You can see why the early Colt Pythons with their spectacular blue finish and Eliason Kensight sights were regarded by many as the ultimate 357 Magnum.

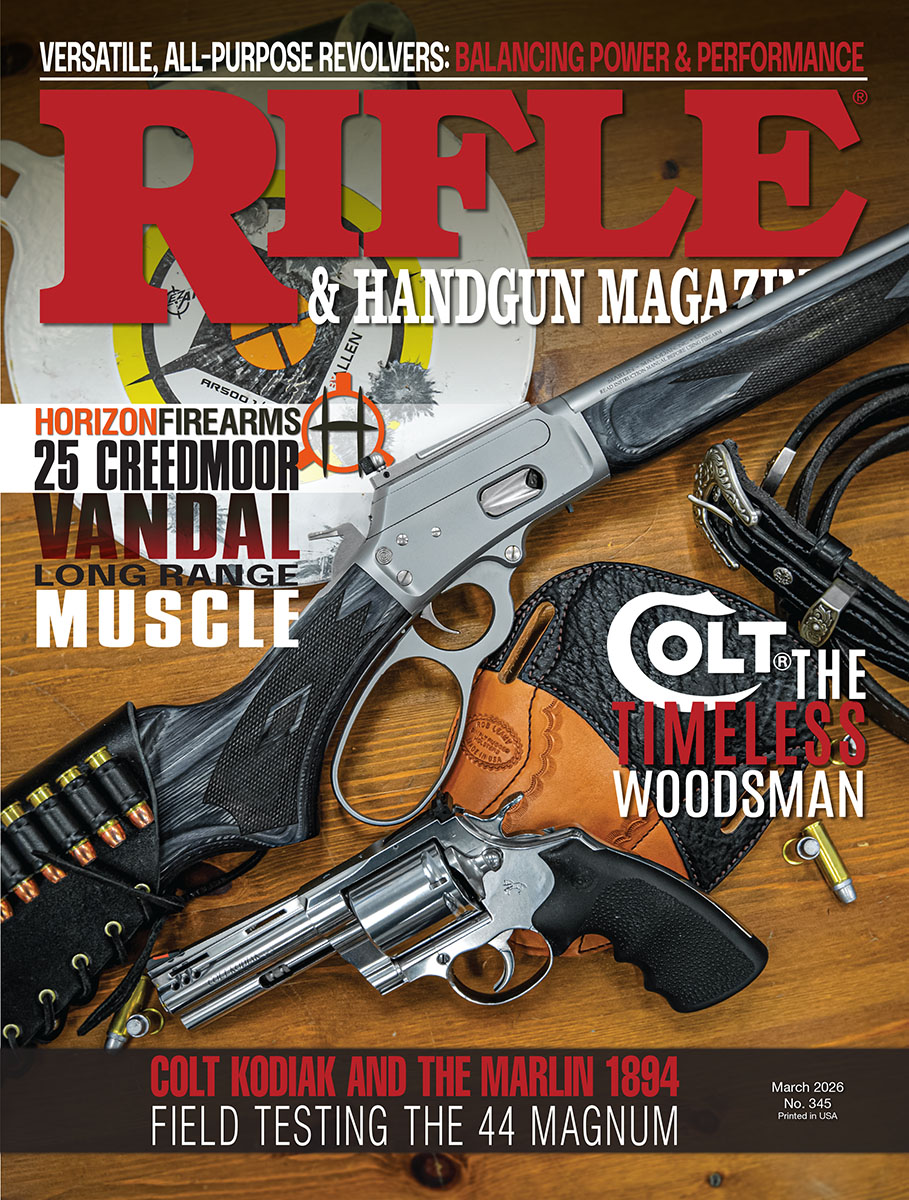

In a recent phone conversation with Jeremiah Polacek, Editor of Wolfe Publishing Company, I learned that the company’s Rifle magazine is being modified to include handguns. Fantastic news! I’ve enjoyed the quality content of Rifle over the years, and my only regret was the absence of handgun articles. Since both Jeremiah and I are serious revolver fans, we were extremely interested in coming up with an article suitable for the magazine’s new look. In the course of our dialogue, the descriptive phrase “all-purpose” came up more than once. Recognizing that much of America’s population firmly believes that only semiautomatic pistols are suitable for any tactical application, such as personal self-defense or law enforcement, I did not want to appear biased, or worse yet, overbearing in presenting opinions on the suitability of a well-built double action revolver for multiple purposes including defensive use.

An early S&W Model 27 with a barrel over 8 inches. When I first saw it, the gun said to me, “I’m not designed for concealed carry; I was born to hunt!”

On the other hand, when we got home with my first Model 27, and I pulled out my old Bianchi shoulder holster, it was clear my new “Buntline” could and would be carried under a coat or rain jacket when we went hunting.

To me, the magic year for revolvers was 1935 when

Smith & Wesson brought out the first 357 Magnum revolver, later named the Model 27. Prior to that, good guys and bad guys alike carried older double-action revolvers chambered for the 38 Special cartridge. Sights were minimal, trigger pulls were miserable and terminal ballistics was a subject for future generations to study. Looking at the old cops-and-robbers car chase movies with guys riding outside the vehicles on the running boards, shooting at each other, I tend to believe the only rounds that actually struck flesh did so on people in their own car. S&W changed the capabilities of handguns with the 357 Magnum, and OSHA changed car chase shootout rules by mandating the seat belt.

I wasn’t around in 1935, but I was reading about guns in the fifties, and a couple of things still puzzle me about the early days. While the Model 27 was later offered in several different barrel lengths, the first ones came with barrels over 8 inches long, which suggests a hunting weapon rather than a duty gun. In addition, the early gun magazine stories addressed the capability of the new gun and cartridge on big game hunts such as elk. I don’t recall big-game handgun hunting becoming popular until decades later, and even then, there were states that still did not allow handgun hunting of the bigger critters, even deer. However, when the 5-inch barrel model 27 became quite popular (though expensive) as a duty gun with agencies operating in more open terrain or suburban areas where longer range engagements were more common than in urban environments, the shorter barrel was prized by law enforcement officers. My favorite gun writer, “Skeeter” Skelton, carried the 5-inch model in his days as a Border Patrol agent and even chose it as his go-to gun in the event of some kind of widespread disaster.

The mid-size S&W Model 66 with its short 2.5-inch barrel is a great duty gun, whether carried in a shoulder or belt rig, but if you saw The Gauntlet with Clint Eastwood, you already knew that.

This 50-year Commemorative S&W Model 29 in 44 Magnum is a thing of beauty, but as Chief Lone Wadi said in the movie The Outlaw Jose Wales, “It’s not for shooting, it’s just for looking at!”

Following the Model 27, Smith introduced the slightly downsized Model 19 and Model 66, revolvers designated “K” frame as opposed to the larger “N” frame on the original Model 27. The Model 19 had a blue finish, while the Model 66 was made in stainless steel. With a 4-inch barrel, the guns were issued to many police departments throughout the country. These smaller guns did not handle the punishment delivered by the constant use of full-power 357 Magnum loads as well as the bigger “N” frame guns, but they were nonetheless quite popular. Their champion was another famous Border Patrol officer and gunhand, Bill Jordan. My favorite “K” frame revolver is the 2.5-inch-barreled Model 66, but I’ll admit I was emotionally influenced by the Clint Eastwood movie The Gauntlet. Besides stealing all the scenes in which the gun appeared, that 2.5-inch barrel looked like a perfect handgun for carrying concealed in either a shoulder holster or outside the waistband (OWB) belt holster.

During the latter half of the 20th century, when the 357 Magnum caliber dominated the police and civilian market, many handgunners felt the Colt Python set the gold standard for 357 revolvers. With its full-length ventilated rib, glass smooth trigger and incredibly beautiful polished blued finish, Colt’s snake was the poster child of revolvers in America. Barrel lengths were available in 2.5, 4, 6 and 8 inches, so the gun was clearly intended for more than just business use. When the trigger was pulled, cylinder lockup in the frame was tight and accuracy excellent. With extended use of magnum loads, the gun’s action did have a tendency to shake loose, and as the years went by, there were fewer and fewer gunsmiths willing to work on Pythons. Ultimately, that may have diminished interest in the gun amongst shooters, but not collectors. Prices for older Pythons skyrocketed in the first part of the new millennium. Colt reacted wisely and began production of a new generation of Pythons, built stronger and lasting longer in order to perform whatever tasks shooters asked of it.

You can’t question the qualifications of the 45 Colt cartridge given it’s 150 years of successful performance. Chambered in a S&W Model 25 with proper ammunition, it is the very definition of an all-purpose revolver.

While this stainless-steel Model 629 is also beautiful, it was born to hunt. Carried in a chest holster from Galco Holsters, the combination of gun and holster will elicit envy and hatred from all your hunting buddies.

To many of today’s Americans, whether serious shooters or serious noir movie buffs, Smith & Wesson is the definition of the pocket revolver, or “snubbie.” It’s no mystery as to why; S&W’s smallest revolvers (“J” size frame weighing less than a pound with barrel length just under 2 inches and firing a lighter weight bullet but with the same diameter as a 357 magnum) are amazing. Slip one of these in a front trouser pocket or lightweight jacket pocket, and no one will know that you’re armed. With one of these concealed on your person, you’re no longer easy prey, and with training and practice, you can become a formidable force in defense of your family. I emphasize training with snubbies because the small guns are more difficult to shoot than duty-size guns. As Clint Eastwood said in one of the Dirty Harry movies, “A man’s got to know his limitations.”

The next “magic” year for handgunners was 1956, when Smith & Wesson (S&W) introduced the now world famous 44 Magnum Model 29. I was a young teenager and couldn’t get enough reading material about the larger (“N” frame) beautiful king of handguns. There was no question about the new handgun’s intended mission; this baby was built for big game hunting, which was beginning to gain some attention and recognition as a legitimate sport. Somewhere in my files, also known as my garage, there’s a “Guns & Ammo” article by Bob Peterson of Peterson Publications about an Alaskan brown bear hunt with a Model 29. Along with Skeeter Skelton’s article titled “For the One Gun Man,” it was the other most influential article on a young, future gunwriter.

This new generation Python custom-built by Bobby Tyler will do anything you want in a duty-type handgun and still make your friends jealous when you wear it to BBQ.

As I recall, sales for the new hand cannon weren’t great once people got a taste of the 44 Magnum’s sheer power. For many buyers, the Model 29 was a “coffee table” gun used for impressing friends when they visited your house. Once folks actually fired a full-power 44 Magnum revolver, the much kinder, gentler 44 Special ammunition was used by most shooters. That changed dramatically in 1971 with Clint Eastwood’s first Dirty Harry movie, in which he explained to a number of “Lucky Punks” that, “The 44 Magnum is the most powerful handgun in the world and will blow your head clean off!” Not exactly a positive marketing pitch, but it worked. It was some time before you could buy a Model 29 since gun stores couldn’t keep one in stock. If you could find a private party willing to sell, you paid a heavy premium. Smith & Wesson responded appropriately at the factory.

Another serendipitous event in the 1970s that swelled the tidal wave of demand for 44 Magnums was the new handgun metallic silhouette shooting sport that involved toppling steel animal silhouettes at ranges out to 200 meters. The 44 Magnum dwarfed the effectiveness of lesser calibers, especially on the 50-pound rams at 200 meters. With its animal shaped targets, silhouette shooting segued nicely into big game handgun hunting in Colorado where I lived at the time. Summertime competitions with 44 Magnums provided great practice for the fall hunting season, as long as you reminded yourself that knocking down 150- and 200-meter steel targets did not qualify you to take deer and elk at those ranges.

The stainless 44 Special Model 624 is more than an adequate deer gun at moderate ranges. Talk about an “all-purpose revolver!”

As I age, my enthusiasm for shooting multiple rounds of full-power 44 Magnums in a single shooting session has waned. Fortunately, I discovered two things: 44 Special ammunition and 44 Special handguns. Doing defensive shooting drills for a day on

Gunsite Academy’s training ranges with 180 -and 200-grain 44 Special ammunition makes for a much more pleasant outing. My gun of choice for this is either a Smith and Wesson Model 24 or 624 with 2.25-inch barrels. Both are built on a S&W “N” frame specially built to Lou Horton’s specification years ago. The guns are lighter and slimmer, making them easier to conceal and comfortable for long-term carry in an OWB hip holster. I have carried them afield both on urban streets and on a doe hunt in Texas.

The S&W snub nose “J” frame with a skinny barrel less than 2 inches long is not fun to shoot with 357 Magnum loads. But as this training drill on a square range at Gunsite Academy clearly suggests, the little pocket pistol can indeed be your last chance at survival.

If I fail to mention the Smith & Wesson Model 25 revolver loaded with 250-grain lead bullets, I’d probably be stripped of my gun writing credentials and drummed out of the industry. Built on the same frame as the Model 29, it chambers the 45 Colt cartridge, which shoots larger diameter bullets at slower velocities and lower operating pressure. Kinder and gentler on the shooter but not so much on the target! You don’t need a science degree to analyze its terminal ballistics; it makes bigger holes in the target. The cartridge has been proven effective in use for over 150 years.

We’ve come to the part where I either shut up or put up! Have I made a case that quality double-action revolvers do indeed qualify as all-purpose handguns? Admittedly, an 8-inch barrel is difficult to conceal, but it can be carried under a jacket in a shoulder holster, and it does give you an advantage as engagement ranges lengthen. Unless you’re Jerry Miculek, a revolver is noticeably slower on a speed load than a semiautomatic. It does, however, allow single-round reloads, “topping off” individual rounds as you shoot and keeping your gun full. The semi-automatic’s advantage in reloading speed only applies until you run out of pre-loaded magazines. It takes me at least three hands to reload one of today’s double-width high-capacity magazines, and even then, I’m semi-helpless unless I’m carrying the special reloading tool that everyone keeps handy in their range bag.

Revolvers do not require their ammunition to “multi-task.” When you pull the trigger, the cartridge’s only purpose is to launch the bullet toward the target. If you don’t hear a “bang,” pull the trigger again. If you still don’t hear a bang, dump the cylinder contents and reload. Semiautomatic ammunition must be balanced to both power the bullet and cycle the action. Malfunctions may require some analysis beyond a simple “tap rack.” I know today’s semiautomatics are incredibly reliable and that most malfunctions are shooter-induced. To me, that suggests considering a revaluation for the enhanced simplicity of a revolver, particularly for a less experienced shooter.

I’ve traveled with double-action and single action revolvers as well as semiautomatic pistols, and I’ve never felt like easy prey or ill-prepared for taking game. Please keep in mind that Roy Rogers tamed the west using just the old single-action wheel guns seen on the silver screen. As Roy might have said, “Happy trails, whatever you’re packing.”