A Rifleman's Optics

Nightforce for the Long Shot

column By: John Haviland | July, 17

Hunting license holders, as a percentage of the U.S. population, have dropped by nearly half since 1960. It’s estimated that gun owners outnumber hunters five to one. These folks want to shoot their rifles, and an increasing number of them are taking up target shooting, specifically long-range shooting. This popularity is signified by all the tactical “chassis” rifles manufacturers have introduced in the last few years and sniper-style competitions around the country, like the Precision Rifle Series.

Nightforce Optics has been making scopes with a tactical focus for 25 years for these long-range rifles and shooting. Last fall I attended a long-range shooting course sponsored by Nightforce at the CORE Shooting Solutions Center near Baker, Florida (www.coreshooting.com). The CORE site is sort of like a golf course, with a clubhouse and stretches of mowed fairways, except it’s encircled by tall embankments, and bullets hit steel plates instead of white balls. Shooting there does not entail sitting and freezing in the cold or sweating in the sun in hopes of taking a single shot at a passing deer. Shoot all you like, then retire to the clubhouse for an appropriate beverage.

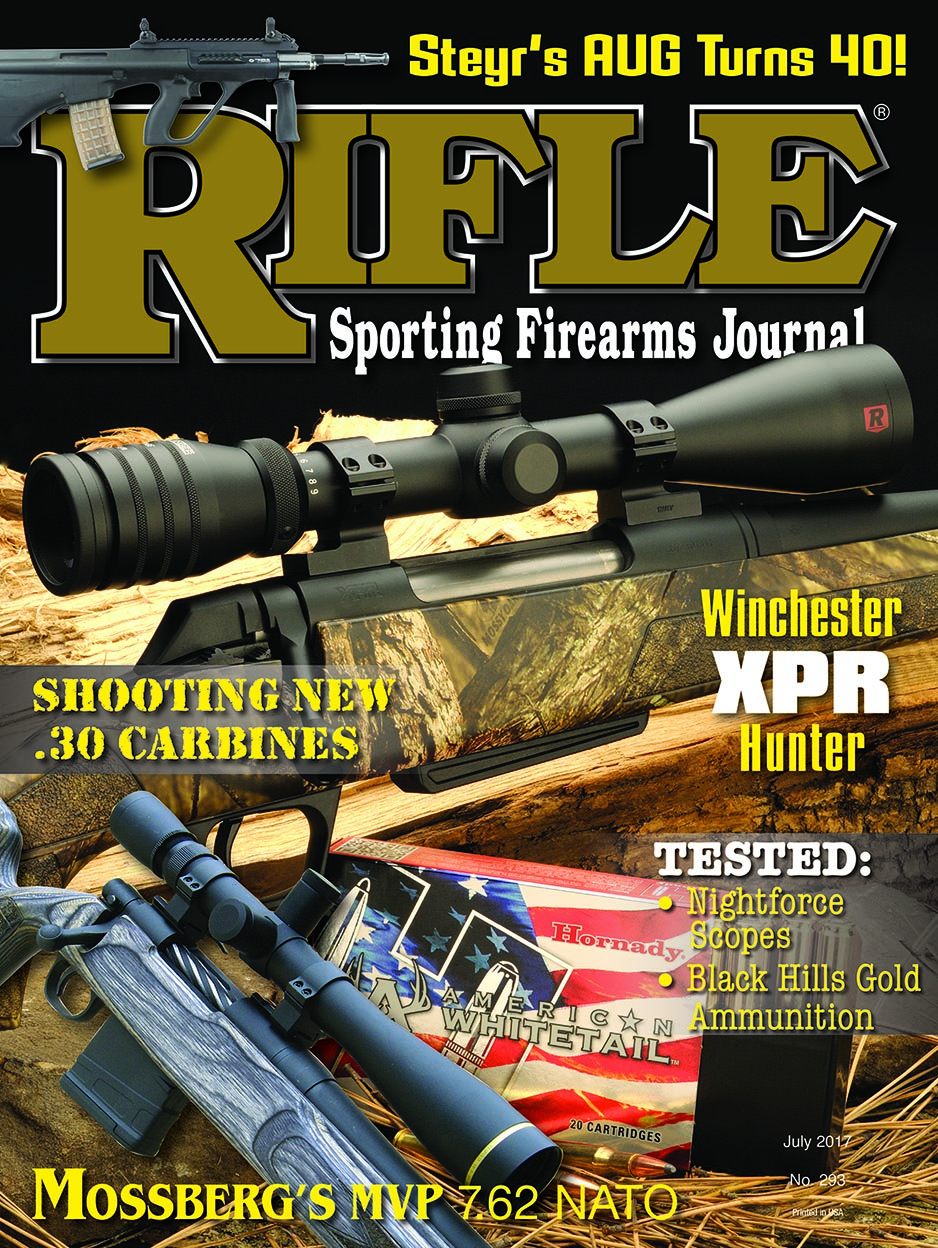

Shooting started with Accuracy International’s Accuracy Tactical bolt-action .308 Winchester rifles with Nightforce ATACR (Advanced Tactical Riflescope) 5-25x 56mm F1, 4-16x 42mm F1 and the 7-35x 56mm F1 scopes. Instructors Bryan Morgan, Terry Cross and Ryan Castle assessed our shooting form with a critical eye.

After firing a shot, my hunting habit is to lift my head off the stock comb to work the bolt and survey the area and game for telling results. Cross coached me to keep my cheek on the comb and continue looking through the scope while cycling the bolt. That saves time between firing the next shot and before the ever-changing wind switches intensity or direction.

Everyone seemed to prefer twisting the elevation turret to compensate for bullet drop at various distances, even though the scopes featured reticles based on minute-of-angle or mil-radian divisions to compensate for bullet drop and drift. The instructors had precisely determined the ballistics of the rifles and loads beforehand and knew exactly how much to dial up the elevation turret on the scopes to aim right on from 100 to 1,000 yards. They called out required elevation adjustments. Wind is the gremlin of long-range shooting. They watched the movement of grass and mirage to judge the wind, called windage correction and yelled, “Send it!”

Steel plates at one station stood at 300, 450 and 550 yards. Shooting prone with the rifles supported on a bipod, we dialed and held for the wind and hit each plate three times from one distance to the next. The elevation turret on the scopes must have been twisted from one end of their adjustment range to the other 100 times during two days of shooting.

The magnification turned up to 25x and even 35x on a couple of the Nightforce scopes. That high magnification provides a more exact look at extreme long range or small targets. One shooting scenario consisted of small steel plates inside the shade of vehicles at 400 to 700 yards. I had to turn magnification to about 20x to distinguish the plates from the dark surroundings. I was shooting with the rifle somewhat less than steadily balanced over a big rock, and the high magnification exaggerated my shake. Plus, mirage was boiling up some and distorted the view. I hit a few – and missed a few.

Mirage increased in the sunlight of midday. Shooting at 1,000 yards, a white plate danced about through the 7-35x 56mm F1 scope set on 25x. The view of the plate was sharp with the scope set at 15x. When I missed the plate, it was to the side from failing to hold the correct amount for the wind.

At another setup, five shots were fired at a plate hidden behind a berm at 740 yards. The idea was to trust the scope’s windage and elevation adjustments. We aimed at a circle of orange clay targets visible high and to the left of the hidden plate. A spotter who could see the concealed plate shouted adjustments. We dialed and shot. Four of my shots arched over the berm and landed in a tight circle in the center of the plate. The final bullet hit the plate but slightly to the right.

To see exactly how a Nightforce scope is adjusted, I borrowed a Nightforce ATACR 4-16x 42mm F1 scope and at home mounted it on a Colt LE901 autoloading .308 Winchester. Sighting it in at 100 yards, several three-shot groups measured a touch under an inch while shooting handloads consisting of 44.0 grains of TAC powder and Berger 168-grain Target Hybrid bullets.

Switching to targets at 300 yards, bright sunlight shined right at me and mirage rose off the snow-covered ground. Targets stood in deep shade. Setting the scope at 12x provided a clear view of the black circles on white paper through all that interference. The first three bullets hit 10.5 inches below aim. The holes were plainly visible through the scope. In fact, the holes were easier to see through the scope than through my 16-48x 60mm spotting scope set on any power.

I could have dialed up the elevation turret to raise bullet impact even with the center crosshair in the scope’s MIL-R reticle, but bullet drop at 300 yards was nearly one milliradian, and the floating center crosshair is 1.0 mil across in the MIL-R reticle. The reticle is positioned in the scope’s first focal plane, so the reticle spacing remains constant at all magnifications. Aiming with the 1-mil hash mark on the lower wire, I fired three bullets into a 4-inch group. Shooting (or referring to a ballistic program) to determine bullet trajectory at different distances and establishing hash marks to compensate for drop at those distances is, in the long run, far quicker than dialing elevation.

All this calculating and shooting in Florida and at home was fascinating and instructive. It put into focus the constant dependence on a scope to hit targets at ever-changing distances. All the shots I fired during those sessions were more than I would fire in years of hunting and would make me a better shot while hunting.