The Colt Woodsman Match Target

Love at Second Sight

feature By: Terry Wieland | March, 26

There’s only one Woodsman in our hearts, at least, if not strictly in history. Our Woodsman is the Colt .22 made from 1927 to 1977, and one of the few true icons in the world of guns. It was born into a world of bathtub gin and Al Capone, and died in a welter of sky-high oil prices and worldwide inflation, but what a half-century it had!

During its 50-year life, the Woodsman went through several iterations, later characterized as series one, two and three. Some improved its function, some reduced its cost, some simply made it look more modern, but right up to the end, the Woodsman never lost its allure.

For that matter, there is a whole class of .22 semiautomatics that resemble one another, including the High Standard line (founded in 1926 by Gus Swebelius) and the Ruger .22 that Bill Ruger launched in 1949. In some cases, the resemblance is purely cosmetic, as in the grip angle of the Ruger.

This may seem like a minor concern, but it’s worth exploring. During the twentieth century, two main approaches to grip angle emerged and became dominant. First was the Luger in 1908, then came the Colt 1911. The Luger was angled more sharply to the rear; the 1911 was more vertical.

The 1911 won out in the end because of its role in American bullseye shooting, and a desire by competitors to have grips that were all similar. Nothing was going to change the 1911, so the .22 had to, and eventually that happened, but not without a fight.

Col. Charles Askins served with the Border Patrol during the 1930s and was the national pistol champion, among other accomplishments. In The Pistol Shooter’s Book (1953), he condemned the 1911 grip as “unnatural.” He insisted the Luger’s grip was superior, indirectly endorsing the Woodsman’s grip, which at the time was the most popular pistol for shooting the bullseye rimfire class.

Different designs all have their admirers, and the arguments have started more than one fistfight, but not even the most rabid 1911 admirer would deny the Luger’s angled grip is attractive and feels good. This graceful appearance adds much to the appeal of the Colt Woodsman, and nowhere more so than in the Match Target model, introduced in 1948 and continued until 1977.

During the Second World War, most gun manufacturers ceased civilian production, and the resumption after 1945 saw many old models dropped and others redesigned. The Woodsman was modified in many ways, and this became the “series two.” Changes included a thumb-latch magazine safety similar to the Colt 1911, an automatic slide stop, magazine safety and a longer, heavier frame.

The Match Target was available with either a 4½- or 6-inch barrel and was intended to renew Colt’s domination of bullseye shooting in the rimfire class.

Col. Charlie Askins, never known for pulling punches or stifling an opinion, was not all that impressed. He felt the Woodsman had lost ground against its competitors and was now an old-fashioned design compared to, for example, the new Smith & Wesson Model 41 and, particularly, the High Standard Supermatic.

“The High Standard Supermatic Trophy is the finest .22 caliber handgun,” he stated flatly.

Askins noted that, in 1940, 34 out of 48 pistols used by the top shooters were Woodsmen; a similar survey in 1952 named the High Standard first (with nine), followed by the Ruger (with six) and the Woodsmen (with two). Not exact, perhaps, but meaningful.

Askins called for a complete updating of the Match Target. This occurred in 1955 with the launch of the series three pistols, but in reality, not much changed. The magazine release was returned to the heel of the grip, where it had been originally, and there were minor changes to the sights and grips.

By that time, with High Standard in full swing, Smith & Wesson getting into the act with the Model 41, and Ruger becoming a dominant name, the Match Target had simply been left behind.

All of which is not to say it’s not a first-rate pistol in more ways than one.

First, the period from 1946 to 1960 is really a sweet spot of post-war gunmaking in America. Demand was high, innovation was occurring everywhere much of it for the best, and the quality of materials, workmanship and production standards were at a peak.

I have never owned a Ruger, although I have shot many, but for some years I was a semi-serious collector of High Standards, and I have owned four Brownings – two Challengers and two Medalists. Both the Brownings and the High Standards have the advantage of instantly interchangeable barrels. What’s more, High Standard offered all kinds of options in terms of models, barrel lengths and weights, muzzle brakes, adjustable weights and grip configurations. In the 1950s and 1960s, if you liked a lot of choices, the High Standard was your gun.

That at least gives me a basis for comparison, and the Match Target shines in several ways.

First, the grip fits me like a glove. Holding the gun in my hand, I can reach both the safety and the slide release with no effort at all. Both are within easy reach of the thumb rest. The 1911-style magazine release is slightly more difficult because the rest gets in the way, so you can’t change magazines as quickly as with the 1911 itself.

Early Woodsmen wore grips made of Bakelite with distinctive red and black swirls. Later, Colt offered walnut grips as an option. Bakelite is historically interesting in itself, being the first commercial plastic, patented in 1907, and there are even Bakelite collectors.

Balance-wise, Match Targets of both barrel lengths feel good, with the muzzle-heavy quality that Col. Askins insists is vital in a target pistol. Where the High Standard has an advantage, and also the later Brownings, is being able to adjust the balance point by adding or removing weights, and positioning them just so. Not being an Olympic-level shooter, this is of dubious benefit to me. I don’t need any more excuses or opportunities for fiddling; I do enough second-guessing as it is.

After the gun fit itself, trigger pull is, to me, the single most important factor in how well I shoot, and it doesn’t matter if it’s a shotgun, rifle or handgun.

The feel? The silky feel of polished carbon steel is legendary, giving any gun an eager, cooperative quality. Using them becomes a pleasure in itself, and the Match Target is no exception. No resistance, no grating, no argument. Love ’em.

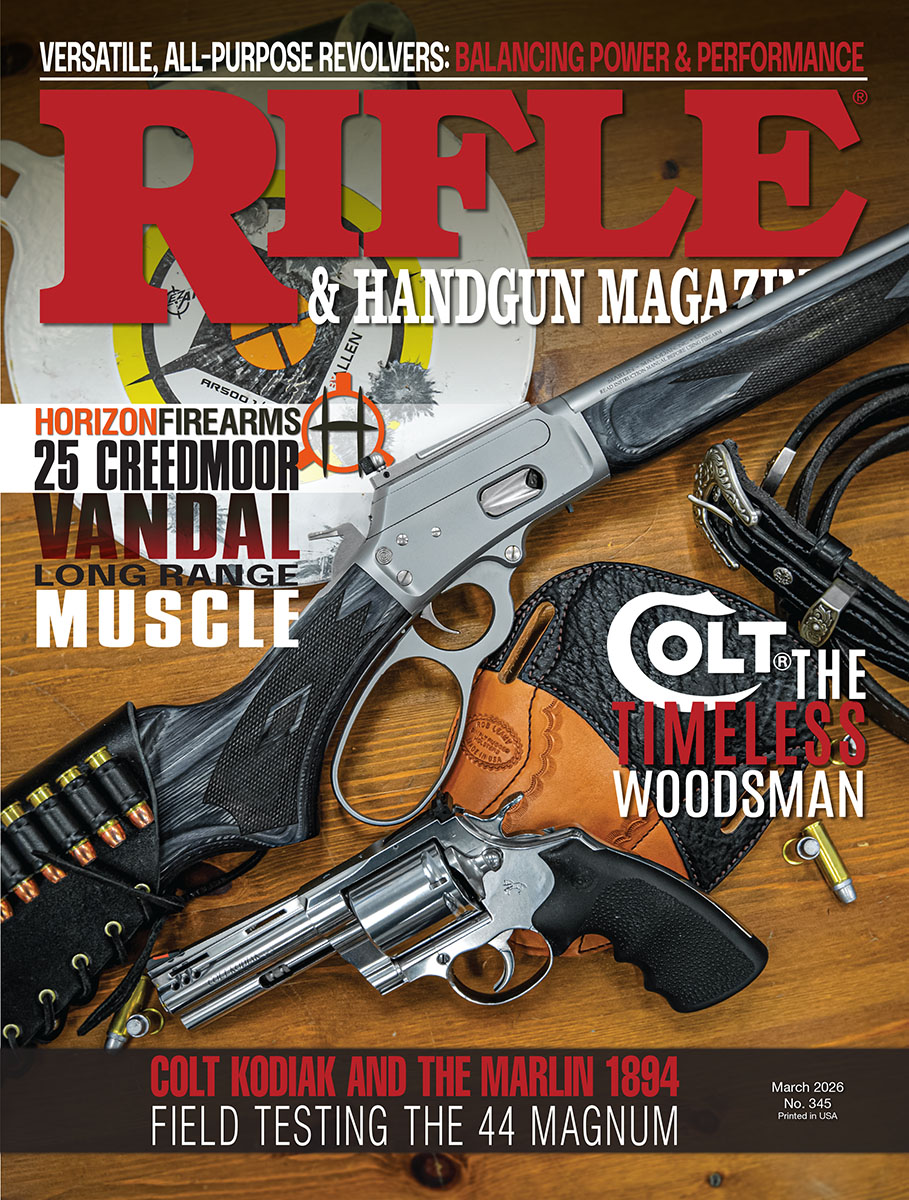

Two Match Targets are shown here. The short-barreled one is beautifully engraved with gold line inlays. This was done after the gun left the factory; had it been a factory engraving job, I could have done nothing more than admire it and drool, but its after-market status eliminated serious collector interest.

Another odd feature of the Match Target is its magazine, which is fitted with a different shape of slide button. Known as the “tombstone” magazines, they are peculiar to the Match Target and originals now bring two to three hundred dollars.

A few years ago, Tony Galazan began making a Woodsman clone, the SG22. Tony owns Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Company, maker of the A.H. Fox and Parker Reproduction, among others; a subsidiary, Standard Manufacturing, produces a number of other guns, including the SG22. Tony being Tony, he decided to equip it with tombstone-style clips, and it works just fine in both my Match Targets.

The SG22 is available in two grades, one with high-polish bluing and the other case colored. In every regard, they are the equal of the series-two Woodsmen, after which they are modeled. They range in price from $1,500 to $1,700, which is considerably less than you would pay for an original in as-new condition.

Maybe it’s the Colt name, maybe the connection with John M. Browning, but the Woodsman is the only pistol of its type that can really be called iconic. Woodsman collectors may disagree, but to me the series-two Match Target is an icon within an icon: It symbolizes everything admirable about post-war American manufacturing.

The Woodsman has even appeared in literature. Ernest Hemingway admired it greatly and wrote about it in several articles, while Raymond Chandler, creator of the private eye Philip Marlowe, armed a hit man with a Woodsman in one of his short stories. According to legend, real-life assassins were equally admiring.

The Colt Woodsman may have been left in the dust later, in the whirlwind of inflation, computerization, alloys, synthetics and foreign competition that killed so many American products, but that does not make it any less a great pistol.

There are more accurate handguns around now, but none that feel better in the hand. That counts for a lot.