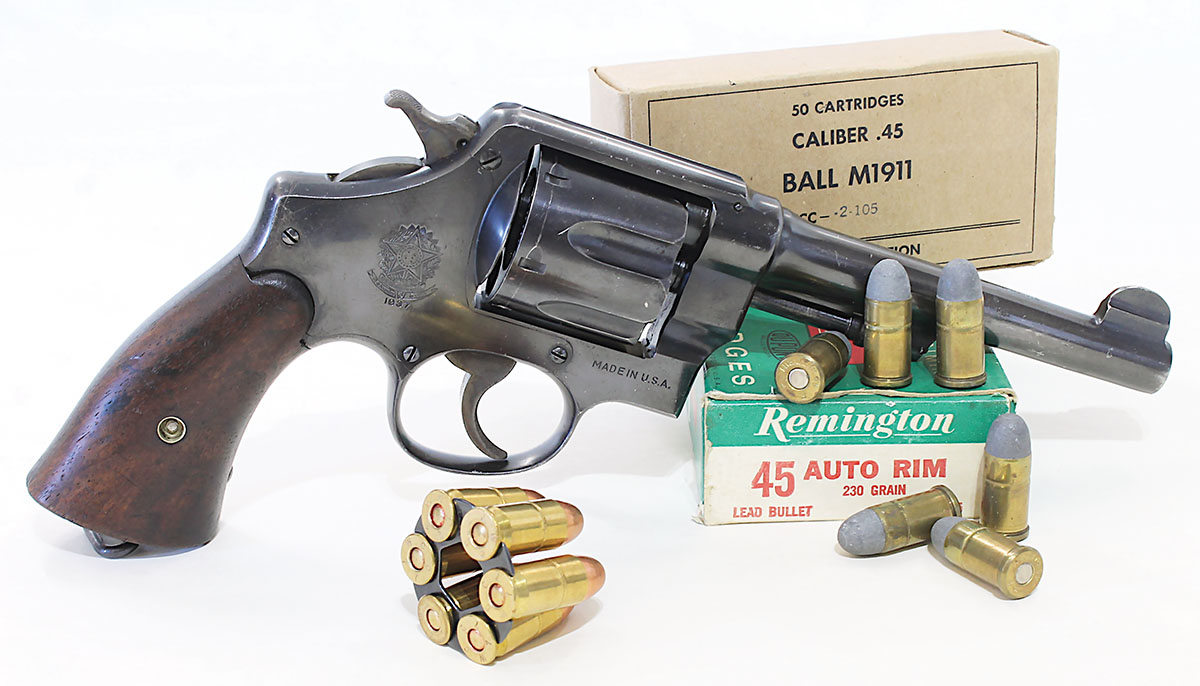

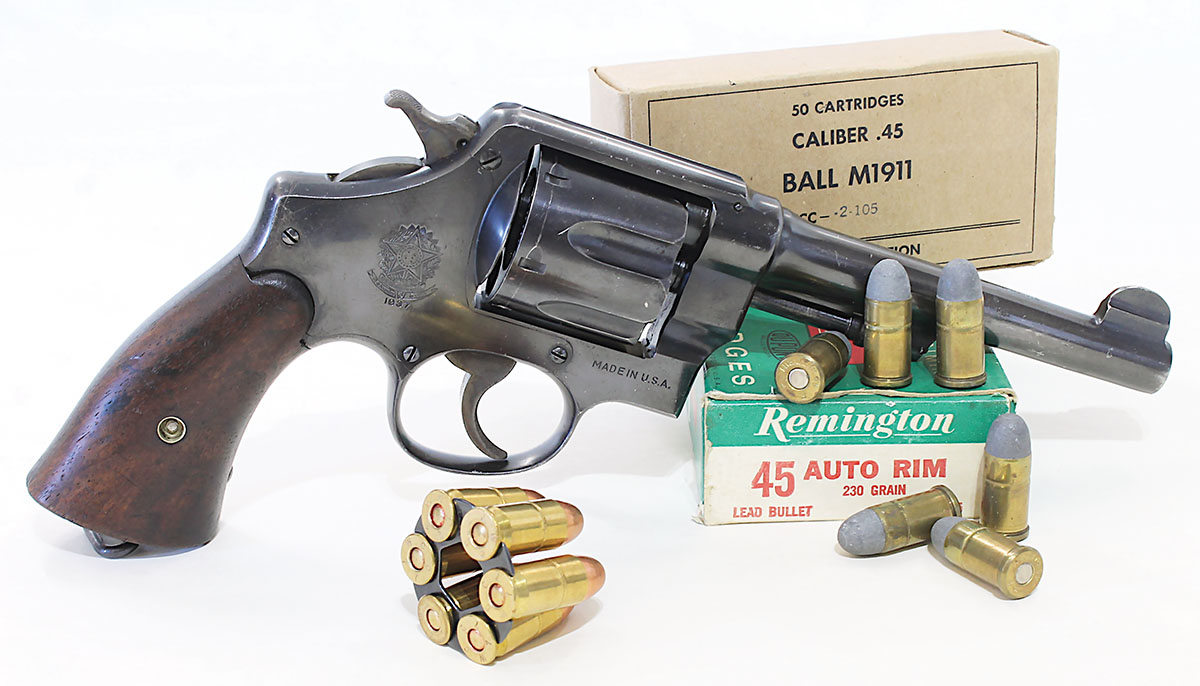

Smith & Wesson’s “Brazilian contract” Modelo 1937 has a history going back to World War I. Indeed, Smith & Wesson built many of the revolvers on World War I-era frames.

History didn’t suddenly begin at some arguable endpoint in prehistory, and history isn’t dead and gone. Rather, history is unfolding even now, moment by moment. As you sit here reading this, historical events are happening somewhere in the world, but we typically aren’t aware they are historical until we look back on them from the perspective of the future, usually because we are busy just making a living in the present.

The Modelo 1937 is essentially the 45 Hand Ejector US Army Model 1917.

That bit of nibbling at the fringes of existentialism is pertinent to the discussion here of a particular Smith & Wesson revolver with an unusual history, it having fought in war, been discarded, sent back to the front, discarded again, modified, sold to serve in a foreign land, and finally discarded once again in returning home. This is the

Smith & Wesson Model 1917 and the Brazilian contract Modelo 1937 45 ACP/45 Auto Rim revolver.

Though the 45 ACP can be fired in the Modelo 1937 without half-moon clips, the clips are needed for rapid reloading and to engage the extractor, as it cannot reach the 45 ACP rim.

To understand the Brazilian contract revolvers, we must go back in history to World War I. The Brazilian contract revolver is a later version of Smith & Wesson’s .45 Hand Ejector U.S. Army Model 1917, itself having evolved from the 44 Military Revolver, and that from the Hand Ejector First Model of 1908. When American outrage finally overcame American isolationism to thrust us into the First World War, it was already apparent that there weren’t enough Model 1911 pistols to equip all our armed forces. On the eve of war, Smith & Wesson suggested to the Army that its 44 Military Revolver could readily be made to fire the 45 ACP service cartridge; the War Department gave them the thumbs-up, and Smith & Wesson subsequently built the double-action .45 Hand Ejector US Army Model 1917 on the square butt, five-screw N frame. Manufacture of Smith & Wesson’s original 153,311 Model 1917s ran from April 1917 to December 1918 (Colt also produced about 151,700 Model 1917s during this same period, being large New Service revolvers adapted to the 45 ACP cartridge).

The Brazilian crest on the side plate immediately identifies the Brazilian contract revolvers, all built in the United States and shipped to Brazil in two batches of 1937 and 1946.

The Model 1917 served again in World War II as a “Substitute Standard” to augment the approximately 700,000 Model 1911 and 1.9 million M1911A1 pistols used throughout that war. Though originally blued, some Model 1917s were Parkerized for use in World War II. The Army and Marine Corps issued Model 1917s mostly to military police and artillery and mortar companies in lieu of Model 1911/1911A1 pistols, and I believe the Navy had a few, too. If you’re a student of World War II history, you’ve likely seen the occasional period photograph of an American soldier with a holstered or drawn revolver; if it was issued and not a rare and unauthorized personally owned revolver, it is almost certainly a Model 1917 (though the Navy also fielded other revolvers).

Smith & Wesson stamped a small version of its logo on the revolver’s left side.

Model 1917 revolver cylinders accept rimless 45 ACP cartridges. The same, of course, as used in the 1911/1911A1 pistols. Which were issued mounted in a pair of three-round half-moon clips. These half-moon clips aren’t really required in order to fire 45 ACP in the Smith & Wesson Model 1917 or Modelo 1937, as Smith & Wesson machined a shoulder at the front of the chamber, as found in the Model 1911 chamber, against which the cartridge mouth stops. Colt Model 1917s also had this feature only after Colt manufactured the first 50,000 or so revolvers. Even so, the clips are needed for positive, reliable cartridge case extraction as the extractor cannot engage the rimless 45 ACP case, though empties can sometimes be “dumped” by pointing the muzzle skyward and shaking the revolver. One might also use the rim of a cartridge case to pry fired cases from the cylinder.

The clips, then, are necessary for rapid reloading and reliable extraction. In 1920, when the U.S. government began selling thousands of the revolvers as surplus following World War I, the Peters Cartridge Company introduced the 45 Auto Rim cartridge, a rimmed version of the 45 ACP, specifically for the Model 1917 in order to eliminate need for the clips. Remington soon followed suit. Performance of the two cartridges is identical, and load data for the 45 ACP can be used to handload the 45 Auto Rim.

Other markings include the patent date on top of the barrel…

…and the maker, “D.A.” for Double Action and caliber on the barrel’s left side.

With who knows how many Model 1917 revolver frames and parts still on hand, all that tooling already in place, and the War to End All Wars no longer needing provision, Smith & Wesson tried dressing the Model 1917 in civvies. They produced a target model and a commercial variant, but sold so few that collectors today consider both rare. A few police departments bought the commercial variants, but the only large contract for Model 1917s, other than the U.S. government, came from Brazil.

Brazil first contracted for 25,000 of these revolvers in 1937. These “Brazilian contract” revolvers bear the Brazilian crest on the side plate (right-hand side), with “1937” stamped below, which is the model number Brazil assigned the contract revolvers, known there as the “Modelo 1937.” Smith & Wesson built many, most or perhaps all of these (information resources vary or are unspecific) on 1926-era flat-top frames with squared notch rear sights grooved into the top strap. In 1946, Brazil contracted for nearly 12,000 more Modelo 1937s; for these, Smith & Wesson dug surplus World War I-era frames featuring rounded top straps and U-notch rear sight grooves out of a back room somewhere.

The Peters Cartridge Company developed the 45 Auto Rim cartridge specifically for milsurp Model 1917 revolvers. Remington manufactured the cartridge, as well.

The 45 Auto Rim (right) is simply a 45 ACP (left) with a rim. Half-moon clips added thickness to the 45 ACP rim.

In addition to the Brazilian crest and “1937” stamped on all Modelo 1937s, Smith & Wesson also stamped a small version of the company trademark on the left side, and “MADE IN U.S.A.” on the frame’s right side, above and forward of the trigger guard. These latter two stamps don’t appear on the U.S. military Model 1917.

A “S.&W. D.A. 45” stamp appears on the left side of the 51⁄2-inch barrel, and typical patent dates are stamped on top. Some of the first Brazilian contract revolvers with post-War commercial barrels were marked: “SMITH & WESSON” on the right side. Barrels later replaced by the

Brazilians bear, “FABRICA DE ITAJUBA Rv .45 M1917” (Indústria de Material Bélico do Brasil of the city of Itajuba) or “I.N.A.” (Industria Nacional de Armas, National Arms Factory) stamps, also on the right side.

Apparently, some Modelo 1937s, probably from the second contract, lack a lanyard ring, and the hole pre-drilled for it is instead plugged. On the revolver presented here, a six-digit serial number is stamped on the butt behind the lanyard ring, and also inside the right wooden grip. The cylinder crane and its recess on the frame bear matching “82583” stamps, presumably assembly numbers. Some Modelo 1937s are reported to bear a “REG. U.S. PAT. OFF.” stamp on the trigger guard and/or hammer, but on this revolver, the mark accompanies the company’s trademark on the left side.

The hammer spur is checkered, the trigger face is serrated (it is smooth on the Model 1917), and both are color-case hardened. While some Modelo 1937s wore checkered grips with Smith & Wesson medallions, others, like the one here, have smooth wooden grips, as did most U.S. military Model 1917s.

Remington’s 45 Auto Rim headstamps are not abbreviated.

Most Modelo 1937s fell within two serial number blocks, and the keyword here is “most” because there are many known examples among both contracts with serial numbers well outside those ranges. The revolver here is one of them. This would seem to indicate that Smith & Wesson was doing a bit of housecleaning of Hand Ejector N frames to fill the Brazilian contracts, or perhaps there was some administrative reason for the anomalous serial numbers. Why some of these Modelo 1937s have serial numbers outside the serial number blocks is not known for sure.

Two features of this particular Modelo 1937 indicate with confidence that Smith & Wesson built it for the second Brazilian contract in 1946. First and most interesting is that the serial number on the butt is read right-side up with the barrel pointed to the left; all pre-World War II Smith & Wesson hand ejectors had serial numbers read upright when the barrel is pointed to the right.

Except for the first 50,000 Colts, all Model 1917s, including the Brazilian contract revolvers, have ledges in the chambers on which 45 ACP case mouths stopped to prevent cases from moving forward when struck.

Second, the frame is World War I surplus, as indicated by the U-notch rear sight and the lack of a hammer block. The latter first appears in Model 1917s in 1919 at about serial number 185,000, which is well beyond the serial number of this particular Modelo 1937. So, here we have

a World War I-era surplus frame bearing a serial number outside the two serial-number blocks, stamped after World War II, and bearing the Brazilian crest. The Modelo 1937 followed the Model 1917 into combat when Brazil declared war on the Axis powers in 1942 and sent a 25,000-man expeditionary force to fight against the Nazis in Italy in 1944. Though outfitted by the U.S. Army in Italy with the same weapons used by the U.S., apparently, some Brazilian officers preferred their Modelo 1937s over the M1911 service pistol and brought their revolvers with them.

Remarkably, Modelo 1937s remained in service with Brazilian military and paramilitary forces into the 1970s, when they were finally supplanted by semiautomatic pistols. Following World War II, the U.S. government supplied Brazil with the tooling to manufacture its own M1911A1 pistol, the “Automatico pistola M/973,” which it first made in 45 ACP, then in 9mm Parabellum. This pistol, in turn, was supplanted by the Beretta Model 92, and today the Glock pistols are the choice for Brazil’s forces.

This Modelo 1937 returned to the USA via importer Century Arms International of St. Albans, Vermont,

as indicated by the stamp on the frame under the left grip, in 1989-1990, when Brazil sold the revolvers as surplus to a number of different US importers in conditions ranging from fair to excellent. This one rates “NRA Excellent” condition. There’s some holster wear at the muzzle, but the rest of the bluing is pretty much intact, and the revolver functions properly and locks up tight, so one could consider it a shooter as well as a collectible.

Post-World War II Hand Ejector serial numbers are read upright with the barrel pointed to the left. The serial number on this Modelo 1937 is one of the few that fall outside the two blocks of numbers that went to Brazil (the last two digits are digitally removed here).

Though its diet staple is, of course, standard factory 230-grain FMJ

bullet loads launched at about 830 feet per second (fps), and one would expect that at least some factory-loaded 230-grain FMJ ammunition should shoot to point-of-aim between 15 and 25 yards, there’s no reason why a handloader should be limited to that. Lead bullets are perfectly appropriate in the revolver, and some experimentation will find loads that will shoot to point-of-aim with the Modelo 1937’s fixed rear sight. One of my long-time favorite handloads for 45 ACP/45 Auto Rim has been a relatively mild 200-grain lead semiwadcutter over 5.2 grains of Wincheser 231. The accompanying table listing some suggested loads are maximum loads not to be exceeded; as always, start with reduced charges and work your way up while watching for signs of excessive pressure.With perhaps 37,000 Brazilian contract revolvers manufactured, they aren’t extremely rare, though who says what number of guns among any particular model delineates the points between being “Extremely Rare,”

“Rare,” “Uncommon,” and “Ho-hum”?

Yet, the number of surviving examples is unknown, so it seems reasonable to me that this Modelo 1937, therefore, qualifies as “Uncommon” when I bought it, and is “Rare” if I ever sell it.

I’m not a serious collector of Smith & Wessons (or of anything, for that matter) if by “serious” we mean striving to obtain every nuanced example of a thing, be it butterflies or Ballards. Rather, I suppose I am a casual repository of history as recorded in the firearms that bear witness to events and people that now seem dead and gone, but that are actually quiescently stored within an old revolver.

.jpg)