Down Range

45 Gov’t/45-70 Success

column By: Mke Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | May, 23

d

The 45 Gov’t didn’t just appear on the scene as someone’s brainstorm. It was introduced after considerable testing, which also included .40- and .42-caliber cartridges. Case shapes of straight versus bottleneck were tried. When the smoke cleared, the top scoring round had a bullet of 1.11 inches, cylindrical in shape, topped with a round nose weighing 405 grains. The diameter of these swaged (not cast) bullets was .458 inch with an alloy of 12 parts lead with one part tin by weight. Upon the bullet were rolled five cannelures .03-inch deep. They were .075-inch wide and spaced .05-inch apart with the bullet having a “dished cavity in its base” i.e. hollow base. A lubricant consisting of eight parts bayberry wax and one part graphite was applied to all five cannelures.

All details in the previous paragraph were taken from the book Trapdoor Springfield by M.D. “Bud” Waite and B.D. Ernst (1980). Furthermore, the book states, “Attesting to the fine accuracy of the No. 58 cartridge was the fact that it was fired in six 20-shot targets at a range of 500 yards resulting in “absolute mean deviation” of 8.58 inches. That beat previous records at either Springfield Armory or Frankford Arsenal. This book does not state whether there was any cleaning of the rifles’ bore during the 20-shot strings. I especially find the case length of 2.035 inches interesting as today’s standard 45 Gov’t (45-70) case length is 2.10 inches. My thought is perhaps those government testers recorded the length of the case from the top of the flange (rim) instead of its bottom. (My current batch of Winchester 45-70 cases have about .68-inch rim thickness give or take a thousandth or two.)

From 1874, when new .45 rifles and carbines began arriving in the hands of both infantry and cavalry troops, they fought in nearly every altercation with Indian tribesmen thereafter and were even used by American volunteer troops in Cuba during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Therein, 45 Gov’t black-powder rounds were fired at Spanish troops shooting back with smokeless powder 7x57mm Mauser rifles.

So what did the new 45 Gov’t trapdoor rifles and carbines displace in the U.S. Army? Until the Model 1873s appeared, infantrymen carried nearly identical trapdoors chambered for 50 Gov’t (50-70). Those used 450-grain bullets over 70-grain powder charges for a velocity of 1,250 fps. The 45 Gov’t 405-grain bullet at 1,350 fps was considered significantly better by 1873 standards. Cavalrymen in 1873 mostly carried Spencer seven-round repeating carbines albeit their hammers had to be manually cocked for each shot. Post-Civil War Spencer carbines chamber the 56-50 round with a 350-grain bullet over 45-grain powder charge. Some cavalry officers disagreed with giving up their repeaters for single shots. In light of the 1876 debacle at the Little Bighorn, perhaps they were correct. Regardless, in a production period of 20 years, the government-owned Springfield Armory produced more than a half-million trapdoors of all variations. By 1875, commercial rifle makers “discovered” the 45 Gov’t and built unknown thousands more rifles for it. Such were Remingtons, Sharps, Ballards, Winchesters, Marlins and more.

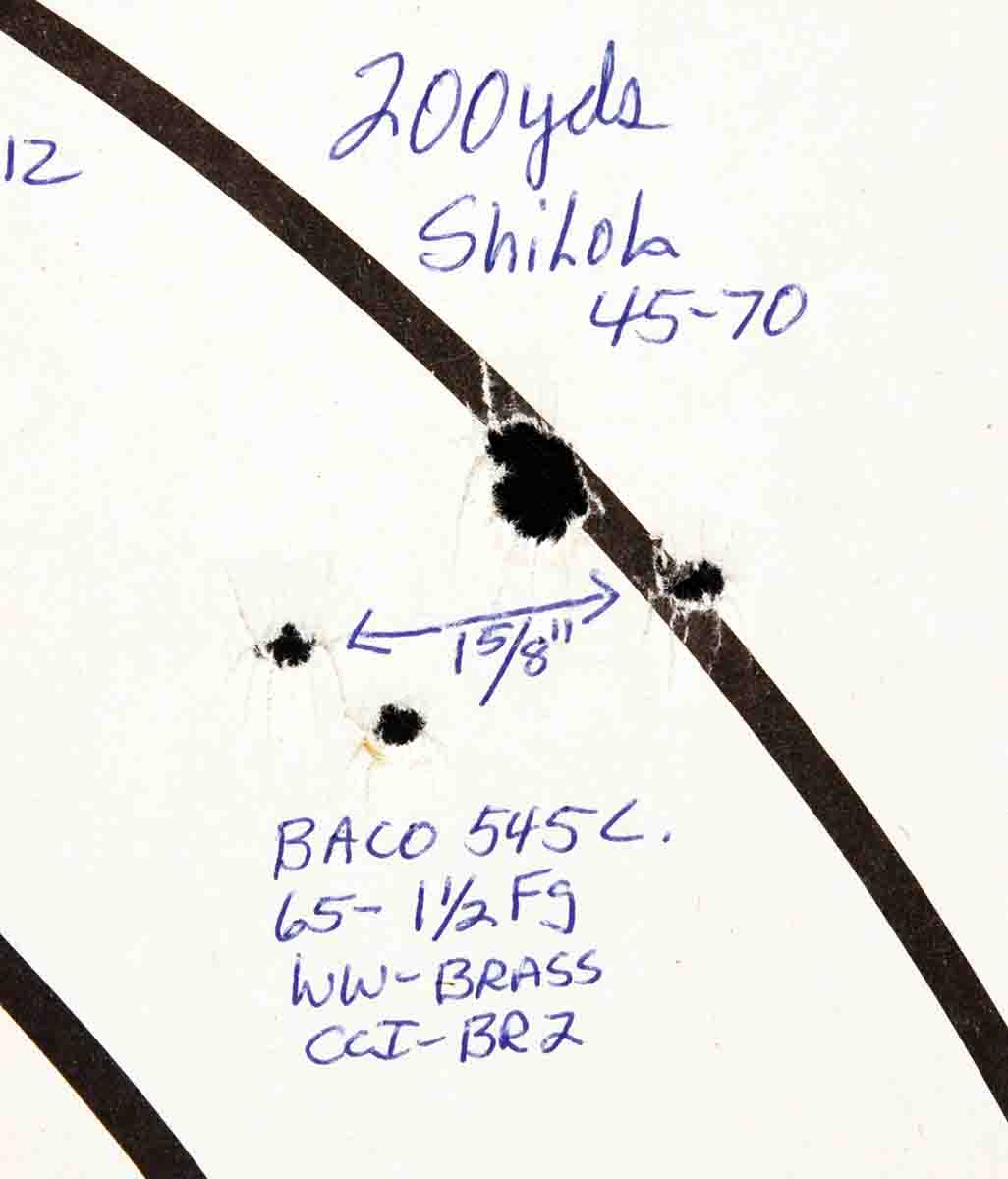

Silhouette in 2008 using a Shiloh 45-70 and I’ve shot beasts from tiny Texas whitetail deer to huge, free-roaming bison with 45-70s.

So how is the 45-70 faring now a full 150 years later? I’ve been told by both Shiloh Rifle Manufacturing and C. Sharps Arms folks that they sell about 10 rifles chambered for 45-70 for every one chambered in any of the other cartridges. Take note about which Marlin leverguns Ruger began offering again after acquiring the former company. They put a line of Model 1895 45-70 hunting rifles in production before any other models or calibers. Henry Repeating Arms has 45-70 leverguns now. There have also been many thousands of Browning/Winchester Model 1886s coming from Japan for almost 40 years and more recently from Italy.