Walnut Hill

Inflation: Pluses and Minuses

column By: Terry Wieland | March, 26

One of the lesser-known features of the internet is the inflation calculations that tell you what a price from 1880 would be today, given inflation over the past 145 years.

This is useful when you’re saddled with someone bemoaning the fact that he was not around when you could buy a pre-’64 Model 70 for a hundred and twenty bucks or some such. There seems to be a complete disconnect on the part of these guys, who conveniently forget or never knew that when the long-ago Model 70 was going for that, they might have been making only 50 dollars a week.

Obviously, such calculations are not exact, but they are useful to put things in perspective, and I can report that, by and large, the rifles and pistols we buy today are, in historical terms, at least comparable, if not actual bargains.

The same is true of optics, and by coincidence, a press release just landed in my inbox announcing the debut of a new GPO (German Precision Optics) spotting scope: a 16-48x65 with a retail price of $839.99.

In 1965, the year I bought my first Gun Digest and set my feet firmly on the road to perdition, a Bausch & Lomb“Balscope” 15-60x60 with an angled eyepiece listed at $159.50. In 2025, according to my inflation calculator (USInflationCalculator.com)that translates to a whopping $1,644.62! That’s almost twice the price of the GPO, and the new one is so much better than that ancient Bausch & Lomb; there’s simply no contest.

All right, you say, but that’s an unfair comparison. Optical quality has improved so much over the last 60 years through technological advances – the glass, grinding, weatherproofing, durability and ultra-precise computerized production machinery. Of course you’re right, but the fact remains, today you get far more for much less.

Let’s look at a rifle. Last September, at Rock Island, I lucked into a Ballard “Union Hill” No. 8, in wonderful condition. In the late 1880s, it retailed for $34. Today? That thirty-four bucks would be $1,159.00.

Marlin put a lot of hand labor into its Ballards, and the blank for the walnut stock alone would set you back upwards of a grand. As well, such skilled hand labor is more expensive today. However, for that money, you can get a well-made, modern rifle that will accept a scope and is at least as accurate. We’ll call that one a draw.

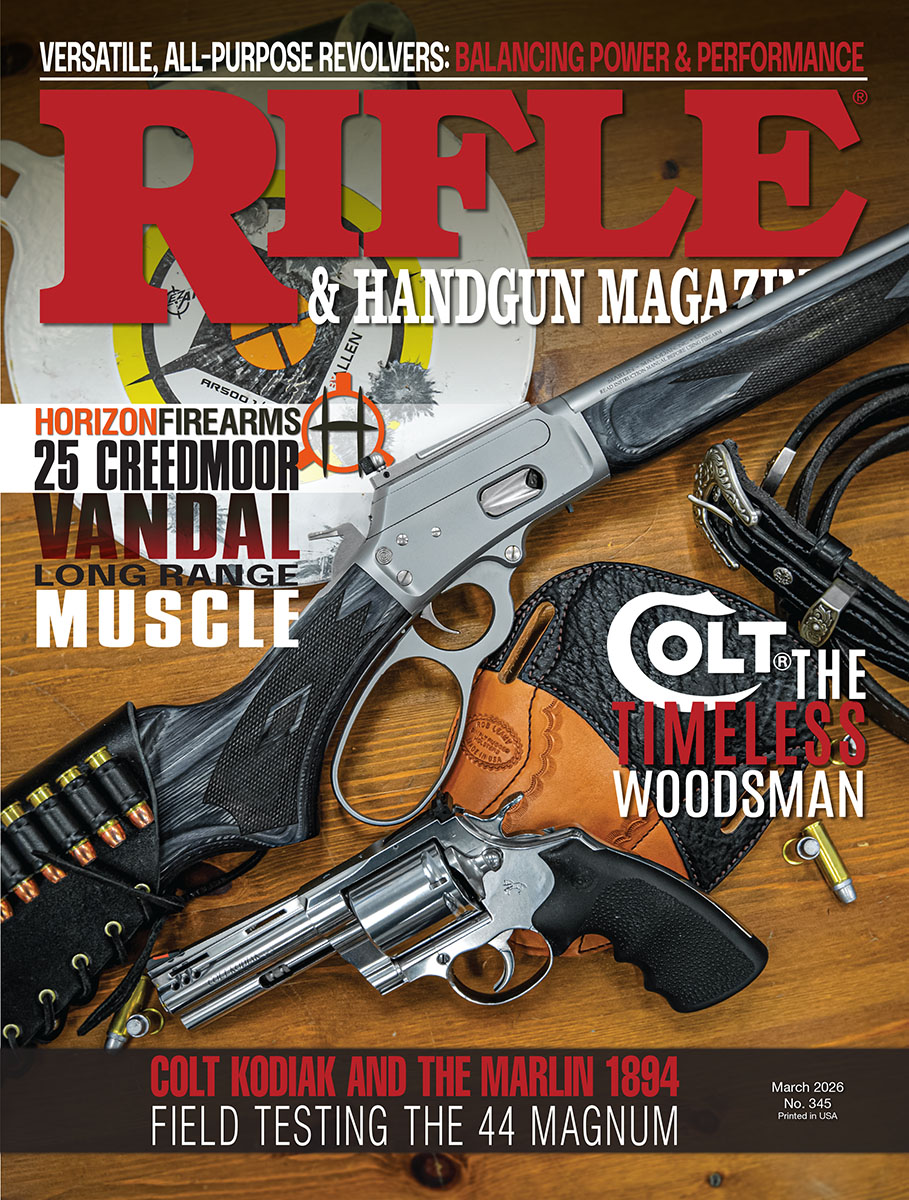

Let’s try a pistol. In 1950, a sweetheart year for the Colt Woodsman, a long-barreled standard target model retailed for $70, according to that year’s Gun Digest. Today, $70 would be $943. Tony Galazan’s Standard Manufacturing Company, sister company to Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing, makes a clone of that Woodsman called the SG22, whose quality is every bit as fine, and sells for $1,299. Not a huge difference.

Another way to look at this is to compare the average wage from way back when with the price of a rifle. This is even more iffy, given that there was then, as now, a wide range in incomes for working people. Here, though, I can give some exact figures because my income in 1968, when I started in the newspaper business, is engraved on my memory. As a copy boy on a mid-sized daily, I made $48.50 a week. Shortly thereafter, I struck a deal for a Sauer Royal side-by-side 12 gauge, used, on terms – terms! – for $125. My father, who owned a travel agency, drew about a hundred a week.

Today, a thousand a week is mid-range for most of us, so for three weeks’ salary, give or take, Tony Galazan will sell you one of his excellent Revelation over/unders or lower grade side-by-sides, and I can tell you they are every bit as good as that Sauer. (For the record, the Sauer was solid as a Leopard tank and handled about the same way.)

Here’s another recollection: In 1977, Abercrombie & Fitch, the late lamented gunshop in New York, would order you a Purdey for $2,700. No, seriously, and I have a 1977 catalogue to prove it. Today, $2,700 would be $14,471, which would be little more than a down payment on a second set of barrels. For Purdey, in London, the cost of everything has far outstripped inflation, and has for a long, long time, in spite of the collapse of the pound Sterling against the U.S. dollar.

At various times over the past 30 years, there have been attempts to resurrect the great old American single-shot rifles. Browning brought back the 1885 as a factory product, the Sharps came back twice and stayed once, the Ballard made a brief reappearance, and the Stevens came and stuck around under the aegis of CPA. Except for the Browning, these are mostly custom propositions with all the attendant opportunities to drain your bank account for upgraded walnut, engraving and special features.

This being the case, it’s hardly fair to compare them to what you could get 140 years ago, except for the fact that many rifles back then were also custom and could be had with virtually any feature you wanted, many of which were no extra charge.

Again, the availability and cost of skilled labor has played a huge part in rising prices, and escalating prices for the best walnut have been right in there as well.

One of my regrets is that, in 1976, I could have bought a Krieghoff skeet special with four sets of barrels, in a fitted case, for $2,800, which of course I didn’t have. That, you’ll notice, is comparable to the Purdey mentioned above. Krieghoff, which has embraced CNC technology in a big way, would not sell me that gun today for fourteen grand, but I could get an awfully nice one for something close. A K-80 trap combo with two sets of barrels, retails for about $18,000, with most of the K-80 variations listing around $12,000.

Which brings up another point: List prices in Gun Digest are seldom what you pay at street level. Competition for gun sales is intense, margins are vapor-thin, and with few exceptions, you can almost always get a factory gun for less than suggested retail.

Let’s go back to my original example, the Winchester pre-’64 Model 70. I grant you, much has changed since 1960, when the pre-’64 was at its finest. Winchester Repeating Arms is long gone, replaced by U.S. Repeating Arms and later folded into Browning. As for the Model 70 itself, first it was bastardized in 1964, then modified, then modified again in 1993, back to something resembling the pre-’64.

Leaving aside the can of worms which is collector value, in my opinion, if you buy a Model 70 today, you will get a better rifle in almost every way than you would have in 1960, and it will cost less. In 1960, a standard grade Featherweight was $130. Today, that $130 is $1,469, while a new Model 70 Featherweight is $1,399. I have one of those new-production Featherweights in my rack, along with a couple of nice pre-’64s, and quality-wise there is nothing to choose.

Were I to go to town with some ultra-exact digital measuring instruments, I bet I’d find the tolerances on the new rifle considerably tighter, and no Model 70 ever left New Haven with a bolt this smooth. Since you asked, the walnut is about the same quality, although the old ones are American black walnut and the new one comes from Europe.

Overall, if someone put a gun to my head and demanded a definitive answer, I’d say we’re better off today, in terms of gun prices, than they were in days of yore. They may have had more animals and open country, but we have better dentistry. It all evens out. Sort of.