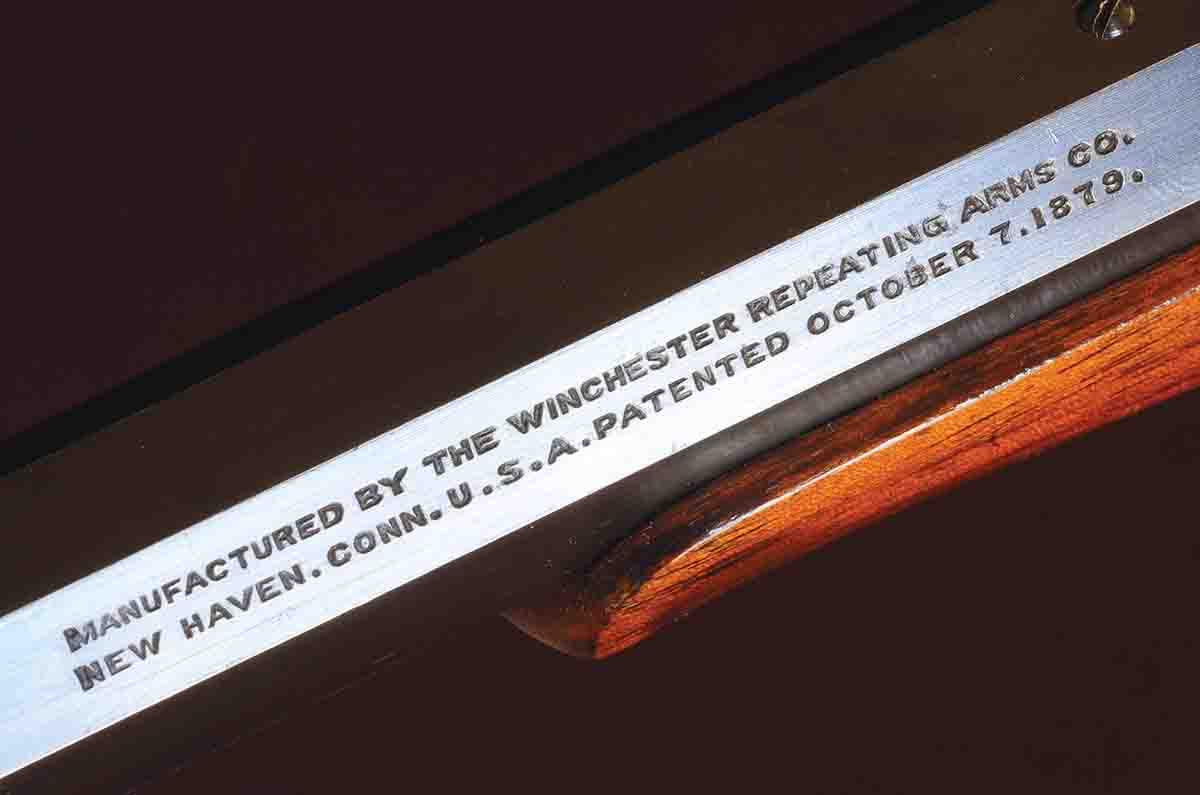

In 1885, Winchester purchased the rights to a single-shot rifle design from a young Utah gunmaker named John M. Browning. It was the beginning of a long and lucrative partnership. Winchester made some minor changes to Browning’s design before it went into production at the factory in New Haven, Connecticut. The first rifle appeared the following year.

The Model 1885, as it came to be known, was a falling block operated by an underlever with an exposed hammer. It was heavy, strong and proved to be very accurate and, although it came along too late to be a factor in the destruction of the great buffalo herds, it was to establish itself as one of America’s finest single-shot designs.

According to Grant, the Model 1885 was eventually chambered for at least 60 different rimmed cartridges, from the .22 Short all the way up to the .70-150 Express. Grant insists one special order rifle was made in .70-150, although this is disputed. The list even included the 20-gauge shotshell. The 1885 was later chambered for some rimless rounds as well, like the .30-06 and 7x57, so the number of known chamberings approaches 65.

It quickly became apparent that the high side walls supporting the breechblock got in the way when attempting to load tiny cartridges like the .22 Short. Someone came up with the idea of making it easier by milling away the highest parts of the walls to give more room.

James Grant wrote that he had spoken to two old-time barrel makers who claimed to have suggested this to Winchester, but added that he believed it was the Winchester engineers themselves who came up with the idea. Either way, within a year, the company had altered the action, milling away the high rear corners, and the first of what came to be known as the Low Wall appeared in 1887.

.jpg)

Internally, the two actions were identical, with interchangeable parts. However, while it was the early stages of the age of standardization through machine mass production, in the world of rifles it was also the golden age of options, customization and special orders. This was true of every American riflemaker, who all felt they had to offer dozens of choices in every aspect, from barrel length and configuration, to stock shape, lever designs and sights, to say nothing of ornamentation.

Grant himself did not realize the true extent of this, in the case of the Winchester Model 1885, until he discussed it with former Winchester executive Edwin Pugsley. In his third volume (Boys’ Single-Shot Rifles, 1967), he quoted Pugsley as saying that “Outside of the standard $12 sporting rifle and two or three models of .22 caliber muskets, just about all other Winchester single shots were special orders.” (My italics.)

Considering that between 1886 and the end of production in 1920, Winchester produced a total of 139,725 single shots, that is a lot of custom and special order rifles. Although most options and special order features could be had on either the High or Low Wall, one essential difference emerged very quickly: The Low Wall was threaded to take a smaller diameter barrel, and its chamberings were generally limited to rimfire cartridges and low-powered centerfires like the .32 WCF (.32-20).

Through the 1890s, there were three different configurations of the High Wall action (standard, thin-walled, and the heavier Express.) These were threaded to take three different sized barrel shanks, including the small one that fit the Low Wall. There were two identifiable Low Wall actions, but the common feature was that the Low Wall was thinner than the High Wall. These differences are not really material here, but it shows how many variations can be found, and how confusing the whole thing can be.

Beyond those differences, Winchester offered different grip types (straight and pistol); standard and set triggers, with two variations of the latter; different grades featuring special wood and engraving; different barrel configurations (round or octagonal) in different barrel lengths and weights.

Both were also available as take-downs, which necessitated an internal change. The original design called for a long leaf mainspring attached to the barrel. In order to make a take-down, this was changed to a coil spring around 1908, so there is the further delineation between leaf- and coil-spring actions.

James Grant, the lifelong collector, did not find a really high-grade Low Wall to illustrate in his books until volume three in 1967. Then, it was a beautifully engraved model in extremely fine condition. This gives some idea of the relative rarity.

Logically, then, high-grade and special order High Walls should be quite common today, but such is not the case.

After production ceased in 1920, it was followed by a 20-year frenzy of building custom varmint rifles for new hotshot cartridges like the .22 Hornet, .219 Zipper and 2R Lovell. The old single-shot actions were the favorite basis for these custom rifles, and the Winchester High Wall was one of the most desirable actions. As a result, many good original rifles were cannibalized for their parts. For that matter, more than a few full-blown deluxe Schützen rifles suffered the same fate, to the consternation of collectors like Grant.

No one can say for certain in absolute numbers, since no one knows what the original production numbers were to begin with, but the destruction of the more numerous High Walls resulted in more “factory original” Low Walls being available. Or so it seems from the rifles showing up in auction catalogs.

In 1969, Frank de Haas noted the relative dearth of original High Wall rifles available for customizing. He did not approve of destroying original rifles anyway, but observed that a lot of custom rifles, made in the 1920s to the 1940s, were coming on the market at that time. Not being original, these were of no interest to collectors, and most would-be custom owners wanted to build a rifle to their own specifications, not adopt someone else’s. As a result, these formerly high-dollar custom rifles could be had for relatively little money, with the actions then stripped out and redeployed.

There is a parallel here with the Stevens No. 44 and No. 44½ actions and rifles. The 44½, introduced around 1903 and produced until 1916, was the stronger and more modern of the two – some consider it the finest single-shot action ever made in the U.S. – so it was more desirable for building a custom rifle. Many 44½s, including very high grades, were torn apart for the purpose. The No. 44, good though it was (and is), was not strong enough to handle such cartridges as the .22 Hornet. As a result, they were left to grow old in peace, and today you will see more high-grade original 44s than 44½s.

The Low Wall went the other way. Rifles were lighter, more compact and handier. They generally had open sights or, at most, a tang sight like the Lyman and they were chambered for cartridges that could live quite happily with open or receiver sights, and did not demand long-range glass. As a result, the Low Wall makes a great “walking around” rifle, suitable for small game and varmints at reasonable ranges. In a .25-20, .32-20 or even a .38 Special, it’s a sweetheart. Grant shows one with a 15-inch barrel, chambered for the .44 WCF (.44-40). What its purpose would have been is anyone’s guess.

Not surprisingly, the move to make reproductions of older designs, which began in the 1970s, pretty much left the Low Wall behind. Although original manufacturers like Browning and Winchester, and Italian companies like Uberti, produced new High Walls of various descriptions, only Uberti made an early effort to build Low Walls. Winchester followed suit around 2000 and again in 2013, but both efforts were short-lived. As well, they were offered in some pretty hot cartridges, including various centerfire .22s and .17s, which really demand a scope to reach their potential, and the Low Wall simply does not lend itself to scope mounting. At least, not in my opinion, and if sales figures are anything to go by, not in the opinion of many others, either.

The upshot of all this is that original Winchester Low Wall rifles are relatively plentiful, and relatively inexpensive. A would-be collector who couldn’t possibly afford an array of Winchester ’73s can put together a respectable display of Low Walls for about what he’d expect to lay out for one ’73. They can be found in rimfire cartridges like the .22 Short and .22 Long Rifle, or in centerfires like the .25-20, .32-20 or .44-40, all of which can be handloaded with readily available brass and bullets, at least, in normal times.

What’s more, given the many blank spots in the history of the Winchester Model 1885, it’s a chance to do a lot of exploring.

Most of all – and this means something – the Low Walls are fun to shoot for anyone from a small child to an adult. They also provide a chance to shoot a fascinating piece of history without going broke in the process.