Spotting Scope

Old Guns and Old Sights

column By: Dave Scovill | March, 19

Our editor recently asked if I might consider a column about open and/or aperture iron rifle sights. Apparently the subject comes up on a reasonably regular basis, enough so to consider a refresher course on the proper use of open sights.

This may sound a bit brisk, but those who were unfortunate enough to start out using scopes on a .22 rimfire or centerfire hunting rifle and came to rely on them, are likely lacking in skill required to successfully shoot a pre-1900 Sharps, Winchester lever actions or single shots, Marlin leverguns or double rifles, etc. I know some of those folks are writers, mostly because they end a test with an open-sighted rifle with: “That’s about as good as I can do with open sights.” Some of those folks are senior citizens, of course, so they may have a legitimate reason for marginal eyesight: glaucoma, cataracts, near or far sightedness, etc.

For shooters with normal vision who don’t know how to use open sights, there is little chance that their children will learn to use them either. One wonders if we are becoming a nation of nonriflemen whose parents, by the fickle finger of fate, saw the movie A Christmas Story, and kids were unknowingly denied the joy of childhood with a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun.

I was reminded of the Red Ryder while walking through the local ranch store a while back and happened to wander down the aisle with the gun-related stuff, and there it was, in a big fancy box, and I immediately wondered what happened to mine, a gift on my fifth birthday, December 1949. It was wrapped in white butcher paper from the local fish market, and another package contained a box of BBs.

My father instructed me on how to load the gun, line the sights up and pull the trigger. He probably said something about not pointing the gun at my sister, or some such, but whatever cautions he offered apparently did not fall on deaf ears. I knew to not point a gun at anyone, and vividly remember Mother telling me to not bring dead mice in the house.

We moved to the Associated Plywood logging camp about 45 miles out of Roseburg, Oregon, in the late summer of 1955. Forest fires and storms kept loggers out of the woods, and Mother cautioned that Christmas might be slim. I received a pair of Converse tennis shoes for a birthday present in mid-December and figured that was about it. I salvaged enough money for a box of .22 shells and, when I wasn’t fishing, passed the time hunting silver gray squirrels with the J.C. Higgins .22. Squirrel tail hair was used on streamer-type flies, and the squirrel meat, wrapped in tinfoil with bacon grease and a little flour, was cooked on a spit over red-hot coals.

On Christmas morning the living room in company housing was a bit crowded with the five of us around the tree, and Mom commenced the honors of passing out presents. When she finished, she went to the kitchen to start breakfast, then yelled she forgot something, scrambled upstairs and returned shortly with a long cardboard box with “Winchester” in big red letters down the side. In smaller print on the end flap it read, “Model 69A.”

In the following years, the Winchester clip-fed bolt action was used to take hundreds of jackrabbits, cottontails, squirrels, grouse, one very stupid coyote and a couple of big mid-winter bobcats.

A few years later, my stepfather had a Lyman 4B scope mounted on it. I tried the scope for awhile, then removed it. I couldn’t get used to the relatively narrow field of view when compared to shooting with both eyes open with iron sights, and since it rains a lot in western Oregon, the lenses were constantly wet, regardless of efforts to protect the scope under a jacket.

At traditional .22 rimfire ranges, say out to 100 yards or so, I didn’t notice a significant difference in accuracy with iron sights compared to a 4x scope. If there was a difference, my guess is that it is largely due to ammunition, say .5 to one inch at 100 yards with one brand compared to one inch and somewhat larger with other brands. Then too, when shooting at a running high-desert jack-rabbit that hits its stride at more than 30 mph across the alkali flats, zig zagging left, then right, minute of angle isn’t the biggest concern when attempting to establish the proper lead.

Shooting at running targets is probably the best real-time practice for an open-sight shooter, experienced or not. The interesting part is that I noticed friends using scoped rifles, mostly .22s, were usually so strung out over achieving pinpoint accuracy that they rarely got a shot off before the rabbit was long gone.

Of course, anyone who has shot birds knows how to pass-shoot, but even fairly good wing shooters tend to forget the basics with open sights on a rifle, apparently because they get hung up on the fact that there is only one bullet in the rifle and worry too much about missing. In short, there is a very good reason for not mounting scopes on bird guns. Inexperienced shooters who might use open sights from a benchrest get so hung up over not having a magnified view of the target, they tend to think marginal accuracy is acceptable, blaming it on open sights. (See comment above.)

The first rule of using open (iron) sights is to avoid making it overly complicated. Millions of kids ages 5 to 10 have figured it out with the Red Ryder, so it shouldn’t be too hard for an adult. Then too, people who think they know a lot about shooting have quite often incorporated one or two bad habits into their technique, and it is difficult to shed them.

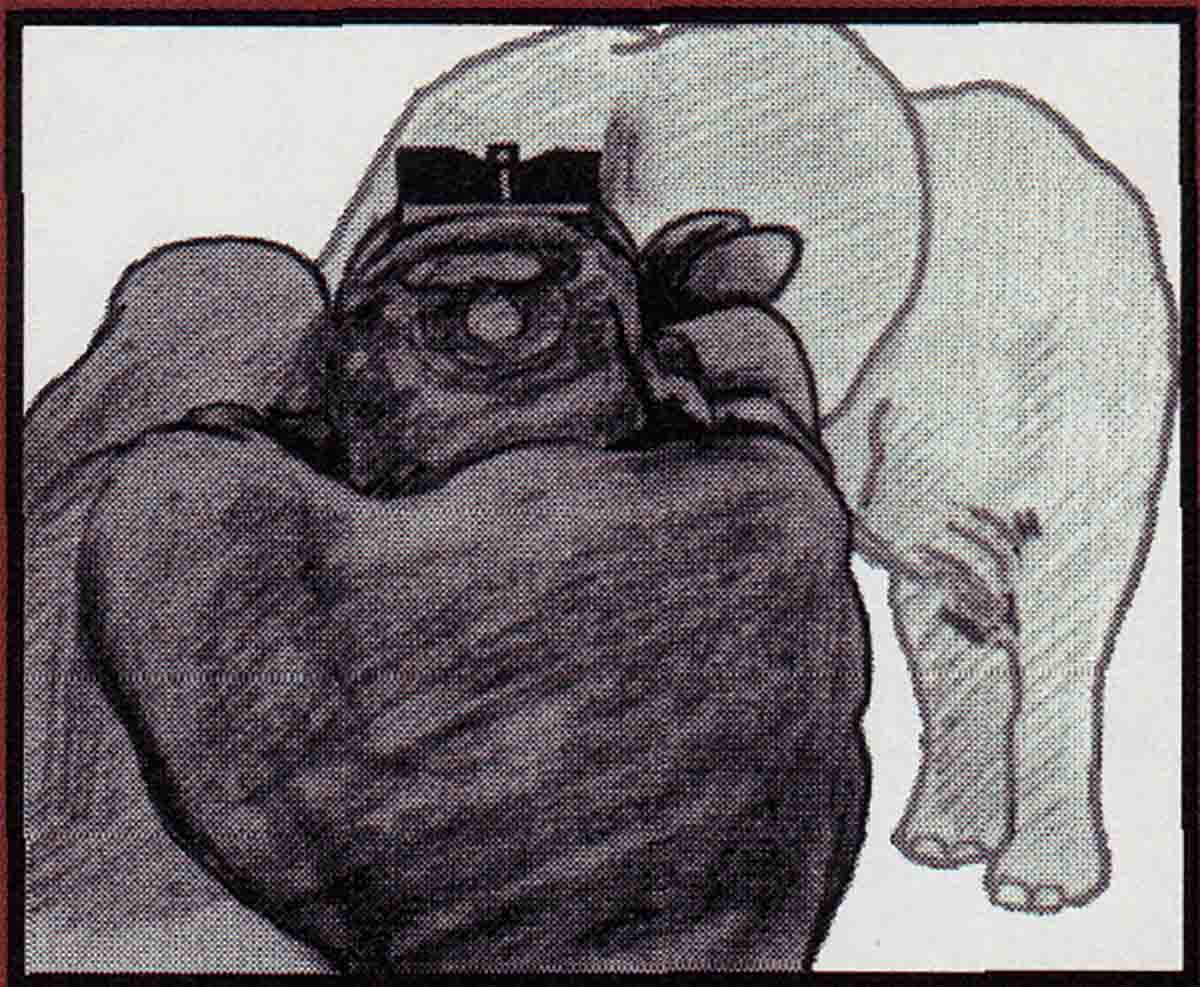

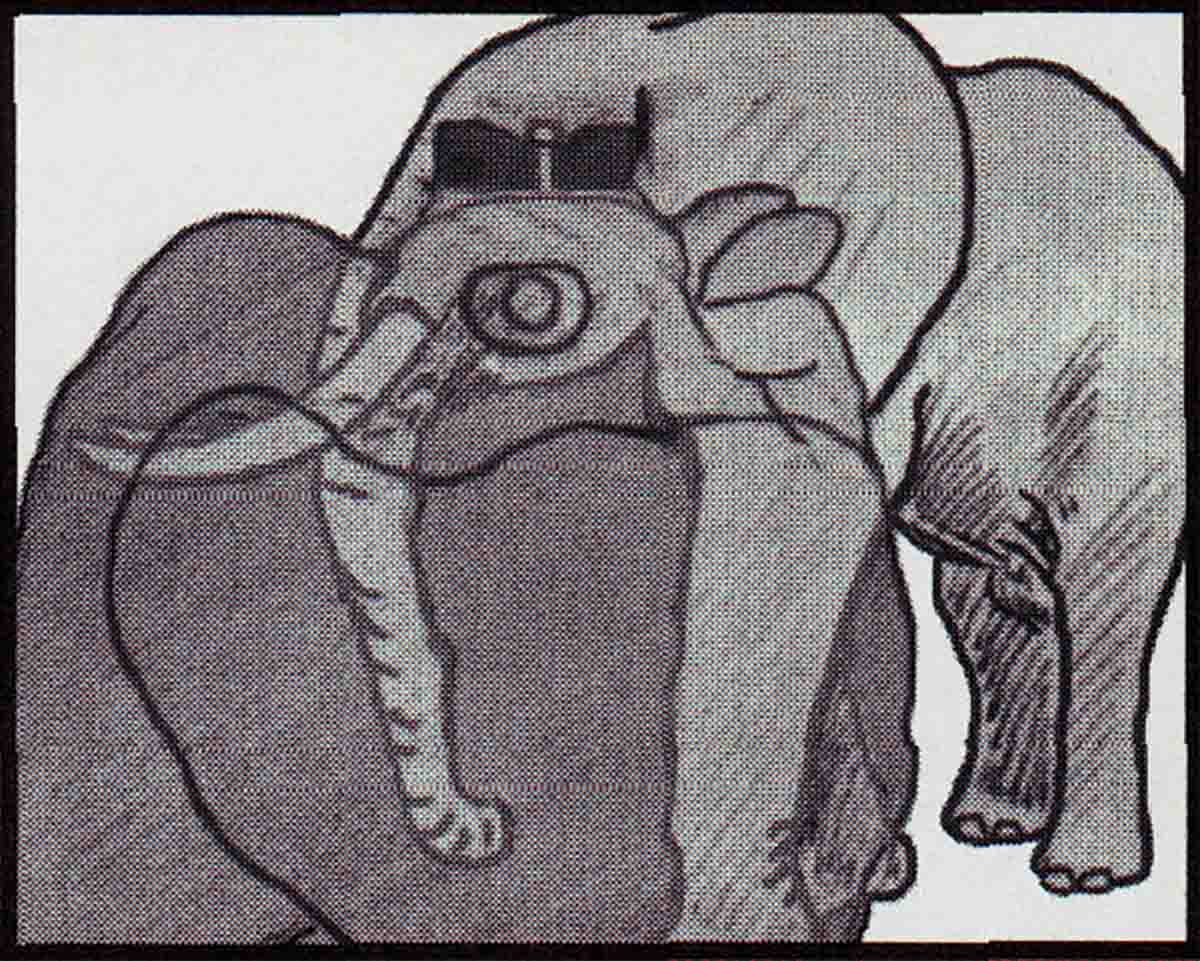

The first bad habit to get rid of is closing the off-side eye when shooting with scopes. Accurate shooting with open or aperture sights pretty much requires the use of both eyes, to avoid the front sight and part of the barrel blocking out part of the target. The use of both eyes not only allows the shooter to see the entire target, but peripheral vision also sees the area surrounding the intended point of bullet impact, and two eyes are necessary to properly judge distance.

The nearby drawings from Bell’s Wanderings of an Elephant Hunter illustrate how the target, a bull elephant in this instance, should appear with both eyes open and/or one eye closed with a double rifle.

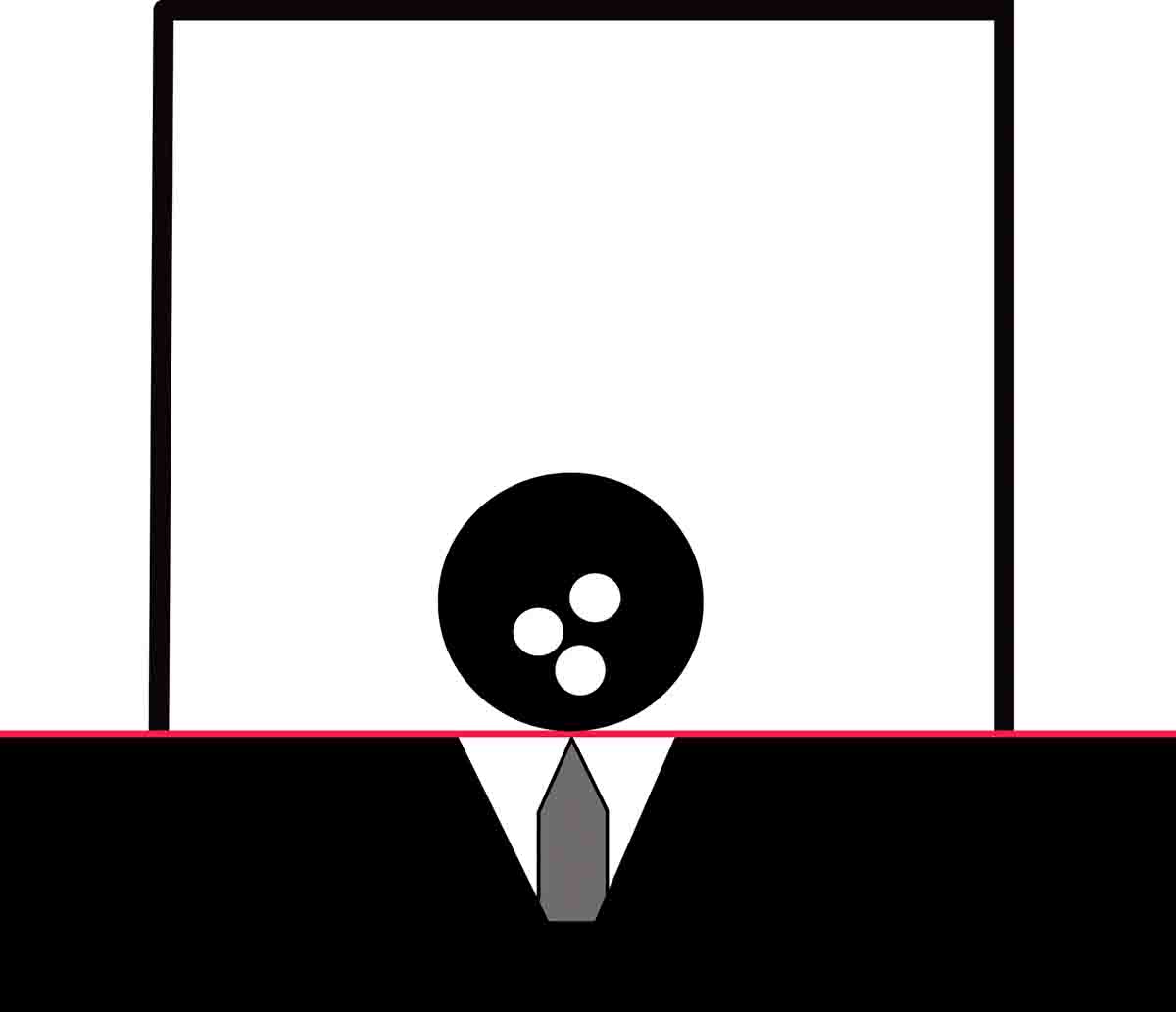

The illustration of the Winchester rifle’s sights against the backdrop of a target represents approximate bullet impact of about 3 inches high at 100 yards. With the rear sight properly elevated in the notches on the riser, from 50 to 300 yards in 50-yard increments, the relationship between the top of the front sight and the target should be the same, albeit the target appears smaller as distance increases.

After using that Winchester sight drawing as my original reference nearly 60 years ago, the relationship between the top of the front sight, the upper corners of the rear notch and the bottom (6 o’clock) of the target are all located on a single horizontal line.

Winchester suggested the top of the front sight should be about 1⁄32 inch above the bottom of the rear notch, which should place the bullet 3 inches high at 100 yards. Because my brain has never figured out exactly what 1⁄32 inch is, I learned to compensate by holding the sight picture a bit tighter against the bottom of the target. In the field, where the heart/lung area is at least 12 inches in diameter, it’s a wash, even with the rear sight set in the fourth notch up (200 yards), fifth notch (250 yards) and sixth (300 yards) on an 8- to 12-inch black bull’s-eye. Of course, the Winchester drawing assumes the use of factory loads.

My longest shot in the field with open sights on big game has been approximately 220 yards with a Model 1886 Winchester .50 Black Powder Express in Zimbabwe. Winchester and Sharps rifles in various calibers and persuasions have accounted for grizzlies, brown and black bear, Cape buffalo, hippopotamus, a couple of elephant, a bunch of African plains game, mule deer, pronghorn, elk, a couple of bull bison and countless rabbits and squirrels.

The most important fact to keep in mind is to always concentrate and focus on the front sight. That may leave the rear sight a bit out of focus and the target might be a bit fuzzy, but for the most part in focus. Do not shift focus back and fourth from the target to the front and/or rear sight, as some scribes have written over the years – which is perfect proof they don’t have a clue about the proper use of open sights. The key is to concentrate on the front sight, and if you don’t already have one, go out and buy a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun and share it with the children.