Accurizing Bolt-Action Rifles

Factors and Considerations

feature By: John Barsness | March, 19

From what can be gleaned from my collection of shooting literature going back to the late 1800s, home “accurizing” of rifles didn’t become popular until the 1950s due to several factors.

Before World War II, relatively few shooters (especially big-game hunters) used telescopic sights, so they rarely worried when their favorite rifle refused to group inside an inch at 100 yards. Prewar accurizing was mostly limited to fitting “peep” sights, because most scopes cost a lot, especially during the Depression when few Americans could afford such luxuries. While Bill Weaver started making fairly affordable scopes in 1930, the war prevented the civilian scope market from taking off – though it started growing soon afterward.

Many returning soldiers had never fired a rifle before the war but discovered they liked to shoot, so they bought rifles and even began hunting. However, for a while U.S. factories were being reconverted from wartime production, so many of the new shooters started “sporterizing” inexpensive and abundant war-surplus rifles.

One advance making this possible was epoxy. While epoxy compounds had been around since the 1890s, the basic kinds we know today were developed in the 1930s and first commercially produced in 1946. Gunsmiths started using epoxy to bed barreled actions in rifle stocks, applying a release agent (often shoeshine or car wax) to barreled actions so the metal could be removed from the wood after the epoxy cured. This bypassed the drudgery involved in hand-inletting wood stocks, with more precise and durable results.

This coincided with the growth of a new target sport called benchrest shooting that was primarily promoted by woodchuck shooters in the Northeast. Traditional gunsmiths often refused to “glass-bed” stocks, the common term back then, due to adding tiny glass fibers to epoxy to stiffen the cured glue. Benchrest gunsmiths were more open minded, and so were amateur gunsmiths who sporterized military rifles.

As factories started producing more sporting rifles, many shooters tried epoxy-bedding on them, often with gratifying results. At the time, close hand-inletting was considered one sign of rifle quality and was regarded as essential to accuracy. Some rifles even featured an extra barrel screw in the forend to

further stiffen the connection, like the pre-’64 Model 70 Winchester. Consequently, most epoxy artists fully bedded the barrel channel; some even claimed fiberglass epoxy inside the barrel channel prevented the forend from warping, a common problem with wood stocks.

Meanwhile, other manufacturers started making products with epoxy, including boat hulls, produced in molds using layers of fiberglass cloth. Eventually adventurous gunsmiths used the same technique to make stocks.

Unfortunately, thin-shelled fiberglass stocks tended to compress or collapse when action screws were tightened. Somebody soon borrowed an idea from Mauser military rifles with steel cylinders surrounding the action screws, so the screws would remain tight even as wood stocks dried and shrank. Epoxying steel or aluminum “pillars” into the action screw holes of fiberglass stocks – and eventually wood – prevented their collapse.

In 1964 Winchester introduced a new version of the Model 70 with an oversized forend channel to allow barrels to vibrate freely during firing. Traditionalists considered this a subversion of traditional values, but some shooters actually tried the new Model 70s, discovering they usually shot as least as accurately as the old model and tended to retain zero more consistently.

Today free-floating is perhaps the most common accurizing technique, partly because some manufacturers still produce rifles with closely inletted barrel channels, often with a slightly raised hump inside the forend tip (often called a “speed bump”). One major factory even claims the speed bump improves accuracy more than free-floating due to dampening barrel vibrations, though that has not been my experience after floating barrels on several of the company’s rifles.

Here it should be mentioned that a well-known test for free- floating barrels is inadequate. The test involves folding a dollar bill in half and sliding it between the barrel and forend: If the bill slides along easily, then the barrel is free-floated. Unfortunately, rifle barrels flex during firing, so this static test proves nothing since the barrel can still tap the forend, resulting in “fliers.”

For years my test has been to grab both the barrel and forend tip in my right hand and squeeze. If the barrel contacts the channel, it needs to be floated more. Reader Ralph Jones uses another simple test that may be even more effective – slapping the forend near the tip with “moderate force.” If the stock hits the barrel, it can during a shot as well. All of this is why a round rasp is one of my basic accurizing tools, used not just to remove “speed bumps” but, if necessary, to deepen the front end of the forend channel where forend contact normally takes place.

Free-floating improves accuracy in most rifles, though some light-contour barrels shoot better with forend contact. In my experiments, only rarely has installing an epoxy speed bump helped accuracy; instead full-length “neutral” bedding has worked more consistently. The big trick in full-length bedding is to make sure of even contact all the way to the very tip of the forend.

Epoxy-bedding the action and free-floating the barrel worked with war-surplus bolt rifles, but it also usually required bedding an inch or two of the barrel in front of the action due to the location of the front action screw. Most surplus rifles had the screw hole in the middle of the recoil lug, and if the rear of the barrel was not bedded, tightening the front action screw could bend the front of the action downward.

In a typical two-lug bolt action, the lugs are oriented vertically with the bolt closed, so even slight bending could result in uneven lug contact and accuracy problems. This was particularly true of abundant military Mauser actions due to the “thumb cut” in the left side of the receiver for inserting cartridge clips into the top of the action. But it could also occur with stiffer actions. Japanese Arisakas, 1903 Springfields and 1917 Enfields also had the front action screw in the recoil lug like most centerfire bolt actions throughout the first half of the twentieth century, including sporters such as the Model 54 Winchester and early Sakos.

As a result, bedding the rear of the barrel became standard procedure during the great postwar sporterizing era, thanks in part to quite a few magazine articles describing epoxy bedding. However, most articles did not explain why the rear of the barrel needed bedding, so many people assumed the barrel somehow needed “support” – perhaps due to attitudes from the tight-inletting era.

Eventually many rifle companies started placing the front action screw behind the recoil lug, which prevented bending of the action. The Model 70 Winchester is one prime example, the reason post-’64 Model 70s shot so well with completely free-floated barrels.

In 1948 Remington also placed the front action screw behind the recoil lug in its new Model 721 and 722 rifles, the actions that eventually morphed into the long- and short-action 700s. In fact, postwar bolt actions with the action screw in the recoil lug are rare, and usually the receiver is stout enough to resist bending, as in the Howa and Weatherby Mark V. However, the notion of bedding the rear end of barrels for “support” lives on, even though benchrest gunsmiths gave up the practice long ago when they quit trying to make ’98 Mausers into ¼-inch rifles.

Even some professional gunsmiths miss the fact that the entire point of epoxy bedding is to relieve stress on the action. Instead, after carefully applying release agent to the metal then slathering mixed epoxy into the stock inletting, they tighten the action screws as hard as they can. This may work but will probably bend the action slightly, the reason some people simply wrap the action in the stock with surgical tubing.

I have done the job both ways, but if a shooter decides to use the action screws, they need to be heavily coated in release agent and tightened only until they barely start to snug up. At that point, I back them off very slightly, which may or may not help, but doing so definitely doesn’t hurt.

Another accurizing development occurred due to the Remington 700/721/722 recoil lug. Instead of being integral to the action as it is on the ’98 Mauser and Model 70 Winchester, it is a separate part installed when the barrel is screwed into the action. Quite a few gunsmiths felt the lug was too small and thin to resist recoil forces in harder-kicking rifles, so they started making thicker, longer lugs. Nowadays, many “home accurizers” install these lugs when working over Remington 700s.

However, oversize recoil lugs may actually be counterproductive, according to research detailed in the late Harold Vaughan’s remarkable 1998 book, Rifle Accuracy Facts. Vaughan was a prominent rocket and artillery scientist who also happened to be a rifle loony and bench shooter, and his research contradicts many long-time assumptions. (Original printed copies of Rifle Accuracy Facts, like the one I purchased new for about $30, now sell for about $150 or more. Luckily, scanned computer versions are readily available for free.)

Vaughan conducted his experiments on bolt-action rifles using technology often unavailable to even advanced gunsmiths, and he discovered considerable barrel vibration during firing was caused by the recoil lug momentarily bending the front of the action. This is partly why some twenty-first-century factory rifles feature smaller recoil lugs, or no traditional lug at all. Instead, manufacturers are using “bedding blocks” in the stock that fit into notches in the action. Some people still “skim-bed” the block surfaces with a very thin layer of epoxy, but there’s no need to bed the entire action area.

It can also help to slightly lap bolt-action locking lugs if their rear surfaces don’t show at least some wear on their engagement surfaces inside the action. Some people believe 100 percent contact is necessary, but I have experienced very fine accuracy from rifles that only showed about 30 percent contact – and with enough shooting the same lugs will eventually contact 100 percent.

Unfortunately, in a few factory rifles with two-lug bolts, one lug doesn’t make any contact at all. I’ve encountered a number of these rifles over the decades, including two in a row from one major manufacturer that replaced the first rifle because it refused to shoot groups smaller than 2 to 3 inches.

While such misfit rifles occasionally shoot pretty well anyway, many do not, and if the lug making contact is lapped enough for the other to seat, headspace normally increases enough to cause excessive case stretching, or even separation. At that point the only real cure is setting the barrel back a little, the reason lug contact is among the first things I check with any new-to-me rifle.

Lugs are usually lapped by applying a little bit of abrasive compound to their contact surfaces, then working the bolt handle up and down while applying rearward pressure. There are two schools of thought on this. One is that since pressure from the trigger mechanism tends to tilt the rear of the bolt upward slightly (unless, of course, the bolt fits very tightly in the action, which is rare in factory rifles), the firing pin and spring should be removed during lapping so the lug surfaces are lapped squarely to the bore.

This, of course, assumes the bolt face needs to be perfectly square to the bore. Otherwise firing will supposedly deform the case head slightly, causing accuracy problems. However, most rifles go bang when the bolt is tilted upward slightly.

Vaughan tested all of this, and accuracy was better when the lugs seated fully with the bolt tilted upward – indicating lapping should be most effective when performed with the firing pin and spring in place. In fact, one of his test rifles was a Remington 721 he had owned for a long time, with locking lugs that “self-lapped” over the years. He replaced the worn bolt, whereupon the rifle shot less accurately. (Vaughan also could not find any correlation between accuracy and slight variations in bolt-face angle, apparently because cartridge brass is pretty flexible.)

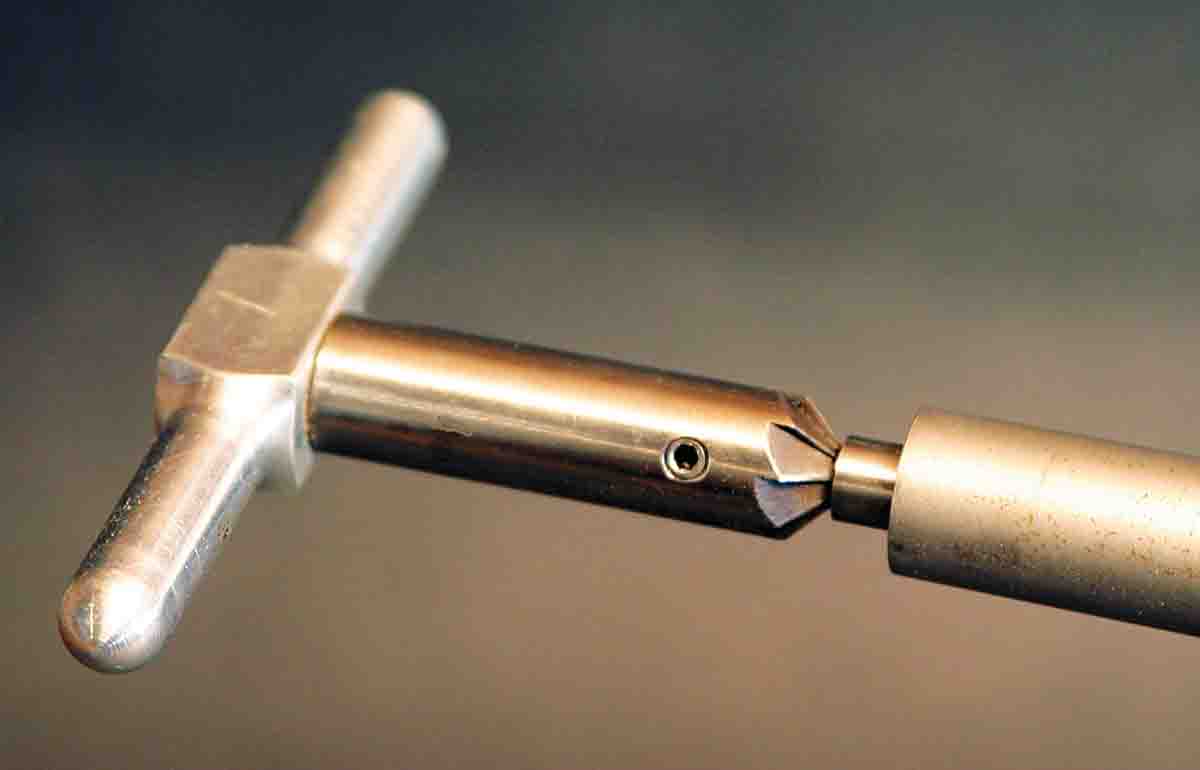

Recutting the muzzle crown, however, can really improve accuracy, especially the traditional, rounded crown. These days, more and more factory rifles feature versions of “target” crowns with a much sharper angle between the crown and bore, but these can also be dinged more easily than rounded crowns. Some of my own rifles have shot measurably better after recutting the crown with a Brownells hand tool purchased in the 1990s.

Of course, if a shooter doesn’t want to tackle all this, quite a few gunsmiths and custom rifle companies will perform the job. In 2017, Hill Country Rifles (hillcountryrifles.com) offered to perform its basic accurizing job on one of my rifles. After considerable thought, I selected a recent Model 70 Winchester .300 WSM put together in Portugal and purchased new at Capital Sports & Western Wear in Helena, Montana.

Immediately after bringing the rifle home, the bolt was removed to see if both lugs made contact. They did. So after squeeze-testing the free-floated barrel (it was fine) I removed the stock and checked out the epoxy bedding of the recoil lug area, which looked good.

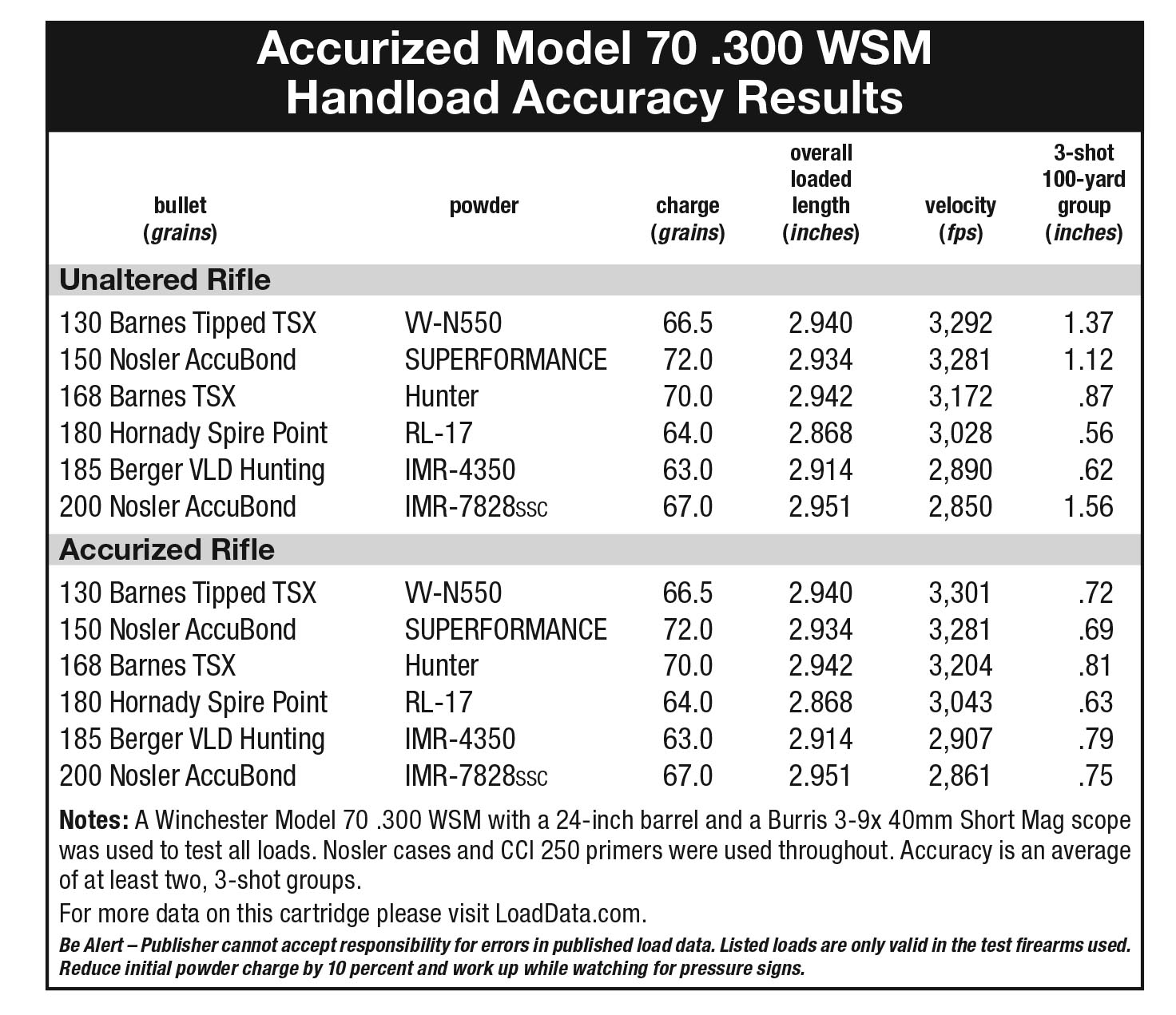

Overall, the Model 70 shot pretty well for a factory rifle, with several handloads grouping three shots consistently into .5 to .8 inch at 100 yards. However, a few averaged 1.5 to 2.0 inches, including the “best” load with a bullet I really wanted to use for hunting, the Nosler 200-grain AccuBond. While some hunters prefer lighter bullets at warp speed in .300 magnums, I tend to prefer bullets around 200 grains, since they both penetrate deeper and drift less in wind.

Hill Country’s basic package includes recrowning, fully epoxy/pillar bedding the action, lapping scope rings for precise alignment, inspecting locking-lug contact and chamber, testing headspace and trigger pull, then correcting anything if necessary. After all that, the rifle was bench-tested with Federal Premium 180-grain Power-Shok and Fusion ammunition that provided three-shot groups measuring .504 and .610 inch.

I later retested the rifle with six handloads shot prior to sending it off. Half shot well under an inch and half shot over an inch. As expected, there wasn’t any definitive difference in the more accurate loads, but I didn’t really expect any, because obviously the rifle had “good vibrations” with them already. However, now all the groups were under an inch and the Nosler 200-grain AccuBond load went into .75 inch!

It doesn’t really take a vast amount of accurizing to remove the typical flaws in a factory rifle, such as a “free-floated” barrel that is not really floated. However, more refined accurizing can cut groups in half with loads the rifle did not like.