Spotting Scope

Winchester Model 95 Quasquicentennial

column By: Dave Scovill | July, 20

Of the first cartridges introduced in the Model 95, two were black-powder numbers, the .40-72 and .38-72 WCFs, along with the smokeless .30 U.S. (aka .30-40). The .303 British was added in 1898, the .35 in 1903 and the .405 WCF in 1904. The .30-03 and .30-06 Springfields were added in 1905 and 1908, respectively. The Russian order for 293,818 7.64x54 muskets took two years to fill in 1916/17.

Having used all but the British and Russian cartridges that are quite similar in the smokeless lineup listed for the first generation Model 95, the .35 WCF factory load with the 250-grain roundnose slug at roughly 2,200 fps is likely one of the most useful overall, from deer and black bears to moose, for modern-day hunting, since it has been used effectively from its introduction against all North American big game.

The .405 WCF was made famous by President Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt on his 1909 African safari, and it still retains an almost mythical reputation as a big-bore hunting rifle, albeit most folks who have managed to locate a first- or second-generation rifle have complained bitterly about recoil. One can only conclude that modern writers are softer than Teddy, or the general reputation of older lever actions as somewhat weak and underpowered has been peddled by folks who have never fired a big-bore Model 86 or 95 and certainly never hunted big or potentially dangerous game with one. Then too, the first generation crescent steel buttplate was the same size and style that graced the less powerful Models 73, 92 and 94 rifles, and by any rational comparison contributes to the .405’s reputation as a “mule kicking &%$#@*.”

The logical solution to the “recoil” problem is to keep benchrest sessions to a minimum. The Model 95 is not a bench rifle and as an older gentleman once advised, “stand up and shoot it like man . . . it won’t belt you as hard if you roll with the punch.”

When the first of the second- generation U.S. Repeating Arms Company (USRAC) Model 95s were chambered for the .30-06 and .270 WCF, one of the more common talking points was that the action design (lever action) was actually too weak for such high-power, smokeless cartridges. By extension, that apparently meant a steady diet of factory loads would eventually lead to headspace problems. The culprits, as we are given to understand the logic, was bolt stretching abetted by setback of the locking lug at the lower rear of the bolt. The most interesting part of that claim, however, is that no modern testing facility has fired one rifle enough to document the phenomenon on the USRAC Model 95 or any other lever action of the same or similar design, aka Marlin 336 and/or 95. The point being, if you want to sell rifles in this day and age, don’t let the gun press get started on subjects they know nothing about, which leads to something like 3,000 USRAC Model 95 rifles sitting in a warehouse in Utah.

Of course, the other stake in the heart of the Model 95 .30-06 and .270 WCF rifles was that they were not scope friendly, which to a modern gun writer is akin to blasphemy, aka a crime against humanity.

As it turned out, I spoke with Wayne Holt at Hornady about the idea of making .405 WCF ammunition, which “might” inspire USRAC to send the 3,000 rifles back to Japan and rebarrel them to .405 WCF. Within hours, Hornady and USRAC agreed to the joint project.

When the second generation .405 WCF rifles arrived back in the Lower 48, they received all-around approval, save for the fact that they, as always, were not scope friendly. It appears to be a fiat accompli that modern gun writers, save for the Wolfe Publishing staff, are doomed to failure when it comes to the use of open sights beyond 50 yards. Even so, the supply of Hornady .405 WCF factory loads seemed to disappear from display shelves fast enough.

Since writers don’t buy factory loads for limited edition rifles like the .405 WCF that you can’t mount a scope on, it would be fair to assume the public was responsible for sweeping the ammunition supply off the shelves, not only to feed the second generation rifles, but also to put first edition rifles that had gone without ammunition since the early days of World War II back into service.

The greatest selling point of the Model 95 was that it was chambered for all of the more popular high-power cartridges of the period, starting with the .30 U.S. (.30-40 Krag). Its advantage, besides standing up under the harsh Arizona/New Mexico mountain and desert environment, was that a post-1903 Arizona Ranger so armed could remain out of range of the traditional rifle cartridges of the day of around 200 yards or so, knowing the effective range of the .30 U.S. was well over 1,000 yards. The Model 95 also proved capable of enduring the harshest of battle conditions, e.g., the taking of Kettle and San Juan Hills in Cuba and in the Philippine jungles against the Spanish Mauser.

One of the great ironies in the saga of the Model 95 is that it has been reintroduced in the second generation Browning and Winchester (USRAC) editions in .270 WCF, .30-06, .30 U.S. and .405 WCF, while one of the finest big-game hunting cartridges of the period, the .35 WCF, has been unceremoniously overlooked among the hoopla over the fabled rhino- busting .405. The lesson here is that writers knew little to nothing about the .405, save for Roosevelt’s use of it with solids, no less, or just quote John Taylor’s bashing of it, who never used one either.

According to Winchester data charts from the early 1900s, the .35 WCF would be the rimmed version of what we now know as the .35 Whelen, with a 250-grain bullet at 2,250 fps, or a bit over 2,300 in handloads, from a 24-inch barrel. The Whelen can shoot that bullet weight a bit faster, but it is still the 220-yard, open-sighted, point-blank equal of the WCF. If Roosevelt had taken a .35 WCF to Africa, he needn’t have bothered with the .405, since he had a big double rifle anyway, and used the .30-06 for plains game, leaving folks today begging Browning Arms Company (previously known as USRAC and/or Winchester) for a quasquicentennial Model 95 .35 WCF, albeit with a thick, cushy recoil pad. A fantasy for sure, but something to hope for and stop worrying about the drought in toilet paper and Corona beer. Where is Stanley Kubrick when you need him?

Since Model 95 .35 WCFs have been out of production since the 1930s, it is difficult to find ammunition and/or brass for reloading. Fortunately, there is no shortage of .35-caliber bullets that are suitable for anything from small game to moose and larger bears. The best source of brass is Bertram Brass out of Australia that is available through Huntington Die Specialties (huntingtons.com) and Buffalo Arms (buffaloarms.com), either in stock or by special order.

Prior to the availability of Bertram brass in the states, several references recommended the use of .30-40 (aka .30 U.S.) brass that forms rather easily to .35 WCF, but the neck comes out a bit short. Others have suggested extruded .30 U.S. brass that is stretched to proper length may also be prone to head separation.

Back in the 1950s, Lyman listed the .35 WCF with a 200-grain bullet seated over 48.0 grains of Hi-Vel and 50.0 grains of IMR-3031, at 2,480 and 2,400 fps, respectively. A 250-grain roundnose slug was listed with 49.0 grains of IMR-3031, 50.0 grains of IMR-4064 and 51.8 grains of IMR-4320 for 2,320, 2,190 and 2,230 fps, respectively.

In his “Pet Loads” feature, Ken Waters listed 48.0 grains of IMR-4320 with a 250-grain Speer spitzer at 2,249 fps and 45.0 grains of IMR-3031 with the same bullet at 2,232 fps, both in Bertram brass. Ken cited the 225-grain Nosler Partition seated over 48.0 grains of IMR-3031 at 2,320 fps as the best all-around load in his second generation Browning Model 95 .35 WCF with a rebored .30 U.S. barrel.

Ed Stevenson

(1930-2020)

Ed Stevenson of Sheep River Hunting Camps has passed away. He was 89 years old.

Ed was raised in Wyoming with a ranching background and served as a big-game guide, trapper and horseman. He truly loved hunting and in 1960 packed up his guns and gear and headed to Alaska “just to hunt.” He soon became a licensed guide and outfitter. While he provided hunting opportunities for moose, sheep, mountain goats, black bear, etc., his specialty and first love was the great Alaskan brown bear. In spite of his extensive experience, he was attacked and bitten several times.

Ed was a truly unique individual. For example, most Alaskan guides and outfitters head back to civilization after the hunting season is over, but not Ed. He loved the bush and stayed there year-round. He had camps (or cabins) that were strategically placed so that he could hike from one to the next in about a day. When temperatures plummeted in the Alaska Range from -30 to -50 degrees below zero (and sometimes -70 degrees below), he would make the 15-mile trek over rivers and through rugged country to the next cabin, checking his trap lines along the way. He was tough as nails and even had the grit to raise his family in the bush, where they learned respect, work ethics and character that is often missing in modern society.

I had the good fortune of hunting with Ed many times for moose, Dall’s sheep and brown bear. On my first trip, we immediately became good friends. We understood each other and “spoke the same language” when it came to guns, hunting, respect for others and our choices in life. He was also a great conversationalist and often shared humorous stories.

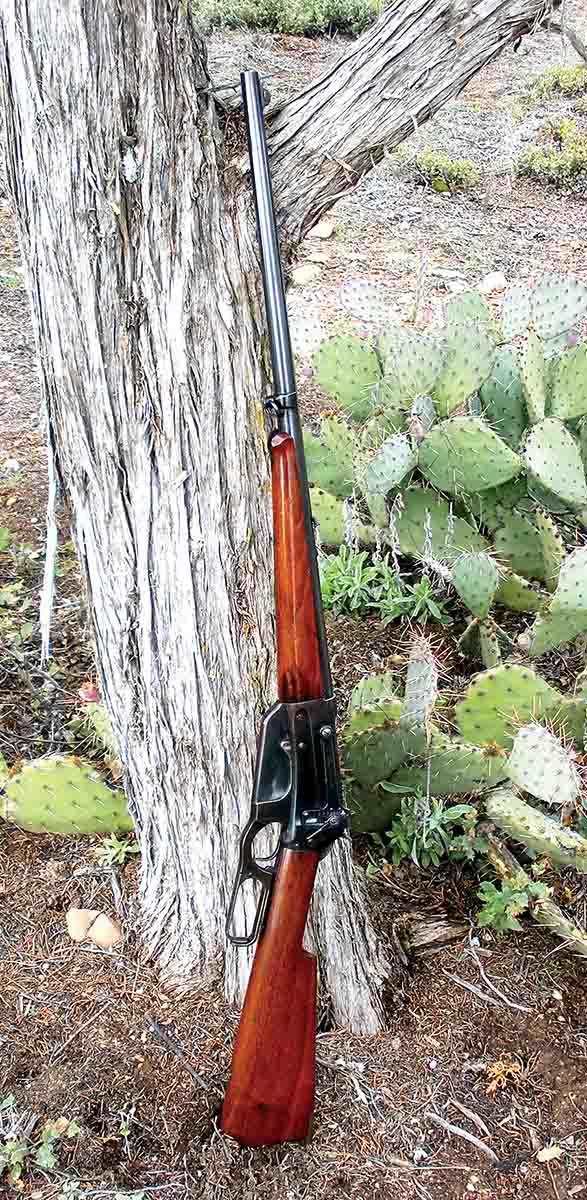

Ed used guns daily, and they literally saved his life many times. He was particularly fond of the reliability, handiness and power associated with big-bore leverguns. His favorite calibers included the .45-70 with heavy handloads, .450 Alaskan, .411 Hawk, .375 Hawk/Scovill and .348 Winchester; however, he also used a pre-’64 Winchester Model 70 with a 20-inch barrel chambered in .375 H&H Magnum for many years.

Over the years, Ed obtained three guns from me, the last one being a Marlin Model 1895 Guide Gun chambered in .45-70, which helped save his life. A couple of years back he called and related that he had been attacked by another brown bear, which came from nowhere and put him on the ground on his back. The bear was on top of Ed with his face just inches from Ed’s face. In just the nick of time, his dogs attacked, which made the bruin turn around. This placed the bear’s rear toward Ed’s face, which gave him just enough room to get the Marlin rifle in position and fire. The heavy bullet essentially penetrated lengthwise through the bear, into its vitals. Sadly, one of Ed’s dogs died in the attack.

Many years ago, in these pages I authored an article on Ed and his rifles. After publication, his daughter Debra Hartman (Stevenson) wrote to me, offering praises to her father. Using just a small excerpt from that letter she stated, “He raised my brothers and I back in Sheep River. Nobody could have picked a better place to teach the children the true value of life and living on common sense values that seem to be lost in the world today. . . . I owe my Dad more than I could ever say for the education he endowed us with. I know that your story was about the guns that Dad carried, but I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to tell you about the personal experience with The Legend of Sheep River.” I too consider myself lucky to have known Ed. He is deeply missed.

Sheep River Hunting Camps will continue to operate under the direction of Ed’s son Ben Stevenson, who is a very capable pilot, guide and outfitter.

– Brian Pearce