.30 Carbines

Shooting Samples from Inland Manufacturing Co.

feature By: Mike Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | July, 17

It has been no secret that I hold M1 .30 Carbines dear. In 1965, one of the 250,000 or so sold by the DCM to NRA members for $20 was my first centerfire. It coincidentally arrived right at my sixteenth birthday as a gift from my father. Many more have passed through my hands since, there being two M1s, a counterfeit M1A1 and an M2 (select fire) here now.

Sure, they were despised by many combat troops in both World War II and the Korean War for lack of stopping power. That was with full-metal-jacketed bullets. With softnose bullets or hollowpoints, the .30 Carbine can be downright wicked on tissue –not that I would promote it for anything much bigger than coyotes. Also mentioned often is that M1 Carbines were loved by support troops, because of their 5½-pound weight and 36-inch length.

With more than 6.25 million M1, M1A1 and M2 .30 Carbines made between 1941 and 1945, it would be logical to think the market is flooded with them. Not so: Untold thousands were lost in combat. Hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of the surviving rifles were passed out to other countries as foreign aid; one I owned in the past carried Bavarian police markings. Many of the foreign aid M1 Carbines disappeared forever, but some came back, often in “junker” condition. Such reimports are clearly stamped.

M1 .30 Carbines are now highly valued by collectors if they retain all, most or at least many as-issued parts. Two of the four .30 Carbines here are good examples. Both are in World War II as-issued condition. One is by Winchester, the second most-prolific maker. It is highly valued for the name if nothing else. The other is of Standard Products manufacture – highly valued because that company made only four percent of the total production. Neither of these carbines sees heavy use for those reasons.

Hence, there is a market for new .30 Carbines for shooting, hunting and competition. Currently on hand are two versions made by Inland Manufacturing Company of Dayton, Ohio. During World War II, a company of that name (a subsidiary of General Motors) was the most prolific maker of M1 .30 Carbines to the tune of over 2.6 million, or 43 percent of total production. The company also made all the 140,000 M1A1 folding stock variants.

One of the two new ones I have been shooting over a period of months is an M1A1. It has a heavy wire stock, so it folds to an overall length of 26 inches and weighs 5½ pounds. This was intended for paratroopers and was usually issued to officers, NCOs and members of crew-served weapons teams, such as mortar men and machine gunners. Most M1A1s went to the European Theater of Operations, but I’ve seen a photo of at least one over the shoulder of a Marine on Iwo Jima.

Something that must be understood about M1 .30 Carbines as they were developed in 1941 is that no one in the U.S. Army intended them as offensive weapons. They were meant for self-defense by the types of combat troops mentioned in the above paragraph. As such, they were intended to replace .45 Auto pistols then issued to the same people, because training neophytes to be proficient with a pistol was too difficult. Simply stated, it was logically thought that a hit with a light-caliber carbine was better than a miss with a large-caliber handgun. As is usually the case, there were unintended consequences. Carbines were available in such numbers and their 15-round magazines so appreciated in close-quarters combat that they were common right on the front lines. Also in my research, I’ve read of U.S. Marines fighting on Pacific islands scrounging up M1 Carbines to keep in their foxholes at night due to the danger of “banzai charges” by Japanese troops. The carbine’s handy size and that 15-round magazine were very favored then. Photos exist of Marine Corps infantrymen with a full-size M1 Garand in their hands and an M1 Carbine strapped to their backs.

This fact should also be mentioned: By carrying an M1 or M1A1 carbine, that person was recognized by enemy snipers as being someone of importance. It was tantamount to wearing a sign saying, “I’m an officer, or at least an NCO, shoot me first!” I suspect that alone was more than enough reason for some combat troops to ditch their M1 Carbines for the heavier M1 Garand.

The vast bulk of M1 .30 Carbines issued in World War II were different in detail to those used in the Korean War and thereafter. Toward the end of World War II, M1 Carbines were changed. Their early rear sights were an L-shaped piece of steel with an aperture in each leg. The long leg was meant for 300 yards and the short leg for 100 yards. It was replaced first with a milled, fully adjustable rear sight, succeeded shortly thereafter by a stamped version. By sliding its aperture to various detents, it could be elevated to 300 yards.

A feature that makes it possible to spot (most likely) an arsenal remodeling of the M1 Carbine is the bayonet lug. Until near the end of World War II, they had no such lug. When recalled and fitted with adjustable sights, they also gained the lug. A part change that could only be ascertained up close was the “round” bolt as opposed to earlier “flat” bolts. This was done to strengthen it for full-auto firing in the select-fire M2 version and then carried over to the semi-automatic versions. Both round and flat bolts fit all versions of .30 Carbines.

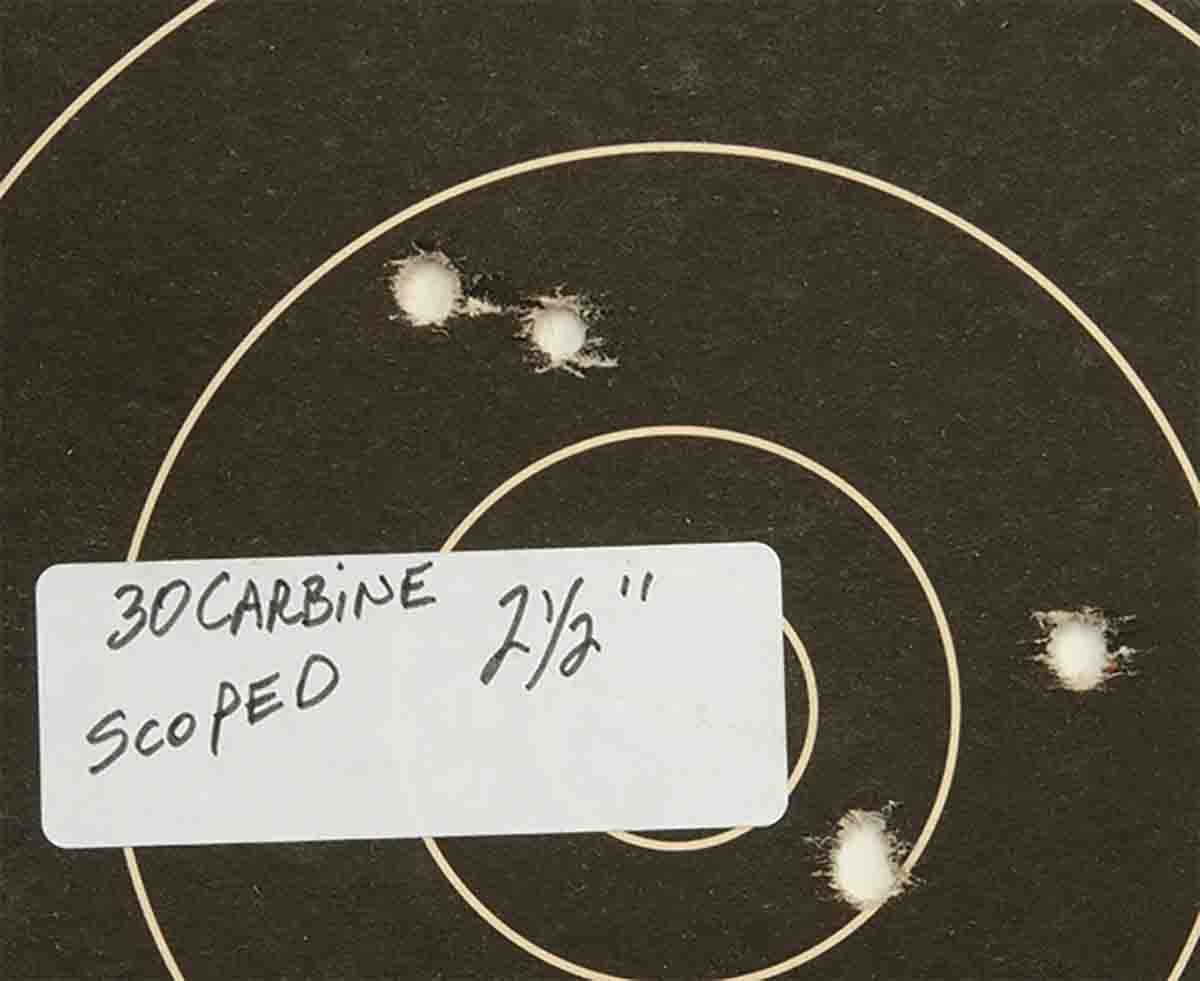

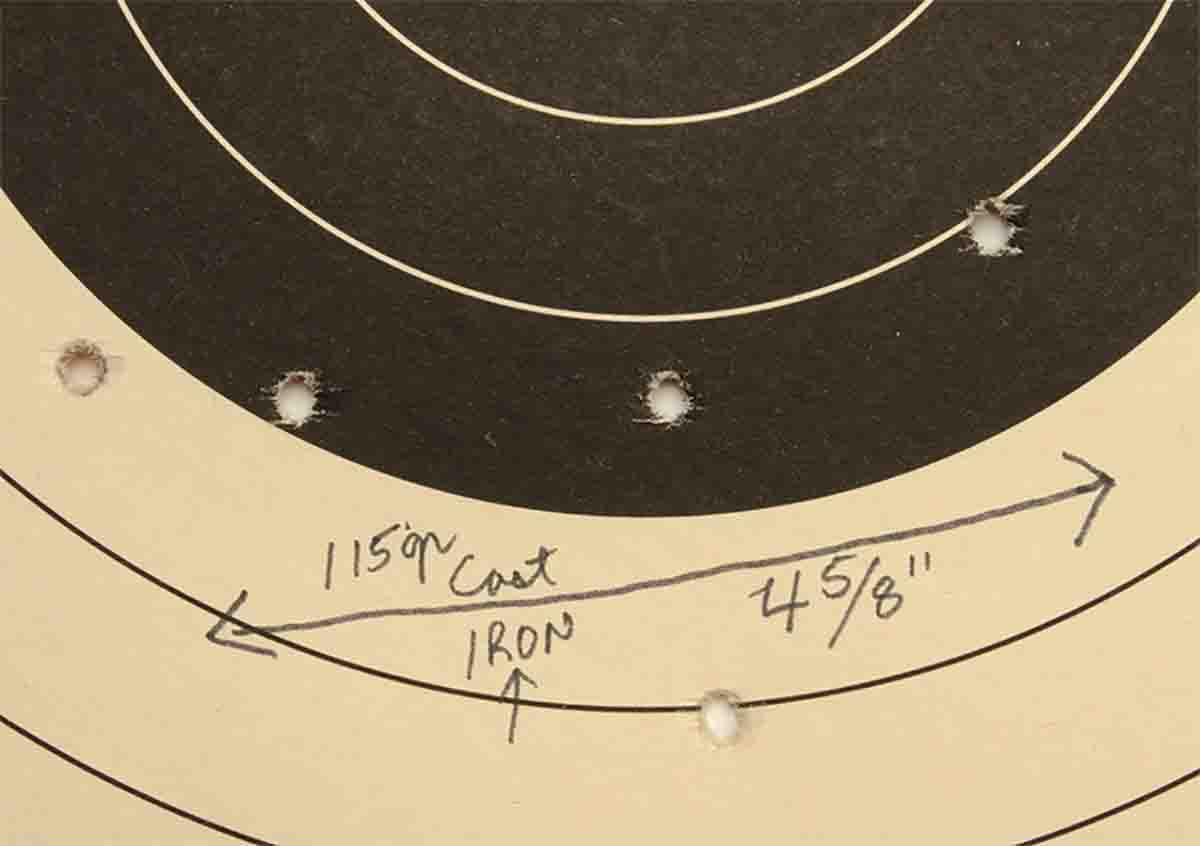

The new Inland M1A1 has the fully adjustable, stamped rear sight – not milled. Its folding stock is a dead ringer for the original. When folded to the carbine’s left side, overall length is 26 inches. As is proper, it has the later round bolt, but interestingly, it has the push-button safety instead of the later rotating design. (The push-button type was discontinued in World War II, due to reports of troops confusing it with the magazine release in the heat of combat.) In my shooting with original, counterfeit and this M1A1, I’ve come to the conclusion that the heavy folding stocks are not an impediment to carbine accuracy. I can hit a 18x24-inch steel plate at 300 yards as easily with the folding stock variants as with full wood-stocked .30 Carbines. That is not to say that 100-yard paper groups are tack-driver level. Most run in the 3- to 4-inch range using the originals and the new Inland carbines.

The second Inland .30 Carbine I have been shooting is not a dead-nuts version of one issued in World War II or Korea. As an aside, most readers my age will remember advertisements in 1960’s gun magazines offering the British bolt-action No. 5 .303, generally termed “Jungle Carbine.” They had a distinctive, flared flash hider at the muzzle. The new Inland outfit has played on that idea by offering its own version of a Jungle Carbine. It also has a distinctive, flared flash hider but is fitted to a 16-inch barrel instead of the standard 18-inch barrel. Otherwise it is a typical issue M1 .30 Carbine regarding its stock and sights. To be totally correct, however, it needs to be mentioned that a flash hider became part of .30 Carbine history with the M3 night-vision version.

Speaking of sights, for most of World War II, M1 .30 Carbines had a post front sight protected on both sides by flared “wings.” From reading and by personal experience, I think it was seldom that M1 Carbines with the early L-shaped rear sight were given to troops properly zeroed for elevation with either aperture. The only recourse is a shorter or higher front sight as the case might be, and changing them is not the simple procedure it is with, say, the Model 1903’s or 1903A3’s sight blades. Changing M1 Carbine front sights requires special tools and time. Conversely, windage zeroing was simple; just drift the sight base laterally as needed.

Toward the end of World War II, when the new windage and elevation sight was developed for all versions of .30 Carbines, it must have been a relief to troops and company armorers. Although .30 Carbines that survived World War II were called in for retrofitting with new adjustable rear sights and bayonet lugs, obviously not all of them made it back to arsenals. As evidenced by my Winchester and Standard Products M1 Carbines, early style examples do pop up occasionally.

Shooting with the Inland Jungle Carbine was on par with the M1A1. To my aged eyes, M1 Carbine front sights are blurry, and the Jungle Carbines’ front posts are even closer. Groups hovered near 4 inches, but I can say that functioning with both samples was initially perfect with several brands of factory ammunition and with jacketed bullet handloads using 14.5 grains of H-110 powder. Switching to cast bullets, a favored load of 14.0 grains of Accurate 5744 and 115-grain gas checked roundnoses from SAECO mould 302 functioned in the M1A1 but would not work the bolt fully in the Jungle Carbine.

After firing many thousands of .30 Carbine handloads, here are a few tips: Despite using carbide-type resizing dies, figure on using case lubricant. Without it, trying to size a case, even in the carbide die, will nearly break the edge off a stout reloading bench. But, most certainly do get a taper-crimp die. No one wants a bullet pushed back on top of the powder charge during its travel up the feed ramp and into the chamber. Stick with 110-grain FMJ or softnose bullets, and don’t try to seat them without flaring the case mouth with a proper die. Finally, trying other bullet weights, or those with much lead core exposed, is usually an exercise in futility.

That brings me to my latest brainstorm. Inland’s new brochure lists a “Black” M1 .30 Carbine. Its darkened stock appealed to me not a bit, but the metal handguard sporting a Picatinny rail most certainly did. With a couple of Leupold Scout scopes on hand, I asked Charlie Brown at Inland to send me one of those handguards. By means of a bracket fitting under the barrel, the rail handguard was put onto the Jungle Carbine along with a 1-4x Leupold scope. Telling a friend about it, he referred to this carbine as “tacti-classic.” Instead of trying to guess about the front sight’s halo, the scope’s crosshairs give perfect sight placement.

Paper target groups got smaller on the whole, but what got distinctly easier was hitting steel silhouettes at distance and/or placing bullets on them in precise spots out to 100 yards. There are many accoutrements for .30 Carbines: slings, oilers, carrying bags, magazine pouches, etc. Originals are getting pricey and have become collectors’ items. I’ve equipped all my .30 Carbines with the same items from a company called World War Supply (www worldwarsupply.com).

The second brainstorm didn’t work out. Swapping the Jungle Carbine barreled action into the paratrooper stock was tried but did not quite fit. So in the near future, I’m going to try adapting the Picatinny handguard to a counterfeit paratrooper carbine. With a scope on it and a folding stock, that might be the handiest, most practical M1 .30 Carbine ever devised.