American Anomaly

Mitt Farrow's Controversial Rifle

feature By: Terry Wieland | July, 20

Willard Milton Farrow is not exactly a household name, and when mentioning the Farrow rifle to most shooters today, you get a blank look. Everyone knows Winchester and Remington, the cognoscenti know Ballard and Stevens, and the Sharps is famous for many reasons. The Farrow? Never heard of it.

Just how obscure is it? Frank de Haas, in his comprehensive 1969 book, Single Shot Rifles and Actions, which covers virtually everything American and foreign, does not so much as mention either Farrow or his rifles.

This is not the outcome most would have predicted in 1888, when the rifle first went into production and Milton Farrow was at the height of his fame as a marksman on several continents. Unfortunately for both Farrow and the rifle, while he was a gifted designer and mechanic, he seemed to lack the tenacity and perfectionism that set apart the truly great designers, such as his contemporary John M. Browning, and great dedicated riflemakers like his other contemporary, Harry Pope.

Mitt (as he was known to his friends) Farrow seemed to get one project almost completed, then lose interest and go on to something else. This somewhat scatterbrained approach may well have cost him his rightful place in the annals of American shooting.

Milton Farrow was a superbly gifted target shooter who excelled at every discipline with a rifle – offhand and prone, from 200 to 1,000 yards. He could do it all. The rifle he designed was intended for that purpose only. It was a single shot with a falling block action that could be fitted with a set trigger and was offered either in a hammerless design or with an external hammer. That is the basic outline of its features.

The design was intended to correct what Farrow saw as fundamental flaws in such legendary designs as the Ballard, and no one was in a better position to know what those flaws were than Farrow himself. He had used a Ballard rifle to win major competitions in America, England and across the continent, and was acknowledged to be one of the finest shots in the world. As well, as an employee of Marlin, maker of the Ballard, he had been involved in modifying its design for centerfire cartridges. He certainly knew what a great target rifle needed to be.

Given his early life, it is somewhat surprising that Farrow ended up where he did. Born in Maine in 1848, Willard Milton Farrow (as he was christened) dropped out of college in his teens due to lack of money, apprenticed himself to a watchmaker and had mastered that trade when he read

about the international shooting matches at Creedmoor in 1876. He became interested, bought a rifle and taught himself to shoot. His rise was startling. By 1880, he was winning major matches across the country, even travelling to England to compete, and win, at Bisley. He also won national matches in France and Germany, and newspapers began referring to him as the “world champion.”

Farrow abandoned watchmaking and went to work for the Marlin Firearms Company, which was then manufacturing the famous Ballard target rifles. Farrow was involved both in perfecting the Ballard for the new cartridges then appearing, and spreading its renown by winning matches with it. He designed a Schützen-style buttplate that was referred to as the “Farrow” plate, which was available on Ballards until the rifle was finally discontinued. It is sometimes noted that a “Farrow rifle” is in the Smithsonian Collection in Washington, D.C., and indeed one is. However, it’s his early match-winning Ballard, not a rifle of his own design from later years.

Farrow was a man of many parts. He was a founder and president of the Newport Rifle Club in Rhode Island. After his major successes in competition, he wrote a book called How I Became a Crack Shot; he designed and patented his rifles and set up a company to manufacture them. He designed and produced loading tools. Farrow’s first manufacturing plant was in Morgantown, West Virginia, but he did not stay long. For reasons that have never been explained, he moved his operation frequently – first to Brattleboro, Vermont, then to Holyoke, Massachusetts, and then to Washington, D.C. for 15 years before finally ending up in West Palm Beach, Florida. In 1928, a hurricane destroyed his shop and shooting ground, and that was the end. He died there in 1934.

James J. Grant, who probably knew more about single-shot rifles than any authority of his time, covered Farrow’s life and work most extensively in his second book, More Single-Shot Rifles, published in 1959. In it, he reproduced Farrow Arms Co. letterhead from the Washington years, and it reveals much about Farrow and his company. They were, it states, “machinists, model-makers, inventors, manufacturers” with “repairing fire-

arms of all kinds a specialty.” They were “experts on motor-cycles and explosive engines” and solicited “work on electric devices.” Nowhere does it mention building custom rifles, or even rebarreling rifles of other makes, which was supposedly a major activity.

Although Farrow’s various rifle patents are most notable to shooters, it was another invention entirely – a coaster brake for bicycles – that appears to have been a major source of income. He sold the patent to a bicycle manufacturer that licensed its use to others, and Farrow shared in the royalties.

No doubt his company did make rifles, but not very many; most were on a custom basis, and it seems that no two were alike. First, the numbers. Ned Roberts estimated he made no more than 1,000; another writer suggested there might be “as many as a thousand.” Bob Hayley, a modern single-shot authority, believes there were actually no more than 250. Bob and single-shot specialist Lee Shaver both say they have seen no more than two or three Farrow rifles in their lifetimes. They come up for auction so rarely as to be practically nonexistent.

This is probably the reason there is serious disagreement as to the quality of the rifles and their shooting abilities. No one has seen enough of them to justify a broad judgement. While almost everyone admires the design, with comments like “the best single-shot ever made,” and the workmanship is generally conceded to be first rate. One source said they were made from the best materials available (Ned Roberts and Ken Waters, The Breechloading Single-Shot Rifle, 1987) while another – James J. Grant – quotes “men who have real experience with the Farrow” as saying the materials used were not always the best.

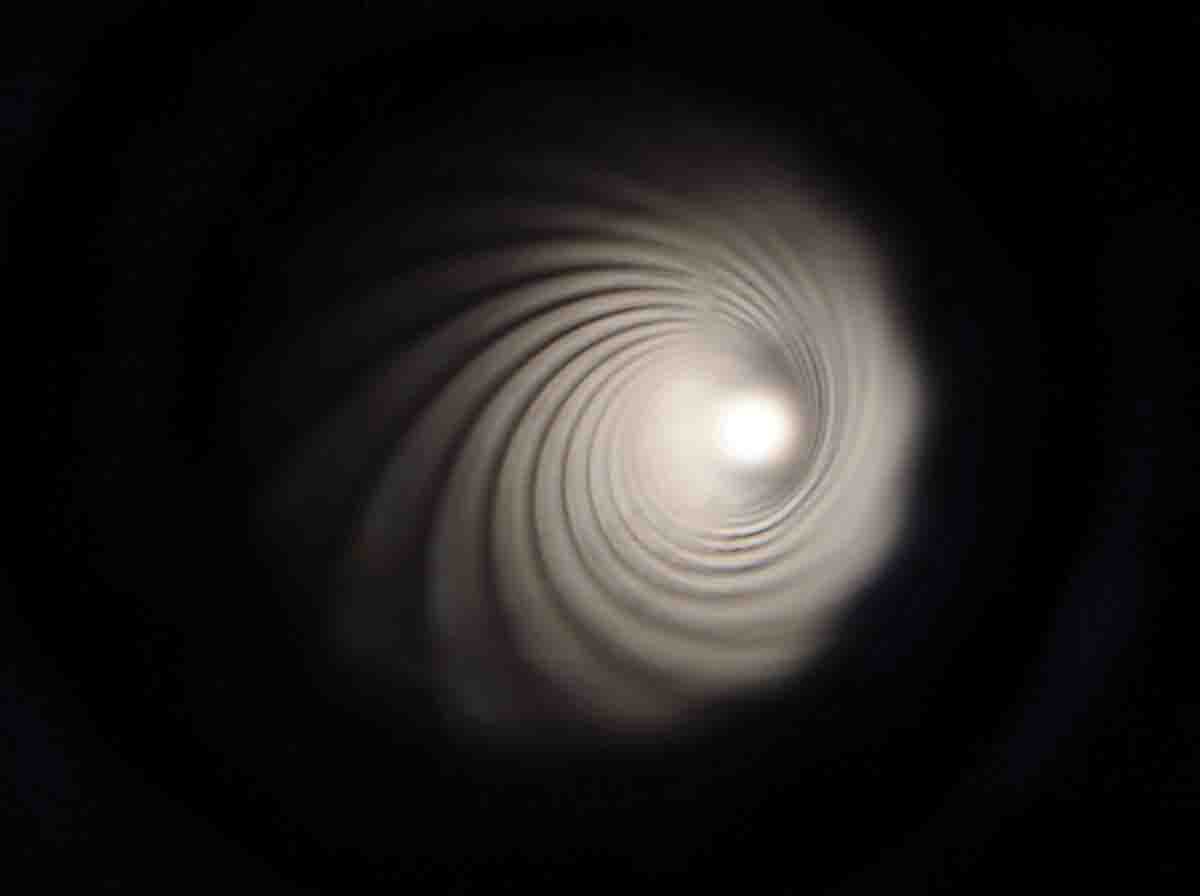

Farrow designed his rifles in the 1880s, patenting the first design in 1884, with others following in 1887 and ’88. All were slim and compact falling-block designs, with the breechblock operated by a four-finger loop lever similar to the Ballard. In one variation, the hammer is completely enclosed within the frame; in another the hammer spur extends up through the breechblock to allow manual cocking.

Its major claim to fame as a target rifle is its very short, very fast lock time. The hammer falls only 3⁄8 inch, which is remarkable. It was available with various trigger arrangements, although most seem to be fitted with a conventional non-set single trigger. Farrow’s double-set trigger was unusual in that the front (setting) trigger was placed far forward in the trigger guard and faced to the rear. It was pushed forward to set. James Grant wrote that, in his life, he saw only one such rifle.

When the breechblock is lowered, the hammer drops with it, out of the way, allowing clear access to the bore for cleaning, loading and bullet seating. It is easy to see where Farrow borrowed principles from the Ballard, then refined them to eliminate problems. In another way, his breechblock resembles the Stevens 44½, rocking forward to seat a cartridge before locking in place behind solid walls.

It would be nice to be able to say that the Farrow rifle proceeded to prove itself on the target ranges, sweeping all before it, but that never happened. If any of the best shooters used one to win a match, it’s a well-kept secret. They are mentioned nowhere in the literature that I can find, and the field continued to be ruled by Ballard, Stevens, Winchester and Remington.

Like Harry Pope, Milton Farrow believed that while some actions were certainly better than others, in a target rifle the barrel was all-important. And what counted in an accurate barrel was the design and precision of its rifling. He experimented with various rifling patterns, some having as many as 16 grooves, and a gain twist. This is also a matter of dispute. Roberts and Waters say that his six- and eight-groove barrels proved to be the best, while James Grant said the most successful and popular had 14. Again, there are just not enough of the rifles around to make a conclusive comparison. How many Farrow barrels were fitted to non-Farrow actions is a mystery, but it’s almost certainly more than on actions of his own manufacture.

After 2000, when single shots were making a comeback and everyone was talking about reintroducing the Ballard, Stevens and so on, there was no rush to make a copy of the Farrow. At the time, I asked one prospective maker why not, and he insisted the NRA rules committee for silhouette shooting would disallow it because it had a “hammerless” action. I have never been able to confirm that. One shop in South Dakota, Miller Arms, did make an action based on the Farrow, but externally it looked nothing like it, being all modern angles and sharp corners. By contrast, the Farrow is slim, compact and graceful.

James Grant knew of one copy of the Farrow rifle, which was handmade by a rifleman in Colorado, and included photographs of it in one of his books. Having handled it, he said it was slick and functioned well (although stocked in 1950s-style, which is not a compliment), but that particular rifle was unique. One wonders where it is today.

With so few rifles extant, it is difficult to make blanket statements about features and finishes, but it is generally acknowledged the Farrow was made in a “grade one” with fine walnut and checkering, and “grade two” with plainer walnut and no checkering. Some frames were blued, others were nickel-plated. Farrow himself favored the .32-40 Remington, but almost all rifles known to exist are chambered for the .32-40 Winchester (or Ballard, for the purists). I have fired the “grade one” rifle shown here, but not enough to prove or disprove much except to say it functions beautifully.

One expert who did was Ned Roberts, who watched Farrow shoot scores of 48, 49 and 50 out of 50, at distances of 500 and 600 yards, in August 1888. Roberts later had extensive use of a Farrow rifle. He reported that with his loads he was able to achieve, more than once, perfect 10-shot scores at 200 yards on the Standard American Rest target. It was, he wrote, “extremely accurate” shooting both from a rest and offhand.

Roberts’ conclusion: “Riflemen who have used the Farrow rifle at all extensively agree that it is as near the perfect single-shot target rifle as has ever been made in this country, and it is indeed unfortunate that this action, at least, is not in production now.”