.275 Rigby Highland Stalker

Shooting the "British 7x57 Mauser"

feature By: John Barsness | May, 19

Rigby’s rebranding of the 7x57 took advantage of technological advances during the 15 years after the 7x57’s appearance in 1892. Before the .275, most 7x57 hunting ammunition featured traditional roundnose bullets weighing 170 to 175 grains loaded to a muzzle velocity around 2,300 fps, essentially duplicating the original 173-grain military load.

In 1903, however, Germany introduced a modernized military load for the 8x57 – the 7x57’s parent case – with a 152-grain spitzer (pointed) bullet at 2,880 fps, flattening trajectory enormously over the original 2,200 fps, 225-grain roundnose load. Many other countries soon followed Germany’s lead, including America’s military; in 1906, the U.S. Army changed the original 220-grain roundnose bullet loaded in the 1903 Springfield to a 150-grain spitzer.

Rigby similarly modernized the .275 for sporting purposes, loading both solid and “expanding” 140-grain spitzer bullets for the No. 2 High Velocity rifle. My reprint of the 1924 Rigby catalog from Cornell Publications (cornellpubs.com) claims a muzzle velocity of 3,000 fps.

Rigby also chambered its No. 1 rifle in .275 that used ammunition loaded with traditional 175-grain bullets, both “solid” and “soft nose.” Apparently the only difference between the two models was the “regulation” of the rear sight, with one fixed and two folding leaves. The No. 1’s sight-leaves were set for 100, 200 and 300 yards; the No. 2’s sight was set for 100, 300 and 400 yards. The catalog illustrations for both rifles are identical, along with their other listed features: “Pistol Hand Sporting Stock” with a 23.5-inch barrel and a weight of about 7.5 pounds.

Rigby also offered a No. 3 Light Weight rifle with a 21-inch barrel in .275 “. . . for either the ordinary, or high velocity ammunition,” weighing almost a pound less, “. . . particularly suitable for a lady or youth.” All three .275 rifles were built on 1898 actions from the Mauser Werke in Oberndorf, like other Rigby bolt actions.

Rigby also claimed, “The difficulty of estimating distances does not exist unless for a shot over 300 yards.” That might be true if muzzle velocity was actually 3,000 fps, but with the smokeless powders then available, actual velocity was probably around 2,700 to 2,800 fps – except, perhaps, on a particularly hot day. Early smokeless rifle powders tended to be rather temperature sensitive, especially the long-stranded British powder called cordite.

Rigby eventually added a load using a 140-grain semi-pointed softnose. My oldest edition of Cartridges of the World (1972) states this occurred because Rigby’s “. . . Managing Director was struck in the head by a German 8mm spitzer bullet in the course of [World War I]. Since the projectile bounced off his skull, he concluded the pointed type bullet was not satisfactory against bone!”

One famous .275 Rigby fan definitely disliked the “hollow tube” 140-grain ammunition, which he called “the copper-pointed” load. This disgruntled hunter was not W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell of Africa or James Corbett of India, perhaps the two most famous .275 users. Bell used heavier, roundnose solids on elephants – and apparently every other kind of big game as well, claiming the bore of his .275 had never been “polluted” by an expanding bullet.

Tigers can weigh over 500 pounds, which would seem to recommend the 175-grain load, but Corbett apparently preferred the 140-grain version of the .275 due to flatter trajectory, even though on one occasion a “soft-nose, nickel-encased, split” bullet failed to penetrate the shoulder of another man-eating tigress that ran off wounded. After several days of tracking, Corbett finally finished the job, finding the initial bullet in the shoulder joint.

Oddly, the other famous fan of the .275’s 140-grain load is today widely known as a big-bore boy. John Taylor, an Irish ivory poacher in the era following Bell, had this to say in his popular 1948 book African Rifles and Cartridges, which is still in print more than 70 years later:

Taylor’s book lists the muzzle velocity of the 140-grain load as 2,750 fps. The 1972 Cartridges of the World lists 2,800 fps in the write-up of the round in the chapter “British Sporting Rifle Cartridges,” though the ballistic table at the end of the chapter shows 2,900 fps for a bullet designated “140CP,” probably meaning copper-pointed.

Taylor’s opinion of the copper-pointed bullet sounds similar to criticisms of early plastic-tipped bullets, before bullet companies realized how much the tip “enhanced” expansion. Many hunters attributed the over-expansion to the separate tip driving down into the bullet, the common theory about the Bronze Point, but slow-motion videos of bullets shot into clear ballistic gelatin show the tips actually drift ahead of the expanding bullet. The violent expansion is probably due to the large hollowpoint necessary to accommodate the tip’s shank.

The 7x57 has a long, romantic history, and among some hunters the .275 Rigby’s aura is even greater, partly due to the reputation of the Rigby firm. Historically minded hunters do not always desire the latest high-tech rifle advancements, one reason for the thriving retro-market for new but traditionally styled rifles.

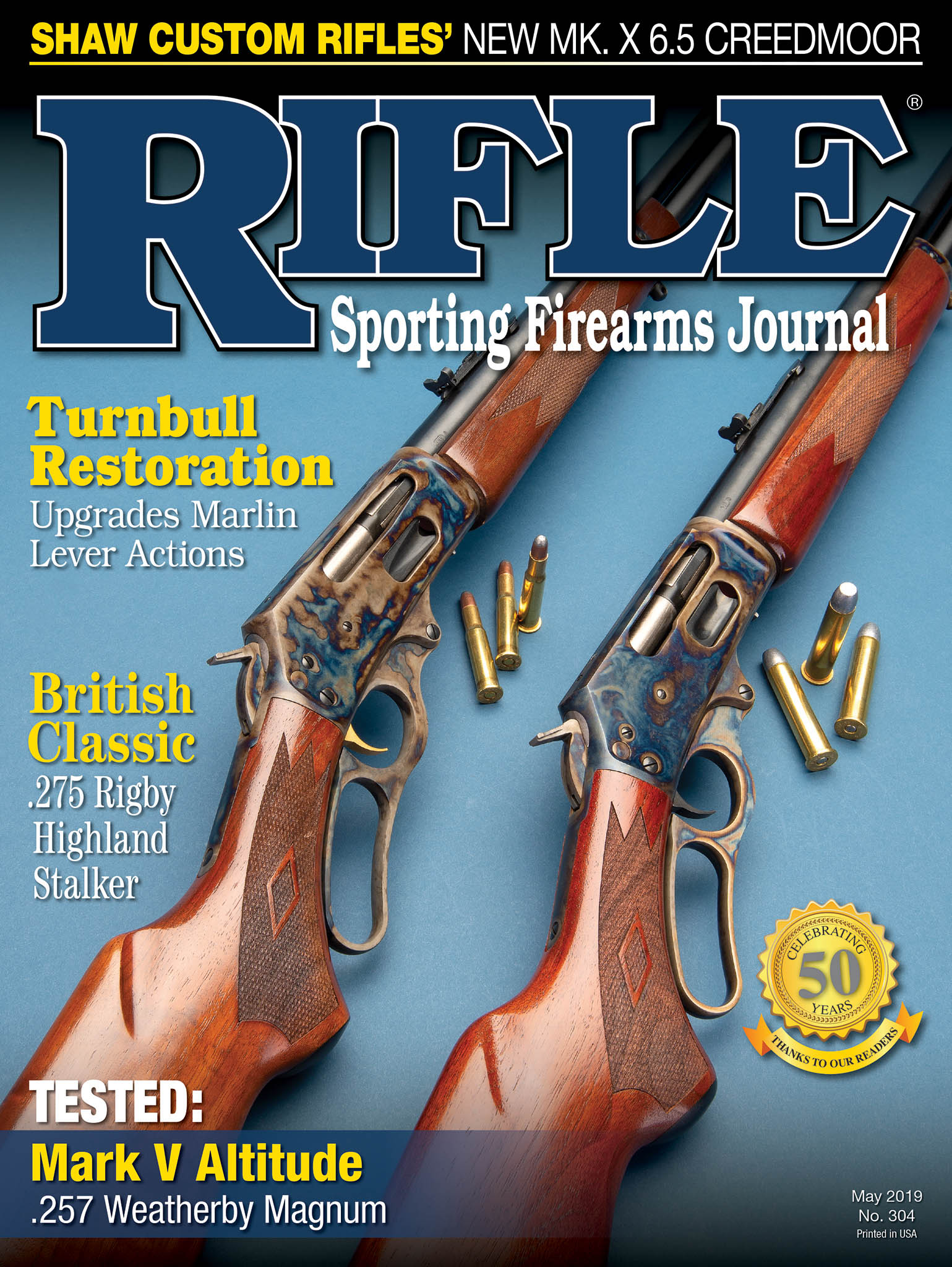

In 2017, Rigby introduced its Highland Stalker rifle, a somewhat modernized version of the No. 2 rifle, and among the five available chamberings is, of course, .275 Rigby. The others are the .308 Winchester, .30-06 and the 8x57 and 9.3x62 Mausers.

At about the same time, at least one other firearms company produced two rifles stamped .275 Rigby, and Hornady introduced .275 Rigby ammunition in its Custom line with 140-grain InterLock Spire Points at a listed 2,680 fps, along with component brass. This created a flurry of .275 interest, and I was able to persuade Rigby to briefly send a Highland Stalker for testing.

However, if shooters might desire a little shorter LOP straight from the factory, there’s also a “ladies” model with a 137⁄8 LOP and “a rounded recoil pad with ladies’ toe.” This twenty-first-century version, however, is not listed as lighter than the standard, probably because barrel length is 22 inches for both standard and ladies’ models, not the 23.5 or 21 inches for the originals. The weight for both models is 7.8 pounds, of course varying somewhat with wood density and chambering. The test rifle weighed 7 pounds, 13 ounces.

The action is still made by Mauser but is modified for scope mounting. The original Rigby rifle featured a bolt handle and safety that interfered with low-mounted scopes. The military safety lever operated in a half-circle over the top of the bolt sleeve, the reason the 1924 catalog shows “Rigby’s New Telescope Sight” with very high detachable mounts.

The Highland Stalker’s more elegant bolt handle is much lower, and the safety is another version of what is commonly known as the three-position Winchester Model 70 safety, operating horizontally on the right-hand side of the bolt sleeve. With the lever all the way to the rear, the firing pin and bolt handle are locked in place. Pushed to the middle position, the firing pin is still locked on “safe,” but the bolt can be opened. Pushed all the way forward, the rifle is ready to fire. The top of the action is drilled and tapped for modern scope-mounting bases.

The three-leaf rear sight closely resembles the original model. Compared to the illustration in the 1924 catalog, it appears to be mounted slightly farther to the rear, and instead of the leaves being set for 100, 300 and 400 yards, it is regulated for 65, 150 and 250 yards, probably because anybody wanting to shoot beyond 250 will mount a scope. (Hunters from a century ago were far more optimistic about the long-range potential of multi-leaf open sights.)

I did not mount a scope for several reasons, the least important being wary of inadvertently scratching a rifle retailing for almost $10,000. More importantly, the Highland Stalker’s weight meant even a lightweight scope and mounts would add close to another pound. One of the long-time virtues of the 7x57/.275 is plenty of “killing power” combined with light recoil in a light rifle – something all three famous .275 fans mention in their books.

Another reason cropped up when I found a test target in the rifle case, fired at 65 yards with the standing leaf and Hornady 140-grain ammunition, the three shots forming a horizontal, overlapping line .38 inch from center to center. The target was fired by somebody named Jamie Holland, with a signature next to the printed name. It would be logical to assume the shooting took place on an indoor test range, but even so, the group stands as a great testament to shooting skill and, perhaps, young eyes.

My eyes aren’t so young anymore, but I still shoot a lot with iron sights so am usually able to group three shots with a rifle’s preferred ammunition into less than 2 inches at 100 yards, even with much cruder sights than the Rigby’s. Unfortunately, no Hornady .275 Rigby ammunition could be located, whether in local stores that had sold a few .275 rifles, on the Internet or even from Hornady. This indicated the .275’s reintroduction was a success, but the shortage is no doubt partially due to a limited run of ammunition; Hornady lists it on its website, indicating more will be made sometime.

However, I did locate several boxes of Hornady .275 brass at a local store. I bought some and somewhat reproduced the factory ammunition using 139-grain Hornady Spire Points and Hodgdon H-4350 powder. Long experience with several 7x57s had proven H-4350 very accurate, and 47.0 grains duplicated Hornady’s 2,680 fps, which consistently grouped three shots into about 1.5 inches at 100 yards.

During testing of the sight regulation, I was assisted by friend Jay Rightnour, partly because I do most of my shorter-range testing on his personal range and he happened to be there that afternoon. Jay also shoots pretty well with iron sights due to competing in black-powder cartridge silhouette shooting.

Jay and I tried the sights on the abundant rocks scattered across the hillside above his range, using a laser rangefinder to determine distance. We had done this before with several other rifles, including my .416 Rigby, which Jay declared to be the best “rock rifle” he’d ever fired because it easily turned even big rocks into smaller targets, some very suitable for the .275. We both whacked rocks (or severely scared them) out to 250 yards thanks in part to the crisp trigger, which according to my Timney trigger scale broke right at Rigby’s advertised 2.5 pounds.

I strongly suspect Bell, Corbett and Taylor would really like the twenty-first-century version of their .275s. I also suspect Corbett and Taylor would like the Hornady ammunition, since the InterLock Spire Point is a very reliable big-game bullet, especially at the moderate muzzle velocity of the .275 Rigby. I’ve used the 139-grain version from the 7x57 on game from Coues’ deer to caribou, and an extra grain of bullet weight will work at least as well!